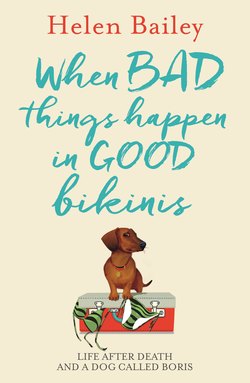

Читать книгу When Bad Things Happen in Good Bikinis - Helen Bailey - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

LONELINESS AND THE LATE NIGHT GARAGE

ОглавлениеOur world has been smashed into millions of tiny shards and that is extremely disorientating. I didn’t return home for months after Phil died suddenly, and before I did come back, my parents had to redecorate and box up Phil’s things for me. The razor on the sink, shoes on the mat, laundry in the basket and coat on the hook eviscerated my soul to the point of screaming madness. I returned once, to choose the clothes we were burying him in. That was and will always be the hardest thing I will ever do. The colossal weight of the grief, shock, loss was so immense as I took out some carefully folded underwear and his favourite well-worn jeans, I really thought it might kill me. ~ Sam

One evening, a long time ago (two decades) in a land far away (Northumberland), my best friend’s father jumped up to answer the phone and died of a heart attack. I’d come across death before, but only in the old or very ill. Mr P was fun, feisty and barely into his fifties, a larger-than-life character whom I adored; it seemed impossible that he was here one minute and gone the next.

During a trip home, I visited his widow. ‘What have you been doing?’ I enquired with all the finesse of a young elephant. Much to my surprise, instead of sobbing, ‘Nothing,’ whilst clutching a tissue and swigging Harvey’s Bristol Cream straight from the bottle, Mrs P gave me a run down of what she had been up to: going here, going there, doing this, doing that; a veritable social whirl.

‘It’s great you’re going out!’ I trilled, relieved that she appeared to be getting over her husband’s death so quickly.

Even before JS died, I still remember the bleak look in her eyes and the bitter edge in her voice as she said, ‘Oh, it’s not the going out that’s the problem – it’s the coming in.’

Now, with painful clarity, I understand what she meant.

Explaining to a friend the searing loneliness of coming in through the front gate to the front door after an evening out, he suggested I used the garage door as part of trying to establish a ‘new normal’. I’ll try anything other than potholing once, so one night as the minicab drove off before I even had my key in the lock of the gate, I decide to give it a go.

I press the ‘dibber’ on my key ring, and in the deserted street, wait for the garage door to chug open. It occurs to me that if someone wants to mug me, now would be an ideal time. ‘Bring it on!’ I think defiantly, imagining myself overpowering any mugger who dares to even glance at my wedding rings. I feel bolshy, ballsy: I’ve been out! I’m coming in! I’m establishing a new routine and I’m not crumbling in a heap of tears and yelling into the silence at the unfairness of it all! I can do this!

The garage door opens, and the security light flicks on, illuminating the interior with harsh cold light.

Any hint of bravado I was feeling drains away.

I’m like a rabbit caught in the glare of car headlights, trapped and transfixed in horror by the scene spread out before me.

Right by the door are my husband’s golf clubs with their furry animal covers. Next to them, his bike jostles for space with his golf trolley. I spot the bit of carpet he’d stuck on the wall to stop me scraping my car door on the concrete; I must have seen it hundreds of times, but only now do I appreciate his kindness. His Black and Decker workmate is folded up against the wall. There’s tins of paint and wood stain and preserver and battered old jars and packets for jobs around the house, which only he did, and which I know nothing about. Gardening equipment hangs neatly around the walls. There are bits of wood which JS always kept ‘just in case’, wood he’d now never use. I feel overwhelmingly sad at seeing his golf shoes sitting on a shelf, just where he left them after his last game.

Tears sting my eyes and I look up to stop them falling. Hanging across the roof is a black plastic package. It looks like a small wrapped body, but it’s the fake Christmas tree we put up in the kitchen; alongside it, the stand for the giant real Christmas tree we always have in the front room. My heart breaks at the thought of Christmases past and those yet to come without him. And then there are the ladders: folding, extending, step. There are so many questions I long to ask my husband, but right now, ‘What’s with all the ladders, JS?’ is first on the list.

I press the switch on the wall and the garage door shuts. I sidle past my car to the side door whilst realising I’m not alone: every giant spider in north London is partying around me.

I unlock the door to the garden and closing it behind me, pick my way through an orgy of slugs.

Finally, I get to the front door. The Hound is on full alert having heard the garage open, and he greets me with noisy excitement. It’s lovely to see him, but we missed the class at Puppy School where they taught him how to flick the kettle on. He has lots to say, but even if I could translate his barks, I doubt he’d be asking, ‘How was your evening?’

I decide that I won’t come in through the garage again, but it doesn’t matter anymore because I’ve solved the problem of coming in at night.

I no longer go out.