Читать книгу Roaring Girls - Holly Kyte - Страница 9

A WOMAN’S LOT

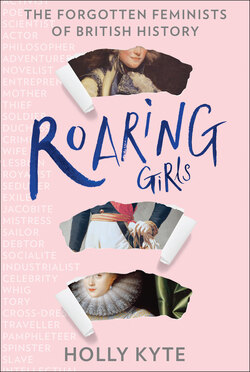

ОглавлениеThe eight Roaring Girls who feature in this book lived in Britain in the 300 years before the first wave of feminists fought tooth and nail for women’s suffrage in the late 1800s, and during those centuries, the political and cultural landscape of the country changed almost beyond recognition. Collectively, these women witnessed the final wave of the English Renaissance and the last days of the Tudors. They saw their country rent by Civil War, their monarch murdered and his son restored. They found Enlightenment with the Georgian kings and experienced Empire and industrialisation in the long reign of Victoria. Britain was transforming at an astonishing rate, yet throughout this period – though it was bookended by female rule – a woman’s legal and cultural status remained virtually stagnant. She began and ended it almost as helpless as a child.

The sweeping systemic changes needed to revolutionise a woman’s rights and opportunities may have failed to materialise by the late nineteenth century, but the first rumblings of discontent had long been audible in the background. By the dawn of the seventeenth century, a radical social shift had begun to creak into action that would falteringly gather pace over the next 300 years. For although Mary Frith was the original Roaring Girl, she wasn’t the only woman of the era to find herself living in a world that didn’t suit her, and who couldn’t resist the urge to stick two fingers up at society in response; the seeds of female insurrection were beginning to germinate across Britain, and the women in this book all played their part in the rebellion.

From the privileged vantage point of the twenty-first century, it’s easy to forget just how heavily the odds were stacked against women in Britain in the centuries before the women’s rights movement, and how necessary their rebellion was. From the day she was born, a girl was automatically considered of less value than her male peers, and throughout her life she would be infantilised and objectified accordingly. Her function in the world would forever be determined by her relationship to men – first her father, then her husband, or, in their absence, her nearest male relation. On them she was legally and financially dependent, and should she end up with no male protector at all, she would find it a desperate struggle to survive.

By the age of seven a girl could be betrothed; at 12 she could be legally married. Her only presumed trajectory was to pass from maid to wife to mother and, if she was lucky, grandmother and widow. Any woman who tried to deviate from this path would quickly find her progress blocked by the towering patriarchal infrastructures in her way. Denied a formal education and barred from the universities, she would find that almost every respectable career was closed to her. She couldn’t vote, hold public office or join the armed forces. The common consensus was that her opinions were of no value and her understanding poor, and consequently she was excluded from all forms of public and intellectual life – from scholarship to Parliament to the press. While the men around her were free (if they could afford it) to stride out into the world and participate in all it had to offer, she was expected to know her place and to stay in it – suffocating in the home if she was genteel; toiling in fields, factories, homes and shops if she wasn’t. Genius was a male quality, and leadership a male occupation. Even queens would have their qualifications questioned by men who assumed they knew better.

The only ‘careers’ open to a woman during this period were those of wife and mother, but even if her homelife turned out, by chance, to be happy, these roles still came with considerable downsides. Legal impotence was perhaps the most obvious. In the eyes of the law, the day they married, a husband and wife became one person – and that person was the husband. From that moment on, the wife’s legal identity was subsumed by his.[2] Her spouse became her keeper, her lord and her master, while she, as an individual, ceased to exist. Any money she might earn, any object she might own – from her house right down to her handkerchiefs – instantly became his, while all his worldly goods he kept for himself.[3] A wife could no longer possess or bequeath property, sign a contract, sue or be sued in her own right. In principle, she was now her husband’s goods and chattels, and he could treat his new possession however he liked. If she were still in any doubt about what to expect from married life before she entered it, the Book of Common Prayer made it alarmingly clear: ‘Wives, submit yourselves unto your own husbands, as unto the Lord.’[4]

If the marriage proved miserable, even unbearable, the wife was expected to endure it. Her husband could beat her, rape her, drag her back to his home if she fled – the law would look the other way. And if he strayed from the path of righteousness into another woman’s bed, well, that was her fault, too; it could only be because she had failed to please him.

With no effective method of controlling her own fertility, successive pregnancies were often an inevitable feature of a married woman’s life, and this brought with it not only the terrors of giving birth, which, quite aside from the pain, could so easily result in her death,[5] but also the horrifying prospect that most of her children would likely not long survive. A couple during the early modern period might expect to have six or seven children born alive, but to see only two of them reach adulthood.[6]

If the marriage should break down altogether, a wife might find herself excommunicated – not just from society, but from those children, too. Like everything else, they belonged to her husband, and he could strip her of all custody and access rights with only a word. If desperate, she might try for a divorce, though if she did, she’d soon learn that she had little or no chance of ever obtaining one. Unless she was rich enough to afford a private Act of Parliament, and could prove her husband guilty of adultery and numerous other misdemeanours, including bigamy, incest and cruelty, the likelihood was all but non-existent. A husband looking to dispose of an unwanted wife, however, might have more luck – he had only to prove adultery in the lady. If all else failed, he could have her committed to the nearest lunatic asylum easily enough,[7] or perhaps drag her to the local cattle market with a rope around her neck and sell her to the highest bidder.[8]

For all these dire pitfalls, the onus weighed heavily on women to marry and have children, yet at any one time during this period an average of two-thirds of women were not married,[9] and their prospects were often even worse. The single, widowed, abandoned and separated made up this soup of undesirables, and with the notable exception of widows who had been left well provided for (they could enjoy an unusual degree of financial independence and respect), they were particularly vulnerable to hardship, poverty and ostracisation. The stigma of having failed in some way marked most of these women. And then, as now, women were not allowed to fail.

Forever held to a higher ideal, women have always had to be better. They alone were the standard bearers of sexual morality; they alone were responsible for keeping themselves and their family spotless. And since society saw no way of reconciling the fantasy of female purity with the reality of sex, it simply divided women into virgins and whores – idolised and vilified, worshipped and feared, loved and loathed. There could be no middle ground; even in marriage a woman’s sexuality had to be strictly controlled, because left unchecked it had the dizzying power to demolish social order. All it took was one indiscretion and man’s greatest fears – cuckoldry, doubtful paternity and the corruption of dynastic lineage – could come true. To avoid this chaos, women were subject to a different set of rules that were deemed as sacred as scripture: a man could philander like a priapic satyr and receive nothing worse than a knowing wink; if a woman did the same, she was ruined. Her reputation was as brittle as a dried leaf, and a careless flirtation or a helpless passion could crush it to dust. So rabid was this mania for sexual purity that it could even apply in cases of rape – so rarely brought to court and even more rarely prosecuted, though women undoubtedly endured it, and the shame, blame and suspicion that went with it.

These pernicious double standards permeated every form of social interaction between the sexes – even the very language they spoke. The nation’s vocabulary had developed in tandem with its misogyny, resulting in a litany of colourful pejorative terms designed to degrade and humiliate any woman who proved indocile. Too chatty, too complaining, too opinionated and she was a nag, a scold, a shrew, a fishwife, a harridan or a harpy. An unseemly interest in sex saw her branded a whore, wench, slut and harlot. And if she ever dared succumb to singledom or old age, she deserved the fearful monikers of old maid, crone and hag. Terms such as these were part of people’s everyday lexicon, and they have no equivalents for men.

Such thorough disenfranchisement – intellectual, economic, political, social and sexual – was the surest way to keep women contained, but despite these desperate measures, it remained a common gripe that women didn’t stick to their predetermined codes of conduct anywhere near enough. They were sexually incontinent, fickle, stupid and useless. They gossiped, carped, prattled, tattled, wittered and accused. They had even started to write books. If they would not shut up and play the game, they would have to be forced, and in these tricky cases, ostentatious methods were called for.

A nagging, henpecking or adulterous wife who had overleaped her place in the hierarchy, for example, might be ritualistically shamed in a village skimmington or charivari – in which her neighbours would parade her through the streets on horseback, serenading her with a cacophonous symphony beaten out on pots and pans, and perhaps burning her in effigy, too. Alternatively, she might be subjected to the cucking stool – an early incarnation of the more notorious ducking stool – which essentially served as a public toilet that the offending woman was forced to sit on. And there could hardly be a more sinister or more blatant symbol of the systemic gagging of women than the draconian scold’s bridle – an iron mask fitted with a bit that pinned down her tongue, sometimes with a metal spike, to quite literally stop her mouth.[10] This unofficial punishment, which was particularly prevalent during the seventeenth century, was mostly reserved for garrulous, gobby women who had spoken out of turn (or just spoken out) and challenged the authority of men, but it might also be meted out to a woman suspected of witchcraft – if she wasn’t one of the thousands who were ducked, hanged or burned for it, that is.[11]

These elaborate tortures pointed to one simple fact: that the potential power women had – be it sexual, intellectual, even supernatural – scared the living daylights out of the patriarchy. In response, it did everything it could to suppress that power and preserve its own supremacy: it kept them ignorant, incapacitated, voiceless and dependent.

By the dawn of the seventeenth century, this sorry template for gender relations had prevailed largely unchallenged for millennia. It’s a model so deeply entrenched in Western culture that it can be traced right back to the Ancients, who set the gold standard for excluding and silencing women, not only in their social and political structures but in their art and culture, too.[12] Its justification was based on one disastrously wrong-headed assumption: that women were fundamentally inferior to men. And for that we can blame both bad science and perverse theological doctrine.

Even today, we cling to the myth that men and women’s brains are somehow wired differently – an idea that modern science is rapidly disproving.[13] But in 1600, the belief that gender differences were every bit as biological as sex differences was absolute. Ever since the Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle hypothesised that women were a reproductive mistake – physically defective versions of men – it had been persistently argued in Western debate that they were mentally, morally and emotionally defective, too. It didn’t help that seventeenth-century medicine had also inherited from the Ancient Greeks the nonsense theory that the body was governed by the ‘four humours’ – blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile – which in turn were thought to be linked to the four elements: earth, fire, water and air. The belief was that a woman was comprised of cold, wet elements, while a man was hot and dry – a crucial difference that supposedly rendered her brain softer than his and her body more unstable. The catastrophic conclusion was that women had only a limited capacity for rational thought. It was no use educating them; their feeble brains couldn’t bear the strain of rigorous intellectual study. They could not be trusted to think and act for themselves, which was why they required domination. And their bodies and behaviour had to be constantly policed, because women were famously susceptible to both sexual voracity and madness – which frequently went hand in hand and were often indistinguishable.

These pernicious, ancient ideas were only reinforced by Christian doctrine. The creation myth made it abundantly clear that Eve, the first woman and mother, who had been fashioned from Adam’s rib for his comfort and pleasure, was the cause of original sin and the source of man’s woe, while early Christian writers spelled it out to the masses that it was a wife’s religious duty to bow to her husband’s authority, because ‘the head of the woman is man’[14] and to submit to him was to submit to God. By the seventeenth century, the damage had set in like rot. The message had been parroted and propagated by nearly every father, husband, preacher, politician, philosopher and pamphleteer across the land for thousands of years, until almost everyone – even women – believed it.