Читать книгу The Shallows - Ingrid Winterbach - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Seven

ОглавлениеLate summer turned to autumn. It rained. It gradually got cooler. Two days a week he was at the art school. The rest of the time he spent in his studio. It was not a space that he much liked, he was renting it temporarily, he’d have to start looking out for something else. He was working on figures that he carved from wood – simple, stylised figures, with strange heads: sometimes of animals, sometimes of humans. Sometimes standing, sometimes kneeling, with exaggerated genitals. Sometimes even with tails, grinning, with grimaces. It had been quite a few years since he’d last painted, only carving, and drawing. He was booked at his gallery for an exhibition the following year.

In the weeks after Charelle’s epileptic seizure Nick got into the habit of cooking supper for the two of them at least twice a week and often also over weekends. He quizzed her about the guy who’d threatened her. No, she said, he wasn’t stalking her any more. She hadn’t seen him for a long time. She didn’t know where he was hanging out nowadays. But with him she could never be sure – he had a weak character. What did she mean? he asked. No, it wouldn’t surprise her if he had criminal tendencies as well. She’d seen it coming from far away. Ever since school. Nick didn’t notice any more suspect motor cars in front of or in the vicinity of the house, and there was no repetition of the swearing incident.

It was quite a bit cooler by now, and he found the evenings with Charelle cosy in the warm, steamed-up kitchen. He started to look forward to these occasions. He took trouble over the food. He thought she was gradually getting to feel more at ease with him. He found her sharp, witty; the more comfortable she got with him, the more she dared – he teased her about the devil, and she teased back. He found her pretty. Uncommon, with the slender wrists and the dense, warm hair. Although she wasn’t his type, he found her sexy. She started cautiously questioning him about his life, about his work. He didn’t reveal much. A bit about Isabel. About the trip to New York. He told her what he was working on, but didn’t take her to his studio. Perhaps later. He was cautious. When she needed a book, he sometimes brought it from the art school for her. She told him about her childhood and about her schooldays. When she was ten, they’d moved to Veldenburg, her father had found a better job there. When she started taking photos at the age of fifteen, she wanted to document everything around her. She photographed the young people in the township, outside the town. She photographed things at random, like people’s back yards, and the food on their tables, everything that caught her eye. She liked taking photos in the cemetery of all the new graves being added every day. And of the pregnant girls standing with their arms around their friends (never a father in sight). And of the young mothers with their babies – the girls that she felt sorry for, because once they had a child on the hip, that was the end of their lives. She was twenty-three. (Older than she looked.) She’d worked in the town for a few years to earn money before coming to Cape Town. They often talked about art. It was going well for her at the art school. She was glad she was doing the course. It had been a good decision. She also liked her room very much. She’d never had so much space to herself, she said again. Sometimes she felt guilty about that, but she wasn’t complaining. She’d thought she’d outgrown her epilepsy – she’d stopped taking medication for it a long time ago. She’d been so ashamed, she said, after he’d come across her that day. No, he said, no, that she should never feel. He hesitated to ask her whether she’d ever been in a serious relationship. He was scared she’d take it the wrong way. But she did once volunteer the information that when she’d had a relationship with someone after school the guy who was stalking her now had been bitterly jealous.

She told him how miserable she’d been the first few weeks in Cape Town. How she’d missed her parents and the familiar surroundings of the village. Obs had felt dangerous, the little streets were so narrow. She’d never known from which direction she could expect danger. In Main Road and everywhere the non-stop hooting of taxis had rattled her. The mountain she’d only later started to find beautiful. But she still preferred the West Coast and surroundings.

Isabel was always present, when he and Charelle were having supper in the kitchen. Naggingly, under the surface – always just outside his field of vision, just beyond his sphere of consciousness. He considered making a statue, a kind of harpy-like figure, with the body of a bird and the head of a woman, balancing on the edge of a bowl, or a dish, in which his head, the size of a hen’s egg, was displayed.

Apart from his sketchbooks, in which he drew every day, he started working again on large sheets of paper of 150 x 110 cm each. In his drawing books he drew little elongated figures, figures on fire, figures with chopped-off limbs, with pig’s snouts, skull-like heads, comic-eyed heads and bulging cheeks, sideburns – all distorted in some way or other. He drew skulls and crosses, coffins, glowing coals, flames and demons – all the props and paraphernalia of hell – inspired by their medieval depictions. But on the large sheets of paper he did not distort the figures. On a large, barren plane he drew a multitude of male figures doing violence to one another in various ways: shooting, beating with sticks, burying, suffocating, torturing, hanging and sometimes even executing. Not a tree, shrub, plant or blade of grass on this vast plane, only the men violently harming one another, in every conceivable manner.

Sometimes in the late afternoon, after working in his studio all day, he had a beer with Marthinus. Marthinus often invited him to watch DVDs at his place in the evening, but Nick accepted only on those evenings he wasn’t cooking for himself and Charelle. He and Marthinus watched, among others, Aguirre, the Wrath of God (with crazy Klaus Kinski – evidently one of Marthinus’ heroes). They watched a few classic masterpieces of Japanese cinema. Woman in the Dunes and Ran made a great impression on him. The first of these he had seen before, but for some reason he found it painful to watch it now. It was something to do with the texture of the woman’s skin. For days he was still under the spell of the atmosphere of the two films. Afterwards Marthinus usually had a fair amount to say about the DVDs. An intense man, who reacted enthusiastically to everything that interested him.

The parents of Karlien, the student doing the satanism project, came to see him one morning. The mother was small, blonde, sexy, tanned, dressed in riding gear. Luxuriant eyelashes, lavish mascara. A trophy wife? The father looked familiar to Nick, some big-shot businessman. He was wearing a sports jacket and smelled of liquor, at eleven o’clock in the morning. The mother did the talking. The father looked bored, checked his watch every so often. They were concerned about Karlien. They did not like the idea that she was meddling with satanism for her project. They didn’t think it was a healthy interest. They thought it might lead her astray. Art was her life, it was her dream, the great interest in her life, apart from horse riding. And her little dogs. She was determined to make it in the world of art. (This was news to Nick.) They were concerned about her, because at home they could still keep an eye on her, but she’d moved into a flat in town with a friend a while ago. Nick didn’t know how to respond. The mother looked pleasant enough, but the father looked like a real bastard. The sort who thought art was a waste of time.

*

Charelle told him one evening about the first day she arrived in Cape Town two years ago. She’d got a lift from Veldenburg with somebody, it was cold in the early morning when he dropped her in Cape Town. She’d had bad period pain (Nick was wrong-footed by this intimate disclosure), and she was scared of the mountain. She didn’t want to look at it. The mountain was everywhere. She’d be staying temporarily in a friend’s room in a house, until she found her own place, while the friend was overseas. The domestic had let her in. She’d told her to wait in the kitchen. Later she’d heard someone come in. The person went into one of the front rooms, closed the door, and started crying bitterly. She’d remained sitting aghast at the kitchen table. Later the girl had come out and joined her in the kitchen. Her parents’ dog was dying, she said, and made them both tea.

Nick was cautious at all times. Not a word, not a gesture that could possibly give her the wrong impression. He was careful never to say too much about himself. He kept his distance. It was only in the kitchen that they were ever together – never in any other place in the house. The single exception was the day she had the epileptic seizure, when he’d gone into her room. Sometimes the woman with the turban came to pick her up for the weekend, and once or twice she visited her parents in Veldenburg. She always informed him when she was going away for the weekend.

*

One Saturday morning in mid-April Marthinus knocked at his door at the crack of dawn. He was wearing a woollen cap and an army overcoat. He blew on his hands and stamped his feet. It was a cold morning. Nick glanced over his shoulder, half expecting to see a pig at Marthinus’ heels. Nick invited him in. They sat at the kitchen table. Nick made them some tea.

‘Did you see?’ asked Marthinus.

‘What?’

‘The news.’

‘No, what?’ He hadn’t watched television for a long time. (Of late too busy preparing food in the evenings.)

‘A failed assassination attempt on a businessman in the Moorreesburg vicinity. An unknown man and three other people are under suspicion. The police are searching for them.’

‘So? Nothing out of the ordinary there.’

Could he smoke?

Sure.

‘No, not at first sight!’ said Marthinus and blew out the match. (What an animated guy this was. He reminded Nick of a cousin of his, the son of his father’s eldest brother. Always full of bright ideas.) ‘No, but wait for it – the other three people are psychiatric patients on the run!’

‘So?’ said Nick.

‘I have a hunch Victor Schoeman has a hand in this – mark my words!’

‘How can you say that?’ asked Nick, astonished.

‘Not your common or garden businessman – he’s also an art collector. The plot thickens!’ exclaimed Marthinus.

‘In what way, Marthinus? I don’t see any plot here. I see only a couple of coincidences.’ (Would Charelle be up by now? He’d not heard anything. She might be shy to come into the kitchen if she heard there was somebody there. He’d not heard her come in the night before. But he’d also been out for a while.)

‘Victor left England under suspicious circumstances. An issue with a creditor or something of the kind. He’s in financial straits,’ said Marthinus, ‘and he has an art background.’

Nick wondered whether Marthinus hadn’t perhaps been watching too many DVDs. ‘How do you know all this?’ he asked. ‘Besides, Victor has always been in financial straits, ever since I’ve known him. That’s nothing new either.’

‘A friend of Alfons’ is in touch with someone who is in touch with Victor.’

‘That still doesn’t prove anything.’

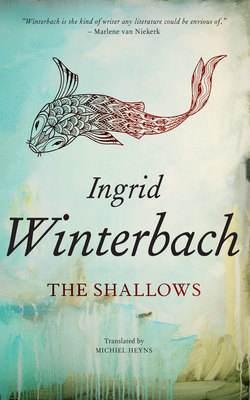

‘Look,’ said Marthinus, ‘do you remember the part in The Shallows,’ and he moved closer confidentially, ‘where a group of escaped psychiatric patients roam around running amok? Exactly that – escaped psychiatric patients! Can it be coincidence?! They’re a kind of marauding band wreaking destruction as far as they go. Their headquarters are in a room behind a mortuary. The leader spends the nights lying behind a green plastic curtain separating his bed from the stockpiled coffins, and he schemes. He schemes till the cows come home. Brilliant! Internal monologue upon internal monologue! Brilliant! A portrait of a paranoid schizophrenic Dostoevsky would have been proud of! I’ve always thought that was one of the most astonishing parts of the novel.’

(Nick remembered the scene vaguely. He’d never read The Shallows all the way to the end, he’d been too pissed off with Victor at the time.)

‘Doesn’t the man shoot the others and then himself?’ he asked. (He was impatient, he didn’t really want to be having this conversation. Kept his ears pricked up for any sound in the passage.)

‘Yes. Oh Lord. A scene that sort of reminded me of Salammbô by Gustave Flaubert. Static. Almost slow motion. But magisterial. Horrendously barbaric, the violence of it.’

‘Victor never shied away from the depiction of violence,’ said Nick drily.

‘No! He didn’t! Violence is his medium. It’s his natural language!’

‘You’d never say it, to look at him,’ said Nick. ‘However. I don’t suppose it’s a coincidence that he looks like Willem Dafoe in some villainous role.’

‘Too true,’ said Marthinus. ‘David Lynch and Tarantino are also right up his alley.’

‘Blinky couldn’t stand him.’

‘Not?! Well, I never.’

‘He thought he was a poseur.’

‘A poseur, eh? Yes, he did have rather a penchant for the affected flourish. And do you know who his heroes were?’

‘No,’ said Nick.

‘Brigadier Theunis “Red Russian” Swanepoel, and the Dalai Lama.’ He lit another cigarette. His tea must have been ice cold by now, but he drank it with undiminished relish.

‘Be that as it may,’ said Marthinus, ‘I’m prepared to bet my bottom dollar that Victor is behind both the escape and the assassination attempt. It’s there, it’s all in his novels!’

‘So?!’ Nick exclaimed. ‘Surely his novels can’t form a basis for such an assumption!’ He was impatient. He was no longer in a mood for Marthinus’ far-fetched suspicions. It was ten o’clock already. Charelle never slept this late. Should he go and tell her it’s okay, she can come to the kitchen at any time, she must be wanting a cup of tea by now?

‘Wait and see,’ said Marthinus. ‘It’s one hundred per cent Victor’s kind of scenario.’

‘From where did the patients escape?’ asked Nick.

‘Some high-security psychiatric hospital in the Moorreesburg vicinity. Only the most extreme cases are to be found there. The really severely disturbed cases. Oh Lord, it’s right up Victor’s alley. The more deviant, the better.’

Marthinus drank the last of his tea. Smoked another cigarette. Then (fortunately) he had to go and do something at home, attend to the pigs or whatever.

What should he do? Nick wondered. To go and knock at Charelle’s door now might be taking it a bit far. She might emerge of her own accord as soon as she no longer heard voices in the kitchen.

At eleven o’clock he knocked at her door gently. No response. He called her name and knocked louder. No response. Against his better judgement he opened the door gingerly. She wasn’t there. Her bathroom door was open. Nobody there. Her toothbrush was still there. Her room was tidy, as always, the bed made. Her weekend bag was on top of the wardrobe. He hadn’t heard her come in the previous night nor leave in the morning. Why should he be upset – she didn’t owe him an explanation of her comings and goings.

He had an appointment in Woodstock to view a prospective different studio space. He’d shortly have to vacate the studio that he rented in Observatory. He’d put it off for too long. He hadn’t wanted to face the disruption. He had no all-consuming desire to go and have a look this morning. But good studio space was hard to come by.

Reluctantly he went to inspect the place. (Where could Charelle have gone to so suddenly? She seldom went out.) The space looked fair enough. He’d take it. Today it didn’t matter that much to him where he worked. The work he was embarked upon was not yet substantial enough for his exhibition the following year. He’d have to work faster, produce faster. The move to Cape Town had been disruptive, had made him lose momentum. The pressure on any artist to remain on the radar was great. (He was substituting temporarily for somebody at the art school because the move had left him in financial difficulties.) In the meantime the art world was moving on. There were hundreds of young artists every day doing interesting and innovative stuff. All of them were driven and ambitious. Like Charelle. Perhaps not all of them as talented as she, but talent was no prerequisite nowadays. He would not be able to bank for very much longer on his name and his prior success.

He read the newspaper while having coffee in a small coffee shop. He saw no report on either the assassination attempt or the fugitive psychiatric patients. Could the whole thing have been a figment of Marthinus’ lively imagination? He had at times suspected the chap went overboard with things (very much like his unrealistic cousin) – as with the talk about Chris Kestell.

Late in the afternoon he arrived home. Once again there was no response at Charelle’s door.

By Saturday evening she’d still not returned. Eventually it turned nine o’clock, ten o’clock. She hadn’t said she was going away for the weekend. She usually did so. Not of course that she had to do it. She’d gone away the previous weekend with the woman in the turban. Desirée, not a particularly friendly woman. He didn’t want to phone Charelle. She’d think he was checking on her. Unforgivable. At eleven he went to bed. At first he dozed off lightly, listening for her footsteps. Somewhere in the early hours he half woke up, imagining he could hear voices on the pavement in front of the house, hoped, half-asleep, that it was Charelle, but didn’t hear her come in, and slept on restlessly.

He woke up the next morning in a grumpy mood. He should have known he would scare her off sooner or later. A middle-aged white man suddenly starting to cook for her. Her landlord to boot. Much too close for comfort. He felt embarrassed and humiliated. What had he been thinking? Then he reconsidered: apart from their eating together regularly over the last few weeks, he’d done nothing that could in any way have given her the idea that he was in the least making up to her or intent upon a mission of seduction.

By Sunday evening she had still not returned.