Читать книгу John Stott’s Right Hand - J. E. M. Cameron - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

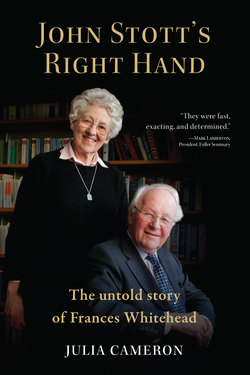

Frances must have known about me for quite some time before I got to know her. Having heard John Stott often as a student in the late 1960s, I first met him in person in 1978 at the National Evangelical Conference on Social Ethics. With my newly-minted doctorate in the economic ethics of the Old Testament, I had been asked to give one of the Bible expositions. From then on, John Stott (the convenor of the conference) took an interest in the career that my wife Liz and I were embarking on, in ordained pastoral ministry, theological teaching and international mission. That involved a measure of correspondence between John and us over the ensuing years – correspondence which, from John’s end, Frances must have typed. Doubtless I was one among several hundred names in her address book and filing cabinet… In those days ‘Frances Whitehead’ was a phenomenon one heard about but never saw, but whose existence was manifestly evident in John Stott’s phenomenal output.

When Liz and I returned from five years in India in 1988, John invited me to be a trustee of the Evangelical Literature Trust. That meant regular board meetings in the basement of 12 Weymouth Street, entrance to which was by way of Frances’s office. And Frances herself was one of the trustees and the secretary. So I got to meet this ‘phenomenon’ more regularly. There was always a lovely warmth of welcome for all of us at those meetings. But I recall how over the decade or so that followed, the welcomes became more demonstrative – earlier formality gave way to ever more embracing hugs (from both of them) and a kiss (from Frances). For two such quintessentially unique individuals, with such backgrounds and life-stories, their capacity for genuinely loving and interested friendship was astonishing. In John’s case it was fostered by his international travel and face-to-face meetings. For Frances it all happened from a small office in central London. Yet, from there she participated in the global embrace of John’s friendships.

What strikes me most, as I read Julia Cameron’s beautifully-crafted biography of Frances, is the awesome providential sovereignty of God. Here were two individuals, with some similarities in their background and upbringing in England between the first and second world wars, one very urban and the other deeply rural – quite unknown to each other. Two people with very different life experiences and mixtures of personality traits, gifts, interests and competences. And yet, by a series of what might look like coincidences, or random choices (a lunchtime walk; a visit to an art-gallery), God engineered their coming together into a working partnership in which the gifts and energies of both could be fully deployed – serving each other in multiple human and hum-drum matters, and serving God’s mission in their generation. It was a partnership in ministry with the gracious and sovereign hand of God on its origins, its operations, and its outcomes.

Church history will record the name of John Stott till the Lord returns. But the story of John Stott would have been very different, and simply could not have been what, by God’s grace, it became, without the complementary ministry of Frances Whitehead – the lady behind the legend. John never wanted to be known as anything more than a humble servant of God. Neither does Frances. Every Bible reader knows Jeremiah, while few know about Baruch, his secretary. Baruch was a servant of the servant of the Lord. That was the role that Frances gave her life to fulfil. It was, as she says, ‘a life, not a job’. Yet even Baruch has a small chapter to himself in the big book that carries the prophet’s name. So in the midst of the many books by John Stott and about John Stott, it is altogether right and worthy that there should be one book dedicated to the woman who served her Lord by serving him.

Chris Wright

International Ministries Director, Langham Partnership