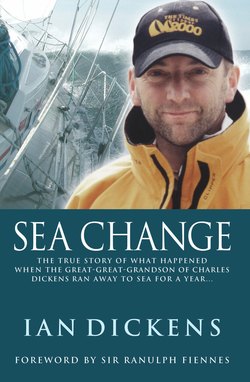

Читать книгу Sea Change - Ian Dickens - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

ADVERTISING WORKS

As a marketing man I’d spent much of my time proving to companies that investing money in a fine advertising agency generated an excellent return for them in terms of additional sales.

At the end of the following week, the marketing people at a company called Clipper Ventures could make the same claim to their superiors. They had created a single-page, colour, right-facing ad and booked space in the Sunday Times supplement. All they had to do was sit back to wait for a reaction and they didn’t have to wait long to get one from me.

A picture of an ocean-going racing yacht storming along under reefed sails on a wave-flecked ocean. A headline beckoning the adventurer. A number to call. The seductive line that offered the bored breakfast-table reader the chance to break away and achieve something truly exceptional. Anyone, the ad said, could earn themselves a place on board and compete in a yacht race that circumnavigated the planet.

It was a potential answer to all my problems – except for one or two minor details. I needed to find £23,000. I would have to take a year off. I needed to persuade my wife that it was a brilliant idea. I would have to tell my children that I would be away in a risky environment for longer than they had ever experienced. My proud parents would have to be told that I would probably have to give up my hard-fought career. The bank would need to know that the mortgage and bills would still be met despite my being (a) out of the country and (b) having no income. I would need to tell work that I wanted out.

Minor problems that were exacerbated by a rather too large overdraft and a less than friendly work environment that would probably not take too warmly to the request of a sabbatical.

But for now all that could wait. All I needed at this stage was a brochure that would tell me more. Once I got that I could start to consider a plan of action that would begin with suggesting to my wife, as subtly as possible, that this was one of my better ideas.

A difficult task to find the right opener and I started to rack my brain for the best way of breaking the news. In Sainsbury’s perhaps, as we walked through the produce of the world. ‘Look, darling, bananas from the Dominican Republic. Wouldn’t it be fascinating to sail there? Oh look, pineapples from Hawaii – did you know that an English-run yacht race calls in at Waikiki? Dolphin-free tuna – so important to protect the ocean, don’t you think?’

Maybe not.

Perhaps a wistful look through my father’s photo albums, where images of his father and brothers joined Dad on the bridges of a host of great warships. As I looked at their gold-braided sleeves, I could perhaps summon up a misty-eyed detachment that might be translated as a desperate yearning for the sea. A tad too melodramatic perhaps.

Maybe it should be a mid-life crisis style breakdown. Allow it to seep out late one night after several Scotches, with a head-clutching moan of despair and an Oscar-winning delivery: ‘I can’t go on like this.’

Not unless I wanted to get a firm slap followed by an abrupt demand to pull myself together.

The problem was solved by Holly.

Holly is my daughter – fourteen at the time of this attempted subterfuge and, as is true for any father anywhere in the world, the most beautiful and perfect daughter a father could wish for.

Sparky, fun, honest, stunning, coy and the owner of a long and languid pair of legs that were the first thing I spotted coming down the stairs as I hastily finished dictating my address into the Clipper Ventures mailbox.

‘What are you doing?’ she asked, wrapping her equally long arms around my waist in a loving hug. Over my shoulder, she studied the hard-working ad, taking in the content with a sweep of the eye.

‘Are you thinking of sailing around the world? Cool.’

I had not intended to talk to anyone – even to consider planning anything – until I had seen more details. The race demanded volunteers and there was a selection process to get through. There was no point getting my hopes up, or winding up other people, until I knew exactly what my chances were.

Before I could explain to Holly that she had got the wrong end of the stick, Anne appeared at the front door with a huge clutch of Sainsbury’s carrier bags hanging from each arm. One of the bags was ripped badly at the handle and my wife was involved in a frantic battle to deliver it to the floor before gravity took over. It looked like the shopping trip had not been the highlight of her weekend and the tearing plastic was the conclusion of a less than satisfactory hour away from the house. I took in the heavyweight contents of the bag, which appeared to be made up of several large and ripe pieces of fruit from far-flung corners of the world, and wondered if there was a chink of an opening for my carefully rehearsed argument.

The bag finally crashed downwards, spilling melons and mangoes on the floor, and as they rolled away a steady stream of fine Anglo-Saxon, broadcast in a broad Irish accent reserved for such occasions, issued forth amid the exotic trifle that surrounded our feet.

I chickened out, mainly through a sense of self-preservation, but also because my daughter had got there before me.

‘Dad’s thinking of sailing round the world,’ she airily announced to the harassed figure still standing in the door. Holly now also took in that her mum had clearly not entirely enjoyed the aisle tour of the world’s food markets and the remark was not timed to be the most helpful. The sound of all the other bags hitting the stone floor in an orchestrated crash made my daughter jump, me tremble and scared the dog, who headed through the polythene jungle out into the sanctuary of the garden.

I had a sudden desire to follow.

There was shock, of course, at the intention of electing to spend a year apart. There was an instant demand to know much more about the year away. What was this event? When did it start? How much did it cost? Did I intend to apply for the whole race or do just one of the legs? How would I raise the money? How did I feel about being apart for the best part of twelve months? What about the job? What about the mortgage? What about the children? What about us?

A whole series of immediately practical questions rather than the much more obvious, ‘No bloody way, sunshine.’ It was typical of the woman I had been married to for eighteen years, and a complete contrast to the reaction of some of her friends, who over the following months would exclaim, ‘But how could you let him?’

Anne viewed their behaviour as downright selfish. ‘No, you can’t be allowed to experience the thrill of travelling around the planet, because we want you here at home. Get back to work, pay the mortgage, mow the lawn and put up the shelves.’ She viewed me as far more than a cash-supplying handyman commodity and was cautiously excited about the magnitude of the trip. And if she was hurt by my decision, then she hid it brilliantly well. Perhaps because she had an ulterior motive.

For the past couple of years, family holidays – paid for by my generous director’s bonus – had seen us hoisting sails on board a variety of yachts in the heat of the Mediterranean summer.

Just three weeks before this awkward confrontation, we had nudged gently up to a rough wooden jetty beside a sandy beach in the backwaters of Turkey. Our yacht-handling skills had been viewed with scarcely concealed nervous relief by the owner of a well-used sailing boat with a tatty red ensign flying from the stern. He and his wife, dressed in battered T-shirts and worn shorts, had been busy hanging out a curious assortment of washing as we hove into view.

With a nautical version of ‘Janet, donkeys!’, they were off the boat and ready to repel anything that looked like it might damage their precious home. The safe arrival of our mooring ropes on the quay had calmed their fears and we had an amiable chat in the warm sunlight.

The couple were two professionals from the UK who had done their fair share in the boardroom and decided to opt out and gently cruise from one hot spot to the next on a boat that contained all they really needed in life. Anne, in particular, had envied that freedom and, long after we had waved goodbye the following morning, we fantasised about one day adopting an equally simple lifestyle.

The days where even a swimsuit would be overdressed. Days free of TV and newspapers, commuting, lawnmowing, council tax, parking fines, speed cameras and party political conferences. Days free of meetings, voicemail, impossible deadlines, the M25, traffic reports, litter-strewn streets, floods, shops that stock Christmas crackers in September, Easter eggs in January and Halloween masks in August. Days free from privatisation, ensuing train crashes, sabre-rattling warmongering and ‘Two Jags’ Prescott. Days free from an environment where loyalty was no longer valued and blinkered self-interest was deemed so normal that complaining about it was considered to be the start of a nervous breakdown.

The opportunity to do the ultimate journey around the world under the guidance of a professional would be a fantastic learning opportunity and Anne saw the Clipper Ventures idea as a sound investment in her own dream. It was a brilliant argument and one that I wish I’d thought of when faced with that awkward carrier-bag moment of explanation.

There were still inevitable concerns, and over Sunday lunch we began to touch on the issues. How would we pay for the trip? How would the mortgage be met while I was away? What would the separation do to our relationship? How would the children react? What if I fell overboard and didn’t come back?

While I had already been rumbled by Holly, twelve-year-old Michael was out doing what twelve-year-olds do. Riding bikes, kicking balls, swinging from trees and dreaming up far-fetched games that were acted out on the village green in front of our home.

He arrived back for lunch, breathless, wreathed in sweat, and headed straight for the sink and a glass of frantically gulped water. Like Holly, he took in the concept with an easy acceptance and, as the debate continued, the materialistic thrills came into view.

As I shared the route, savouring for the first of many times ‘Portugal, Cuba, the Galápagos, Hawaii’, Holly interrupted me.

‘Does this mean we can go to Hawaii?’

‘Quite probably, yes,’ I guessed, and that was it. As far as my children were concerned, the trip was a definite, and she drifted off into planning bikinis and the bags required to carry them.

Michael held out a little longer and my travel itinerary continued through Japan, China, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Singapore, Mauritius, Cape Town, Salvador, in Brazil, and New York.

One leg away from returning home, he too had found his own Eden, becoming instantly smitten with the idea and wondering whether Nike Town should be the first port of call or perhaps it should be the Empire State. Whatever, it would be vital news to airily lob into the classroom on Monday morning, despite my dire warnings to say nothing at this stage.

I noticed that Anne, trying her best to be hard-nosed about the travel prospects, had visibly wilted when I had mentioned the Galápagos Islands.

But until I had a place on board there was little point in going any further. I had no idea of the criteria the organisers were looking for, and might well find myself on the receiving end of a reject letter saying, ‘No mid-life-crisis candidates required. Good luck with the rest of your life up a dead-end street. Kind regards, Sir Robin Knox Johnston.’

Stopping the conversation now would also allow me to open another bottle of red, put the globe on the table for an in-depth study, find where the dog was hiding and tell her it was safe to re-enter the house.

I decided on one thing, though. Should I get a place, I wanted to start and finish the entire race on board the yacht. I had to complete the journey and deal with all the challenges it had to offer. The sensible option (which I had hardly taken in from the ad) of doing a six-week leg, taking the time off as holiday and funding it by cashing in an insurance policy, was far too practical. If you mean to do it, then it should be all or nothing and the difficulties placed in the way would all be part of the challenge.

If we were going to worry the bank and the mortgage company, then let’s really give them something to fret about.

I filled up Anne’s glass, the children went in search of the atlas and Raggles settled back down in her basket and nodded off to sleep.