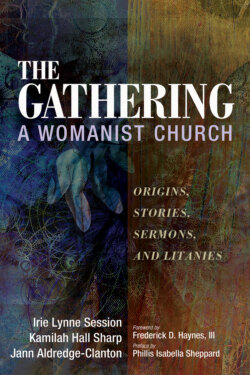

Читать книгу The Gathering, A Womanist Church - Irie Lynne Session - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Defining a Womanist Church

ОглавлениеA womanist church applies womanism and womanist theology to the creation of a faith community. The Gathering, A Womanist Church in Dallas, Texas, is unique as an embodiment of a womanist church. While other churches may draw from womanist theology, The Gathering uniquely applies womanism and womanist theology to the full life and worship of a church community. The Gathering is the only church founded and identified as a womanist church with “womanist” in the title.

Origins, Definitions, and Significance of Womanism and Womanist Theology

Womanism is rooted in Black women’s experiences of struggle, resistance to oppression, survival, and community building. The term “womanist” comes from Alice Walker, literary giant and activist, who is perhaps best known for her book and movie, The Color Purple. She said “womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender.” Alice Walker coined the term “womanist” in her 1983 critically-acclaimed work, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose.1

The creation of this concept was a significant moment for women called to teach religion in academic institutions and to ministry in churches. The term “womanist” is derived from “womanish,” a Black folk expression of mothers to female children suggesting being grown and responsible. Therefore, womanist preachers seek to approach the homiletic text in a responsible manner, learning more than what’s on the surface, and doing the deep exegetical work of looking at the biblical text through a lens of liberation.2

For Black women at the crossroads of academic institutions and the Black church, the 1980s was a time of self-definition. While the term “womanist” was introduced to the world in the 1980s, its meaning encompassed the lived experience of generations of Black women in America, who, like their biblical foremothers, were legally, socially, and even spiritually relegated to the edges of church and society. These women by mother wit, sheer will, and passionate determination charted their own course, rewriting definitions of what it means to be Black, female, and made in the image of God. With the Black Southern expression “you acting womanish,” mamas, grandmothers, aunties, church mothers, and other mothers confirmed, critiqued, and challenged their girl children to insure that they not only survived, but thrived in a world often configured to destroy their creativity, intelligence, and womanhood.3

Definitions of womanism and womanist theology come from a variety of scholars, pastors, and authors. Women and men affirm the transformational significance of womanism.

Dr. Keri Day, currently serving as associate professor of constructive theology and African American religion at Princeton Theological Seminary, asserts that womanism gave her a language, a way of naming her own experience as a Black woman in a “society that does not privilege Black women’s knowledge production process, but rather culturally represents Black women as less or substandard or subhuman in a variety of ways.”4

It was this devaluing of Black women that led to the creation of womanism, according to Rev. Dr. Renita J. Weems, Hebrew Bible scholar and co-pastor of Ray of Hope Community Church in Nashville: “You find yourself in a particular context where there are no Black women’s voices, no scholarship by Black women. You find yourself invisible; your voice is not wanted and not heard. The word ‘womanist’ just caught fire for all of us. It was different from ‘feminist.’ It was our word. It was what our mothers were calling us, meaning that we were sassy, meaning that we were courageous.” She explains that the word “womanist” comes from Black folk Southern culture, “meaning you are bold, you break boundaries, and you don’t mind doing that in order to accomplish what you have to accomplish.”5

Rev. Dr. Teresa L. Fry Brown, professor of preaching at Candler School of Theology in Atlanta, Georgia, affirms the significance of Black women’s voices: “Black women do have voice, even in institutions that said we didn’t, that we were not in history books, that we didn’t have a place in church. It was through engagement over a period of time, meeting other women who were in little silos of institutions or in churches that I learned the importance of voice for all people.” She celebrates womanists as standing on their principles, articulating “the wit and wisdom of Black women” who came before them, and making way for women who will follow them.6

Womanism, that centers Black women’s experience, is essential to the wholeness of church and society, proclaims Rev. Dr. Stacey M. Floyd-Thomas, associate professor of ethics and society at Vanderbilt University Divinity School in Nashville, Tennessee. Womanism is not only what the Black church needs but what America needs “if we’re truly going to embrace the best of who we are as a people who believe that we are all fearfully and wonderfully made and equally created by God.” The mission of womanism is “to make the church whole again and to bring the wisdom that is necessary for us all to be liberated and for none of us to be left behind.” She says that if it were not for “Black women, not only in the church, but in society at large, we wouldn’t have a keen sense of what freedom is.” She describes a womanist: “A womanist is wise. She’s radical, but she’s traditional. She’s self-loving, but she’s engaged. She’s subjective, but she’s communal. She’s redemptive, but she’s critical.”7

Dr. James H. Cone, founder of Black liberation theology, celebrates ”womanist theology and Black woman” as “essential to the very life blood of what we mean by the Black church, the Black religious experience, the Black community.” He commends Black womanist theologians, such as Rev. Dr. Katie Cannon, Rev. Dr. Jacquelyn Grant, and Dr. Delores Williams, for contributing to his “constant development of Black liberation theology.”8

Pastors also draw from womanist theology in developing sermons about race, gender, and class. Rev. Dr. Jacqueline J. Lewis, pastor of Middle Collegiate Church in New York City, states that she leads “with a womanist sensibility” in her multiracial, multicultural congregation. “We’re always thinking about how to story the gospel by any means necessary.” In her congregation “the conversations about race and ethnicity and difference and class take on all kinds of nuances,” she says. “I think especially of Alice Walker’s definition of ‘womanism’ as loving all people, understanding that our cousins are pink and beige and chocolate brown like me. That has been so important to me as I think about rehearsing the reign of God here on earth.”9

Rev. Dr. Frederick D. Haynes, III, senior pastor of Friendship-West Baptist Church in Dallas, tells a story illustrating how womanist theology contributed to changes in his preaching: “I was up preaching, and I made a statement related to Sarah in Scripture. And one of my favorite womanist scholars texted me immediately, ‘You don’t want to say that. That is offensive. That is oppressive.’ The more I took a step back and looked at it, the more it dawned on me that I was a contributor, through that homiletical moment, to oppressing the dominant majority in the congregation. As the senior pastor, I don’t want to contribute to that oppression.” He gives womanism credit for bringing changes: “Womanism helps us reframe our language. Womanism helps us to be more communal. Black women have so infused and energized the Black church. The Black church needs Black women, but more than that, we need Black women out front leading. We need Black women manifesting all of the gifts that they bring to the table.”10

Also emphasizing the need for womanist theology and Black women leaders in the church, Rev. Dr. James A. Forbes, pastor emeritus of The Riverside Church in New York City, states: “The viewpoint of Black women is essential for full understanding of what’s going on in the world as well as what God’s Spirit is trying to stir up among the people. The womanist tradition gave me more of a sense of urgency to lift the Black church out of its sexist orientation.” He asserts that “womanist tradition introduces a critical listening to all things; that’s actually challenging and strengthening to people who can no longer presume affirmation of everything they say.”11

Rev. Dr. Mitzi J. Smith, professor of New Testament at Ashland Theological Seminary in Ashland, Ohio, underscores the necessity of womanist biblical hermeneutics: “Womanist biblical interpretation is necessary because it brings a different set of questions that otherwise may not get answered. Questions that need to be addressed in order that we can live together in a society that respects all voices, that is concerned with the predicament of the least of these among us. We need more and different voices at the table.” Often we live by a biblical viewpoint that “causes us to be oppressive toward others” and is “oppressive to us as well, but we have not learned to think about it more critically,” she says. “Womanism is an approach that privileges the experiences, voices, traditions, and artifacts primarily of African American women, although there are other women of color who call themselves ‘womanists.’ In biblical interpretation womanist scholars use a particular perspective, an African American female’s perspective, privileging our voices. Our voices are not all the same, but we do have things in common. We privilege our concerns, our voices, our traditions, and read biblical texts from that standpoint, from that hermeneutical framework.”12

One of the founders of womanist theology, Rev. Dr. Katie Geneva Cannon, charts a “three-pronged systemic analysis of race, sex, and class from the perspective of African American women in the academy of religion.” In Katie’s Canon: Womanism and the Soul of the Black Community, she calls for an inclusive ethic and reveals how Black women have been “moral agents in the African American tradition that combines both the ‘real-lived’ texture of African American life and the oral-aural cultural tradition vital to African Americans.”13

Another mother of womanist theology, Dr. Delores S. Williams, emphasizes the distinctiveness of womanist theology. In Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk, she explains: “Just as womanist theology has an organic relation to black liberation theology, so does it also have an organic relation to feminist theology.” Although “black male liberationists, womanists and feminists connect at vital points,” there are “distinct differences” precipitated by the “maladies afflicting community life in America—sexism, racism, and classism.” Womanist “god-talk often lives in tension with its two groups of relatives: black male liberationists and feminists.”14

In Womanist Midrash: A Reintroduction to the Women of the Torah and the Throne, Rev. Dr. Wilda C. Gafney also delineates the distinctions between womanism and other liberation movements: “Womanism is often simply defined as black feminism. It is that, and it is much more. It is a richer, deeper liberative paradigm; a social, cultural, and political space and theological matrix with the experiences and multiple identities of Black women at the center. Womanism shares the radical egalitarianism that characterizes feminism at its basic level, but without its default referent, white women functioning as the exemplar for all women.” Womanism is distinct from the “dominant-culture feminism, which is all too often distorted by racism and classism and marginalizes womanism, womanists, and women of color.” Womanism “emerged as black women’s intellectual and interpretative response to racism and classism in feminism” and “in response to sexism in black liberationist thought.”15

Rev. Dr. Monica A. Coleman adds to an understanding of the origin and definition of womanist theology as distinct from other liberation theologies. In Making a Way Out of No Way: A Womanist Theology, she states: “Womanist theology is a response to sexism in black theology and racism in feminist theology. When early black theologians spoke of ‘the black experience,’ they only included the experience of black men and boys. They did not address the unique oppression of black women.” Feminist theologians “unwittingly spoke only of white women’s experience, especially of middle- and upper-class white women. The term ‘womanist’ allows black women to affirm their identity as black while also owning a connection with feminism.” Womanist theology analyzes “religion and society in light of the triple oppression of racism, sexism, and classism that characterizes the experience of many black women.” Womanist theologies maintain “an unflinching commitment to reflect on the social, cultural, and religious experiences of black women.” Womanist theologies are a “form of liberation theology,” aiming for the freedom of oppressed peoples” and adding “the goals of survival, quality of life, and wholeness” for Black women and for all creation.16

White women also affirm the need for womanism. Rev. Dr. Serene Jones, president of Union Theological Seminary in New York City, celebrates womanist theologians for giving “life” to her “blood” and making her “excited about being a theologian.” She expresses the need for more Black women and womanists at Union: “We need more African American women in the student body. We need more funds supporting women to go into ministry. We need more funds for scholarships. We need a whole faculty full of womanists. That would be glorious!”17

Although womanism centers Black women, womanism is not only for Black women. People of all races and genders benefit from womanism and womanist theology. Womanism works for the wholeness of all people and all creation.

Womanism and womanist theology continue to make a significant contribution to theological scholarship and to the lived experience of people. As more scholars and pastors “intentionally do the deeper exegetical work of interrogating the sacred biblical texts to raise up the muted voices of marginalized women, the theological landscape for womanism continues to expand.”18

The Gathering: Defining and Modeling a Womanist Church

Definitions and analyses of womanism and womanist theology, coming from a wide variety of people, provide a strong foundation for a womanist church. This groundbreaking work finds embodiment in a womanist faith community.

As the only church founded and identified as a womanist church, The Gathering is defining and modeling what it means to be a womanist church. The Gathering puts womanism and womanist theology into practice in a faith community. With an expansive mission, an inclusive welcome, an egalitarian organizational structure, womanist co-pastors and ministry staff, ministry partners, womanist social justice priorities, and valuing of all voices, The Gathering embodies a womanist church.

The mission of The Gathering is “to welcome people into community to follow Jesus, partner in ministry to transform our lives together, and to go create an equitable world.” Following Jesus means “responding to the least, last, and lost,” and being “intentional” in ministry to the “marginalized, oppressed, and downtrodden.” The Gathering examines texts to “do the deeper work of seeing the healing, restorative justice, and liberation in the Scriptures.” The Gathering addresses social justice “in a way that raises prophetic voices and issues a rallying cry, speaking truth to power.” The Gathering is a community where people of all genders and races work “together to dismantle the systemic structures that seek to oppress people.”19 The Scriptural foundation for The Gathering is Luke 4:18–19: “The Spirit . . . has anointed me to bring good news to the poor . . . to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free.”

The Gathering welcomes all people. The Gathering demonstrates that a womanist church is not just for women and not just for African Americans, but that a womanist church is for all people—all genders and races and cultures and experiences. This inclusive welcome begins each worship service: “Welcome to The Gathering, A Womanist Church, a community whose faith in Jesus compels us to create worship experiences that address social injustice through womanist preaching and action, to cultivate a healing, learning, and growing community for people who are churched, unchurched, dechurched, hurt by church, and even those who are sick of church. Welcome to The Gathering, followers of Jesus who believe our ministry priorities of pursuing racial equity, LGBTQIA+ equality and dismantling patriarchy, misogyny, and sexism (PMS) are both political and biblical. Welcome to The Gathering, a spiritual community where all are welcome. Really.”

Through an egalitarian organization structure, The Gathering also defines and models a womanist church. Co-pastors, ministry staff members, and ministry partners share in preaching, creating liturgies, worship leadership, pastoral care, and administration.

The Gathering’s co-pastors and staff are womanists, who model a womanist church through their ministries. Their experiences as Black women inform their sermons, music, and other parts of the liturgy. Co-pastors Rev. Dr. Irie Lynne Session and Rev. Kamilah Hall Sharp employ womanist biblical hermeneutics in their preaching and draw from their stories and from the stories of other Black women. In some worship services the co-pastors do what they call “tag-team preaching,” both delivering short sermons, emphasizing their equal partnership. Rev. Dr. Irie defines a womanist as a “Black woman who is progressive in her theology, courageous in her social justice advocacy and activism, fierce in her love of self and others, and actively engaged in work that contributes to the survival and wholeness of all people, Black communities in particular.” Rev. Kamilah describes a womanist as caring “about people and about community” and looking “for ways to make the world better by using the experiences of Black women as a starting point.”20 Rev. Winner Laws, minister of congregational care and spiritual support, says that as a womanist, she is “committed to sharing narratives of Black women’s experiences to empower all people spiritually and to be a voice for those on the margins to find their place in the creation story.” Faith Manning, minister of music, asserts that womanism “is the liberation of Black women,” and that “when we liberate Black women we liberate the world.”21

Ministry partners join to embody The Gathering as a womanist church. In worship services, ministry partners participate in many ways, such as leading Communion meditations and prayers, singing in a choir, writing and leading litanies, greeting people, making announcements, and assisting with technology for livestreaming the services online. Ministry partners also share in the administrative work of The Gathering, and in planning and implementing ministry projects. Based on the belief that partnership in ministry creates “a sense of belonging, deeper connection, and vibrancy” in a faith community, The Gathering invites people to be ministry partners, instead of “members.” Ministry partners use their gifts to help “fulfill the God-given vision” of The Gathering. They use their voices, networks, platforms, and voting voices to partner in addressing the social justice priorities of The Gathering—racial equity, LGBTQIA+ equality, and dismantling PMS (patriarchy, misogyny, and sexism). Ministry partners are consistent in participating in worship celebrations in person and/or online, consistent in financial support of The Gathering, and consistent in sharing their “God-given talents with The Gathering.”22

The Gathering also models a womanist church through social justice priorities of racial equity, LGBTQIA+ equality, and dismantling PMS (patriarchy, misogyny, and sexism). The Gathering creates “worship experiences that address social justice issues through womanist preaching and action.” Other missional priorities of The Gathering are to “be an authentic and compelling faith community for people who feel a disconnect with the institutional church; be a healing, learning, and growing fellowship for persons marginalized in society; dismantle patriarchy one womanist sermon at a time; discover together how the ministry of Christ calls us to welcome all, really.”23

In addition, The Gathering defines a womanist church through the innovative time in each worship service called “Talk Back to the Text.” This womanist practice values all voices. After each sermon, people in the congregation have an opportunity to make a comment or ask a question about the text and the sermon. The preacher or preachers, if they have preached “tag-team” sermons, will then respond and give opportunity for others to respond. This practice includes not only people attending The Gathering in person, but also those attending online. People in the online congregation can send their comments and questions. This inclusive, egalitarian practice gives everyone an opportunity to participate. A person does not have to be a ministry partner or regular in attendance to make comments and ask questions. “Talk Back to the Text” is open even to first-time visitors. A womanist church includes and values everyone, contributing to the wholeness of all.

Womanism and womanist theology have brought transformation to academic institutions, churches, individuals, and society. A womanist church expands this transformation through the power of community and ritual experience. A womanist church community practices and embodies womanism and womanist theology. Worship services in a womanist church convert our imaginations as well as intellects. Through the power of womanist liturgies, womanist theology takes root in our hearts and souls. Our actions also change as the creative, liberating rituals permeate our whole beings. A womanist church has great power to touch the heart and change the world.

Our world stands in urgent need of the transformation a womanist church brings. Although The Gathering is the only womanist church at this time, we believe the Spirit will use The Gathering to give birth to many more womanist churches. The Gathering moves forward to fulfill our unique call to define, model, and create a womanist church.

1. Walker, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens, xi−xii.

2. “Who Is the Womanist?” The Gathering, para. 2.

3. Womanist Institute, “What Manner of Woman.”

4. Womanist Institute, “What Manner of Woman.”

5. Womanist Institute, “What Manner of Woman.”

6. Womanist Institute, “What Manner of Woman.”

7. Womanist Institute, “What Manner of Woman.”

8. Womanist Institute, “What Manner of Woman.”

9. Womanist Institute, “What Manner of Woman.”

10. Womanist Institute, “What Manner of Woman.”

11. Womanist Institute, “What Manner of Woman.”

12. Smith, “Womanist Biblical Hermeneutics.”

13. Cannon, “A Deeper Shade of Purple,” para. 11.

14. Williams, Sisters in the Wilderness, 158.

15. Gafney, Womanist Midrash, 2−6.

16. Coleman, Making a Way, 6−11.

17. Womanist Institute, “What Manner of Woman.”

18. “Who Is the Womanist?” The Gathering, para. 3.

19. “Who We Are,” The Gathering, para. 1−8.

20. “Meet the Preachers,” The Gathering, para. 2−4.

21. “Gathering Staff,” The Gathering, para. 2−4.

22. “Partner. Gather Online. Support,” The Gathering, para. 1−5.

23. “Meet the Preachers,” The Gathering, para. 8−9.