Читать книгу The Shallows - Ingrid Winterbach - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Two

ОглавлениеThe girl came to call him one morning.

There’s a pig in the garden, she said.

Side by side they stood on the stoep contemplating the creature. A big, black pig serenely grazing. Just as well he hadn’t started gardening yet.

Where did she think it came from? Where would it have found its way into the yard?

She didn’t know. (Although for some reason he thought she did know, but didn’t want to tell.)

Didn’t she want to take a photo, for her portfolio?

No. She didn’t photograph pigs. Pigs were bad luck.

Says who?

The people where she came from.

What kind of bad luck?

That she couldn’t tell. Any kind.

Like what? he persisted.

She didn’t want to say. It was bad luck to talk about bad luck, she said.

She believed that?

She wasn’t going to take any chances.

This morning he found her pretty, this girl with the abundant hair and the soft, tea-coloured skin.

They say pigs are very intelligent, he said.

So is the devil, she said.

Oh yes, he said, and did she believe in the devil?

She said nothing, just smiled slightly. (He suspected she was pulling his leg.)

Later the pig lay down in the shade of a shrub. Perhaps a suitable subject for a painting, but he was no painter of pigs, or people. The new house still had a chaotic feel to it. The sitting room was filled with unemptied boxes. He remained conscious of the pig in the garden, in the shade. He hadn’t yet tried to find the place next to the fence where it might have got in.

In the late morning someone appeared at the gate. A man. He’d come to collect his pig, he saw it lying in the garden. The man had a big, open, attractive face. Amiable. Trusting. Tanned.

He didn’t know one was allowed to keep pigs in a residential area, said Nick.

He had a big plot, up there, against the mountainside, he gestured with his shoulder.

‘Marthinus Scheepers,’ he said, extending his hand.

‘Nick Steyn.’

The man’s grip was firm. Probably needed to be, to keep pigs in check.

‘Come by sometime,’ said Marthinus, ‘come meet the other pigs.’ (He uttered a short, cheerful chuckle.)

There was something about the man. The big, harmoniously sculpted head and features. A noble face. Had something gone wrong, was he feeding with the pigs now?

‘Does the pig have a name?’ Nick asked.

‘President Burgers,’ Marthinus said. ‘Primus inter porcos. A true leader. A pig of destiny.’

‘I see,’ said Nick.

Man and pig departed. Almost near-neighbours. He’d have to go and see. Something about the man, something about the pig. Both with something distinguished about them? Both of them noble of countenance and harmonious of proportion.

*

Nick had recently bought this house in Tamboerskloof. He didn’t work there, was renting a studio in Observatory for the time being. Well out of Stellenbosch, that hotbed of complacency; a fresh start, after the breakdown of the relationship with Isabel. He’d hardly moved in, when a girl knocked at his front door one morning. She’d heard that he had rooms to rent. Where had she heard that? From the woman at the gallery. He’d hardly even breathed the possibility of rental, and already there was a potential lodger on his doorstep. The girl was wearing black velvet trousers, scuffed boots, a baby-blue fleece top that looked like a pyjama top. Her hair curled and twirled wildly around her head as if she’d just hitchhiked here on dusty roads. Her eyes were alert. Her name was Charelle Koopman. She didn’t look much older than twenty. She was doing a photography course at the Peninsula Academy of Art. This was her first year. She took her studies seriously. Where was she from? he asked. From the West Coast, Veldenburg. But she’d been in Cape Town since the previous year. The next day she moved into the spacious back room.

And now, suddenly, one day, there was a man with a pig in his front garden. His father and a nephew of his had bought a few pigs between them way back: Large Whites, if memory served. His father was working in Johannesburg and had the pigs looked after on his sister’s farm in the Roossenekal district. Something befell the pigs. He couldn’t remember what. The pigs were big and beautiful and his father had animatedly demonstrated how high they stood and how they gleamed with fat, and then something happened. Was there anybody left alive who would know what had happened? There had to be someone who knew what had befallen the pigs.

Nick’s sister and his eldest brother wouldn’t know, because they were, as far as he was concerned, write-offs. His sister a heart surgeon sweeping through the wards of some academic hospital, teams of white-clad underlings bearing beating hearts on ice in sterile containers hot on her heels. She wouldn’t have time for pig memories. His eldest brother was a tycoon. Well, good for him. The past was not part of his frame of reference either. The only one who would have known – his other brother, five years older than he – wrote himself off big time on a motor bike in Namibia. Smuggling diamonds. (Who was to know?) His hero and tormentor. Nick was the youngest. Sickly child, everybody thought he was retarded. He led a secret life, his fantasies riding roughshod over him. Horrendous nightmares, visions of hell at a tender age; dreamt Bosch before he saw his work. Slid around on his belly in the garden like a snake or a snail, looking for something he couldn’t find at eye level. What the hell, he’d eat worms if need be. His sister did have a soft spot for him; eldest brother blinkered like a horse headlong on his way to tycoon-dom. That left Nick with smuggler brother, his hero. Smoking buddies, drinking buddies, porno-mag buddies and he barely older than ten, twelve. Brother wiped his arse on the world and was irresistibly charming on top of it. He made Nick draw. All positions. Brother was the first person who recognised Nick’s ability. Nick was a slow developer, and it was only when everybody else stopped growing that he shot up. Asthma, ringworm and pox could no longer hold him back. First he wanted to become a rugby player, then a bomber pilot. Become an artist, said his brother. Painters are sissies, said Nick. Brother showed him a photo of Jackson Pollock energetically at it. Does that look like sissy-work to you? (In the brother’s eyes it also counted in Pollock’s favour that at forty-four, drunk, he had written himself off spectacularly in a car.)

Nick found dark women most attractive, but when it came to getting down and dirty he’d always preferred blondes. Strong calves, legs slightly bandy. Gap between the front teeth. Expression somewhere between brain-dead and horny. For god’s sake just not wholesome blondes. Slightly off, slightly slutty and clapped-out. The vacuous, dreamy gaze at parties after twelve. As far as sex was concerned? By his mid-thirties he’d had enough of it to last him two lifetimes. Up to and including his short-lived marriage. And after that, after his failed marriage, his relationship with Isabel for the last seven years. Her hair as white as flax and her skin honey-coloured in summer. Heavy eyelids, a languid gaze, a tentative smile. Her back and limbs long and narrow, like those of a Cycladic funerary idol.

*

One morning when he was backing out his car on his way to work, he came across Marthinus Scheepers on his morning walk. No pig at his heels.

Marthinus was wearing a kind of Peruvian woollen cap, a snazzy tracksuit bottom, strange boots and a brightly coloured windbreaker. He greeted Nick cordially. Come by this evening, he said, come and watch a video with us.

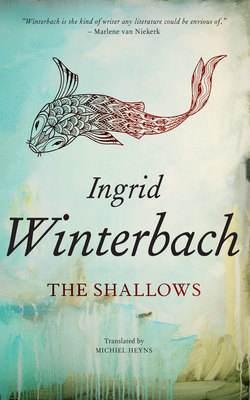

That afternoon Nick found a postcard in his postbox. It was a reproduction of El Greco’s portrait of Vincenzo Anastagi. The message on the back read: Any extra copies of The Shallows? V.S.

V.S., would you believe it?! Could only be Victor Schoeman. A South African stamp. Posted here, then. This did not bode well. Did it mean that Victor was in the country? When last had they seen each other? (And that, come to think of it, went for Blinky, and Chris Kestell, and Marlena as well?!) Did he have any desire to resume contact with Victor? No. The extra copies of The Shallows that he’d stored for years, he’d had pulped when he heard nothing more from Victor. Why should he get stuck with the debt and the boxes of books?

Good choice of postcard, Victor, he thought. The El Greco was one of his favourite paintings. He’d last seen this painting in the Frick with Isabel, on their final, fatal trip together, shortly before the end of their relationship, in November the previous year. Not that he’d been all that keen to visit the Frick (had by and large had his fill of Western painting), but for her it had been a trip fraught with meaning, a kind of pilgrimage perhaps. And there in the Frick she’d suddenly pressed her hands to her ears (why not her eyes, he’d wondered), gone in great haste to claim her coat from the cloakroom, and run away (he couldn’t describe it in any other way). He’d followed, into the cold streets, a freezing wind (as if from Siberia) on their cheeks and wet snow in the streets. He managed to lure her into an Oriental museum and teahouse, where he could calm her down with a delicate snow pea and shrimp soup and tea from little Japanese earthenware teapots. Some colour returned to her cheeks. (I can’t any longer, he thought, I can’t carry you any longer, it takes too much out of me.) She cheered up so much that later she was even exuberant, flirtatious, but the day had been spoiled for him. He was morose; he no longer wanted to be charmed by her. Forgive me, she said, I don’t know what’s wrong with me.