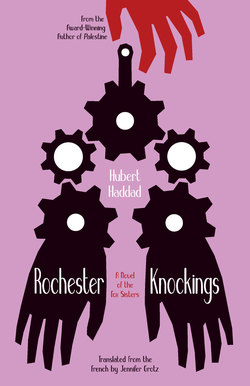

Читать книгу Rochester Knockings - Hubert Haddad - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеVIII.

Polk’s War Was not a Polka

After the arid mountains of the west and the rocky deserts of Arizona, after the perilous canyons all along the Colorado River where he had escaped from the Mescaleros’ arrows without much trouble, after the ambush with rifles of a band of Catholic deserters returning to their fold, the plain stretched out, infinitely calm. He was leaving behind him Denver and the memory of a night drenched with whiskey in a smooth featherbed. In the saddle on one of his two horses, for three solid weeks now, William Pill had been making his way on the paths leading north, fixed trails grooved by herds of cattle and settlers’ carts in a simmering sea of wild grasses. When the Appaloosa grew tired, he climbed onto the Spanish Barb relieved of his baggage, and so on, from one point of water to the next. The Great Plains were for him the image of a rough paradise without demarcations that left one with complete freedom of movement: all this blondness moving under a sky vaster than the memory of humankind! Step by step or at a gallop, in no hurry, he was returning from the war with a Certificate of Merit in his pocket for having followed General Zachary Taylor on the Santa Fe trail and later distinguishing himself alongside Old Rough and Ready on the heights of Buena Vista. But his greatest achievement as a free man would have to be enduring life in the barracks for months on end in occupied territories, waiting for the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the masterpiece of Manifest Destiny and flying artillery, to be signed: several million dollars of compensation to the vanquished, in return for the reattachment of half of Mexico to the Union, not to mention Texas!

Thanks to the amnesty decree granted to the heroes, William Pill could openly go home. It was just a matter of deciding what home to go back to. All his life he had burned bridges, starting with those rickety ones, his ancestors’, leaving Dublin at the age of fifteen on one of those coffin ships that unloaded the white pines from the Ottawa Valley and then left again with a load of immigrants driven from their land by famine, epidemics, and landowners. Five weeks of crossing on the Brotherhood—a four-hundred-ton former slave ship bought and renovated by a Quebecois ship owner—a sailing ship with three masts, its holds and decks filled with hostages of misery, this time all white and red, had cured him once and for all of belief in divine mercy, after the dreadful overcrowding, the surliness of the crew, a cyclone that carried away the rowboats from under tarpaulins along with a number of reckless passengers clinging inside, the typhus striking the children first and finally one girl in quarantine at Grosse Île in the company of the dying. Many, well before reaching that hellish haven, had been cast in a bag into the sea with the benediction of a priest there for the occasion. One woman thought to be dead had started screaming as she slid down the tipping plank without the sailors even attempting to catch her. Pill had not forgotten the little girls thrown to the sharks under their mothers’ blanched stares. During the crossing, on a mission to Manitoba, an evangelist of the Plymouth Brethren named Edward Blair had by chance befriended him, sharing his victuals and incessantly reading aloud from an oft-consulted Bible even though he already seemed to know each verse by heart. He was the disciple of a German immigrant, the famous George Müller, a former thief and lecher who carried heavy remorse for being drunk during his mother’s dying days. Once converted, he devoted himself to orphans, creating schools everywhere, saving them from destitution by the tens of thousands. On the baleful three-masted ship, Edward Blair had all the time in the world to recount his meeting with the German. The reread Bible he ceaselessly consulted was a goodbye gift from the missionary. Having himself in turn become one of the brethren, he had read and reread it every hour of the day without damaging it, then with his hand on the black binding, nourished his own preaching with it. Aboard the Brotherhood, in the turbulent sea, the only one who listened to him was an illiterate son of famine. The brethren who left to evangelize America hadn’t even succeeded in converting that Irish boy who nonetheless inherited the Bible upon his friend’s death. When they threw the cloth-wrapped cadaver overboard, the young immigrant couldn’t stop himself from opening the book randomly with the certainty of hearing there the friendly voice of Edward Blair.

And the channels of the sea appeared,

The foundations of the world were discovered,

At the rebuking of the Lord,

At the blast of the breath of his nostrils.

After the required stay on Grosse Île where many other passengers of the three-masted ship perished and where an old prostitute taught him how to dance the polka, William Pill finally disembarked in Quebec, where he promised himself to always keep his head above waves, men, and steeples.

At this hour, with no memory of the Old World, the high plains unfurled before him a finally unpopulated sight, immensely empty, with only the wind, the light, scattered birdcalls, the vacant call of the coyote, and, under the sun’s vibrant haze, from a distance, the final foothills of the Rainbow Mountain Range. His Spanish Barb escorting, he was riding the Appaloosa with a shoulder still hurting from the musket shot he suffered during the Battle of Huamantla. After so many days and nights of the sleepy rhythms of horses, Pill had the curious impression of the deterioration of his bearings, of an irreparable loss, as if he were leaving bits of himself on the road, a trail of images flowing down the back of his neck pierced by oblivion. Of his childhood, what still remained today? Not even a face. Sometimes when dusk was holding back its golden wine of shadows, he ruminated over the vague memory of hyacinths in his mother’s garden. But he was alone with the sky. His Springfield rifle ready for use—an 1840 flintlock musket converted to percussion lock—he wondered for the moment if he would find enough among the tall grasses to make a fire to cook the coveted rabbit or quail.

The sun was still full above the hills, but the azure was already darkening on the curved horizon. A couple of buzzards circling in flight drew his attention to the carrion of a mustang being swept by the wings of other raptors. The rider was found close to his mount. Burned in areas and across vast distances, probably by bison hunters, the grassland had dried up little by little to the advantage of bare fallow lands where loose gravel rose to the surface. He continued his voyage at a small trot, satisfied despite the hunger that gnawed at him to see the appearance of the evening star that the Mexican Indians at the officers’ service identified with Quetzalcoatl, their feathered serpent god. Soon some construction stood out at the bend of the trail leading away from the lands unfarmable at this height. A painted wooden sign indicated Osage City. He rode past a tank perched on a scrap iron frame, past gaping barns, some of them in ruin, their metal roofs collapsed over a heap of wooden planks and old fodder. The agglomeration seemed perfectly deserted, abandoned to the winds. Dust from the road blinded windows and the storefronts of pharmacies. Piles of blackened boards alternated here and there with still inhabitable structures. By the looks of the signs on flaking façades, the enclosed spaces to tie up horses and the numerous saloons, there had once been a life here of hustle and bustle. Pill told himself it would offer him and his horses the best place to stay. Lacking a woodcock, a crust of bread and a can of corned beef would garnish his table instead. At that moment, some sort of wild pig crossed the road. But the gun was in his holster on the other horse, and by the time he could seize it, the creature had turned the corner at a watering trough. In pursuit, this time with his pistol in hand, Pill came across a black albino in a top hat and suit, sitting on a box under the drugstore’s awning. The peccary, behaving just like a dog, was lying quietly at his feet.

“Might you be thirsty?” said the stranger, holding up a flask of rum as the rider came to a stop twenty yards away.

Pill jumped off his saddle and holstered his gun. Once his horses were tied to a fence, it didn’t take long to share the bottle’s contents. The man took off his hat, revealing a bald lily-colored head.

“So you’re heading home with a wounded shoulder and a soldier’s certificate of merit to New York State? As a former slave can well tell you, that’s a free land under Heaven’s protection.” The starry night stretched out quickly over the ghost town’s clandestine day. At the side of the road, under the drugstore awning, the two men shared a dish of lentils.

“I don’t miss anything,” said the albino, “not even the masters of my youth, papists who taught me how to read with blows of the whip. Look, this whole town is mine. After they saw all the wagons coming from the east and the north going by, the folks of Osage City ended up following them. Horse breeders and farmers who were killing each other here like Cain and Abel over the slightest dispute, left arm in arm as soon as they got wind of the news: tons of gold in the west, on the other side of the Sierra Nevada. All you had to do was stoop down to pick it up. There they went, all of them, leaving anything that didn’t move behind. Without any customers, the shops closed, the pastor put away his sermons, the sheriff turned in his badge . . . Now there’s nothing left here but me and this pig. Freedom, that’s my gold. Nobody picks a fight with me, the Kansas Indians went back to being peaceful once they were allowed to hunt bison again. Once the whites had left, they burned all their empty ranches and farms, wheat fields, to give the grasslands back to the wind, as the Kaws say. They’re not called the People of the Wind for nothing. The day the Indians started throwing torches into this village, I jumped out of my hideout and yelled: “Osage City is my house, don’t burn it!” I think they took fright of me. A pale Negro materializing out of a ghost town wearing a top hat must surely be a demon. They got back on their horses and, howling like coyotes, off they went!”

William Pill, who had listened to his host for much of the night, thought for no reason of the words to a Mexican song that used to come to him in snatches while in the enemy camp, shortly before dawn, when he was preparing to defend by cylinder cannon a hacienda on a steep pass.

Who will rip out my heart’s flower

What jaguar of chalk, what eagle of blood