Читать книгу The Shallows - Ingrid Winterbach - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Ten

ОглавлениеAt four o’clock in the afternoon I report to the retirement village. (A luxury resort, it must cost a tidy sum to live here.) The iron gates swing open, I am admitted. The resort is on the edge of town, the surroundings are beautiful. The housekeeper-cum-secretary receives me. If, like most people, she is slightly wrong-footed by my appearance, she hides it well. I do, though, note that her gaze (like most people’s) lingers a fraction too long on my unsightly lip scar. She introduces herself as Miss De Jongh. So no first names. By no means a uniform and sensible shoes – a full-blown décolletage, with imposing breasts. Little low-necked black top, tight black jeans. (Would that meet with the professor’s approval – wouldn’t he prefer her in a demure uniform?) And a raving bottle blonde. Did you ever. If she’s a mite taken aback, so am I.

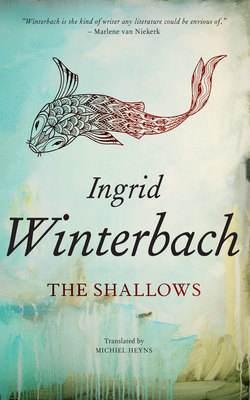

She conducts me to the stoep overlooking a lush fynbos garden. Professor Emeritus Olivier is seated in a wheelchair, with a rug over his knees. His back is turned to us. When he greets me, he shows no sign of recognition. And why would he, it was almost thirty years ago. His cranium is bonier than ever, without the softening effect of hair, of which he never had an abundance. I don’t want to stare too much and too unguardedly. He indicates with a broad, yellow-pale hand (affliction of the liver?) he wants to be wheeled down to the garden. It’s a fine day, bright, not too hot. The woman rearranges the rug. She pushes the wheelchair, I walk behind them. No chance now of any conversation. Down the winding pathway, through beds of fynbos and fragrant shrubs, up to a large pond. He indicates that he wants to stop here. We are standing on the paved edge of the pond, actually more of a dam. Big koi immediately come swimming up. One in particular remains floating near the edge, fairly close to the surface. Standing there, gazing at the fish, the professor and Miss De Jongh and I. What a bizarre apparition, seen at close quarters. Bright red, with two protrusions on either side of the mouth and something, I notice, like a blue membrane over the eyes. Could the fish be blind? The mouth, as it opens and shuts, has something obscenely sexual about it. Is it a coded message from the old father? An oblique reference to our sexual escapade almost thirty years ago?

‘Did the twins ever keep fish?’ I ask (to start somewhere).

‘No,’ says the old father (without turning his head in my direction), ‘no fish. Dogs, yes.’

‘What did they like playing with as children?’

Olivier waits a while before replying. He’s obviously not going to make it easy for me. Miss De Jongh kicks the brake firmly into place, sits down on a bench a short distance away, thrusts out her legs in front of her and lights a cigarette. Very cool and casual, and old father does not object.

‘Just what healthy, normal boys usually occupy themselves with,’ he says.

‘And that is?’ I ask.

‘They read, cycled around, climbed trees, played ball,’ he says (irritated?), ‘took part in sport. In fact, they were very gifted in that direction.’

‘Did they like reading comic strips?’

‘Within limits,’ he says. (These limits, I suspect, were of his paternal edict.)

‘I assume they were fond of drawing?’

‘Naturally.’

(Should I lean forward, my mouth to his ear, and whisper: I know what you’re capable of. I haven’t forgotten. Quickly and nonchalantly, before the blonde notices a thing?)

‘What did they draw?’ I ask.

He makes an impatient gesture. ‘Anything. Animals. Aeroplanes. What do you call them – superheroes.’

‘As children, did they attend puppet shows?’

‘I took them once or twice.’

‘Do you have any idea where their fascination with puppetry came from?’ I ask.

‘That you’ll have to ask them,’ he says.

‘And do you still have regular contact with them?’ I ask.

The man hesitates a moment before saying: ‘They are busy. They have a high international profile. But they faithfully send me catalogues of each of their exhibitions.’

Then he extends his hand wordlessly in Miss De Jongh’s direction, who gets to her feet, produces a small plastic dish from somewhere in his wheelchair and hands it to him. Now he starts feeding the koi. The obscene mouth of the fish appears above the surface at rapid intervals, gobbling at the food. I stand watching in fascination and revulsion. The interview hasn’t exactly got off to a flying start. The old father could hardly have been less cooperative. I ask another question or two, but they’re not really to my purpose. Before long he makes another hand gesture in the woman’s direction. She steps on her cigarette end, gets up, kick-releases the brake, and I get the impression the interview is over. Not once did the old man look at me. Or give any sign of recognition.

*

I carry on working at the monograph. When I try to make another appointment, Miss De Jongh alleges that Professor Olivier is in bed with a severe flu. I don’t believe a word of it, but I don’t give up that easily. I still have quite a few questions I want to ask him. Why should I let him off the hook so easily?