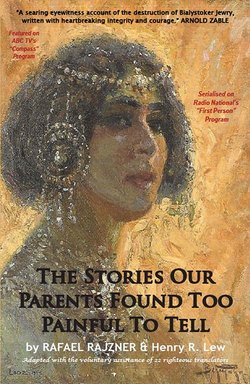

Читать книгу The Stories Our Parents Found Too Painful To Tell - Henry R Lew - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 2.

ОглавлениеTHE SOVIET ARMY MARCHES INTO BIALYSTOK.

Large numbers of Soviet troops started arriving in Bialystok on the afternoon of Yom Kippur eve. Townsfolk massed in the streets in order to greet them. Everybody was present, individuals, professional groups, political organisations. The mood was warm, friendly and enthusiastic. Red flags were waved, flowers were abundant. Large numbers of Jewish youth decided to boycott the “Kol Nidrei” service. They could not bear to drag themselves away from their liberators. The Soviet troops likewise responded cordially. They told of good conditions back home. “Only in the Soviet Union could all people live out their lives as free citizens.”

The next morning the Soviet Command cancelled the special conditions that had been imposed by the German Army. The city started to breathe easier. Normal life with its characteristic hustle and bustle started again. But all did not remain rosy!

The Soviet occupation brought new economic and social values with it. This made life harder, not easier, for most Bialystokers. Winter was on its way and many necessities were in short supply.

Queueing for bread was introduced. Hungry Bialystokers would stand in freezing frosts of -30 degrees Celsius from 2a.m. onwards, for 24 hours. When they finally reached the shop front they would learn that everything had been sold. Life had become very hard.

Initially there was also much unemployment, but before long, the Soviets established numerous government agencies and enlarged the factories. Several months later, by the beginning of Spring 1940, lack of employment had ceased to be an issue.

BIALYSTOKERS AND REFUGEES ARE SENT INTO DARKEST RUSSIA.

With near full employment life began to normalise. Food supplies improved. Bit by bit people adapted to the new way of life. Conditions became more bearable.

That first winter housing was a significant problem. Factories had been enlarged in preference to building dwellings. Thousands of Soviet officials had arrived from greater Russia to commandeer a substantial number of existing dwellings, and tens of thousands of Jewish refugees had poured into Bialystok from the west, mainly from Warsaw and Lodz. These men, women and children had walked hundreds of kilometres, in ferocious weather, to escape the hell which the Hitlerites had created. They surreptitiously and illegally slipped across the border into Soviet territory. Bialystok, a city of 100,000 people before the war, more than doubled its population. Private housing became grossly overcrowded. The overflow had to be accommodated in synagogues, in houses of study, and in community centres. Conditions became poor and hygiene suffered.

Bialystoker Jewry did their best for the refugees. Those who could be accommodated in private homes were. But under the Soviets, the Bialystokers were no longer masters of their own homes. People had been forced to downsize their living space and many apartments no longer had room for new inhabitants.

Many of these Jewish refugees had been people of means before the war, and they found the current miserable conditions unbearable. Some even returned home to the west, failing to strike an appropriate balance between the threat of death in the Soviet versus the Nazi sector.

The Soviet authorities did not want the Jewish refugees to remain in Bialystok. Their policy was to drive them deeper into Russia. The Soviet security forces started serving the refugees with permits, which required they translocate themselves to the eastern side of the old Polish-Russian border. However, the majority of the refugees seemed keen to remain in Bialystok and showed no signs of moving on. For a little while the Soviets tolerated this.

Then, one appointed night, late in April 1940, the NKVD secret police pounced. They surrounded the buildings where most of the refugees were housed, conducted mass arrests, transported prisoners to the railway station, and loaded them onto freight cars. But these refugees were not alone. A few thousand Jewish and gentile Bialystokers were transported with them. These townsfolk were “the undesirables,” capitalists not communists, and included in their number were factory owners and prominent merchants. All of these people were sent to the farthest reaches of the Soviet Union. At the time their deportation was deemed tragic, but in reality many of them survived because of it.

These events impacted strongly on the majority of Bialystokers. They worried about the fate of the deportees. Everyone wondered whether he or she would be next. Several months later people started receiving letters from the deportees. They complained that they were starving and begged for food rations. The Bialystokers responded strongly to their requests and, thanks to the many food parcels sent, the situation of the deportees improved.

NORMALISATION OF LIFE IN BIALYSTOK.

With the passage of time life in Bialystok began to normalise. Established factories were working two to three shifts a day. New ones were being built. New state-owned shops opened daily and people could soon buy enough to satisfy their basic needs.

Social institutions prospered under the Soviets. Elderly residents of the Jewish poorhouse and the Jewish old people’s home were generously provided for. Initially they even managed to retain their kosher kitchen. However later on it was decided to merge these Jewish institutions with Christian ones, and their inhabitants were moved to newer cleaner premises in Suprasl. These arrangements were not to the liking of many of the elderly Jews. They had lost their kosher kitchen and they felt uncomfortable living intimately with gentiles. Those who were strictly orthodox felt a need to leave.

The three Bialystoker orphanages were similarly amalgamated into a single institution, under the directorship of Simon Brodie. They were relocated into a large handsome building on Wesola Street. The children enjoyed the best of everything under the Soviets. They were given plenty to eat and they were well dressed.

The Soviets also accomplished much in the field of education. Because of the excessive numbers of students, existing schools worked two to three shifts a day and plans were drawn up for the building of new schools.

Cultural life in Bialystok continued on a high level. Well-known Polish, Russian and Jewish theatre companies visited the town. Abraham Morevskin established a Jewish National Theatre. Moshe Broderzon, a poet, writer and playwright from Lodz, opened a Jewish Miniature Theatre. The Yiddish comedians Shimon Dzigan and Israel Schumacher were its star attractions. A city choir was founded. The well-known Warsaw chorister Mr. M. Schnayur was appointed as its director. Eddie Rosner brought his famous Warsaw jazz orchestra to Bialystok. A community folk house was opened to encourage people to engage in such activities as theatre, music, singing and painting. Large factories formed their own musical ensembles and professional artists were engaged to manage them. The city’s cinema houses were expanded. Prices were affordable and these venues were always playing to packed houses.

It was at this time that the two famous Jewish artists Landoy and Zishe Katz died.

Landoy was performing Shakespeare’s “The Tempest” to a packed Palace Theatre. All of a sudden he suffered a heart attack and dropped dead. The impact was overwhelming. The performance was cancelled, but Landoy’s dead body continued to lie on stage. The next morning the artists’ union issued an obituary notice to the effect that Landoy’s body would lie in state on the stage for the entire day. His fellow artists would form a guard of honour by his casket, and theatregoers who admired him were invited to come and pay their last respects. A huge crowd attended his funeral and after it the theatre closed for several days as an act of respect.

Katz was suffering from depression because some of his closest friends had been deported to the farthest reaches of Russia. In a moment of extreme grief he penned a suicide note and hanged himself with a pair of suspenders. His death had a profound effect on people in artistic circles.

Both men were buried in the Bagnowka Cemetery.

THE SOVIET AUTHORITY’S ATTITUDE TO JEWISH

RELIGIOUS NEEDS IN BIALYSTOK.

The Soviets made no attempt to cater for Jewish religious needs. Nearly every Jew in Bialystok was now a public servant, working either for a government factory or a government instrumentality. All workers were required to start work early, while it was still dark, even on the Sabbath.

There was little opportunity to attend organised early morning prayers, a situation compounded by the fact that most Jewish prayer houses had been commandeered for other purposes. They were being used as military quarters, sports clubs, granaries and store houses.

Jewish religious institutions were heavily taxed and none more than the Great Synagogue. Its land tax bill was five roubles per square metre, which amounted to 4000 roubles per month. All religious institutions were made to pay five roubles per kilowatt hour for electricity, nearly fifteen times the normal rate of 35 kopecks. This forced the few prayer houses which remained open to be very frugal with their lighting, even on important holy days. This high cost of lighting was a deliberate Soviet ploy. It was designed to trivialise the importance of these institutions and to demoralise their membership.

A religious Jewish carpentry co-operative was established. Its members were not required to work on the Sabbath or on Jewish holidays. Some of them slaughtered their own meat to ensure it was kosher. They were happy to supply kosher meat and other religious priorities to strictly observant Jewish families.

The Mikveh, the Jewish ritual bath-house, where religious Jews and their wives immersed and purified themselves, was also commandeered by the state. The members of the religious Jewish carpentry co-operative responded by collecting money for a new Mikveh. They re-built it inside a private dwelling. It was very popular. Many people came and visited, from nearby and faraway.

Some very religious Jews refused jobs where they had to work on the Sabbath. Skilled tradesmen, capable of earning 600 roubles a month, took lesser jobs, at 130 roubles a month, as security guards or night watchmen. If one walked past locked shops, in the early hours of the morning, they could be seen wearing prayer shawls and phylacteries and praying with devotion. It was a heart-rending sight.

THE FEAR THAT NAZI GERMANY WOULD ATTACK THE SOVIET UNION.

The winter of 1940-1941 ushered in a return to a more or less normal life. Then rumours began circulating regarding a war with Germany. By early summer these rumours started to acquire some substance. Large convoys of Soviet military transports were seen driving westwards through Bialystok towards the German border.

The threat of war caused the Soviets to act against people who they saw as possible fifth columnists. Early on Thursday morning June 19th 1941 the Soviet police swooped. They raided many homes, Jewish and non-Jewish, looking for people who had been politically active during the previous Polish regime (1919-1939). This included Zionists, Bundists, Revisionists, clergy of all denominations, prominent businessmen, wealthy landowners, indeed anyone who could have been interpreted as being anti-Soviet. The men were arrested and imprisoned. The women and children were trucked to the railway station and loaded onto freight trains destined for the farthest reaches of the Soviet Union. Chance had it that many of the women and children survived. The men were not so lucky. When the Germans arrived a week later they were released from prison. Those who were Jews were eventually gassed and incinerated with their fellow Bialystokers.

The cruelty of the Soviet police generated fear and terror among the townsfolk. But its duration was short lived. Two days later war broke out and what followed was so gruesome that Soviet atrocities were soon forgotten.