Читать книгу To Be Someone - Ian Stone - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Three David Watts

ОглавлениеI attended JFS (the Jewish Free School), a co-educational comprehensive secondary school with 1,500 kids in Camden, North London. My parents wanted me to go to a Jewish school, so it came down to a choice between that or the much more religious Hasmonean High School in Hendon. Our family had recently moved into a housing association flat in West Hendon, a non-descript area off the Edgware Road. (Two thousand years before-hand, the Roman army would’ve marched almost past my house). My mother had very sensibly turned down the chance of living in a slightly bigger place on one of the most violent estates in London, Chalkhill in Wembley. It would’ve been handy for cup finals but I may not have made it to my eighteenth birthday. West Hendon was a brisk forty minute walk to Hasmonean, but our religious beliefs, never strong to begin with, dissipated through the 1970s and so my parents opted for me to take the bus, train and bus journey to Camden. It was one of the few decisions they made that I agreed with.

Camden was not the entertainment hub that it’s become in the last twenty-five years. Like most of Britain in the late 1970s, there was an air of sleazy decay about the area. The market was vaguely trendy, but this was before enterprising hippies started flying off to India and coming back with cheap trinkets they could sell for 1,000% mark-up to unsuspecting tourists. Mainly because there were very few tourists.

The residents were a motley collection of Londoners. There were four men who lived in the streets around the underground station entrance. We would’ve called them tramps, which at that time described a very particular type of person. (Although there are a lot more homeless people now than there ever used to be, one sees very few 1970s ‘tramps’ any more but they were a regular feature of London life back then.) Men (and it was always men) with matted hair, wearing clothes that they’d not taken off for several years and giving off an odour that would stop a train. Which presumably was why they weren’t allowed on the platform. They didn’t even beg. Most people wouldn’t (and because of the smell, couldn’t) go anywhere near them. I have no idea how they fed themselves but they didn’t seem to be emaciated so they must have been eating. Although it might have been the eight layers of old newspapers they used to keep themselves warm. For amusement, they used to drink heavily and bark – actually bark, like big Alsatian dogs – at schoolchildren as we walked past them. You’ve got to have a hobby. I guess when people look back to days gone by and talk about having to make our own entertainment, this is what they mean.

I never mentioned it to my mother. She may well have regretted sending me to JFS if she knew I’d have to run the gauntlet of barking tramps. The first time it happened, I almost wet myself. The tramps’ barks were very realistic. I honestly felt like I was about to be attacked by an enormous and incredibly malodorous Alsatian. They laughed their hearty tramp laughs and from then on, I was fair game. It happened so often, I was crossing the road to avoid them.

*

Our school was next door to Camden School for Girls, a grammar school that was slowly transitioning into a comprehensive. It was full of impossibly tall and willowy middle class girls with double-barrelled surnames and first names like Vanessa or Chloe or Virginia. They all had cheekbones and good teeth and looked healthy and well-bred and no doubt took part in eventing competitions at weekends. They looked upon us, running around in our playground, with our outsize noses and Coke-bottle glasses, as the aristocracy look upon people who do manual labour. They paid us absolutely no attention whatsoever.*2

Further up the road was Holloway Boys School, a famously tough inner city comprehensive whose alumni include one Charlie George, bad boy striker for Arsenal and one of my earliest heroes. The Holloway boys were a fearsome lot. One imagines that their school reunions would have been decimated by enforced absences due to the actions of the criminal justice system. As well as terrorising any kids who had the temerity to walk past their school just because they happened to live near Holloway, their regular lunchtime entertainment was to wander down the road to our school, stand in the street where we could see them and make gas noises and Nazi salutes. Even writing this sentence is shocking to me. Nowadays, I could see it happening perhaps once or twice before the authorities got wind of what was going on and firmly put a stop to it. This abuse went on for years. It probably went on longer than the Second World War. It happened so often, I think it became part of the curriculum.

‘What have you got today?’

‘Geography, chemistry and double anti-semitism.’

We didn’t take it completely lying down. There used to be abuse flying back and forth across the fence and the teachers would shoo us over to the other side of the playground. They should probably then have had a word with the hooligans, but they were more terrified of them than we were. Except for our history teacher, Mr Waterman. He was already a legend after one fantastic incident during one of his lessons. We were in a classroom on the fifth floor of the main building. He crashed in. He was not in a good mood.

‘Sit down everyone.’

We sat down.

‘I’m going to turn round,’ he said in his distinctive Welsh accent. ‘If I turn back and there is a bag left on the desk, I’m going to chuck it out of the window.’ He then turned round.

Now all teachers have their own eccentricities. Some detest chewing, others cannot stand even the merest hint of talking in class. PE teachers don’t like children. Mr Waterman was famous for having an irrational revulsion for anyone who kept their bag on their desk, so even though we were five floors up, we thought he actually might do something that crazy. We cleared our remaining stray bags from our desks.

He turned back, saw a bag on a desk and stared at us.

‘Whose bag is this?’

No one answered. There was a heavy silence in the air. He picked it up and without a moment’s hesitation threw it out of the window. I did wonder whether an unsuspecting child was taking his last breath before being killed by a bag falling from the sky. That would have been an unfortunate way to go and very likely the end of a promising career in teaching. We all looked at Mr Waterman. Personally, I have never been so scared in my life. No one said a thing. ‘Oh Shit!’ he said and then without warning, ran out of the room. We waited. It was strange. Was the lesson over?

After a minute or two, he ran back in carrying a battered looking case. He was out of breath. He looked at us and said, ‘That was my fucking bag.’ The laughter kept going for a good five minutes. What a man.

Now anyone who, even by mistake, was prepared to throw his own bag out of a fifth floor window, was certainly not going to tolerate Nazis outside the school gate. He was livid. Being a history teacher, he was perhaps even more acutely aware than the rest of us of the cultural significance of sieg heiling at a Jewish school. He was ranting at them.

‘Fuck off, you Nazi wankers!’ he shouted. One didn’t hear a teacher swear that often.

They just laughed at him.

‘There are black kids doing Nazi salutes,’ he said to no one in particular. ‘How the fuck can you have black Nazis?’ It was a fair question.

‘Fuck this,’ he said and ran off. He came back a few moments later armed with a cricket bat, opened the gate and ran straight for them.

‘Come on lads,’ he said. ‘Let’s give the bastards what for.’

This whole episode had taken a turn I wasn’t expecting. I’d been hitting a tennis ball against a wall so I kept hold of my tennis racquet and followed him out. I’m not sure it would’ve been much use in a fight even though I had a decent forehand. But it didn’t matter. The Holloway boys took one look at this wild eyed, cricket bat waving, moustachioed Welshman and ran. It was glorious. They tried once or twice more after that but their hearts weren’t in it. I wish he’d done it earlier on. One by-product was that any lessons he took after that were incredibly well behaved.

Not that I attended lessons that much. I just thought that most of what they were teaching me was nonsense. I wasn’t interested in glaciers or the function of the pituitary gland.*3 By the last year at school, I used to take regular afternoons off. I’d walk purposefully along the corridor like I was rushing to get to my first lesson after lunch. And then when everyone was inside their respective classrooms, I’d scarper. The caretaker often saw me leaving but he never tried to stop me. He nodded imperceptibly, giving me a look that suggested that he thought it showed initiative. Although he might have been thinking that with my attitude, I may end up as a school caretaker.

I’d take a desultory wander round the shops of Brecknock Road. There wasn’t a lot to see unless you liked hardware stores, bookmakers and takeaways. Some of the more grown-up-looking kids would hide their blazers in their bags and venture into the pub or the betting shop. In the pub, there was always the risk of bumping into one of the teachers who regularly drank in there, even when they had lessons that afternoon. I can’t say I blamed them. If I had to teach me, I’d have been drinking as well.

I didn’t have many friends at school. I met Simon and Robert when I was around twelve. They were both in another class, in another house, but we hit it off. They were mates and we got chatting one time in the playground. They were both Chelsea fans but I didn’t hold it against them. Robert had a nose almost as immense as mine but no one said anything to him about it because he was already over six feet tall. He was taller than everyone in the class and most of the teachers. He was the tallest person I’d ever met. I used to go round his house. He lived with his sister and his parents in semi-detached middle class splendour (to me) in the posh part of Hendon. They were all very tall as well. I was impressed. His house had a drive. It had central heating. It was always warm. His mum was very proper but she was sweet with me. She’d make me food and listen indulgently while I chattered away.

Simon was also a couple of inches taller than me, and he was way more confident in his opinions. He was, and still is, one of the funniest mates I’ve got. It’s ever so slightly annoying how quick he is sometimes.

Simon lived in Edgware in a flat with his mum, Carole, and his sister, Jackie. They didn’t have much more money than we did but their flat was more comfortable than ours. Carole was glamorous. She laughed at all my jokes and made me food. I loved going round there.

Later on in life, Simon was the first of my mates to have a car. He was also the one who organised most of the things we did together. The only reason we had a football team was because he used to ring round. I don’t think we thanked him enough. Every friendship group needs a Simon.

In our final year, Simon and I often decided to forgo the delights of double religious knowledge and some cock-and-bull story about plagues or floods and wander down to the centre of Camden instead. We spent half an hour browsing in the Doctor Martens shop by the station. In a side street, there was a film crew shooting an episode of Minder; I was a big fan. Arthur Daley was a truly brilliant character and there was something great about watching a TV show and recognising locations. There was a crowd of twenty or so people watching it happening, most of them pensioners with nothing better to do. Dennis Waterman and George Cole were discussing the forthcoming scene with a guy who I presumed was the director. He was talking animatedly about what he wanted while the crew waited patiently. It was a nice day so no one seemed to mind.

At some point, the director strode purposefully back behind the camera, put on his headphones and said ‘quiet please’. A hush descended. He then shouted, ‘Action’ and the scene began. Ten seconds after it began, an old lady in the crowd said, ‘’Ere, it’s Richard Burton innit?’

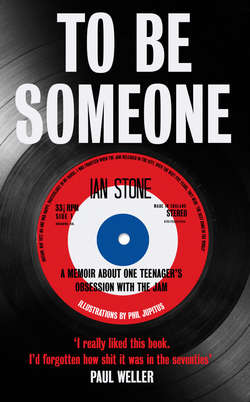

On one of our many afternoons off, we were browsing in the record shop and we came upon the In The City album. Simon told me I should listen to The Jam. He looked serious and he was very insistent but no matter how enthusiastic someone is, it’s hard to convey what a band sounds like without you hearing them. I said I’d check them out, but I guess I never got round to it until John Peel played them on his show. Then the penny dropped.

When Simon wasn’t available for midweek post-lunch trips out of school, I would go to the pictures on my own at my local cinema in Hendon Central. One time, I went to see Eraserhead. My teenage brain was nowhere near ready for the surreality of David Lynch. At one point, I started laughing at a dead chicken dancing on a stage. The man in front of me tutted loudly presumably because the film was making a serious point I’d failed to grasp. Forty years later, I still don’t understand what the fuck that point might have been. I also saw Capricorn One, a film about a shadowy government agency that faked the Mars Landings. I was getting a decent education but not in core curriculum subjects. I went to see Rocky and ran all the way back home from the cinema shadow boxing. For a moment, I contemplated a career in boxing. I mentioned it to my grandmother. She started laughing and said that my nose was too much of a target. She was right.

There wasn’t much I engaged with at school but I liked PE. I never bunked off for that. I was physically capable, no mean achievement in a Jewish school where some of the kids could barely walk ten yards without feeling faint. I was a very fast runner, something that had come in handy when I was trying to escape the attentions of the Holloway boys. I ended up running the one hundred metres for my school house along with a boy called Adrian Grant. Adrian was the most accident prone boy in the school. He had a briefcase that regularly fell open for no reason; once it did so at the top of the staircase and spilled its entire contents five floors down the stairwell. I can still hear his plaintive ‘Oh no!’ as it happened. In Chemistry, if he was handed a Bunsen burner, we’d all step back a couple of paces. He’d catch his blazer on a door and rip the pocket. If he was using a compass, it would end up in his leg. He once wet himself in class.

We lined up at the start of the race, the gun went and we hared down the track. When I crossed the line, I turned round to see where he’d finished. Adrian and another boy were having a fight halfway down the track and the games teachers were running towards them to break things up. One of Adrian’s plimsolls had come off halfway through the race, he’d stumbled and taken down the boy next to him. I wish I’d seen it happen.

I never learnt to swim, though. I was following a long tradition of Jewish non-swimming. There’s not a lot of call for swimming ability when you’re wandering about in the desert for forty years. Even when we did get to the seaside, we’d only go in when God had parted the waves. My ancestors really didn’t like swimming. As a child, the water was not my friend. I had hundreds of swimming lessons but it never took. Sometimes, it was the teachers. Mr Duncan, my angry PE teacher*4 standing on the side of a pool shouting ‘Swim for goodness’ sake, swim’ was seen as a viable teaching method. Whereas one can’t imagine a driving instructor standing on the pavement shouting at a learner passing by ‘Drive for goodness’ sake, drive!’

Both my parents and my sister being non-swimmers didn’t help. Their abject terror of any water above chest height may have affected my ability to relax in the water. I was OK splashing about in the shallows but anything above my waist and I started getting the shakes. If a tsunami had hit West Hendon, our family almost certainly wouldn’t have made it.

All of the above does make it odd that Mr Duncan, for reasons only known to him, chose me to race for Weitzman House in the school swimming gala. I suggested to him that perhaps there might be people who could actually swim who were more suitable for the race. But Mr Duncan, like most PE teachers I’ve met, was not a listener. So it came to pass that I found myself lining up in the middle lane of the school swimming pool for the twenty-five-metre front crawl. Not only could I not swim, I couldn’t dive in either. I was, as you can imagine, terrified.

The whistle went, I shut my eyes, belly flopped into the water and started thrashing my way across the pool. Luckily, we started in the shallow end and every so often, I was able to stop thrashing, stand on the bottom of the pool, take a breath and then push off for another five metres of thrash. But at some point, I knew that I’d be in the deep end and putting my feet down wouldn’t be an option. About halfway along, I stopped, felt my tip toes hit the bottom, took a big gulp of air and then resolved to thrash until I touched a wall. Which is what I did. It felt like it took forever but I finally felt the comforting edge of the swimming pool. When I came up for air and looked either side of me, I was a bit puzzled to find that none of the other swimmers appeared to have finished. I thought I’d won. I looked up and there was Mr Duncan.

‘What the fuck are you doing you fucking idiot?’ he said.

I didn’t understand the question.

‘Why are you over here you moron?’ he asked and it was then that I properly looked around and realised that I’d swum in a semi-circle, across all the other lanes and was on the side of the pool. The only good thing was that I was so slow, the other swimmers were well past me by the time I veered across their lane.

‘Sorry sir,’ I said. I was just glad to be alive.

I wasn’t chosen for the swimming team again. But Mr Duncan had to do something with me, so during the next swimming gala, he got me to help out with the timings. I was much happier on the side of the pool watching Miss Honeyman get the kids lined up for the start. I tried not to stare at her legs too much but it was distracting. So much so that I missed the start of the senior boys one hundred metre front crawl final. I only pressed the stopwatch around halfway into the race. Stephen Franks won the race and Mr Duncan came running over holding his clipboard.

‘Time?’ he barked.

I knew that Stephen had taken longer than twenty eight seconds to swim one hundred metres. I quickly guessed a time.

‘Fifty six seconds’.

Mr Duncan duly noted it down. He looked impressed. He had every right to be so. It was only six seconds outside the world record. Slightly surprising for a fourth former at a comprehensive in Camden.

In 1978, a few years after I joined JFS, The Jam released ‘David Watts’ on what was then known as a double A-side single with ‘“A” Bomb in Wardour Street’. Aside from being insanely catchy, I also found it funny. I wasn’t what you’d call a star pupil and I was under no illusions that I could’ve been in any way like David Watts. The school team was unlikely to have me as their captain, I wasn’t going to pass all my exams and I had no expectation of being made head boy. I didn’t know any of the girls in the neighbourhood and even if I had done, none of them would’ve been the least bit interested in me.

This was another example of The Jam introducing me to other bands. It wasn’t like today, where sophisticated algorithms on Spotify or iTunes will see you listening to one band and suggest that you might fancy listening to something similar. In the 1970s, unless you had older siblings or parents who might take an interest, you had to find out for yourself.

I remember buying this single. It had the coolest cover I’d ever seen with arrows pointing in two different directions. When I took the single out and had a look, I wondered ‘Who is Ray Davies?’ This led me to The Kinks and ‘Waterloo Sunset’ and ‘Apeman’ and a hundred other tunes. In turn, they led me to Small Faces and hearing that keyboard intro on ‘Tin Soldier’ (Paul’s favourite track on Desert Island Discs). Because of Paul Weller, I’ve been listening to that song for forty years. It’s very much appreciated.

My parents, focused as they were on their own needs and desires, took very little interest in my schooling. My dad left school at fourteen, my mum at fifteen, so they had very few expectations about what education could achieve. My mother got me up and out of the house in the morning, and after that I was on my own. She’d read my school reports, tut at regular intervals and then hand them back to me without a word. As for my dad, I don’t think I had a single conversation with him about school. He went to work before I left and came back after I’d got home so he had absolutely no idea what I was up to all day. I think he knew that I went to school but I could’ve spent my days BASE jumping off tall buildings and he’d have been none the wiser.

If my children were half an hour late in the mornings, we’d get phone calls from the school secretary asking politely about their whereabouts. After an hour, the calls would be less polite. If they missed a whole morning and we hadn’t notified them, the authorities would be involved. Whereas if I didn’t turn up to school on a Monday, the chances of my parents hearing about it in the same week were minuscule. I think I could’ve left school at fifteen and it’s possible no one would’ve noticed. I wish I’d tested the theory.

The only time my mother really got involved in my school life was when I was suspended. It happened twice. The first time, I was involved in a fight with a girl in the fifth form. I was in Year Seven (eleven years old) and I was on the small side. She was fifteen and she was the biggest girl in school. She scared the living daylights out of everyone, including the teachers. I was walking down the corridor one afternoon when I saw her coming towards me carrying a big pile of books. I found this surprising. She didn’t strike me as a reader. She dropped one of the books and tried, without success, to pick it up without letting go of the others. I tried to make myself as inconspicuous as possible but she caught my eye.

‘Oy. Come here. Hold these,’ she said. It wasn’t a request.

I took hold of the books. She bent down to pick up the other book and I was confronted with the biggest arse I’d ever seen on a living human. It was too tempting. For reasons I still don’t entirely understand, I kicked it very hard and she went sprawling across the corridor. There was a boy standing opposite me and I can still remember the look of utter amazement on his face as he watched what I did. I didn’t wait around for her to get up. I just dropped the rest of the books, turned and ran.

She moved remarkably quickly for her size and as I scooted round the school, I could hear her pounding down the corridor behind me.

‘You’re fucking dead.’

I had no reason to doubt that she meant it. I ran across the playground and into the main building. She seemed to be gaining on me; I could hear her breathing. I ran into the boys’ toilets, found a free cubicle and locked the door. I was safe. She wouldn’t dare cross the threshold and even if she did, she’d be halted by the Fort Knox type security of my cubicle door. She didn’t even hesitate. I heard her crash into the boys bogs and two seconds later she broke down the door and beat me up in front of an amazed crowd of boys who, sensibly, did nothing to help me. I put up very little resistance. I just curled up into a ball and waited for it to end. A male teacher appeared shortly afterwards and dragged her off me. We both got suspended for a week for fighting and she got an extra day for breaking the cubicle door. We got on quite well after that. I don’t think she could quite believe what I’d done. She thought it was ballsy.

I was always talkative. I enjoyed getting laughs. As an adult, I’ve built a career on this nonsense but at the time, it got me into serious trouble. I insulted our Hebrew teacher Miss Felberg by loudly proclaiming, when I thought she was out of the room, that learning Hebrew was a complete and utter waste of time. She was in the store cupboard, and came out raging, looking directly at me.

‘Did you say that?’

Even in my first year, I had something of a reputation. I saw no point in denying it. ‘Yeah’.

‘Why do you think it’s a waste of time?’ she asked.

‘Because it is,’ I said, not giving her much to work with.

‘I think you should apologise to me and also to the rest of the class who are all interested,’ she said.

I got up and stood at the front of the class. I looked around. I knew for a fact that no one was any more interested than me.

‘I’m sorry . . .’ I said. A long pause. ‘. . . that you have to learn Hebrew.’

There was a big laugh from the class. It felt good. Miss Felberg, however, was not laughing and threw a blackboard rubber at me. It swooshed past my head and clattered into the wall behind me. I was watching a lot of cricket at the time and I thought that she had a decent throwing arm. I decided that if it ever came to it, I would not risk a quick single if she was fielding.

‘Come with me,’ she said ‘We’re going to see Mrs Abrahams.’

This was not what I was hoping for. Mrs Abrahams had a fearsome reputation. She believed in discipline and God. I had no interest in the first one and I was rapidly losing faith in the second. I was well aware of her temper. I was used to adults shouting, but usually it was at each other. I wasn’t looking forward to having her considerable ire directed at me.

We went to her office. Miss Felberg told me to sit down while she informed the secretary what I’d said. The secretary didn’t laugh, which made me think that Miss Felberg had told the joke wrong. The secretary took Miss Felberg into Mrs Abrahams’ office, and I heard them having a short chat. Miss Felberg emerged and then harrumphed off without giving me a second glance. I waited.

Time passed. I looked around, tried to think about other things. At one point, I started whistling. The secretary stared at me and I stopped. I waited some more. After a time, Mrs Abrahams popped her head out of the door and indicated that I should go in. She was dressed immaculately. She was attractive but in the way that made it perfectly clear that any thoughts in that direction were to be redirected elsewhere. Aside from her face and hands, there wasn’t an inch of flesh on display. Her clothes were beautifully made and her hair was perfect. She was shouting as I came in.

‘This is a Jewish school’.

She pointed at the mezuzzah (a small scroll attached to doors in Jewish homes and places of work; the person passing through the door is meant to touch it and kiss their hand as a show of devotion to God) on the door. Just in case the fact that the school was called The Jewish Free School and all the men had to have their heads covered and we spent thousands of hours being taught Hebrew and Old Testament religious knowledge were not enough in the way of clues.

‘We teach things that will make you better able to contribute to the Jewish community. And one of those things is being able to speak Ivrit [the Hebrew word for Hebrew]. Do you understand?’

I didn’t get a chance to answer either way.

‘A waste of time?’ Her voice got louder. ‘Why would you say such a thing to Miss Felberg? How could you say that learning Ivrit is a waste of time? Who are you to decide what is and isn’t a waste of time? That is an insult to the other pupils, to the teacher, to me, to the school.’ She paused. ‘To Israel.’

I suppressed a laugh. I was imagining people in Tel Aviv phoning each other:

‘Did you hear what Ian Stone said?’

‘No.’

‘He said that learning Hebrew is a waste of time.’

‘What? The little prick!’

She moved round the desk and came up very close to me. It was like the scene in Alien where the monster gets really close to Sigourney Weaver. Apparently, I hadn’t completely suppressed the laugh.

‘Why are you laughing?’

‘I’m not laughing’ I said, while sort of laughing.

She was really shouting now.

‘Your gross disrespect for our teacher and the language is disgusting’.

‘Christ. Keep your hair on,’ I said.

*

Later on, when I relayed the conversation to Simon, he started laughing and continued for about a minute and a half.

‘You fucking idiot,’ he said. ‘She was wearing a sheitel.’

‘A what?’

‘A wig. Religious Jewish women shave their heads and wear a wig.’

‘What? Why? How do you know this?’

‘My mum told me. A man is not to look upon a woman’s hair. It says it in the Torah.’

‘Where?’

‘I don’t know. In the hair section.’

‘I don’t understand. Why can’t they look at a woman’s hair?’

‘Because it will drive them wild with desire.’

‘Hair?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Fuck off.’

‘I’m telling you. She must’ve hit the roof.’

We were both laughing now. ‘She did.’

That was one of the few days at school where I actually learned something. At the time, in Mrs Abrahams’ office, I didn’t understand any of this. All I could see was her going bright red. I’d never seen anyone go that red. She looked like she wanted to hit me but by the mid-1970s, that sort of schooling was being slowly phased out so she just glared at me for a short time and then took me to see the headmaster.

We trooped over to his office and when he was told, he was, if anything, more apoplectic than her. He ranted for a while and I stopped listening. He was almost always ranting about something, generally to do with not wearing our skull caps. I concentrated on his dandruff. He favoured a black suit with a black cape, so it was always noticeable, but it seemed particularly bad today. As he spoke, I could see it falling off his head like a moderately heavy snow shower. Like it might settle. It piled up on top of the dandruff already there. His shoulders looked like a ski resort. He told me to go home and he would speak to my mother in due course.

And so it was that I had a week off school. It was incredibly boring. Today, with all the different TV channels and Xboxes and the like, I could’ve kept myself busy. Back then, there was nothing to do. One of the only things stopping us bunking off more than we did was the almost complete lack of entertainment available at home during work hours.

I watched Pebble Mill at One. This was a magazine show broadcast at, would you believe, one o’clock in the afternoon. It was broadcast live from Birmingham during the week and was very popular with students, the elderly, the bedridden and people who were snowed in. The audience was entirely made up of old people. The women all had white hair, most of the men were bald.*5

My mother was really upset with me because she had to take a week off work. I didn’t take a lot of looking after but without her, I wouldn’t have eaten. She made me food, knocked on my bedroom door to tell me it was ready and told me to turn the music down. It was like having the angriest room service ever.

The following Monday, she had to come in and sit with me in the head’s office while he laid into me again for what felt like a week. He was shouting and spitting. One small bit of spittle landed on my mother’s bag. All three of us saw it happen but no one said anything. As we were leaving, he made it very clear that if I ever said anything else grossly insulting to the Jewish faith, I’d be expelled. Did I understand? I did. I almost said something grossly insulting there and then, just to get it over with.

*2 Except for Martin Cohen, who was a very good-looking guy. He told me one day that he’d started going out with one of the girls from Camden Girls School. He was meeting her later on and did I want to tag along. Later that day, Martin and I got the bus to the station and in order to look like he didn’t go to our school he took off his school blazer and tie when we got there. Vanessa or Chloe or Virginia turned up shortly afterwards and they kissed. I was introduced. She gave Martin a look that said ‘what are you doing hanging out with one of those kids from the Jewish school?’ It was a fair question. I went home shortly afterwards.

*3 Simon told me that in his Biology ‘O’ level exam, one of the questions was ‘Why is the pituitary gland known as the conductor of the orchestra?’ And he answered ‘Because it looked like Andre Previn.’ Still tickles me.

*4 Was there any other kind?

*5 Twenty-five years later as a fledgling stand-up comedian, I was offered a slot on the show. Because it was live, daytime TV, the producers required a full script of the act you were going to do so as not to offend the delicate sensibilities of the daytime crowd pottering about at home. I faxed (!) the script over and an assistant called me straight back.

‘You can’t say arse.’

‘Can I not?’ I had a joke where the punchline was ‘right on the arse’ and I was hoping I could get away with it. Apparently not.

‘No.’

‘Oh. How about bum?’

‘Hang on a minute.’

He put the phone down on the desk and I hear a muffled shout across the office. ‘Can he say bum?’ There’s a pause. I don’t hear the reply. The assistant comes back on the line.

‘Bum is out.’

‘Oh. Bottom?’

‘Hang on.’ We go round the same routine again.

‘We’d rather you didn’t.’

‘Bottom? Really?‘ And I want to say, ‘Who’s watching this show? Nuns?’ but I refrain.

The assistant has an idea. ‘You couldn’t say rear end could you?’

‘Rear end?’

‘Yeah, rear end.’

I think about it. The punchline ‘right on the rear end’ does have a certain alliterative quality.

‘Alright then.’

I imagine a rubber stamp bashing down on the script. Approved!

A first class return ticket to Birmingham arrived on my doorstep and I travelled up on the day. The audience was not really my target demographic. ‘Right on the rear end’ was met with complete indifference as was everything else I said. It was the worst death I’ve ever had on or off TV. The old people stared at me for my allotted five minutes and the only solace I can find is that they’re all long dead by now. When it was over, the presenter said ‘one more time for Ian Stone’ and got absolutely nothing from them. I still think ‘Arse’ would have got a laugh.