Читать книгу John Stott’s Right Hand - J. E. M. Cameron - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Biographies are by no means always welcome. A E Houseman resolutely refused assistance to a would-be biographer. Robert Bridges, Poet Laureate, destroyed much of his personal archive to frustrate any future attempts to write his Life. The problem can become even more acute if the subject is still alive when the book appears. Robert Runcie, Archbishop of Canterbury, was so dismayed by what his biographer had recounted, that he famously wrote to the author: ‘I have done my best to die before this book is published. It now seems possible that I may not succeed...’ When I was asked to write John Stott’s life, by his advisory group of elders, I naturally consulted him about it. He firmly hoped that it would be for posthumous publication, and only as the work proceeded was he persuaded to change his mind. His reason for disliking the proposal had all to do with his characteristic humility, his rooted dislike – one could say almost fear – of self-aggrandizement. He cited to me, with distaste, celebrity autobiographies with titles like Ego or Dear Me. It is not a groundless misgiving. Even in the autobiography of so staid a man as Anthony Trollope, the words ‘I’, ‘me’, ‘my’, ‘myself’ appear 50 times on a single page.

It seems safe to assume that the name of John Stott will already be known to readers of this book. Whether this is so or not, much of who he was, and of a life spent (‘poured out’ might be a more descriptive phrase) in the service of his Master, Jesus Christ, is to be found in the pages that follow. They also contain a description of Dr Billy Graham’s first major Greater London Crusade at Harringay in 1954, in which John Stott played a significant part, and of the lifelong friendship forged between the two men. I remember having to make a train journey on the morning after the opening night of the Crusade, and avidly buying up a selection of newspapers at the station bookstall, to read the press accounts. Paper after paper carried the story on the front page – not normally given to anything ‘religious’ – and Billy Graham’s name was in every headline. That railway journey came to my mind when I heard Billy Graham, on some later occasion, raise the question of whether there would be newspapers in heaven. It was not a very serious supposition, but it was to make a serious point. ‘If there are newspapers in heaven,’ he told his audience, ‘it won’t be my name that is in the headlines.’ By the values of the world, the values of the kingdom of heaven will always seem topsy-turvy, as Jesus had to explain to his disciples at that Last Supper.

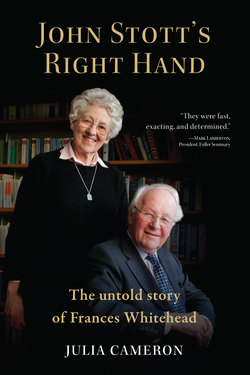

It would be no surprise to find that many readers who know the names of John Stott and Billy Graham know little, if anything, of Frances Whitehead, who is the subject of this book. I like to think that if there should be a ‘New Jerusalem Daily Press’, the names of Billy Graham and John Stott would indeed be in the headlines, and ‘Frances Whitehead’ up there beside them. I do not need to elaborate this, for all that follows in these pages makes crystal clear that John Stott could not have achieved the work he did without Frances at his elbow.

You will read, quite early on, of her conversion to Christ, for which her younger days were to leave her not unprepared. By the age of 18 she had known two close bereavements; she must also be one of the last generation to learn the outline of her faith from the Catechism in the Prayer Book! From secret work in the war as a young mathematician, she came in the providence of God to work for the BBC, just across the street from All Souls Church, which was to become the centre, not just of her work, but of her life, for the rest of her days. Support for John Stott, as she looked back on it, was indeed ‘a life, not a job’. But this Introduction is not really the place to cherry-pick incidents and episodes from that job and life. For that, you will want to move quickly on into Julia Cameron’s thoroughly-researched account, from an insider’s privileged viewpoint, in the chapters that follow.

But you must allow me to endorse, from my own experience, all that Julia writes and all that she quotes from John Stott, from his study assistants – indeed from all who knew Frances – of her gifts, pastoral and personal, as well as financial, administrative, editorial. In everything that touched John Stott and his work, she was enabler, supporter, adviser, encourager, as well as – to borrow terms from the media – gatekeeper and anchorman. With Frances in control, no one was going to disturb John Stott’s prayerfully planned programme without due cause; and any crisis that might dare to raise its head would quickly and resolutely be resolved.

This book, therefore, is much more than a personal tribute. It is that, of course. The late Penelope Fitzgerald, biographer and Booker prize novelist, gave it as her opinion that novels should be about those whom you think are sadly mistaken, but that ‘you should write biographies of those you admire and respect.’ This is clearly such a work. But it is also an important addition to the history of a period in which the evangelical stewardship of the gospel was undergoing expansion and renewal, written from the perspective of those involved. And that makes this biography a shining exception to the opening sentence of this Introduction. Later in the book you can read of how, when All Souls rectory was a bachelor establishment of curates, students and other residents, some wag combined the words ‘rectory’ and ‘vicarage’ to name it ‘The Wreckage’. It would have been better to combine them another way, so that all who lived and worked there in the days of John Stott and Frances were sharers in ‘The Victory’!

Timothy Dudley-Smith

Ford, Wiltshire