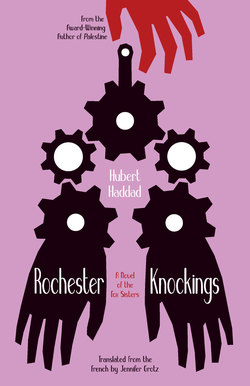

Читать книгу Rochester Knockings - Hubert Haddad - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIX.

The Night of Sleepwalkers Recounted by Maggie

There’s too much craziness right now. My sister Katie must be the devil, or maybe just his wicked little daughter. I’ve written it out just as I understood it, in this notebook Miss Pearl gave me. It started with knocks on the floor, or rather beneath it, seven and eight times, in clusters, in the exact spot of our bed. That March night and the ones that followed it, Father didn’t sleep at home. Squeezed into his venerable black suit, the one for weddings and funerals, he took the stagecoach to Rochester. The poor old man got it in his head that he should open a credit account at the bank, so he gathered his savings in the bottom of his gusseted bag, not a large amount, I imagine. He announced that he would use the opportunity to visit Leah. Our older sister, by coincidence, needed his signature for a right to lease. She gives piano lessons to the daughters of rich flour mill owners in Rochester. Leah despised our way of life. She only loved pretty manners, fancy dresses, and handsome men. The eldest of the Fox sisters dreams of marrying one of the town bourgeois. And at the age of thirty-five, with a few gray hairs, it would be time!

We were alone with Mother last night when the knocks started up again. Katie, who was pretending to sleep, sat straight up as if spring-loaded. I am always just as terrified when she gets up and walks toward the window or staircase with her arms outstretched, eyes rolled upward. But this time it wasn’t a case of sleepwalking. In the darkness of the bedroom, I could easily see her crafty look, almost cruel when she smiled. Katie is adorable, all slim, with the pretty figure of a theater actress, but there is a bit of a demonic look to her. It could be said that anywhere she finds herself—in the forest, in the village, in the house—she is looking for the secret behind things.

One autumn day (we had spoken the night before at the dinner table of Joe Charlie-Joe, the former slave of the Mansfield ranch hanged from a big oak in Grand Meadow), I noticed Katie preoccupied with blowing on spider webs in the basement while murmuring a stupid nursery rhyme:

Catch me if you can

I’m the spirit of a fly

Devour me if you want

I’m the soul of a hanged man

Sitting in bed, a little later, she all of sudden started to snap her fingers, thumb against middle finger, like the black day laborers who sing prayers after pulling up the corn. I couldn’t stop myself from copying her. We were snapping our fingers in rhythm and then suddenly, Kate called out: “Whoever you are, now do as we do!”

It must be said that the silence of the night overtook us after that command. There is nothing more painful than the silence that follows an incomprehensible phenomenon. Everything was quiet outside, one could distinctly hear the barn owls and the coyotes. Having been spared one night of her husband’s snoring, Mother was sleeping, hands curled into fists. There were soft crashes against the windowpane that could only be a moth in the cool air of this end of March. Without Father’s help, Mother had been too busy with a thousand other tasks to make our bed and bother with the windows.

“Do as I do!” Kate repeated with authority and loudly cracked the knuckles of her fingers. Suddenly, I write this under oath, we heard the exact same sound echo back. But it was an echo that was so close by! Kate exulted. She was terribly excited. At that moment, I believe she hadn’t really imagined the significance of such a phenomenon. Aside from fairies or conjurers, nobody in the world had ever experienced this: we were ordering the invisible to manifest itself and, for the first time since our Lord Jesus Christ, the invisible was answering back! There was my sister who had leapt out of bed and planted herself in the middle of the room, her arms on her hips: a real leprechaun in the dark with her nightgown all tangled mid-thigh.

“Are you a man?” she dared to ask with that hoarseness the voices of girls sometimes have. When there was no response, she continued her line of questions. “Are you a woman? A child? An animal?”

Katie scratched her head and turned toward me. “Help me—do you have any ideas?”

“Maybe we could ask its name and age?”

“That’s not easy, if it’s nobody! And then how would it tell us? The thing only communicates by noise, or at least little knocks, little purrs of a tiger in hiding . . .”

Kate started to turn slowly in place. She fixed herself, arms spread, like a statue. “Are you a spirit?” she then exclaimed, intimidated by her own question.

We heard two knocks of acquiescence, very clean, same as the blow of a hammer or sweep of a broom. Frightened but radiant, Katie came with a leap to join me in the bed.

“We did it!” she whispered in my ear. “It’s a ghost . . .”

With these words, not yet having understood the power such a word could apply, in terms of the invisible, I felt the ice water of terror rise up my throat. Kate firmly clamped both hands over my mouth to stifle the scream swelling up in me.

“Hush!” she said. “Ghosts are shyer than a moon rabbit . . .”

Regaining my breath, I hissed back in panic. “And what if he wants to drink our blood or make us pregnant?” The whites of Katie’s eyes and her sharp little teeth sparkled in the dark.

“Shh!” she said without reassuring me in the least. If it was a ghoul or a vampire, we were soon to be dead for good.

It might have been one in the morning. The house became unusually quiet again but I could tell that all sorts of insanity was brewing inside Katie’s skull. “One thing is sure,” she said finally, “the spirit understands our English, but he seems to have swallowed his tongue, or else Mister Splitfoot has the voice of a mouse, too soft to cross the wall between his world and ours . . .”

Mister Splitfoot! Where did she come up with such a name? Her penchant for mischief is apparently endless.

The exceptional silence of the walls and furniture made her loquacious:

“Imagine a deaf person and a blind person each lost in a thunderstorm. One isn’t able to hear the thunder and the other one

is unable to see the flash. Neither would be able to escape the lightning . . .”

“What are you trying to say, Katie, putting on those marmoset airs of yours?”

“That the two of us are not in danger of being surprised by the storm . . .”

My little sister likes enigmas. And she likes songs even more. When she began to hum one of her favorite nursery rhymes, I must have fallen asleep, lulled by her voice . . .

What’s your name, Mary Jane

What’s your number, Cucumber

My dream continued the adventure from earlier in the night. Except that Katie was in my place and I was in hers. In my case I had kept my reserve as opposed to her playful pixie behavior and I was quite surprised to see myself suddenly intrepid, there, across from the body I was occupying, that big carcass of an adolescent who no longer belonged to me. Anyhow, we descended the staircase, one of us bizarrely in the other, me in her and her in me, and I couldn’t tell anymore which of us was trembling so much that the entire house felt the tremors. “Let’s not be afraid,” I said to Katie in my body, “there is always a step after the last step.” Through the open door of the woodstove, tongues of fire shot up while it roared all the way up its thick iron stovepipe. Leaning over to shut it, despite the intense heat, I saw in this aquarium of embers the skeletons of children the color of molten iron. They were moving slowly like long delicate fish, sea needles, or seahorses. My mirror-faced sister tugged at my sleeve.

“Come on, come,” she said in unknown words, “the fire will go out all by itself.” We let ourselves flow immediately into the swirl of a staircase of whitewater that seemed familiar to me, even if I had not forgotten that a sort of riveted wooden ladder was what led down to the basement. We slipped at full speed down those step-shaped wavelets until soon underground, in the middle of the roots of cedars and tall pines. Green glowworms were performing the service of streetlamps in these depths.

At another moment, I had the sensation of myself being buried in an old rock salt mine or in one of those caves all vaulted with the ribs of branches in full sun. Katie, my little Katie transformed into Maggie (what an unpleasant impression of stiffening!), already below me exclaimed, “It’s Mister Splitfoot! Here he is in his manor house! Mister Splitfoot in person . . .” And singing out loud at the top of her voice without my being able to see who it was, aside from a wicked will-o’-the-wisp climbing up from the entrails of the earth:

Where do you live?

In the grave!

What is your favorite song?

Hello maggot!

Waking with a start, I realized that my bedfellow had hardly finished her nursery rhyme, also perceived with strange deformities, and that my dream had lasted the length of a yawn. But either from precaution or superstition, I felt first for my breasts, rather developed for my age, then for my sister’s almost nonexistent ones.

“What’s gotten into you?” Katie was irritated.

“Oh nothing, really!” I said without laughing. “I just wanted to assure myself that you weren’t me . . .”

Timidly, with one arm numb, I asked if she would repeat the end of her little song.

“What song?” she asked with surprise.

“You know, ‘Where do you live . . .?’”

“Oh, Mister Splitfoot’s nursery rhyme! I don’t remember it very well anymore. Wait, it’s coming back to me:

What is your name? Horn of the chin

What is your number? Zero plus zero

What is your country? Far from paradise

What is your address? Street of Two She-devils

Where do you live? In the black house that kills