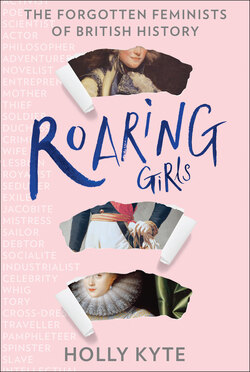

Читать книгу Roaring Girls - Holly Kyte - Страница 19

FEME COVERT

ОглавлениеThe Life and Death of Mrs Mary Frith roams freely through Mary’s career as a thief, broker and professional provocateur, but there is one significant event in her personal life that it entirely neglects to mention. On 23 March 1614, when she was still in her late twenties and just starting out as a fence, Mary Frith did something wholly unexpected: she went to St Saviour’s Church in Southwark (now Southwark Cathedral) and married a man named Lewknor Markham.[53]

This staggering omission isn’t the first or only clanger to muddy the integrity of Mary’s ‘diary’ – The Roaring Girl is also not mentioned and there is a thorny discrepancy over her age[54] – yet in this instance, it’s easy to see why it might have been left out. For a woman who defied convention and resisted authority at every turn, and who, according to legend, was resolutely single and had no interest in men, marriage seems a particularly odd choice. This inconvenient detail simply didn’t fit with the image of Mary that was being cultivated in the public consciousness; it disproved all the theories that she was an unnatural man-woman whom no man would ever marry, or a scorned woman who spurned all men, as the diary variously portrays her.[55] It didn’t fit, either, with the Moll of the play, who was ‘too headstrong to obey’ a husband and had ‘no humour to marry’.[56] For here she was, conforming to all the social conventions and acting like a perfectly ‘normal’ woman.

The records shed only a glimmer of light on the real story behind Mary’s marriage to Markham, but it’s enough to reveal that this was almost certainly no sweeping love story and that, as we might expect, Mary was not being quite the conventional good woman here that she at first appears to be.

On the contrary, Mary went out of her way to confuse the world about her marital status. Her primary motive for marriage seems to have been to manipulate the gender discriminations of coverture under English Common Law to maximise her freedoms, so that she could run her own business as a single woman, while at the same time claiming the legal immunity of a married one. Coverture laws decreed that when a man and woman married, they quite literally became one. In legal terms, at that moment a woman became a feme covert and her legal existence as an individual was nullified: she could no longer hold her own property or money, nor could she sign contracts or be sued in her own right. If she remained single, however, she retained these scraps of legal rights and was referred to as feme sole. Rather than submit to the disempowerment that these laws entailed for women, Mary decided to play the law for a fool. She became an expert at exploiting its loopholes, by posing as two different women – Mary Frith, feme sole, and Mary Markham, feme covert – as and when it suited her.

As a newly established businesswoman, for example, it suited her to be single. That same year, 1614, was when Mary set up her lucrative and semi-respectable ‘lost property office’, and for that she needed her legal independence. In order to have her cake and eat it, Mary seems to have negotiated a marriage settlement of convenience with Lewknor Markham, which allowed her to run her own business and retain her own earnings, despite being married, as if she were Mary Frith, feme sole.[57]

As a woman who flirted with crime on a daily basis, however, being Mrs Markham, feme covert and legal non-entity, could be extremely helpful. It meant that in the various lawsuits she was frequently embroiled in, she was virtually invincible, because the law would always assume that a married woman was acting under her husband’s direction. Ten years later, in 1624, for example, when a hatmaker named Richard Pooke sued Mary Frith, spinster and feme sole, for some expensive beaver hats she had bought eight years before and still not fully paid for, her chief defence was that she could not be sued as a feme sole, because she was Mary Markham, a married woman, who was not legally liable for her own misconduct and therefore could not be sued. Pooke had been warned that Mary had used this trick before to overturn several previous lawsuits, but he fell into the trap anyway and, sure enough, Mary triumphed. It came out in this same trial that she and Markham had not lived together for years, and possibly never had, supporting the theory that, far from being a great romance, this was a marriage of convenience – and clever opportunism – on Mary’s part.[58]