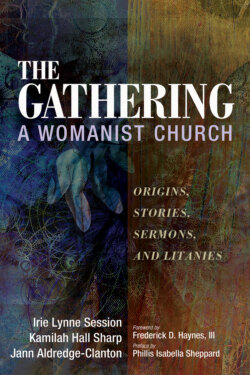

Читать книгу The Gathering, A Womanist Church - Irie Lynne Session - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Creating a Womanist Church

ОглавлениеBefore Rev. Kamilah Hall Sharp moved to Dallas to pursue a PhD in Hebrew Bible at Brite Divinity School, her Memphis pastor, Rev. Virzola Law, introduced her to Rev. Dr. Irie Lynne Session. Kamilah and Irie became good friends, sharing their passion for social justice and their call to preach.

Need for a Womanist Church

When Kamilah began visiting churches in Dallas, trying to find a good fit for her family, she noticed numerous churches that did not allow women preachers. Whenever someone told her of a new church to visit, she went to their website and looked at their leadership. Often she found all males in pastoral positions and when there was a woman included, she was over religious education or human resources. She could not attend a church where she would not be able to live into the call to preach that God had placed on her life. Also, she did not want her daughter to be in a church that would place limits on how God could work in her life because she is a girl. In the numerous churches Kamilah and her family visited, they very seldom heard any sermons that included social justice issues and that lifted women in the biblical text or in current times. Social justice, including justice and equity for women, was important to them, so they could not join any of these churches.

While they were still in the process of visiting churches, Kamilah’s husband, Nakia, said to Irie, “You should go be Moses.” He suggested she go plant a new church. Irie was not interested in planting a church and responded, “No, and if I were to ever do anything, we would have to do it together.” Kamilah was just beginning her PhD coursework and caring for her daughter who was in kindergarten and transitioning to a new school, so she was not interested in planting a church either. At that time Kamilah had no desire to be a pastor.

More than a year later, Irie had an idea for a Womanist Seven Last Words service on Good Friday.24 The service would include seven womanist preachers from various denominations, preaching the seven last sayings of Jesus from the cross, seven minutes each. This unprecedented and forward-thinking vision resulted in seven women gathered on Good Friday in Dallas, Texas, to reimagine, through womanist interpretation, Jesus’s seven last sayings from the cross. Each of the seven women brought messages of hope, freedom, and healing, not just for the guests, but for themselves. It was a rarity, even in 2017, for seven Black preaching women to be in one place, at one podium, on one preaching assignment.

To their surprise, the service was very well attended, with a diverse crowd, and well received. Those in attendance embraced this style of liberating preaching and inquired when and where they would be able to experience this again. People asked, “Where can I hear more of this preaching?” Irie and Kamilah responded, “You really can’t hear womanist preaching Sunday morning in Dallas.” After having this question raised several times over a few months when they preached in other places, they began to ask the question: “What would it look like to have a space where people could come and regularly experience womanist preaching?”

Beginning a Womanist Church

At this time, Rev. Yvette Blair-Lavallais, one of the preachers in the Seven Last Words service, was leaving her position at a United Methodist church. Kamilah and Irie, recognizing there is strength in numbers, invited Yvette to join them at Starbucks to begin a conversation about creating a space for womanist preaching. The idea of having three women working together to carry the load was intriguing. In this first conversation, they discussed what a space for womanist preaching might look like if they worked together. They asked questions: “Who do we envision in the space? What would the space look like? What would be important to us?” After their first meeting they took time to pray and give thought to each of these questions.

When they came back together, they decided that they wanted to create space for womanist preaching in Dallas. In this conversation, they all lifted three concerns as important: womanist preaching, social justice focus, and affirming LGBTQIA people. They agreed that a space for womanist preaching would be healing, authentic, and necessary. The space would be healing because they knew people who had been hurt by life and the church. The space would be authentic because they knew they would show up authentically and make room for others to be their authentic selves as well. In this space, people would not have to pretend to be someone other than who they were. The space would be welcoming to all people. They knew that no space like this was available to them. The space was necessary because there were many people who were being wounded by harmful interpretations of biblical texts, hurt by church, and disenchanted with Christianity.

They also agreed on three missional priorities: (1) racial equity, (2) LGBTQIA inclusion, and (3) the dismantling of patriarchy, misogyny, and sexism (PMS). Equally important, the space could not have a hierarchical framework. For this reason, each of them would have equal input and an equal vote on everything, and they would call themselves “co-leaders.” The space would not be a “church,” but a place where people could gather and worship. While this may sound like a church, they were not setting out to start a church, so there was no need for them to be referred to as “pastors.”

In order to properly prepare, they agreed to take some time to find a location and make sure all the components were in place to ensure success in creating this new space. Irie and Kamilah are both ordained in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), so Irie sent an email to the Disciples of Christ Area Minister, asking him to send a message to local churches to see if anyone would agree to offer them permanent nesting space. They were creating this space with no support from any denomination and few personal resources; hence, they did not want to incur a large overhead expense that would take away from their ability to minister effectively. There were five responses from different churches on the day the email was sent. Kamilah, Irie, and Yvette lived south of Dallas, and the churches that initially offered them space were farther north. A few days later, Rev. Ken Crawford, the new pastor of Central Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), also responded, offering them space. Irie was a member of this church, Kamilah had attended several times, and they both had preached at Central. This was the location they were hoping to get because it was more centrally located and a wonderful facility.

Now with a secure location they began to plan an inaugural service. Yvette, Irie, and Kamilah decided to have a one-hour service on Saturday. For them it made sense to have a Saturday service because there were many people who were interested in participating who worked in various churches on Sunday. Also, there are thousands of churches in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, but few offer services on Saturday. They then considered what the service would look like, and they agreed to have “Greet & Tweet,” weekly Communion, rotating and tag-team womanist preaching, and a question and discussion time called “Talk Back to the Text.”

For weeks they advertised on social media outlets. On Friday evening before the inaugural service, they set up Central Christian Church’s fellowship hall. Since they knew they were creating space for people who were hurt by church, they thought people would feel more comfortable in the fellowship hall than the sanctuary. The chairs were set up in a half circle with an aisle and the podium was on the floor with the chairs, instead of up on the stage, to prevent a hierarchical visual.

On October 16, 2017, the day of the service, they arrived and began to wait, not knowing if anyone would come. Cars started pulling up on the parking lot, and people began to come into the fellowship hall. Approximately eighty-five women, men, and children of different races attended that first service. Rev. Kamilah, Rev. Irie, and Rev. Yvette tag-team preached, and the service was complete in one hour. It was well received, so they agreed to keep going. The following week they prepared and showed up, wondering if people would come again or if it had been a one-time event. Once again people showed up. It became an ongoing joke among the co-leaders, “Is this the week no one will show up?” Nevertheless, week after week people kept coming and have continued to come every week since they started.

Central Christian Church is a community church that opens its doors to a variety of groups, organizations, and more. Central had booked the fellowship hall for a group’s Christmas fundraiser before Irie, Kamilah, and Yvette began holding services there. This meant that in order to have a worship service one week in December of 2017, they would need to move into the sanctuary. Kamilah was concerned about people she thought did not want to be in a church. Reluctantly, they moved the service to the sanctuary and put a podium on the floor so they could be with the people. To their surprise, people loved the sanctuary. A teenage boy who had been attending regularly asked Irie if services could be there from then on. Several others also commented about how they liked being in the sanctuary better. At that time, they realized “The Gathering” was becoming a church. Shortly thereafter, Irie suggested adding “A Womanist Church” to the name; they became “The Gathering, A Womanist Church,” and the three of them became co-pastors.

Challenges and Rewards of Creating a Womanist Church

Active on social media, each of The Gathering’s co-pastors knew they had to use social media to promote and reach more people. Irie used “Facebook Live” often in her own work, and they agreed to use it for The Gathering. They were concerned that if they streamed the entire service, people in Dallas would not come because they could watch online. The original compromise was to stream only part of the service. After a few weeks, they realized that many more people were watching from outside the Dallas-Fort Worth area and wanted to experience more of the service. So they began streaming the service until the sermon was completed and ended before Talk Back to the Text. At this point they thought the conversations during Talk Back to the Text were intimate, and they did not want to share them online. They began to have more ministry partners online who were consistently watching and indicating they would like to participate in the Talk Back to the Text portion of the worship. During this time they were also noticing that the number of online viewers was steadily increasing to hundreds every week. It became clear that they needed to engage this online community and to keep connected to them as well, so they decided to stream the entire service.

Everything that occurred up to this point happened with only the personal resources of the co-pastors and the support of those who were partnering with them at The Gathering. They agreed not to have members, but ministry partners. Ministry partners are those who attend regularly, either in person or online, support the ministry financially, and use their gifts in the community. Not having enough financial support limited their ability to do some things that they wanted to do. Finances continue to be a challenge to this day.

However, the rewards of creating a womanist church are many. It is rewarding to hear people talk about what The Gathering means to them. People who have not attended church in over twenty years come faithfully to The Gathering. When the co-pastors travel around the country, they meet people who say they feel inspired as they watch The Gathering online week after week. It is a great feeling for the co-pastors to know their ministry is making an impact. Another reward comes from making space for other womanist preachers to be heard. When The Gathering began, the co-pastors stated they would open the pulpit at least once a quarter to allow other womanist preachers a space to preach. The reality is there are many great womanist preachers who do not have the opportunity to preach often because there are not many pastors who afford them an opportunity. These are voices people desperately need to hear. For the co-pastors, knowing God has used them to create space for other womanist preachers to be heard is beyond wonderful. Each woman who preaches at The Gathering is paid an honorarium because the co-pastors know all too well how women are not paid equally to men, or sometimes at all, to preach. In creating The Gathering they wanted to make sure they not only preach about justice, but act in just ways.

Toward a Womanist Ecclesiology

The co-pastors of The Gathering, a new model of ministry and church plant, were committed to taking their “spiritual lives into their own hands, refusing to seek permission”25 to create a womanist ecclesial community that resists white supremacist capitalist patriarchy. They sought to implement a womanist ecclesiology as a strategy of resistance to oppression in both church and society. A womanist ecclesiology as resistance is a direct result of Black clergywomen’s experiences in the North American Church with the quadripartite oppressive realities of racism, sexism, classism, and heterosexism. These injustices are forcing them to “forge new pathways to escape religious oppression, marginalization, and colonization while remaining connected to Spirit.”26

The North American Church has been derelict in its Jesus-identified mission of liberating the oppressed. Even so, Black clergywomen, including scholars and theologians, are forming ecclesial communities outside institutional and denominational structures to find healing, wholeness, social justice activism, and the freedom to use and maximize their God-given gifts to transform church and society. Research bears out that, “for a large number of women, the patriarchal and institutional church is no longer a meaningful framework. They begin to create new forms of being church often in small informal gatherings of women (sometimes men) who celebrate liturgies, read Scripture and work for social justice.”27

When Rev. Irie, Rev. Kamilah, and Rev. Yvette started dreaming and visioning of The Gathering, they didn’t have in mind a church. In fact, because of the baggage they carried from previous experiences with church (abuse, sexual assault, and racial trauma), they chose not to call their gathering a “church.” At first, they were simply “The Gathering.” However, people who began to journey with them helped shape and name the community “church.” Rev. Dr. Irie, one of the co-pastors of this new model of church, initially led by a partnership of three Black seminary-trained clergywomen, realized she was in a perfect position to study womanist ecclesiology. She wanted to understand more in order for their ecclesial community not only to survive, but also to thrive.

Eager to learn more about creating a vibrant, thriving womanist ecclesial community that would have longevity, Irie applied for a Pastoral Study Project grant from the Louisville Institute.28 In 2019 she received a $15,000 grant to work on a research project titled “Womanist Ecclesiologies: Black Clergywomen Resisting White Supremacist Capitalist Patriarchy.” Then she embarked on a journey of discovery—a fact-finding mission. She set out to explore and find answers to questions that have arisen out of her ministry with The Gathering, A Womanist Church: (1) What is a womanist ecclesiology? (2) How can a womanist ecclesiology empower Black clergywomen to partner in shaping communities that resist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy and liberate the oppressed? (3) What denominational and/or funding support is needed for womanist ecclesial communities to thrive? She studied five Black clergywomen-led ministries: Middle Collegiate Church in New York City; Lewa Farabale, A Womanist Gathering in St. Louis, Missouri; Pink Robe Chronicles, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina; City of Refuge in Los Angeles, California, and Rize Community Church in Atlanta, Georgia.

To gain clarity for her research, Irie developed working definitions for key terms: “ecclesiology,” “womanist ecclesiology,” and “white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.”

She defines “ecclesiology” as “the theological interpretation of what it means to be church,” highlighting the work of Natalie K. Watson in Introducing Feminist Ecclesiology. Because the theological meaning of church has been subject to patriarchal interpretations, Watson argues for an ecclesiology over against a discussion of women in the church or women and the church. She maintains, women are church.29

Until she began her research, Irie had never read a book or article that referenced “womanist ecclesiology.” She discovered a YouTube video featuring Bishop Yvette Flunder, preaching a sermon titled “A Womanist Ecclesiology.”30 While Bishop Flunder doesn’t provide a formal definition of a womanist ecclesiology, she does describe its manifestation. Flunder envisions a womanist ecclesiology in response to what she calls, “unbridled patriarchy.”31 She explains: “There needs to be an ecclesiology or a way in which we see God and ecclesia—the community of the faithful, from a womanist perspective. That means, home and heart are important; it means all our children matter; it means health is everyone’s right; it means there is no group of people upon whom everyone else can step up from at that group of people’s expense.”32 Mining Bishop Flunder’s sermon “A Womanist Ecclesiology” for wisdom, Irie defines a womanist ecclesiology as “ways of thinking theologically about doing and being church that take into account the norms, practices, ethics, wisdom, survival strategies, and lived experiences of Black women which lead to the liberation and thriving of all people.”

The work of bell hooks informs the definition and application of the phrase “white supremacist capitalist patriarchy” to capture all the ways in which Black women experience the intersections of oppression. In “bell hooks: Cultural Criticism & Transformation,” we gain clarity for her rationale in using the phrase:

I began to use the phrase in my work “white supremacist capitalist patriarchy” because I wanted to have some language that would actually remind us continually of the interlocking systems of domination that define our reality and not to just have one thing be like, you know, gender is the important issue, race is the important issue, but for me the use of that particular jargonistic phrase was a way, a sort of short cut way of saying all of these things actually are functioning simultaneously at all times in our lives and that if I really want to understand what’s happening to me, right now at this moment in my life, as a black female of a certain age group, I won’t be able to understand it if I’m only looking through the lens of race. I won’t be able to understand it if I’m only looking through the lens of gender. I won’t be able to understand it if I’m only looking at how white people see me.33

White supremacist capitalist patriarchy speaks to the ways in which Black women, on a daily basis, experience life. All aspects of Black women’s lives, even those parts that are positive and nurturing, are negotiated with resistance through the prism of white supremacist capitalistic patriarchy—the interlocking systems of race, gender, class, and age discrimination.

In her research, Irie found no academic or scholarly resources specifically addressing a theological constructive framework for a womanist ecclesiology. While there are, in fact, numerous books and articles on Black women in the Black Church, none highlight the formation of church vis-à-vis a womanist theoretical lens.

Although there is indeed a dearth of academic material relative to a womanist ecclesiology, she discovered scores of Black clergywomen currently engaged in what Lyn Norris Hayes coins as “practical womanism”34 or what Irie refers to as “practical womanist ecclesiology.”35 She found myriad ways and platforms in and through which Black clergywomen are engaged in practical womanist ecclesiology. In other words, there are Black clergywomen living out a womanist ecclesiology in their respective congregations, digi-church ministries, Cyber Assemblies,36 and womanist gatherings even though they do not identify their community as “church,” or ekklesia. Building upon Hayes’s definition and articulation of “practical womanism,” Irie defines “practical womanist ecclesiology” as the “performance of a womanist hermeneutic in the everyday lived experiences of Black women in order to resist oppression in its myriad manifestations and facilitate communal flourishing and wholeness.” A womanist hermeneutic is embodied and articulated in the thinking, being, and doing of Black women. Because womanists learn to work around systems of white supremacist capitalist patriarchy, a practical womanist ecclesiology of necessity is wide and broad enough not to be confined to a building that requires maintenance or a mortgage. As God’s Spirit “blows wherever it wishes” (John 3:8 CEB), so are the creative contours of a practical womanist ecclesiology.

Irie’s research project revealed in very practical ways that, like God’s Spirit, the articulation and implementation of a practical womanist ecclesiology cannot be contained, confined, or controlled by denominational, judicatory, or economic systems, or by institutional structures or ideological frameworks that undermine its premise. Her interviews with womanist clergywomen clarified this reality. For example, the co-conveners of Lewa Farabale: A Womanist Gathering in St. Louis realized they had “to do something different.” Rev. Lorren Buck, one of the founders of Lewa, remembered sharing with her colleagues: “We can’t continue to repeat what has been placed before us and think that is going to be sufficient in liberating women, specifically, not Black women. Because the church is full of Black women who don’t have the equal voice and say of their male leadership that believes that their role is really to support the vision of a man with their labor and with their money . . . everything. And that Black women should gladly do it without question.” The three Black clergywomen who founded Lewa had an epiphany born of the Spirit: “What if there was a church that had three pastors, one that resisted hierarchical arrangements?” They had no location, limited financial resources, and no denominational support. What they did possess was a prophetic knowing, that is, an organic way of knowing the deepest needs of a certain segment of society and strategies to meet those needs. In her book Toward a Womanist Ethic of Incarnation: Black Bodies, the Black Church, and the Council of Chalcedon, womanist ethicist Eboni Marshall Turman describes this prophetic knowing as a womanist epistemology. A womanist epistemology emerges from a posture of radical subjectivity that “resists notions of black women as passive subjects and rather determines that their distinctive consciousness empowers them to proactively engage and shape their own vindication.” Turman argues that Black women are not “broken subjects.” On the contrary, “radical subjectivity allows for a revaluation of the white racist, patriarchal, capitalist system of values that subjugate black women by privileging black women’s embodied experiences rather than oppressive ideologies, theologies, and practices.”37

A Constructive Framework

From onsite interviews and participant observations, Irie discovered a constructive framework for a womanist ecclesiology, consisting of at least six components. A womanist ecclesiology is artistically expressive, social justice-oriented, informed by a communal Christology, organically trauma-informed, maintains God is Universal, and situates womanist preachers as primary proclaimers.

1.Artistically Expressive

The ministries of the clergywomen Irie observed are artistically expressive. Each displayed creativity of color, vibrant visual imagery in clothing and symbols, stirring music, and creative use of digital spaces and social media apps. For example, as we were in the process of writing this book, the world was hit with a pandemic, COVID-19, the likes of which we had never seen before. Among other adjustments required to ensure the safety and well-being of each person, religious leaders were forced to reimagine processes for carrying out worship and other religious gatherings. What became clear was that there was a group of people, Black clergywomen, already navigating efficiently and creatively alternative modes of communicating spiritual and religious services and conversations. In an article titled “While More Black Churches Come Online Due to Coronavirus, Black Women Faith Leaders Have Always Been Here,” Candice Benbow, theologian, essayist, and creative, describes the prophetic innovation of Black clergywomen as a response to white supremacist capitalist patriarchy and heteronormativity: “While some congregations have always had a digital presence, there is one group that has been most consistent with providing ministry in the digital realm. Using social media apps, streaming platforms and websites, Black women have created their own spaces to do the work of faith and spirituality.”38

Black clergywomen, such as Rev. Dr. Melva Sampson, curator of Pink Robe Chronicles, and Ree Belle and Rev. Lorren Buck of Lewa Farabale, as a strategy of resistance, had already carved out digital spaces for themselves to preach, teach, write, and facilitate social justice organizing in order to “do the work their souls must have.”39 These resistance strategies included art, rituals, and curating spiritually expansive space—grounded in sound theological reflection. As a means of survival and subsequent thriving, Black clergywomen were ahead of the curve in taking ministry online by crafting their own digital resumes. The North American Church can benefit from Black women as connoisseurs of creativity by consulting and contracting with them to develop relevant digital ministry that is also artistically expressive, thus speaking to the soul.

2.Social Justice Orientation

Irie’s exploration of the ministries of six clergywomen made apparent the social justice orientation of a womanist ecclesiology. Each clergywoman is engaged in ministry in the street. “Ministry in the street” as described by Rev. Dr. Maisha Handy, senior pastor of Rize Community Church in Atlanta, is “resistance to empire.” Bishop Yvette Flunder, senior pastor of City of Refuge in Los Angeles, describes their social justice ministry this way: “It means all our children matter; it means health is everyone’s right; it means there is no group of people upon whom everyone else can step up from at that group of people’s expense.” Because Bishop Flunder sees “a connection between hatred and abhorrence of LGBTQ persons and an idea that cheapens the value of women and girls,” City of Refuge has a robust LGBTQIA+ ministry. Rev. Dr. Jacqui Lewis, senior pastor of Middle Collegiate Church in New York City, explains that their first social justice issue was feeding folks with HIV/Aids, which then led to addressing economic injustice, then a living wage and paid time off. Dr. Jacqui and Middle Church operate with a global understanding that we’re all connected. She says, “If someone else is hungry, our stomachs are growling.” Racial justice became a key issue for Middle Church when Treyvon Martin was killed. That justice work put her squarely in the Black Lives Matter Movement. Middle Church, like each ministry studied, is anti-racist and pro-LGBTQ, where all voices matter.

3.Communal Christology

A womanist ecclesiology is informed by a communal Christology. Jesus invited a community of men and women to follow him, learn from him, love one another, and then communicate that transformational love in the world. Dr. Melva Sampson and Pink Robe Chronicles (PRC) demonstrate this communal element each Sunday morning in their Cyber Assembly on Facebook Live. For Dr. Sampson, the PRC community preaches with her. For example, if she references a website or quote during her sermon but can’t remember where it’s located, someone from the PRC community finds it and posts it in the thread. Dr. Sampson, a homiletics professor and practical theologian, describes her sermon offering as an “active communal approach” to preaching and explains: “We all preach it together because they (PRC community) have an active role in it. It’s not, ‘This is what I came to give you’—it may start out that way, but the PRC community is like seasoning on food; they enhance whatever dish is being made by me.”

4.Organically Trauma-Informed

“Trauma is an emotional wound resulting from a shocking event or multiple and repeated life-threatening experiences that may cause lasting negative effects on a person, disrupting the path of healthy physical, emotional, spiritual, and intellectual development.”40 At Rize Community Church, there are women who have been prostituted as well as members with histories of drug addiction. Dr. Handy and other ministry leaders understand the trauma that accompanies such histories and have created an environment where each person feels valued and is able to live authentically. Rize also has a large Black LGBTQIA young adult population, many of whom have been dislocated and disconnected from their families due to unhealthy theological and biblical perspectives.

There is also cultural trauma which occurs when “members of a collectivity feel they have been subjected to a horrendous event that leaves indelible marks upon their group consciousness, marking their memories forever and changing their future identity in fundamental and irrevocable ways.”41 Black women live at the intersection of varied and multiple levels of trauma, such as race-based and gender-based discrimination and oppression. By virtue of Black women’s lived experiences at the intersection of racial and gender-based trauma, a womanist ecclesiology speaks to the impact of that trauma on their relationships with other people and their understanding of God and spirituality. A womanist ecclesiology means womanist practitioners understand how vulnerable people are who have been traumatized and that their sense of safety can be triggered by any number of things. Most importantly, those who have been traumatized need to be encouraged and supported in being hopeful about their own healing and wholeness. Consequently, a trauma-informed approach to ministry asks and seeks to address the question, “What happened to you?” rather than “What did you do?” A womanist ecclesiology, as evidenced by all the ministries in Irie’s study, is a conduit of healing and wholeness for humanity.

5.Universal God

A womanist ecclesiology is wide and broad enough to encompass a variety of spiritual and religious expressions. It sets forth that God is Spirit and cannot be contained, controlled, or confined. One of the most clarifying experiences of the universality of God occurred while Irie attended Sunday afternoon worship at Rize Community Church. Rize is a blending of Christianity and Ifá, a Yoruba religion originating in West Africa. This particular Sunday, Rize celebrated Pastor Regina Belle-Battle42 with a Kwatakye award presentation. The Kwatakye is an African symbol for bravery, fearlessness, and valor. Kwatakye was a famous, fearless African warrior and captain. The manner in which the women of the congregation honored Pastor Belle-Battle was especially moving to Irie. They engaged in a naming and water ritual and presented Pastor Belle-Battle with a piece of kente cloth as a stole.

Similarly, Dr. Melva Sampson experiences God as Universal as she embraces an Afro-centered Christian spirituality. In a sermon preached at the Festival of Homiletics in Minneapolis, Minnesota, Dr. Sampson made the following assertion:

I am unapologetically Afro-centric; I see myself in the words of Dr. Molefi Asante as a subject in a world, in a Christian tradition, and in a preaching praxis that so often objectify me. Hence, I illumine the history, the current experiences, and the hopes of African diasporan people in contrast to what is often posited from particular hegemonic, colonialist, and imperialist pulpits . . . I am also unapologetically a follower of Jesus.43

Upon hearing her words, those in attendance, particularly the Black clergywomen seated with and around Irie, erupted with thunderous applause. Dr. Sampson expressed in her sermon what all of them believed and have in one way or another claimed as true for themselves and their respective ministries—it is possible to mine the values, virtues, and culture of their African heritage and be followers of the life and teachings of Jesus Christ, all at the same time, because they believe they serve a Universal God. More specifically, Black Christian women who are clergy, social justice activists, preachers, biblical scholars, and theologians are finding healing and wholeness rooted in learning their ancestral African heritage and histories.

6.Womanist Preachers as Primary Proclaimers

In each of the ministries Irie explored, the primary preachers and proclaimers are womanist practitioners. Some are senior pastors with several paid staff members, as in the case of Dr. Jacqui Lewis and Dr. Maisha Handy. The word of liberation, transformation, and hope comes forth out of the mouths and bodies of Black clergywomen.

In making her way toward this revolutionary and transformational constructive framework, Irie found it helpful to reimagine Black women in terms of their embodiment. Specifically, she considered what it means to live, work, and carry out ministry in a Black female body, particularly when “the various ways in which black bodies are put upon by structures and ideologies of oppression land upon the black female body.”44 Malcolm X, during his iconic May 1962 speech in Los Angeles, confirmed a truth about Black women’s embodiment that most Black women, even to this day, resist internalizing: “The most disrespected woman in America is the black woman. The most un-protected person in America is the black woman. The most neglected person in America is the black woman.”45 As a consequence of this flagrant discounting and dehumanization, Black female bodies are not typically embraced or sought out in North American religious, theological, and ecclesial spaces as sites of knowledge production and socio-religious innovation and transformation. However, the North American church would do well to cease misinterpreting the Black female body. In order to accomplish such a paradigmatic shift, the North American church might reimagine the body of Jesus. That is, consider alternative theoretical models of incarnation. Here’s what I mean: “Just as Jesus in-fleshed God, God is in the flesh of Black women as well.”46 Below, Marshall Turman articulates the idea of God in Black women’s flesh, as a womanist ethic of the incarnation:

Positing black women as Jesus, that is, as the image of God’s ethical identity in the world, however, a womanist ethic of incarnation insists that the black church’s parousia is possible only insofar as it remembers Jesus by looking to the bodies of black church women who, in their apparent brokenness, claim that God is not only with us in terms of God’s presence in history on the side of the oppressed; but even more, God is in us, namely, that God is in the flesh of even the “oppressed of the oppressed.”47

Funding

Irie discovered that, with the exception of Middle Collegiate Church, each ministry lacked denominational funding to support any of these Black clergywomen. They relied on offerings from the church, donations from the larger community, and various grants. Each of the Black clergywomen held a second conventional job or relied on speaking and teaching to augment their income.

In the case of The Gathering, A Womanist Church, the co-pastors received a New Church grant after being in ministry without compensation for eight months. This grant enabled them to split a very modest salary for a year and a half. At the writing of this book they have five months of grant money remaining, and do not know if the grant will renew. Whether it renews or not, The Gathering will continue listening to the Spirit and use creativity to develop strategies for economic thriving. The North American Church also has a responsibility and a challenge to provide strategies for these much-needed ministries to attain economic sustainability.

Guidance for Creating Womanist Churches

As Irie’s study clearly demonstrated, many people are discovering the power of a womanist ecclesiology. A womanist ecclesiology empowers Black clergywomen to partner in shaping communities that resist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy and liberate the oppressed. Many people in our country and around the world are looking for places like The Gathering, a community fully practicing a womanist ecclesiology. There are millions of churches in the United States alone, but The Gathering is distinct as the only church founded and identified as a womanist church. The Gathering co-pastors and ministry partners hope to inspire the creation of many more womanist churches. They offer guidance for creating a womanist church:

1.Begin by praying about creating a womanist church. Planting a new church takes a great deal of work and commitment. Do not try to plant a womanist church just because it sounds good; plant a womanist church only if called to do it. Kamilah, Irie, and Yvette felt called to create The Gathering; they could no longer wait for others to give them space. They had to create the table where they wanted to sit.

2.Create a womanist church in partnership with others. The Gathering has been a model of partnership, begun intentionally with three Black clergywomen. Each wanted other gifted women to carry the load with her and to show the world that Black women can work together. In 2019, Yvette left The Gathering to work on food justice issues and other ministries in her denomination. Irie and Kamilah continue to co-pastor, believing this is the best model. They also work with ministry partners to fulfill the mission of The Gathering. They know that Jesus did not work alone, and neither should they.

3.Create a womanist church with clearly stated womanist beliefs and priorities, and stick to them. Stand strong in these beliefs to bring the vision to reality. When the co-pastors started The Gathering by stating social justice priorities of racial equity, LGBTQIA inclusion, and elimination of patriarchy, misogyny, and sexism (PMS), they knew they would turn many people away, but they took this stand anyway.

4.Be open to a variety of creative modes of worship and to diverse spiritual and religious expressions, and be artistically expressive in liturgies. Engage womanist preachers as the primary proclaimers, informed by Black women’s experiences of trauma and resistance to oppression.

5.When creating a womanist church, define “success.” For The Gathering, success did not mean having a big crowd of people, but helping to transform people and to create an equitable world.

6.Explore many funding options and develop creative strategies for the economic thriving of a womanist church. Listen to the Spirit and have faith in God’s guidance.

7.Claim the vision of womanist churches bringing liberation and wholeness to all people. Believe that creating a womanist church will contribute to bringing this vision to reality in order to transform church and society.

24. The Seven Last Words or Seven Last Sayings of Christ Good Friday Service is a tradition in the Black Church that brings together the community to commemorate the final words of Jesus Christ while nailed to the cross. Seven preachers, typically men, proclaim the seven last sayings spoken by Jesus from the cross.

25. Watson, Introducing Feminist Ecclesiology, 55.

26. Coleman, Ain’t I A Womanist Too?, 79.

27. Watson, Introducing Feminist Ecclesiology, 54.

28. In late 1990, Lilly Endowment Inc. (an Indianapolis-based private philanthropic foundation) launched the Louisville Institute, based at the Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary. The Pastoral Study Project (PSP) awards pastoral leaders up to $15,000 to pursue a pressing question related to Christian life, faith, and ministry.

29. Watson, Introducing Feminist Ecclesiology, 1.

30. Flunder, “A Womanist Ecclesiology.”

31. Flunder, “A Womanist Ecclesiology.”

32. Flunder, “A Womanist Ecclesiology.”

33. hooks, “bell hooks: Cultural Criticism,” para. 16.

34. Hayes, Digging Deeper Wells.

35. Irie Session first heard the term “practical womanism” from Lyn Norris Hayes when Lyn contacted Irie about using Murdered Souls, Resurrected Lives as a source in her dissertation. The term adds nuance to this work on developing a womanist ecclesiology. In early April 2020, Irie contacted Lyn for permission to use the term in this work. Lyn said she was honored to give permission.

36. Sampson, “Going Live,” para. 1.

37. Turman, Toward A Womanist Ethic, 157.

38. Benbow, “While More Black Churches Come Online,” para. 3.

39. This is a saying attributed to Katie G. Cannon, the progenitor of womanist theological ethics. She was the first Black woman ordained in the United Presbyterian Church and the first woman to earn a doctorate at Union Theological Seminary.

40. Liddle, “Trauma and Young Offenders,” 5.

41. Alexander et al., “Toward a Theory of Cultural Trauma,” 1.

42. Regina Bell-Battle is an R&B and Gospel recording artist. She and her husband co-pastor New Shield of Faith Church in Atlanta, Georgia. They provide nesting space for Rize Community Church.

43. This quote was in the introduction of a sermon preached by Dr. Melva Sampson during the 2019 Festival of Homiletics in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

44. Douglas, Black Bodies and the Black Church, 35.

45. Malcolm X, “Who Taught You to Hate Yourself?” para. 3.

46. Turman, Toward a Womanist Ethic, 172.

47. Turman, Toward a Womanist Ethic, 172.