Читать книгу Roaring Girls - Holly Kyte - Страница 13

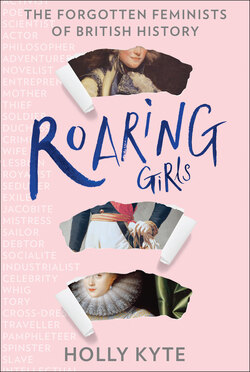

THE THREE FACES OF MARY

ОглавлениеWhen Mary Frith completed her act of penance at St Paul’s Cross in 1612, her name – or at least that of her alter ego, ‘Moll Cutpurse’ – had been on the lips of most Jacobean Londoners for several years, especially those who frequented the playhouses, taverns, brothels and bear pits of Bankside, the lawless entertainment district of Southwark that lay conveniently outside the City’s jurisdiction. Whether they loved or loathed her, feared or admired her, Mary’s notorious career as a cross-dressing thief (or ‘cutpurse’[2]) and street entertainer had fascinated the public, and by the time she’d reached her mid-twenties, she had achieved cult celebrity status – so much so that several playwrights had already appropriated, refashioned and immortalised her persona as a wholly unconventional folk heroine.

Fifty years later, Mary’s legend as one of the most enjoyably outrageous and controversial women of the age was still going strong, confirmed by the arrival in 1662 of a sensationalised ‘autobiography’, The Life and Death of Mrs Mary Frith, which, if it were what it pretends to be – the candid deathbed diary of a repentant sinner – would constitute an invaluable primary source for Mary’s life and an important early example of life writing by an Englishwoman. As it is, the diary is almost certainly a fake. There is no credible evidence that Mary wrote it herself; after all, she’d been dead for three years before it appeared, and although up to 50 per cent of women in London were literate by the late seventeenth century (a much higher proportion than in most parts of the country), it’s unlikely that a woman of low birth such as Mary would have been one of them.[3]

The book’s numerous factual errors and omissions point instead to another hand, and given its erratic style, maybe even several. Falling into three distinct and sometimes contradictory sections – an opening address, an introduction summarising Mary’s upbringing and a ‘diary’ of her life as a cutpurse – it comprises a string of unapologetic, entertaining, though often disjointed, anecdotes of her misdeeds, and seems to have more in common with the fictionalised criminal biographies that were popular at the time than it does with a genuine diary,[4] veering in tone from comic to defiant to political and even preachy.

This ‘diary’, then, is an unreliable account of Mary’s life, though that’s not to say it’s worthless. Plenty of the details within its pages chime with what we know to be true. It’s plausible that the authors had their anecdotes either directly from Mary when she was alive – an old woman entertaining anyone in the alehouse who would listen with tales of her outrageous youth – or from those who knew her, or, more likely, that they adapted them from the tales of her exploits that had been passed from gossip to gossip for decades. Mary had already written herself into London’s folklore with her riotous escapades, leaving the diary’s anonymous authors the task of matching, if not surpassing, these outlandish oral tales.

But herein lies the problem with Mary Frith. With the historical records frustratingly reticent on her real life (her appearances in them are few, though always revealing), much of what we know – or think we know – of her comes from the various fictionalised versions that appeared over the years, making her as slippery a character in death as she was in life. The legend who features in the ‘diary’, the character who walked the stage and the flesh-and-blood woman who left an imprint on the records don’t always agree, splitting her image into hazy triplicate. The diarists were aware of the issue. Their excuse for the ‘abruptness and discontinuance’ of their story is that ‘it was impossible to make one piece of so various a subject’.[5] This isn’t just an unwitting admission of their own fudged documentation of her life; evidently Mary’s baffling complexity made her as intangible to her contemporaries as she is to us.

Lower-class, lawless, unconventional and disobedient, Mary Frith was disturbing – but also strangely alluring; she represented an unusual kind of woman in the seventeenth century, one to whom society had no answer. By definition, such women lived a precarious life and needed cunning strategies to survive, and in Mary’s case that meant barricading herself in behind a protective wall of myth and mystique, cultivating multiple personalities and perfecting her performance of each one until the real woman became as elusive as wisps of smoke. With so many Marys before us, it’s as if she’s laid down a challenge: to find the real Mary Frith, and catch her if we can.