Читать книгу The Gathering, A Womanist Church - Irie Lynne Session - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Preface

ОглавлениеWomanist Gathering as Public Theology

When I sat down to begin this preface for The Gathering, A Womanist Church, I imagined that I would be reflecting on womanist teaching as a site for womanist church, and womanist church as a site for womanist teaching. I imagined, because I added the course Spirituality and Social Activism in a Time of Trauma to the Maymester summer schedule, that I would bring much of our focus to the Nashville tornado recovery and COVID-19.

Instead, the last week of May 2020 we are buckling under the weight of a(nother) police officer killing another unarmed Black man. George Floyd could not breath under police restaint. George Floyd died a horrible, violent death at the hands of a police officer who had eighteen prior complaints filed against him. Derek Chauvin has since been terminated from his position and arrested—but he is alive.

George Floyd died calling out “Mama.” George Floyd is dead.

His mother, already on the other side of the river, could only receive him; she could not free him from the knee pressed down on his neck. She could not breathe life into lungs as his breath was chocked off by a knee delivering the messages of hate, racism, and death.

George Floyd was murdered. Minneapolis, Atlanta, Detroit, Oakland, Louisville, and cities all across the U.S. are on fire.

We are witnesses to a smoldering liturgy of rage. We need to, we must, gather.

Womanist Pastoral Approach as Public Theology

Womanist pastoral theologians take note of what is happening in the lives of the most vulnerable Black, brown, poor, and disenfranchised bodies and the world. We begin by asking six important questions. What is happening? To whom? How is it happening? Why is this happening? What ethical demands does this situation announce for the pastoral contexts? How are we to respond?

These questions are not asked in linear question and answer process but engage in a recurring cyclical engagement with these pressing questions. In this cyclical or spiral, we deepen the questions by intertwining the realities of social contexts, gender, race, sexuality, gender expression, and education to consider how they are operative forces in communities and individuals’ lives. The Combahee River Collective, a Black feminist collective, in their 1978 “Combahee River Collective Statement,” raised the need for an analysis of the interlocking nature of Black women’s oppression.

The most general statement of our politics at the present time would be that we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see as our particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking. The synthesis of these oppressions creates the conditions of our lives.1

The Black feminist lawyer Kimberlé Crenshaw referred to these simultaneous and interlocking forces operative in Black women’s lives as intersectionality2—looking at the convergence of oppressive dynamics rather than focusing on one, race or gender, as the root of suffering and oppression. Womanist pastoral theologians are also sensitive to the ways in which these forces take up residence in Black psyches as internalized negative reflections and representations of blackness. Womanist pastoral theologians seek to address these sources of social oppression, psychical malformation, and, as a consequence, spiritual harm, simultaneously.

Womanist Ethnography as Pastoral Listening and Public Theology

Womanist pastoral theology that engages the multilayered experiences of Black life requires practices of listening in and out of the explicitly identified pastoral care contexts. Womanist pastoral and practical theologians increasingly turn to ethnography as a method for conveying “thick” narratives that widen the scope of experience. Just as womanist pastoral care requires capacities of empathic listening, organizing narratives, discernment in community, and sustained theological and spiritual practice, womanist ethnography too requires these capacities. In part because womanist ethnography seeks to make the particularity of Black women’s lives the impetus for theological reflection and theological practice. Second, womanist ethnography challenges the assumed hierarchy in models of research that privilege “researcher” over “subject.” In womanist ethnography, Black women who agree to share their stories and experiences also demand that womanist ethnographers come to the space not as an interviewer but as a Black woman who has experienced the same or similar encounters with suffering and resistance. The listening space that womanist ethnography demands is one of fluid mutuality, transparency, and care. It is a space that makes ethical demands on all parties—womanist ethnography is not just about acquiring a “good” interview or story. Womanist ethnography has as its stated aim the gathering and telling of Black women’s lives because Black women’s lives have the capacity to interrogate society, demand justice, celebrate Black life, and make public the relationship between lived experience, justice work, and spiritual and religious practices. Womanist ethnography, then, is not a neutral researcher gathering information from a passive storyteller, but it is a collaboration between a Black woman entering into dialogue with Black women and communities in order to create pastoral, preaching, and ritual practices that embody a public theology grounded in love and the struggle for bringing about a more just world for all people.

Womanist pastoral theology is embodied and expresses a deep theological anthropology that makes the claim that everyone—all people—are created in the image of God. This embodied theological anthropology makes claims about who God is and how God is present and operative in the world. The diversity in all creation is, then, a reflection and expression of the love God has for the world. God is diverse, and this diversity is, or should be, mirrored in communities of faith and in the broader society.

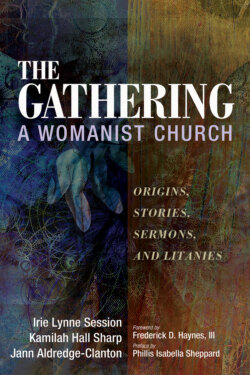

The Gathering, A Womanist Church is a space that embodies its public pastoral theology in song, protest, welcome, worship, and spiritual practices. It takes seriously the need to dismantle the idea that the faith community is to be found solely within the four walls of a building. A womanist public theology stretches itself into the local community and beyond—indeed, into the reaches of cyberspace. The book that Irie Lynne Session, Kamilah Hall Sharp, and Jann Aldredge-Clanton have written is a gift for those who take womanist theology and womanist care seriously. Their commitment to careful theological reflection and a welcoming ecclesiology is evident in their worship and their writing. They have made the vision of womanist church an embodied reality and, therefore, invite others to do the same. I hope others will too.

Rev. Dr. Phillis Isabella Sheppard

Associate Professor of Religion, Psychology, and Culture

Vanderbilt University Divinity School, Nashville, Tennessee

1. “The Combahee River Collective Statement,” para. 1.

2. Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins,” 1241.