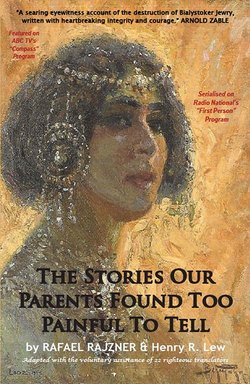

Читать книгу The Stories Our Parents Found Too Painful To Tell - Henry R Lew - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3. FRUITION

ОглавлениеThe real breakthrough came one day when my wife Sandra asked me to take her shopping to the supermarket. “Do I have to?” I replied. Her response was, “Be a friend and keep me company. While I’m shopping I don’t mind if you go across the road to the Sunflower Bookshop.” The Sunflower Bookshop specialises in books of Jewish interest.

While I was in the bookshop I picked up a volume entitled “Outwitting History” by Aaron Lansky. It was subtitled “How a Young Man Rescued a Million Books and Saved a Vanishing Civilisation.” This book grabbed me from its very first page. I strongly recommend it to anyone who wishes to experience an incredible read. By the time Sandra came to collect me I had already devoured a number of its fascinating pages.

It told the story of Aaron Lansky, an eighteen-year-old, first year student at Hampshire College Massachusetts who, in 1973, enrolled in a course of “Holocaust Studies.” He came from a secular Jewish family and had never heard Yiddish spoken at home.

Within a short time, Lansky was becoming less interested in the Holocaust as an event, and progressively more interested in the people whom the Holocaust had sought to destroy. He transferred his interest to what he calls ‘a sociological viewpoint of Jewish History,’ a fascination not with Judaism but with Jews. And it soon became obvious to him, that if he wished to continue to pursue his journey, he needed to seek out original source material. And to do this he needed to learn the language in which this source material was written. He needed to enrol in a course to study Yiddish.

One thing led to another and Lansky started to look for Yiddish books to help him improve his language skills. He soon became aware that many older Yiddish speakers were dying and that their extensive Yiddish libraries were being thrown out into dumpsters and being buried in ground-fills. If these procedures were allowed to continue Yiddish would gradually die out and eventually become extinct. This realisation transformed Lansky’s life. It caused him to stop his formal Yiddish studies and to become, instead, the man he is today, the man who has devoted the rest of his working life to the rescue of Yiddish books.

Lansky now started to lay the groundwork for what eventually became the “National Yiddish Book Centre.” This centre would serve as a storage point for the collection of unwanted Yiddish books. If asked the centre was happy to distribute any duplicate copies of its books to anywhere in the world, wherever individuals or institutions, such as schools or universities, might happen to want them. To facilitate all of this Lansky mobilised a small army of friends and acquaintances who were willing to help. He started to write many letters to prominent Jews, to writers and intellectuals, to leaders of the American Jewish community, and to numerous Jewish agencies, seeking support. He was looking for funding and, as is usually the case, it was proving difficult to find. It is certain that his dream would never have survived, except for the generosity of a small number of early interested benefactors. Lansky, however, was a man of perseverance and before long he had convened a board and managed to find six thousand square feet of floor space, the whole second floor of an old dilapidated warehouse, at a modest rental of nine thousand dollars per annum.

Lansky also issued press releases to more than three hundred newspapers. Newspaper publicity followed and people started to develop an awareness of the book centre’s existence. Articles appeared in the Boston Globe, the New York Times, numerous Jewish publications, and eventually even in Time Magazine. All this media attention stimulated more and more Yiddish readers to offer their libraries to the centre or to volunteer as active “zamlers” (local district collectors) for the centre. Lansky became an invited speaker and was asked to make television appearances, on one occasion together with Leo Rosten, the best selling author of “The Joys of Yiddish.” After the fall of communism he delivered Yiddish books in person to Russia. He was granted a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship, worth nearly a quarter of a million dollars, and received an offer to relocate his National Yiddish Book Centre, free of charge, to the Mount Holyoke College Campus in New England. Instead he decided to purchase a block of land adjacent to his former alma mater, Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts. He saw the independent purchase of property as the only means of providing the centre with permanence. A $7,000,000 institution was designed to be built on the block. In appearance this building was to be based on the old wooden synagogues of eastern Poland and Russia. More appeals were held, but now that Lansky was well-known the funds were eventually raised.

Today the National Yiddish Book Centre is one of the foremost and best known Jewish institutions in the United States. And all this is due to the whim of a dedicated penniless persistent young idealist, truly an example of a miracle in our own times.

I bought “Outwitting History,” took it home, and devoured it in forty eight hours. It was inspirational. I immediately e-mailed Aaron Lansky and asked him if he could supply me with a list of names of Yiddish translators. He sent me fifty-nine names. I wrote this letter to each and every one of them:-

Dear Sir/Madam,

My name is Harry Lew and I am writing to you with a most unusual request. There is a book published in Yiddish, in Melbourne in 1948, by a Holocaust survivor Rafael Rajzner titled “The Annihilation of Bialystoker Jewry.” I want to get this book translated into English, to make it available to a wider audience. I am therefore writing to everyone on the National Yiddish Book Centre’s register of prominent Yiddish translators asking for a mitzvah (good deed). If I send you ten pages of this book would you be kind enough to translate it into English for me.

When the whole book is translated I will edit and publish it, mention each contributor, and send each contributor a personal copy to donate to the Holocaust Museum or Library of his or her choice. Please reply to this letter and tell me if you can help me.

Yours sincerely,

Harry Lew.

I also approached some local people. Rajzner’s book contained three hundred and twenty-four pages. I needed thirty-three translators.

I got less than the thirty-three required takers, but at least we had a start. A number of the translators wrote back to say that they would be pleased to do the work for a fee, usually in the vicinity of $US 500, but these people were rejected. This book would be translated gratis by 22 “Righteous Human Beings” who gave of their hearts. The English translations varied considerably, but this was to be expected. Some of them required more work, others less, but they were equally appreciated. My job was to try to give them a single voice, to try to create the feeling that the translations had been done by a single person. It is left to the translators themselves and to my readers to tell me if I have been successful. I will gladly accept their verdict whatever it may be.

To give this book a single voice was not an easy task. Rajzner, himself, is quite variable. Some parts of his book read like a best selling thriller, other parts are quite parochial. He mentions many people by name, who would not normally be considered to be historically significant, the sort of people who might not be mentioned anywhere else. Rajzner might be the only surviving record of their existence. I am reminded of the numerous foot soldiers who gave their lives for a cause, only to be forgotten forever. Generals tend to be remembered by history, not the nameless privates who do the brunt of the dirty work.

I therefore decided against deleting any of the names. I wanted everyone mentioned in the Yiddish text to appear in the English one. I even added a few more, my grandparents Hersz and Raya Leah Lew; my uncles Fishel Lew and Hillek Basz; and my cousin David Lew; about whose fate Rajzner had informed both my parents way back in 1947. I made no attempt to upgrade Rajzner’s language, to transform it into high literature. For one I am not the person sufficiently talented to do so. I am neither a poet nor a man of letters. My aim has been simply to re-create this book in English as Rajzner originally intended it to be, a frank eye-witness account of a terrible human tragedy.

Some of my 22 translators, on completing their pieces, volunteered to do more. I always accepted their offers. In some instances it enabled me to get the same pages translated twice. I found these dual translations particularly helpful. At other times when I experienced difficulties turned to Mr. Israel Kipen, a fellow Melbournian and a former Bialystoker, for help. Israel was one of my translators and nobody could have been more obliging. He is a wonderful man, a gentleman and a scholar, who was at all times ready and willing to offer me help.

And then one day, lo and behold, the whole book was translated.