Читать книгу John Stott’s Right Hand - J. E. M. Cameron - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

Memorial service at St Paul’s Cathedral

It was a cold, bright morning in central London. Around 9.30 a.m., as rush-hour traffic was still moving very slowly, Frances Whitehead, aged 86 and elegantly dressed in a mid-blue suit, got off a bus in Fleet Street, deciding instead to walk the remaining short distance over Ludgate Circus and up Ludgate Hill to St Paul’s Cathedral. She was accompanied by Mark Labberton, one of John Stott’s former study assistants. The occasion was the Memorial Service for John Stott, who had died on 27 July 2011.1 In her bag was a finely-honed script.

They passed the City Thameslink Station on their right, with the Old Bailey off to the left. From the top of the hill they could see that hundreds of people had already begun to arrive and were queuing outside the Cathedral; it was clear that the seating would be full to capacity. Eighteen hundred places had been booked online very quickly after they were made available; a further two hundred had been kept back for people queuing on the day. The queues were abuzz with conversations and reunions.

St Paul’s Cathedral is where John Stott aged 24, having just finished at Cambridge, was ordained in December 1945. He was then about to begin his ministry as assistant curate at All Souls Church, Langham Place, in London’s West End. He had grown up in Harley Street, the son of a consultant, and from his early years, he and his younger sister were taken to All Souls Church by their nanny. His earliest memory of the All Souls rectory at 12 Weymouth Street, where he himself would later live for over 50 years, was of his Sunday school days in the mid 1920s, when he spent more time outside the classroom than inside it, excluded for terrorizing the girls with his toy guns and plastic daggers. A very different John Stott would emerge twenty years later as he stood in this great Cathedral to take serious and weighty ordination vows.

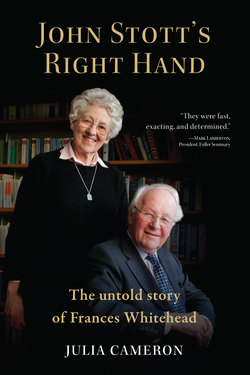

It was in the mid-1950s, as a young Rector, that he invited Frances Whitehead, a member of the congregation, to become his secretary. As history will bear witness, it would be hard now to imagine John without Frances; ‘Uncle John’ without ‘Auntie Frances’, as they became known. On this January morning in 2012, at the Memorial Service for one of the twentieth-century giants of the faith, Frances Whitehead was, at John Stott’s stated request, to give the opening tribute.

When Frances reached the Cathedral, she went straight in for the usual voice checks. Those taking part had seats reserved for them on the front row, beneath the dome. At 10.45 a.m., the Cathedral staff opened the huge doors. People gradually filled the building, showing their entrance tickets, printed out at home like boarding passes. As they continued down the aisle in the long nave, everyone was handed the Order of Service. It showed John Stott’s face in silhouette on the cover, illustrating a clear connection between him and his ‘mentor’, the great Charles Simeon of Cambridge.2 As the line moved down the aisle, virgers3 ushered people to seats, first filling the rows beneath the huge dome and gradually working backwards to the West door.

No stoles. No mitres

There was a sense of reverence, of thankfulness, and of awe at Christopher Wren’s marvellous imagination, and at the beauty of craftsmanship brought to its execution. For those who had watched the wedding of Prince Charles and Diana Spencer on television, or the Queen’s 80th birthday and Diamond Jubilee, the striking black-and-white floor with its stark starburst mosaic under the dome held a strange familiarity.

What aesthetic richness in the stately Corinthian pillars, intricate artwork and massive memorials; and for those who looked up, in the gloriously-painted dome ceiling, depicting scenes from the life of St Paul. Few looked up for very long. For, for all the grandeur of the setting, and formality of the occasion, there was no sense of stuffiness. Here was an historic gathering of friends from around the world; there was news to share, there were questions to ask, and greetings to be sent to people too frail to attend. Those taking part soon left their seats on the front row to greet old friends. Then, as the start of the service drew close, the All Souls Orchestra began to play, filling the Cathedral with works by Handel, Elgar and Guilmant. Frances once more took her seat, next to Jane Williams, the wife of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

The congregation rose to sing the Processional hymn: Charles Wesley’s ‘Jesus! The Name high over all’ to the tune Lydia. This exaltation of Christ, expressing a deep desire for wholehearted service of Christ, had been chosen by John Stott years earlier.

Jesus! The name high over all

In hell or earth or sky;

Angels and men before it fall

And devils fear and fly.

The Procession made its way slowly down the aisle. As the hymn concluded, the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, and the Bishop of London were standing beneath the dome, facing the congregation. Something was different; something was missing, yet it took a moment to realize what it was. Here were the most senior Archbishops in the worldwide Anglican Communion, at a service in one of the best-known Cathedrals in the world. Yet they were not dressed in their usual ecclesiastical regalia; they were dressed in plain convocation robes. There were no stoles; no mitres; and the two Archbishops carried no crooks. This was surely out of honour for an evangelical statesman who never sought high office.

The Revd Canon Mark Oakley, Canon in Residence of the Cathedral, read the Bidding:

...We remember with joy and thanksgiving the life of John Robert Walmsley Stott, a minister of the gospel, beloved pastor, Bible scholar, mentor and friend. His simple life of study and prayer, preaching, writing and discipling, helped shape the face of a 20th-century evangelical faith in Britain and around the world. He was valiant for truth, even when that was unfashionable ... John eschewed public accolades and ecclesiastical preferment and would be embarrassed by any service that dwelt on him or his achievements rather than pointing to his Saviour, crucified, risen and ascended...

The sheer dimensions, and the formality, of St Paul’s Cathedral require a range of staff and servers. Wandsmen – servers dressed in robes and bearing wands – come to collect those who are about to address the congregation, and then lead them back to their seats afterwards. A wandsman duly came to collect Frances. Led by the wandsman, Frances approached the lectern when the Bidding Prayer ended. Michael Baughen, who had succeeded Stott as Rector of All Souls in 1975, introduced the tributes. ‘Frances Whitehead’, he said ‘knew John better than almost anyone.’

Frances Whitehead’s opening tribute

Those knowing the inner workings of John Stott’s office in Weymouth Street had a shrewd sense of Frances’s part in his ministry, but there were doubtless many in the Cathedral that morning who did not know. This in itself bore testimony to the spirit she brought to her role. Pressing her fine gifts into service, to enable John to serve Christ more effectively, she became a major means of multiplying his ministry. He could rely on her, and he did rely on her.

Frances laid her notes on the lectern and looked up. She spoke with authority, winsomeness and clarity. Few indeed could have known John Stott as well as she did:

Many tributes from all over the world have already been paid to John Stott. So I have asked myself what could I say that has not already been said, by way of gratitude to God for John’s life. As for me, I know nothing but thankfulness for John himself, for his godly example, his concern for others regardless of race, colour or creed, and his faithful biblical preaching through which the light of Christ had first dawned on me.

Because I worked alongside him as his secretary for 55 years, perhaps I more than anybody can testify to the fact that, in his case, familiarity, far from breeding contempt, bred the very opposite – a deep respect, and one which inspired faith in the one true God. The more I observed his life and shared it with him, the more I appreciated the genuineness of his faith in Christ, so evident in his consuming passion for the glory of God, and his desire to conform his own life to the will of God. It was an authentic faith that fashioned his life – it gave him a servant heart and a deep compassion for all those in need, one that moved him to keep looking for ways in which he might be of encouragement and support to others, sharing his friendship and his own resources.

To work with John was to watch a hard-working man of great discipline and self-denial, but at the same time to see a life full of grace and warmth. His standards were high and he took trouble over all that he did; nothing was ever slapdash. He was consistent in every way and always kept his word. Although so gifted himself, he never made me feel inferior or unimportant. Instead, he would share and discuss his thoughts and plans with his study assistant and me, listening to our contributions, and eager to ensure consensus between the three of us – the ‘happy triumvirate’ as he would call us. So I found him easy to please and ever grateful for one’s service.

The Scriptures lay at the heart of all John’s teaching and preaching. His ability to interpret them was not simply a matter of the intellect, but of a heart full of love for Christ, and a longing to serve him faithfully, no matter what the cost in human terms. For he believed and submitted himself to the sovereignty of God and the Lordship of Christ in his own life – and he accepted the authority of the Bible as the word of God, regardless of ridicule by some.

Indeed, John taught and practised what he believed, and I thank God for the way he pointed me constantly to Jesus. ‘Don’t look at me’, he would say. ‘Look at Jesus and listen to him.’ But he also demonstrated the truth of what he was saying by his own example of obedience. This was the powerful magnet that drew people to put their faith in Christ as the Son of God and Saviour of the world. He believed that Christ lived on earth, died on the cross for our salvation, and will come again one day in glory. He believed that death is not the end, and that there will be a new creation in which we may all share, through repentance and faith in Jesus.

Thank God that John deeply believed all these truths, lived in the light of them, and maintained them, right to the very end. John’s life was a wonderful example of what it means to be a true Christian – and what a blessing he was to all those who were privileged to know him.

As Frances Whitehead attested, John Stott ‘deeply believed all these truths, right to the very end’. The Rugby schoolboy, converted to Christ aged 17, had finished well. Frances picked up her script and stepped away from the microphone. Her place at the lectern was taken by the Most Revd John Chew, Archbishop of South East Asia.4

Called, chosen and faithful

Not surprisingly, given the centrality of Scripture in his ministry, Stott had wanted the Bible to be clearly handled in the Memorial service. His choice of a preacher was one of his oldest friends, the hymnwriter Timothy Dudley-Smith.5 The sermon was based on Revelation 17:14 ‘Jesus is Lord of lords and King of kings, and those with him are called and chosen and faithful’. Eyes were directed to the risen, glorified Christ, and the sermon finished with a question often posed by John Stott as he concluded an address. Having laid out the historic facts of the gospel record, and a clear apologetic for its credibility, he would land his talk on the personal level, in a way which demanded a personal response. The Bishop did the same, finishing with Stott’s familiar question: ‘How is it between you and Jesus Christ?’

The service closed with Timothy Dudley-Smith’s much-loved hymn ‘Lord, for the Years’. Noel Tredinnick once more raised his baton and the All Souls Orchestra played the introduction as the congregation stood. With conviction, 2,000 voices sang:

Lord, for the years your love has kept and guided,

Urged and inspired us, cheered us on our way,

Sought us and saved us, pardoned and provided,

Lord of the years, we bring our thanks today.

Frances had spoken of John Stott’s integrity and consistency, and of his self-discipline and his obedience. His life was an example to follow; for like the Apostle Paul, John followed Christ’s example. The final verse of the hymn summed up the prayerful aspiration of all as the service drew to a close:

Lord, for ourselves; in living power remake us,

Self on the cross and Christ upon the throne;

Past put behind us, for the future take us,

Lord of our lives, to live for Christ alone.

The congregation sat or kneeled as the Archbishop of York and the Bishop of London led the final prayers, then the Archbishop of Canterbury pronounced the blessing. As these senior leaders of the Church of England processed out, one wondered if they would ever be seen again wearing such little emblem of high ecclesiastical office.

Around the time of Frances Whitehead’s appointment in 1956, John Stott had been approached by the board of what is now the London School of Theology, to become its Principal. This was not the only such invitation he would receive. A friend wrote to him: ‘If I were the Archangel in charge of “postings”, I should leave that said Rector where he is as long as possible.’6 That Archangel did indeed leave John there, but he did more. For he had been tracking the young woman who came to London in 1951, aged 26; a woman with a fine mind and an unusual capacity for hard work, not yet a committed Christian, but for whom God had a particular calling.

John Stott’s death had been announced on the BBC news ticker, and his UK press obituaries commanded more space than would normally be given to a serving cabinet minister.7 Many tributes appeared on social media and 30 thanksgiving services were held across the continents. Stott’s impact was such that in April 2005, TIME magazine named him as one of the ‘100 most influential people’ in the world. Under God he had exercised this ministry with barely any support staff. Without, as John called her, ‘Frances the omnicompetent’, such effective work on a range of fronts at once would not have been possible. Frances Whitehead’s story will now be told.

1. John Stott’s funeral had taken place on 8 August 2011 in All Souls Church, Langham Place, London. That was a less-formal service for the church family and for friends. His ashes were buried on 4 September 2011 in the churchyard in Dale, close to his writing retreat, The Hookses. (See pp121 ff.)

2. Charles Simeon (1759–1836), Vicar of Holy Trinity Church, Cambridge, was famously caught in a series of silhouettes by Edouart Augustin. While divided by nearly 150 years, John Stott was, in a sense, tutored by Simeon in expository preaching.

3. The spelling ‘virger’ is used by St Paul’s.

4. Tributes in the service were brought from senior leaders in all continents. To listen, go to johnstottmemorial.org

5. Timothy Dudley-Smith, retired Bishop of Thetford, was a friend from Cambridge days and John Stott’s authorized biographer. To listen, go to johnstottmemorial.org

6. In a letter from Douglas Johnson, founding General Secretary of the Inter-Varsity Fellowship, now UCCF. For the full quote see Timothy Dudley-Smith John Stott: The Making of a Leader (IVP, 1999) p321.

7. The Times, The Telegraph, The Independent and The Guardian all carried obituaries on Friday, 29 July 2011.