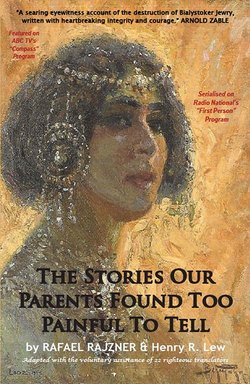

Читать книгу The Stories Our Parents Found Too Painful To Tell - Henry R Lew - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2. CONCEPTION.

ОглавлениеI remember, many years ago, hearing someone make the comment that writing a book is like having a child. From the perspective of a parent, I cannot bring myself to agree with this. For a parent every child nurtured is irreplaceable, a book like any other work of art is not. It can be re-done. Yet for some inexplicable reason this statement remains fixed in my mind. It was explained to me at the time that a writer is inspired to create a book by an act of love. The manuscript grows out of nothing into a form with a future. It is cared for along the way, emotionally and financially, by its creator. And finally it develops an independent life and propels itself into the future.

With all this in mind I can clearly remember the evening that this English version of Rafael Rajzner’s “The Annihilation of Bialystoker Jewry” was conceived. It was during the summer of 2001-2002. I was driving home from work and, as was often the case, I decided to look in on my elderly father. He was in his ninety-fifth year and not particularly well. I let myself into the house. I always carried a key from that day thirty years earlier when I first left home. I walked the entire length of the building for the kitchen, in which he was most often located, was at its rear. Lonek was sitting at the table, as usual, reading his newspaper. He looked up at me and smiled. His eyes always radiated a genuine pleasure whenever he saw me. “Sit down Harry,” he beckoned, “and share a cup of tea with me.” He always wanted to share something with me. “I wanted to ask you whether we had ever discussed Rafael Rajzner’s book?” We hadn’t! “I picked it up today,” he continued, “and re-read some of its pages. I hadn’t done this for more than fifty years. Rajzner tells us the story about how Jewish Bialystok was destroyed. I knew Rajzner well from the Bialystoker Centre. I bought the book directly from him, when the Bialystoker Centre published it, in a small Yiddish edition, in 1948. It is an extremely valuable book. This is not because Rajzner was a writer, an intellectual or a historian. He was none of these things. In fact he was quite a simple man and he wrote in a rather simple Yiddish. He does not analyse and discuss or offer opinions and explanations. The real importance of his book lies in the fact that he was a survivor of the ghetto; he was there; he was an eyewitness. That is why his book is so important and deserves to be preserved. No academic or historian can ever hope to compete with him, no matter who they are. It was Rajzner who told me how most of the members of my own family perished. If it were not for him I probably would never have found out. This book needs to be published in an English edition to allow it to be brought to a new and wider audience. There are many details mentioned in this book that should not be allowed to disappear, particularly in this new era of Holocaust deniers. This could well happen if such books are never translated into English. It is probably the first ethnic book about the Holocaust to be published in Australia, at a time when Australians were little interested in ethnic writings. In today’s multicultural Australian society people deserve the opportunity to access it, if not for any other reason that Bialystokers and their descendants, although small in numbers, have contributed more than their fair share to the post-war development of this wonderful country.”

“You would have been the ideal man to translate this book,” I told him. “Your Yiddish is excellent as is your English, and you have been retired for nearly thirty years.” But as I looked into his eyes I was suddenly aware of a profound sadness entering them. He nodded his head from side to side. “Unfortunately this was never a job for me,” he sighed. He became silent for a while and then he moved on to other matters. I always knew that Lonek could have translated a Yiddish book like Rajzner’s effortlessly, as easy as pie. The language would never have been an issue. It was the contents that was the problem, a nightmare for him, and simply too painful to dwell on. It dealt with the destruction of the centre of his universe. Lonek’s method of coping had always been to put such issues aside as best as possible, and to concentrate, instead, on the rest of his life. And he did this admirably, even to the extent of repeatedly saying there are no evil nations only evil people, and that the good people of all nations deserve his respect.

I feel a need at this point to make special mention of the “Bialystoker Centre.” A significant number of Bialystoker Jews had migrated to Melbourne during the nineteen twenties and thirties in search of a better life. Many of them became highly successful businessmen and prospered. Leslie Rubinstein, Michael Pitt and Leo Fink readily come to mind, but there were many more. When World War II finally ended a group of these Bialystokers combined resources and founded the Bialystoker Centre. The Committee included such names as Michael Pitt, Abrasha Zbar, Abraham Sokol, Misha Merkel, Judel Slonim, Abram Serry and Wolf Davis, all well known to me as a child. Others, who I don’t remember, include Messrs. Lapin, Hamery, Glagowsky, Gibgot, Silver and Dorevitch. These gentlemen purchased a beautiful Italianate mansion on Robe Street St. Kilda and made it their centre’s headquarters. When refugees such as my parents, Leo and Eugenia Lew, arrived in Melbourne in 1947 they were met with at Spencer Street Station and taken straight to the Bialystoker Centre, where free accommodation was available. I was born whilst my parents were still resident at the centre, and I was a baby there when the centre first published Rafael Rajzner’s book. It was all this nostalgia which sparked my positive feelings for the creation and publication of an English version of Rafael Rajzner’s book.

I am sure that my father would never have expected me to have been involved in the production of an English edition of Rajzner’s book. It simply would never have occurred to him. He knew that my Yiddish was limited and that in my wildest dreams I could never have translated a Yiddish book. Indeed during the few remaining months left to him, we never again broached the subject of Rajzner’s book. It was not until after Lonek’s death that I began to ponder the feasability of re-editing Rajzner’s book in English.

I was in my father’s house sorting through his library, when I suddenly came across it. It was one of a number of foreign language volumes, written in the numerous foreign languages, which Lonek both read and wrote. I managed to find new homes for most of them. Some went to the Makor Library, some to the Kadimah Library. Others were placed with organisations, which collected foreign language books and distributed them to new immigrants. However Rajzner’s book became one of a select group, and was added to my own library.

At first I looked for a suitable Yiddish translator. I made enquiries and even went as far as getting a reasonable quote of $12,000 for the job. I also thought about how to finance it. I could either pay for it myself, or I could try to raise the money in pledges, of $500 each, from twenty-four surviving Bialystokers. I gave some thought to both these options, but in the end neither seemed suitable. So like my father, I pushed all thoughts of Rajzner’s book to one side, and simply got on with the rest of my life.

I dropped the idea of employing a single proficient translator, expert in both Yiddish and English, because I didn’t want to limit myself to being a financial backer of the project. Now please don’t get me wrong. I am in no way belittling the role of philanthropists. Philanthropists play an important part in the lives of many people, much more than I could ever hope to play. But I believe that philanthropy is better spent on the living than the dead, and in this instance I felt a need to put my own sweat and tears into the project, not just my money! Also when it comes to raising funds, I have never felt comfortable asking others for money for such an intensely personal project, a tribute to the dying wishes of my father.