Читать книгу Sea Change - Ian Dickens - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

EASY GOODBYES

ОглавлениеClipper Ventures, true to their promise, sent through a pack of information and an application form a couple of days later. Meanwhile I had been to the website and was already hooked by the adventure. I really did hope that Sir Robin, the man at their helm, had a soft spot for middle-aged businessmen trying to find more from life, because I now wanted this very much indeed.

Anne and I filled out the forms, thinking long and hard about the testing questions that asked for a very honest, warts ’n’ all opinion about myself. These were clearly the ones that would give an insight into my personality and provide clues as to whether I was made of the right stuff.

We agreed that a cheeky response was the best approach, and that summed me up anyway. If they were looking for a bunch of military-style squaddies, with fun and banter banned, then perhaps the event was not for me.

I stuck it all in an envelope with a good-luck pat and Michael hurtled across the green on his bike to the postbox, demonstrating a fearful disrespect for the laws of gravity and tyre adhesion.

When the post arrived a couple of days later, among the envelopes was one with a Clipper Ventures postmark. Not an A4 folder full of information this time, just a simple regulation envelope with what felt like a single-page letter inside.

Suddenly I was sixteen again, looking at the faces of my parents, knowing that the O Level results would either thrill or disappoint. The affected lack of interest, the studied indifference from around the breakfast table, belied the nervous anticipation in the room. As in the days of exams, I wanted to run and hide under the bed or lock myself in the loo before reading if Sir Robin had made the grave error of deciding I was not even worthy of an interview.

First I opened the bank statement and the long line of numbers adding up to one big OD suggested that knuckling down to earning more cash was the sensible option for the next few months. Or decades.

Reader’s Digest offered an escape route in the next envelope, advising me that I had been selected to win at least a million. There was some tedious small print regarding the purchase of a book that detailed fascinating facts about ‘healing plants of the world’. So confident were Reader’s Digest that the money was virtually mine, I wondered if Lloyds might take the ‘YES’ sticker as down payment against the overdraft, and was tempted to stick it to the bank statement before posting the whole lot off again.

The third envelope could wait no longer, so I opened the life-changing communiqué and read its content. Never has anyone been happier to receive an invitation to the small market town of Olney and have the potential of adding £23,000 to their bank-account burden. While Anne, Holly and Michael whooped their enthusiasm, I too had to admit to feeling just a trifle happy. After all, with Healing Plants of the World in my bookcase, my financial problems might be well and truly solved for ever.

On the train to King’s Cross I dreamt of what might be. The problems at work that had been getting me down so much were suddenly hugely diminished and I realised how badly I wanted this new chance. The fields of Bedfordshire gave way to the suburbs of north London and, as row after row of terraced houses crept by, I was off in a frenzy of escape, in the midst of a sun-kissed distant ocean with dolphins splashing all around. The whole idea was wonderfully romantic.

The romance continued when I offered to kiss Clipper’s marketing manager.

We met a week later in a small industrial estate on the outskirts of Olney, in an office about as far from the sea as it was possible to get. Sitting nervously in the company’s reception area, eyeing a couple of other candidates suspiciously, I wondered how to approach the impending grilling. Here was yet another new experience for a man who thought, rather too arrogantly, that he had experienced most of what life had to offer. My interview technique had become decidedly rusty and I had no idea of where the probing questioning might go.

In the end it turned into a really good chat, which I enjoyed hugely. After an hour in which my technique had included a mild dose of pleading, the interrogator looked at his watch, snapped his pen shut and uttered the immortal line, ‘Thank you, we’ll let you know.’

I was completely in the hands of someone else and it left me feeling distinctly uncomfortable.

A couple of days later another letter arrived from Clipper. It contained three paragraphs, the most important of which started with the word ‘Congratulations’.

If I was ecstatic, so too was Anne, even though she was entering the foothills of a deep journey of discovery. Ever practical, she was acutely aware of the potential pitfalls that lay on the paths ahead. This was not just an idea any more, a fantasy played out over a bottle of wine. This was real, a black-and-white absolute fact that could be life-changing in ways that might unearth our deepest fears. But she remained totally and utterly positive, despite that troubling prospect.

Touchingly, Michael and Holly were also nothing other than completely thrilled and their excitement matched my own. While Anne, as an adult, could think things through with a practical logic, the children were surely allowed to have selfish moments of feeling sorry for themselves at the year-long loss of Dad. Their reaction was such a spontaneous act of support that tears pricked my eyes as they smiled smiles of real happiness for my adventure. I was going to be away from home for the best part of a year to follow a personal dream, but not an ounce of selfishness entered their thoughts.

When I spoke to my new best friend at Clipper to thank him for his brilliance in character judgement, the offer of the kiss was laughingly dismissed and replaced with a couple of much more practical issues.

Paying the money and booking up for training.

I had yet to resolve how we might pay for it all, but still Anne remained completely positive. She was adamant that, having come this far, I would be mad to turn the opportunity down, no matter what problems work might put in my way to quash the dream.

‘You’ll kick yourself for ever if you don’t do it,’ she admonished, fully aware of the responsibilities I had towards her, the children, our home, Lloyds Bank and, if they were lucky, Reader’s Digest. For several weeks there was a small niggle that refused to go away, especially late at night as I tried to get back to sleep. It whispered words like ‘irresponsible’, ‘fool’ and ‘idiot’ as an incessant nag. But Anne had quietly spotted the signs and was already heading them off at the pass.

I e-mailed Barry in his retirement idyll of Miami and he concurred with Anne’s view. We had kept in regular contact and he knew that work was becoming an increasingly challenging experience for me. He also knew that the longer I stayed a part of it, the unhappier I would become. But he urged me to do the race for far bigger reasons. He and Wendy, his spiritual and visionary wife, knew that the journey would offer a set of experiences of such clarity that my eyes would be opened in a way they had never been opened before. Whatever the future held, no one could take away the experiences that sailing around the world would provide.

My parents were also completely on side. Dad loved the idea of another family member going to sea. He loved the idea of the seamanship involved and the scale of the journey. More importantly, both my mother and father thrilled to the boldness of my decision, recognising that I felt able to turn my back on convention and dare to dream a completely impractical dream.

They had watched with growing dismay, they now confided, the pressures a modern directorship puts one under. They could not understand the amount of travel, the meetings, the punishing schedules that were asked of me and, like any parent, they worried at the toll it might be exacting on their son. There he was, perfect material for being struck down by one of the dangers that come stalking people in their mid-forties. A narrowed artery struggling to deal with high blood pressure, perhaps, or a sudden tumour (as my poor workmate had demonstrated). Or maybe an exhaustion-driven nodding off at the wheel, ending in a somersaulting, horn-blaring wipe-out on the A1 in the middle of the night.

They saw my decision as nothing other than a truly positive step and realised how difficult the debate must have been to arrive at that point. Any doubts were hidden well and a letter from Dad was hugely supportive and full of unconditional parental love. Already my adventure was unleashing emotions that would have probably otherwise remained unsaid and the honesty that resulted from it was hugely moving and very precious.

The difficult bit was sharing my plans at work. The easy answer was to simply leave and the past few months had made that a temptation, but life is rarely so simple. I had a mortgage and bills to pay, and a family to keep fed, warm and healthy during my year away.

I decided to go for the sabbatical option, even though it would mean that I would have to return to an environment that was rather less than enjoyable. But who knew how I might feel after a year away – perhaps the break and a new perspective might be beneficial all round and I could approach another decade with renewed energy and a grander global vision. That ought to appeal to the Germans, surely?

In the business press I noticed several articles where visionary companies spoke about the benefit of holding on to valued individuals and paid them while they went off to recharge. I carefully cut them out and added them to the early-morning rehearsal of words in front of the mirror before the now tedious dash to the train.

I sought out my new boss in his newly decorated MD’s office and put the idea to him across his grey wooden desk. I tried not to hide anything and attempted to enthuse on the energies that the trip would bring. The pieces about sabbaticals that had handily appeared in the press to help my cause delivered a faint glimmer of hope, despite the heavy sighs that dominated the meeting rather too much.

At this early stage in his appointment, it was clear that anything that rocked the boat would be frowned upon from above. The easy option for him was to stay safe and follow the path of least resistance. But, having worked alongside me for several years, he heard a nagging whisper urging him to do better than just dismiss my request out of hand. At the end of the consultation he agreed to think about it for a while, and a couple of days later I was called back for the decision.

Unfortunately, it was the two-letter version.

No.

No, a sabbatical would be unacceptable. The achievements and the market successes, the loyalty and the passion, the desire to come back and continue were all acknowledged, but the answer was ‘No’.

If I wanted to go, then it would set a precedent and everyone on the board would want to be off. While none of my fellow directors had ever previously hinted at the desire to spread their wings and set about discovering new vistas, I had to accept that perhaps they might be tempted.

I felt there was an element of brinkmanship being played. Told no, I might simply dismiss the idea as a dreamy aberration, forget about the magnitude of sailing around the world and knuckle down to drowning every time I pulled into King’s Cross.

If that was the case, it was a complete misreading of my character and the burning desire that was becoming an all-consuming inferno. My mind was made up and, with Clipper assuring me of my place, I was going to be on the deck of that yacht when the start gun fired, no matter what it took. The flickering of the flames could clearly be seen from the other side of the grey desk and the awkwardness that it generated suggested that my single-mindedness was hardly helping make for a perfect corporate day.

‘Nothing changes,’ I told him, hoping beyond hope that Anne agreed. I would resign if I had to, but still hoped that we could work some sort of deal. With my head light from the euphoria of the moment, I walked back to my office and wondered how on earth I might find the money – not just to fund my place, but also to keep the family surrounded by bricks and mortar, heat and fish fingers, petrol and tins of Winalot while I was away.

At least the unhappy meeting had closed with the agreement to give it even more thought, and the man in charge was at pains to point out that he wanted to reach a fair conclusion if he possibly could. But until that could be resolved, he asked me to keep the plans to myself. He did not want the other directors to know and he certainly did not want a boat-rocking session with his superiors from across the water.

That was fine, except when it came to my most immediate colleagues. Not only did I owe it to them to be honest, but the person who would take on most of my responsibilities in my absence was the person I had employed and nurtured for the past five years. She had become a loyal and trusted friend and, quite apart from wanting to ensure that she was happy to enter the lion’s den, I wanted to be completely straight with her as I planned my own future.

I organised lunch and nervously told her that the world’s oceans awaited me. She had seen me struggle in recent months and had been supportive in the increasingly lonely battles, so was well placed to appreciate why I wanted this dramatic change. And while I gabbled on about what a great opportunity it was for her career, she stopped me short, held up a hand to attract a passing waiter’s eye and ordered two glasses of champagne.

While the company decided how it was going to see me on my way, I took out an additional loan on the house in order to pay my £23,000 crew member’s bill, hoping beyond hope that the future would deliver a solution to fund it all.

After several more months we finally agreed on a package that would allow me to leave but generously acknowledged my length of service and contribution to the company. My position would be made redundant and the resulting deal would provide enough funds (with careful housekeeping) to keep Anne and the children housed, fed and warm for my year away. The dog might have to get used to the cheaper offering of Sainsbury’s own brand of diced rabbit in gravy, though. And despite the supposed secrecy, by the time the announcement was made, the entire company knew all about my plans.

By then I was sporting the giveaway skin colour of a man who had spent several weeks at sea with other like-minded volunteers likewise completing their training. More telling than the healthy skin tone was the healthy persona that went with it.

The dark-rimmed, sunken eyes. The close-to-the-surface anger sparked by political games. The bubbling frustration caused by a surfeit of meetings in too many different locations with not enough time between them. The daily backlog of a hundred e-mails and mailbox messages. The ever-ringing mobile and the stream of urgent faxes that drove the breakneck pace of an average day. All of that had blissfully disappeared for a few precious days as I faced my new future and loved what I saw.

The issues that seemed so important had folded themselves up and found a tiny recess in my mind where they remained wonderfully undisturbed. With them went the nine-to-five routine of commuting, the familiar London streets that marked the route between station and office, the sandwich bar with its unchanged lunchtime menus and the ongoing tedious exchanges between one department and another.

All of this had been replaced by the growing camaraderie of a bunch of strangers who arrived, from a broad mixed bag of backgrounds, at the quayside, intent on giving nothing less than their all.

Every applicant for the race underwent an identical training programme and no matter if it was a crew member’s first, tenth or one-hundredth time on a boat, we were all starting as equal. I was amazed at the numbers who had no sailing experience at all yet threw themselves at the course with real gusto.

The training was designed to be as tough as possible, but the harder the instructors made things, the more inspirational the performance from this unique group of people. No matter whether it was three in the morning or three in the afternoon. No matter whether we were soaking wet, tired or confused. No matter whether someone was making a lunge to the rail to be gloriously sick in front of the rest of the crew or making a fool of themselves by cocking up a manoeuvre. The only thing that existed on board was a committed level of support and a desire to help each other through whatever surprise came next.

A larger-than-life gynaecologist, used to the high proportion of teenage mothers Newcastle produces, would break off her conversation, lean over the side, throw up, make a typical nurse-like comment about lunch being just as good on the second tasting, laugh enthusiastically and then look for the next job to do. Down below, three university students sat in a line, looking for all the world like the three wise monkeys. With impeccable manners, they politely asked if perhaps the bucket might possibly be passed down to them, before burying their head and adding to the content. The retching sound from one would set off his neighbour, while the third, rather than simply letting supper go on to the deck, would make a polite request for the bucket to be passed on in readiness.

Through sail change after sail change, working twenty-four hours a day with just a few hours of snatched sleep, we pounded through the waters of the Atlantic until we were exhausted. Exhausted from the physical exercise, exhausted from the vomiting, exhausted from the amount of information we were being bombarded with and exhausted from the lack of a full night in a stable bed.

Yet, exhilarated and completely alive too, alert and more awake than I had been in years, I was inspired by the supporting, laughing, encouraging help that lifted moods and got us working together as one. Strangers became brothers and by the time we set foot back on dry land, the group had become a really unified team.

Social barriers vanished and I was deeply, deeply inspired by the generosity of the personalities I shared my training with. After just one week, I knew without a shadow of a doubt that I had made the right choice and, with life looking far less jaded, I returned to the office with a definite spring in my step.

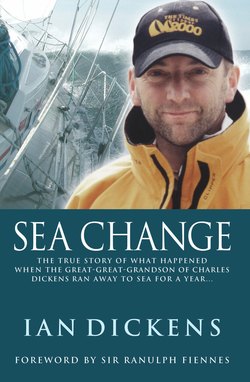

I was humbled once more, but this time in the corporate world, as my day of leaving drew closer. After so long with one company I wondered if I might suddenly crumble in an emotional heap when the moment came to say goodbye. Setting that process in motion, I had written to all the contacts that filled the bulging pages of my Filofax, from Ackerley via Lichfield to Young. I had been amazed at their responses, which ranged from the ‘I always knew you were barking (Ackerley, A.) to ‘Wow, what an adventure – you’ll be following in the steps of my great-great-great-grandfather (Lichfield, P.) to ‘What a sad day for the company and what a great moment for you’ (Young, R.). I was applauded for my decision to think big and brave, rather than make the more predictable step of safely sidling from one desk to another, and congratulated for taking a dive into the unknown.

Much of this sentiment came from individuals for whom I had a huge respect, having followed their own adventures with ill-concealed envy via e-mails, postcards and letters dispatched from an exotic collection of foreign fields over the years. Chris Bonington and Ran Fiennes urged me onwards and upwards. Mirella Ricciardi, the artist behind the seminal photographic book Vanishing Africa, grasped my decision with a passion that was frightening. Judy Leden, the women’s world hang-gliding champion, wrote a dedication in her book encouraging me to ‘go on taking risks’ and giggled down the phone when I told her I was. Adrian Thurley – another pilot, ex-Red Arrows – was equally thrilled at the prospect, as was the company president, who wrote a personal letter of warm support from his eyrie high up in a glass tower in the Shinjuku district of Tokyo.

If these responses were humbling, the icing on the cake came in August 2000 – a couple of months before the start of the race, when I was asked out to dinner by my advertising agency. We met at Kettners restaurant in Soho and it was clear that something was up. Jeremy Bowles, our account director, was full of over-the-top innocence and bonhomie. Sarah Gold, our account handler, could barely conceal her excitement and my work colleague Sara, who was set to inherit my day-to-day problems, puffed nervously on more cigarettes than usual.

These people had kept me sane for the past year as we fought our advertising battles and they were all trusted friends. Despite my agency’s reputation as one of the most creative in Europe, the most imaginative nicknames they had managed to create for each other were ‘Bowlsie’ and ‘Goldie’.

Bowlsie and I had worked together for twelve years and had been thick as thieves through all of them. Not only had we worked hard to create a whole series of award-winning campaigns, we had played hard too.

Given such a close bond, I guessed that Kettners was not going to be a quiet drink and an early night, but was still unsure what their nervousness was hiding. After a studied yawn from Sara and yet another whispered conversation on her mobile, it was suggested that perhaps we might move on to Groucho’s for another drink.

Rumbled.

I knew that none of them was a member and the club has a distinctly superior attitude to visiting guests. I knew this because Bowlsie and I had been kicked out a couple of years previously for daring to use a mobile phone from the club’s dining room. It was apparently strictly against the rules.

Once in the club, my posse of friends urged me up some back stairs and then, rather curiously, shoved open the door of the Gents and pushed me in. The curious part was that they followed – girls as well as boy – and then started to undress me.

I had a panic-laden vision of being pushed naked on to a stage where a series of strippers would set about humiliating me as my mates cheered. It was not something I really wanted to endure and a good scuffle in the confines of a pair of urinals ensued. In between breathless lunges, they promised that nothing untoward was about to happen. They just wanted me to wear something a little different for whatever awaited me in the club.

Out from a suit bag came the outfit of a Royal Navy ordinary seaman, circa 1942, and as my suit, shirt, trousers and tie were stuffed away, I was transformed into a jolly Jack Tar with huge bell bottoms and jaunty cap.

Dressed as a sailor out for an evening in deepest, gayest Soho. Ha, bloody ha!

I was led to a door and, amid a lot of stage coughing and banging, it swung open and I was pushed through, to be greeted by a great cheer.

I stood, mouth agape, taking in the scene in front of me. I had anticipated that there would be a bit of a work send-off and had expected to see familiar faces from my office, the agency and one or two other companies I worked closely with. What I hadn’t expected was the breadth of the turn-out and the generosity that such a commitment involved.

As I scanned the room, I could see photographers David Bailey and Bob Carlos Clarke. Alongside them were Richard and Susan Young, Jane Bown and Barry Lategan, chatting amiably with Carol White, head of the Elite Premier model agency. Judy Leden (who hates coming to London from her Derbyshire home) was there, as was Charlie Shea-Simonds, leader of the Diamond Nine Tiger Moth display team. There were Damon and Georgie Hill, giggling at my outfit, mingling with Ron Smith, who had come up from the Isle of Wight especially for the night. By the time he got home it would be way past midnight. Mountaineer Paul Deegan was there; so was TV presenter Chris Packham. Everywhere I looked, I saw the faces of people I had worked alongside over the years, and they all had happy, smiling, laughing faces, genuinely pleased to be able to share the moment.

There were speeches, of course, and as I stood on a chair I spotted more and more precious people who had made time in important schedules or travelled long distances to say goodbye. I was truly humbled by what I saw and taken aback by such simple and genuine signs of friendship. It meant a huge amount to me and I was moved to tears by such kindness.

The party flowed and everyone seemed to have a great time as I went from hug to kiss, handshake to embrace, toast to banter and back to hug again. One hard-boiled ad man said goodbye with tear-filled eyes, clearly expecting me to be washed overboard somewhere far away, and saw this as the last opportunity to say a proper farewell.

It was a fantastic night – especially as Anne had been smuggled into the club (thank heavens the stripper fear had been unfounded) and she was as touched as I was to witness the generous outpouring of support that filled the room.

Perhaps I had become too close to the job and, as it became an all-enveloping task, I had been unable to stop and appreciate the numerous good qualities of the people around me. That extended to my family as well, and the exhausted and drained father who sat silent in front of a large glass of red wine at the supper table every evening, too tired to speak or truly listen to the playground news that was being shared with him, had clearly missed so much.

Bugger. Maybe I was wrong to leave after all.

Too late. The deal was done, the letters written, the lawyers happy, the Germans ecstatic, the President sad and I guessed that my still-warm seat had designs already on it.

If the sole result of my decision was to witness such honest declarations of support, then that alone was already enough, even if the race itself were to turn into some sort of ghastly nightmare. The leaving party had been a bit like attending my own funeral, where I could look down and witness the people I care about, saying all the nice things that the pressure of everyday life normally holds back.