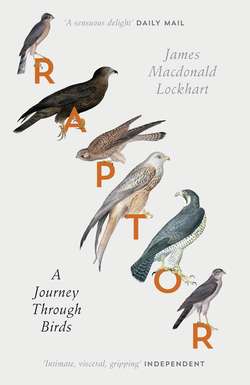

Читать книгу Raptor: A Journey Through Birds - James Lockhart Macdonald - Страница 11

Golden Eagle

ОглавлениеOuter Hebrides

Before the long walk to London, before university in Aberdeen, before birds had entered his life, William MacGillivray learnt to shoot a gun. The first shot he fired – his uncle supervising, leaning over him, telling him to keep the butt flush against his shoulder, to anticipate the recoil – he blasts a table, hurries up to it afterwards through the bruised air to inspect the splintered wood. Getting his eye in, his uncle nodding, encouraging. With the second shot, he brushes a rock pigeon off the cliffs, flicking the bird into the sea. His third shot hits two pigeons simultaneously, sets them rolling like skittles. Recharging his gun with buckshot, peering over the cliff, searching for the pigeons bobbing in the thick swell. Let the barrel cool, William. His uncle saying this and as he says it MacGillivray tests the barrel with his finger and flinches at the heat, and in that instant the gun worries him, becomes something more physical, and his shoulder wakes to the ache of the recoil. So by the time he fires the fourth and fifth shots he is too wary of it, of the power of the thing, his body squinting, flinching when he squeezes the trigger. And he pulls the shots wildly. His uncle lightly ribs him at this: You even missed the mountain! Some hours later, when the barrel has cooled, when his anxiety has cooled, MacGillivray fires the gun again. This time he hits and kills a golden eagle.

The first time I fired a gun? I must have been the same age as MacGillivray was, ten or eleven, staying at a friend’s house on a farm. We drove out with his father one evening in a pickup truck, bumping slowly along the side of a wood, scanning the brambly undergrowth. At first I could not find the rabbit, though my friend kept pointing to it, only a few feet from the truck; puffy, weeping eyes, hunched in on itself. A crumpled, shuffling thing. It had not noticed us. Its eyes looked like they had been smeared with glue. A mixy, his dad said; here, put it out of its misery. He turned the engine off, draped an old coat over the open window, a cushion for me to lean the rifle on. Then, like an afterthought, as if he felt it would stop the gun shaking in my hand, he pulled the handbrake up; its wrenching sound like a shriek inside the truck.

So MacGillivray waits for the ache in his shoulder to subside. Then sets about gathering what he will need to shoot the eagle: a white hen from his uncle’s farmyard, some twine, a wooden peg, a pocketful of barley grain, newspapers, the gun. He walks out of the farm and up the hill. When he reaches the pit that has been dug into the side of the moor, he ties the hen’s leg to the twine and fastens the twine to the wooden peg. He pushes the peg into the ground, sprinkles some of the grain beside the hen and primes the gun with a double charge of buckshot. Then he retreats to the pit with its roof of turf. When he enters the hide it is as if the moor folds him into itself. He can keep an eye on the hen from a peephole cut into the wall of the pit. He starts to read the newspapers. Rain seeps through the roof and the damp paper comes apart when he turns it. He finds himself rolling scraps of newspaper into balls of mush in his palm until it looks as if he is holding a clutch of tiny wren’s eggs. Outside he can hear the hen shaking the rain off itself.

He is dozing when he hears the hen scream. He scrambles to the peephole and there is the eagle fastened to the back of the chicken. The eagle is so huge it has shut out the horizon with its wings. The hen looks as if it has been flattened. MacGillivray hurries to pick up the gun, takes aim, and fires. But he has overloaded it with shot and the recoil shunts him backwards, the butt smashing into his cheek. He cannot see what has happened – if he has hit anything – as smoke from the gun has engulfed the eagle and the chicken, so he pushes through the heather doorway of the hide and rushes up to the target. The shot, he sees, has entered the side of the eagle and killed the great bird outright. The hen, amazingly, is still alive, trying to hobble away. So this is an eagle, he thinks; it is nothing wonderful after all … Gun in one hand, hen in the other, he throws the eagle over his back and brings its legs down on each side of his neck. Then he sets off back down the hill, wearing the huge bird like a knapsack.

Eagles started to make themselves felt while I was searching for merlins in The Flows of Caithness and Sutherland. There was the eagle’s plucking post – that huge flat-topped boulder, littered with bones – I came across far out on the bog. Now and then, too, I saw eagles – often a pair – rising high over the mountains to the west. It was hard not to act on these sightings, to stay on the flow and not follow the eagles into the west. Once, watching the male merlin rising above the burn, in the far distance, perhaps a mile away, I saw an eagle circling high over the moor. I liked the symmetry in that moment, lining up the smallest raptor in these islands with the largest. A telescopic projection, the merlin’s wingspan magnified onto the rising eagle, pointing the way to the next stage of my journey. So I left the merlins above their burn in the Flow Country and followed that eagle into the west, to spend a week amongst the mountains of Lewis and Harris, William MacGillivray’s stamping ground, the place where he shot the golden eagle on that morning of steady drizzle.

What became of the white hen and the eagle that he shot? When MacGillivray came down off the hillside with the eagle slung over his shoulders the whole village came out to greet him. It looked, at first, as if he was carrying a bundle of heather on his back. Surely the boy could not have shot an eagle? MacGillivray’s uncle proud as punch, one eagle the fewer to worry his lambs. And because then MacGillivray knew no better, because birds had still to enter his life, he did not count the eagle’s quills, did not measure its bill, did not dissect it to see what it had eaten. Instead, the eagle was dumped on the village midden. The hen, miraculous escapee, lived on, reared a brood, was then eaten.

The villagers call MacGillivray Uilleam beag (Little William). He comes to live among them, on his uncle’s farm on the Isle of Harris, when he is three years old. Before Harris, before he acquires his Gaelic name, there is not much to go on. MacGillivray’s father, a student at King’s College in Aberdeen, leaves soon after William’s birth in January 1796, joins the army and is killed fighting in the Peninsular Wars. MacGillivray’s parents are not married and his mother, Anne Wishart, is never mentioned again. So his birth is a hushed, awkward thing and the boy is bundled away to be brought up by his uncle’s family on their farm at Northton in the far south-west corner of Harris. When he is eleven, MacGillivray leaves the farm for a year’s schooling in Aberdeen before enrolling at the city’s university. Always returning from Aberdeen by foot to Harris for the holidays; a journey of over 200 miles, walking across Scotland’s furrowed brow, at ease within his solitude, hurrying to catch the Stornoway packet out of Poolewe, back home across the Minch.

After a day of rain and fuming cloud I found the eagles hunting at first light. I saw their shadows first, moving fast over outcrops of gneiss, the grey rocks glancing in and out of shade. The rush of their shadows betrayed the eagles; only storm clouds move that fast over the land. They were a pair and hunting low over low ground at the north end of the glen. I climbed a tall boulder, an uprooted molar, and perched on its flat top to watch.

The sun that morning was out of all proportion, suddenly huge and close. And what that sun did to the eagles … It found their hunting shadows and, as it rose, lengthened them like ink spills along the bottom of the glen. It found and lit the crest of gold down the back of the eagles’ necks in a clink and flash of bronze. And it lasted only a few seconds. But you hardly ever see that in a golden eagle, you are never close enough to see the bird’s golden hue, to the extent that you wonder how the bird got its name at all, when most of the time all you see is a great dark bird which MacGillivray knew simply as the Black Eagle. But there it was below me, the huge bloodshot sun finding and lighting up the delicate golds brushed into the eagle’s nape.

Bird of silence and the clouds, what sort of hunter are you? We tend to exaggerate you out of all proportion. Stories of you driving adult deer over cliffs, lifting human babies when their mother’s back is turned, fights to the death with foxes, wildcats, wolves … In the city where I work there is a swinging pub sign with an image of an eagle, talons clasped around a human child, flapping heavily, bearing the infant away through the cobalt blue. You must forgive us our silliness, our intolerance. For when we meet you your sheer size is dizzying. Seton Gordon once mistook a golden eagle for a low-flying aeroplane. Even MacGillivray, who so often saw eagles in the Outer Hebrides, was stunned when once, at the edge of a precipice, a huge golden eagle drifted off a few yards in front of him while a great mass of cloud rolled over the cliff. MacGillivray was close enough to almost touch the eagle and so struck by the bird’s presence, he shouted out from the top of the cliffs: Beautiful!

In reality a golden eagle could never lift something as heavy as a human baby, let alone a child. Even a mountain hare often needs to be dismembered, a lamb broken in two, before an eagle can carry a piece of it away. Gordon once wrote to a Norwegian lady after he heard about a radio broadcast she had made recounting her experience of being carried away by an eagle as a child. Gordon wrote to the woman asking if he could quote her experience in his book. She replied saying that she might consider his request on payment of a £25 fee.

Up on the bealach there is a movement along the ridge to the west: long-fingered wings, an eagle gliding just a few feet above the ridge. Then another eagle joins it: the male, noticeably smaller than the female.

Close up, when he was observing eagles from a hide – as Rowan did with his merlins – Gordon could tell the difference between the male and female golden eagle by the compact tightness of the male’s plumage. But at a distance it is hard to distinguish between the sexes until the pair come together, and then the size difference is obvious, as it is with many other raptors, particularly the falcons, hawks and harriers, where reversed size dimorphism (when the female is larger than the male) is a characteristic of the species, in contrast to non-raptorial birds where the male is usually the larger. Some of the male golden eagles MacGillivray saw over these mountains appeared so small he thought for a while that another distinct species of eagle existed in the Outer Hebrides, yet to be identified, cut off from the world in these remote hills.

Reversed size dimorphism is most pronounced in those raptors that hunt fast, agile prey. So, for example, the greatest size difference between the sexes is found in the sparrowhawk, where the female is nearly twice the weight of the male. By contrast, there is far less size variation between the sexes in those raptors that are insectivorous or feed on slow-moving prey, and no difference at all in carrion-feeding vulture species. Female raptors must substantially increase their fat reserves in order to breed successfully. This increase in weight does not equip them well to pursue and catch their quick, elusive prey. However, male raptors (those that hunt avian prey especially) must remain as small and light as possible in order to hunt successfully to provide food throughout the breeding season for the female and their brood. Size dimorphism is reversed in many birds of prey because the male cannot afford to become too big; he needs to maintain an efficient size and weight in order to hunt efficiently. The female can afford to become bigger because, during the critical breeding season, she does not hunt as prolifically as the male. This hunting respite allows her to lay down sufficient fat reserves to produce and then incubate her eggs. There is the additional advantage that the female’s larger size better equips her to defend the nest against predators.

What a strange grey beauty these mountains have (MacGillivray compared them to a poor man’s skin appearing through his rags). The land scraped bare, the moor a craquelure of gneiss. The warm rocks smoking in the rain. Like the earth must have been when it was raw and molten-new.

This morning I am watching a pair of golden eagles gliding low over the mountain into a strong headwind. Then they turn, so the wind is behind them, and drift away across the tops. Not once do I see them flap their wings. Wind-dwellers, they are at home inside the wind, can fly into a headwind as easily as they can fly out of it. There are accounts of eagles holding themselves motionless in wind so ferocious that men could not stand upright and slabs of turf were ripped from the rock and flung hundreds of yards.

I climbed after them. I wanted to try and follow this pair, to be up at the same height as the eagles, to be amongst them in their world, meet them as they skirted low across the ridges. For hours I walked along the tops of the mountains, red deer coughing their alarm barks at me. I sheltered from the wind in shallow caves amongst the boulder fields, sipping from my thermos, waiting for the eagles, daydreaming about finding MacGillivray’s unknown species of eagle, his ghost eagle, undiscovered for centuries, the coelacanth of these Hebridean mountains. Spend long enough looking for eagles and you could be forgiven for being haunted by them. Sometimes I have gazed and gazed at a dark shape against the rock convinced it is an eagle, summoning that shape into a bird. Gordon once watched a pair of golden eagles fly into a passing cloud and followed their dim outlines through the depths of white vapour as though, he wrote, they were phantom eagles, or the shadows of eagles.

From one of my shelters I see the male golden eagle again, briefly, gliding back along the ridge towards me. Then he turns and shoots out over the deep glen with its black loch full of rushing clouds and now the reflection of an eagle rushing through those clouds.

Sometimes the hunt begins at a great height. Prey is picked out over a kilometre away – a rabbit cropping the machair, black grouse sparring at the morning lek. Wings are drawn back and the eagle leans into a low-angled glide. At the last moment, wings open, tail fans and talons thrust forward. Stand under the path of an eagle stooping like this and the sound of the wind rushing through its wings is like a sheet being ripped in two.

Golden eagles can also take birds such as grouse on the wing, pursuing the grouse in a tail chase. But eagles need a head start, they need to build up a substantial head of speed, coming out of a stoop for instance, to be successful in overtaking and seizing such a fast bird as the red grouse. Eagles often hunt in pairs, contouring low over the ground together and sometimes even pursuing prey together on the wing. They also, occasionally, hunt on foot, poking about for frogs, young rabbits hiding in the undergrowth.

More often, an eagle hunts only a few feet above the ground, patrolling the same airspace as the hen harrier and short-eared owl. Several times I have watched golden eagles (and once a pair of eagles) hunting like this, glancing over the land, hugging the contours, looking to trip over prey unawares. Stealth is a critical factor in the golden eagle’s ability to catch prey. The bird’s traditional upland prey across its northern European range, grouse and hares, are equipped with supreme agility and speed, and more often than not this speed enables them to escape a golden eagle. It’s a wonder such a large bird could catch anything by surprise … But when you watch an eagle hunting low across the hills it is hard to keep track of the bird. It blends its dark brown plumage against the hillside and clings to the peaks and troughs of the moor. Glide – pause – drop – strike.

I hang above the deep glen watching the surface of the loch. From my perch on the mountain I can see the wind moving across the water. Blocks of colour, like leviathans grazing inside the loch, shunt into each other, black into grey into blue. The surface ripples as if rain were fretting it. Then, two new shadows pass across the water: both eagles are now hanging over the glen and – I hear it first – a raven is beating out from the cliff to harry them.

I am used to the size of ravens. Besides buzzards they are by far the largest bird I see around my home. I often hear the raven’s loud guttural croak as I hang the washing out, and I was glad to hear that call again up here in the mountains. But I had not expected the raven to be so shrunk beside the eagles. This great black bulk of bird I was so used to seeing and hearing, dominating the skies over my home, was utterly dwarfed, reduced to a speck of a bird, buzzing irritably around the eagle pair. I noticed how hard the raven had to work to keep up with the eagles. Either eagle could step away from the raven simply by folding its wings slightly and easing out of earshot of the raven who flapped and croaked, scolding after them. When the eagles pulled their wings back behind them like this, they grew falcon-like in their shape, tidying those great wings away, a split-second change of gear from soar to gliding speed. One of the eagles mock-swooped at the raven, suddenly rushing at it, effortlessly catching and overtaking the raven and then, at the last moment, glancing away.

No bird is so modest in its speed. There is not the impression of speed with golden eagles as there is with the more obvious sky-sprinters, the hobbies and merlins, who appear to live their lives through speed, though Gordon thought that the golden eagle was the fastest bird that flies, utilising its weight in a long glide to gain tremendous acceleration. Gordon once watched a male eagle descend to the eyrie from the high tops carrying a ptarmigan in one foot. The eagle was travelling so fast in its descent that it overshot the nest, rushing past it, before it swung round and was carried back up to the nest by its impetus. Gordon wrote that the speed of that eagle’s dive was quite breathtaking and he calculated that the bird must have been travelling at around 2 miles a minute. An aeroplane pilot flying down the east coast of Greece recorded being overtaken by a golden eagle while the aircraft was travelling at 70 knots. As the eagle passed the plane at a distance of 80 feet the bird turned its head to glance at the aircraft before it eased past it at a speed, the pilot estimated, of 90 mph.

But usually it is difficult to gauge an eagle’s speed and it is easy to think, because of its great size, that it is a heavy, laboured flier. Not until you see it glide over a wide glen in a single gulp or overtake a covey of ptarmigan flinging themselves down through a smoking corrie do you have a sense of what speeds a golden eagle is capable of achieving.

I watched the eagle pair and the raven skirmishing above the loch for fifteen minutes. The raven threaded between the eagles, barking at them, but it seemed half-hearted in its efforts to drive the larger birds off its patch, and there was almost a harmony in this dance, in the interaction between eagle and raven. The eagles seemed unconcerned by the raven jostling amongst them. Sometimes the eagles stole away from the raven and entered their own whirling dance, gliding towards each other and then a last-minute rush of speed as they sheared past, wingtips almost touching. Each time the eagles rushed at each other like this I was sure they were bound to collide, before the last-minute wing adjustment and the pair glanced past each other through the tightening air.

MacGillivray is awake, unable to sleep, running through the inventory of himself. Tomorrow he is planning another visit to the mountains on the border of Lewis and Harris, where he will be amongst friends, where his days will be overseen by eagles, where his unknown species of eagle shimmers on the edge of things. He sits up all night preparing for the trip. He was only in the mountains a few weeks ago but he wants to return to write – to finish writing – a poem. It has been nagging at him all winter, this poem. And he needs to go back to the mountains to get the details of the scenery right. The sense that he has too little material from his first trip to write the thing has been mithering him for months. But more than the poem this trip to the mountains is really about him trying to settle himself, to find a sense of resolution. He writes in his journal:

The chief cause of all my disquietude is the want of resolution …

He needs to calm himself with purpose:

At present I cannot help looking upon the vicissitudes of life with a kind of terror … If I had resolution, I should not despair …

And when he despairs his anxiety boils over and he turns his frustration mercilessly on himself:

… such is the fickleness of my mind, that my whole life, hitherto has been nothing else than a confused mass of error and repentance, amendment and relapse … I am truly ashamed of myself, not to say anything worse …

But before he can begin his walk there is this long unquiet night ahead and all he can do is check the inventory of himself once more, rehearse his daily rituals, as if he were checking the contents of his knapsack:

– Rise with or before the sun.

– Walk at least five miles.

– Give at least half a dozen puts to a heavy stone.

– Make six leaps.

– Drink milk twice a day.

– Wash face, ears, teeth and feet.

– Preserve seven specimens of natural history (whether in propria persona or by drawing).

– Read the chapter on Anatomy in the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

– Read the Book of Job.

– Abstain from cursing and swearing.

– Above all procrastination is to be shunned.

Then it is dawn and MacGillivray is leaving for the mountains. He wants to reach Luachair, the tiny settlement at the head of Loch Rèasort where his friends live, before nightfall. But it is not the best of starts: he misjudges the tides and the great sands at Luskentyre are covered when he reaches them. Shortly afterwards, he loses his way in the mist and rain halfway up the ben.

North, then west, then north again, tacking up through the island. Tarbert to Aird Asaig, through the glen above Bun Abhainn Eadarra, up to the head of Loch Langavat. Lately the island does not recognise itself. People tipped out of their homes, the hills planted with sheep. And the villages all along the west coast of Harris, the machair lands at Nisabost, Scarista, Seilebost and Borve, all of them waiting to follow suit. Dismantling their homes, taking the roof beams with them to the new lives set aside for them on the island’s east coast, a land so pitted with rock not even beasts could live there. Blackface sheep leaking out into the abandoned hills and glens, and so many of them now that, in the moment it takes to turn your back, it sometimes looks as if snow has crept back after the hills have thawed.

One night, descending the hill of Roneval, MacGillivray is spooked by a strange fire flickering on the hillside. He creeps to within a hundred yards of it but then holds back, skirting around the flames through the dark, convinced that the fire had been kindled by sheep stealers, rustling the sheep partly out of anger, partly to alleviate their hunger. Dear Sirs, we are squatting under revolting conditions in hovels situated on other men’s crofts … One hovel = two rooms = twenty-five people crammed to the rotten rafters in there. The people’s situation beggars all description, the poverty just unimaginable; the shores scraped bare of shellfish, nettles, brambles … uprooted and eaten, scurvy seen the first time in a century.

At the head of Loch Langavat, struggling through snow and snowmelt, MacGillivray turns north-west for Loch Rèasort. He has not eaten anything since he set out in the morning dark from Northton. Each bog, each bank of snow, seems to swell before him. But once he clears the watershed between Rapaire and Stulabhal, it is a long downhill glide to Luachair. There! He can see the thin glimmer of Loch Rèasort, the mountains are shutting down its light. Two hours after dark he reaches the house of his friends, opens the door, calls out a greeting to them.

Now I am looking down into the glen with its loch shaped like a rat. If I could bend down from this height and pick the loch up by its long river-tail it would squirm and wriggle beneath my grip. I’d heard of golden eagles doing that to adders, lifting the snakes and carrying them off in their talons as the snakes writhed and contorted in the air like a thread unravelling there. And more exotic things than snakes are sometimes taken by eagles. The lists of prey recorded are eclectic: grasshopper (Finland), pike (Scotland), tortoise (Persia), red-shafted flicker (USA), dog (Scotland, Estonia, Norway, Japan, USA), goshawk (Canada), porcupine (USA) … More hazardous, perhaps, than even a porcupine was the stoat that an eagle near Cape Wrath was once seen to lift, the eagle rising higher and higher in a strange manner then suddenly falling to the ground as if it had been shot. The stoat had managed to twist its way up to reach the eagle’s neck, where it fastened its teeth and killed the bird. Or the wildcat that an eagle was seen to lift in West Inverness-shire: the cat was dropped from several hundred feet and the eagle later found partly disembowelled with severe injuries to its leg.

The golden eagle is capable of predating a wide spectrum of birds, mammals and reptiles, and yet where possible they are essentially a specialist predator, feeding on a narrow range of prey items common to the eagle’s mountain and moorland habitat. Golden eagles adapt to become a more generalist predator when their usual prey is scarce. In the Eastern Highlands of Scotland 90 per cent of golden eagle prey is made up of lagomorphs (mostly mountain hare, but also rabbits) and grouse (both ptarmigan and red grouse). In the Outer Hebrides their diet is more varied because their usual moorland prey, hares and grouse, are scarce here. So, in the Western Isles, rabbits, fulmars and, in winter, sheep carrion make up a high percentage of the eagle’s diet. Grouse and hares are also less common in the Northern and Western Highlands than they are in the east, and consequently the eagle’s diet in these regions is also varied, with deer carrion becoming important in winter. But as a general rule, carrion, despite its availability, tends to be much less significant in the eagle’s diet through the bird’s nesting season, when live prey are preferred, and tend to be easier to transport to the nest than bulky carrion items.

I settle down above the glen with my back against a boulder and keep watch. I can spend hours like this, waiting in the margins for the chance of birds. But today it is a long wait and I can feel the wind drying out my lips. I am just about to give up and move on when I see two golden eagles flying low down a steep flank of the mountain. Their great wings pulled back behind them, their carpal joints jutting forward almost level with the birds’ heads. They cling so close to the side of the mountain they could be abseiling down the incline. An adult bird and a juvenile, the immature eagle with conspicuous white patches on the underside of its wings. All the time the young bird is calling to its parent, a low, excited cheek cheek cheek, the sound carrying down into the glen, skimming across the loch.

Both birds are only 100 feet now from where I am sitting. Through my binoculars I can see the lighter-coloured feathers down the adult’s nape and the yellow in its talons. The juvenile’s calling is growing more persistent, rising in pitch. Then the adult eagle drops fast into the heather with its talons stretched in front of it. At once the youngster is down beside its parent. Something has been killed there. The adult eagle rises and starts to climb above the glen. The young bird proceeds to dip and raise its head into the heather, wrenching at something. I stay with it, watching the young eagle feed. When it has finished it remains in the heather, carefully preening its left wing. Each time the young eagle lifts its wing there is a flash of white in the plumage like an intermittent signal from the grey backdrop of the mountain.

I realise I have witnessed something special, a juvenile golden eagle learning to hunt. The immature bird was clearly still reliant on its parents for food, but it was now piggybacking, tagging along while its parent hunted down the mountainside. The young bird flew so close to the adult, it must have seen the prey in the heather – whatever it was – at the same time as the adult eagle.

I remain watching the juvenile for the next twenty minutes and twice it lifts off the side of the mountain and lands again. Each time it lands it thrusts its talons hard out before it at the last minute as if practising its strike. The adult bird comes back into view again and the young eagle shoots up to meet it, circling its parent, crying repeatedly with its begging call, ttch-yup-yup, tee-yup. I have a very close view of the adult eagle as it swoops low across the cliff in front of me. Its tail is a dark grey colour, like the gneiss beneath it.

It all comes to a head, this gutting of the island from the inside out, when MacGillivray and his uncle are summoned by the laird to decide the fate of his uncle’s farm at Northton. The laird’s factor, Donald Stewart, is there, whom MacGillivray does not care for, whom he calls a wretch of a man. Donald Stewart, who is as ruthless as the sea, who will clear the bulk of the people from the west coast of Harris by 1830, who will even plough the graveyard at Seilebost till skulls and thigh bones roll about the ground like stones. And now Stewart has his eye on the farm at Northton, which is the finest farm in the country. So MacGillivray’s uncle has been duly summoned to the big house at Rodel for this meeting – the Set, as it’s known – and MacGillivray goes along to support him, to steady him, just as his uncle steadied MacGillivray when he was learning to shoot a gun all those years ago. The pair of them enter the house at Rodel where Stewart and the laird, MacLeod, are holding court at a large table, and before MacGillivray and his uncle have even sat down they are told that his uncle has lost the farm, that it has already been decided and would he like to bid for a different farm instead? What happens next is truly wonderful: MacGillivray’s uncle, distraught and silent, listens, Stewart seethes and listens and MacLeod squirms and listens and gulps at his snuff, while MacGillivray stands up and harangues them, boiling over with indignation at the injustice, at Stewart’s duplicity, at MacLeod’s promises to him about the farm. MacGillivray is like the sea that night in January when the wind picked up the water in whirlwinds of agitation. He is furious with MacLeod and Stewart, but most of all he is furious with Stewart, who he knows is really behind all this, the wretch. And when he has finished fuming at them, MacGillivray sits down and there is a long silence. Stewart sits in cowardly silence and MacLeod, who is also a coward, gulps prodigiously at his snuff. Then MacLeod nods and it’s settled and the farm is his uncle’s for another year at least. The rent is set at £170, the meeting is over and MacGillivray and his uncle are both leaving and making straight for the nearest public house.

Seton Gordon once helped a golden eagle cross back over from death. He found the eagle hanging off a cliff in upper Glen Feshie. The bird’s foot had been almost severed by the jaws of a trap which was fixed to the top of the cliff. Gordon and a companion quickly haul the eagle up the rock. They are shocked by how light the bird is, how many days it must have been hanging off the cliff. They carry the eagle, so weak it does not struggle, to some level ground. Very reluctantly, Gordon amputates the leg at the break. They wait and then watch the eagle as it starts to flop its way along the ground towards the precipice. Gordon’s friend shouts at him to catch the bird before it is dashed to its death, but he is too late and the eagle has reached the edge of the cliff. It wavers there and they are sure it is going to fall to its death. But then the eagle tastes the icy uprushing current of wind, opens its broad wings, and rises.

The story of birds of prey in these islands is the story of the birds’ relationship with humans. The nature of that relationship is integral to understanding the history and the current status of raptors in the British Isles. The status of golden eagles in the Outer Hebrides today is linked to the events that precipitated the meeting between MacGillivray, his uncle and the laird that day in April 1818. In particular, the eagles’ current status is linked to the work of the factor, Donald Stewart, who wanted to evict MacGillivray’s uncle and who went on after that meeting to clear the people from the west of Harris in the 1820s and 1830s to make way for his sheep. For the legacy of those clearances – the way those events have impacted the landscape of these islands – is still felt by the eagles today. The sheep that replaced the people brought, through poor husbandry, a ready supply of carrion to the hills, enabling golden eagles to live at high densities in these mountains. At the same time the intensive grazing pressure the hills were put under by the flocks (and more recently the large red deer population) produced, eventually, a degraded landscape, stripped of heather, of nutritional quality, and in turn denuded of its native herbivores, grouse and hares in particular. There have been dramatic declines across the region of grouse and hares, the golden eagle’s natural prey. And whilst golden eagles can live at high densities in these mountains, they do not breed as well here. Live prey – its nutritional value – is critical to the breeding success of golden eagles; the birds breed better where live prey still thrives, as it does, for example, in the Eastern Highlands. The legacy of those clearances from MacGillivray’s time is still felt, their impact on the land has been as dramatic as the ice.

I miss so much compared with them. Gordon, for instance, on the side of Braeriach, finding the perfect impression of a golden eagle’s wings, like the imprint of a fossil, in the freshly fallen snow. MacGillivray: noticing how the currents in a channel are lit by different shades of brightness from the moon. Gordon: watching the aerial display of a male golden eagle, noticing that his neck seemed thinner than the female’s and that the male’s wings appeared larger in proportion to the body. MacGillivray: noticing the component parts of a raven’s nest: heather, willow twigs, the roots of sea bent and lady’s bedstraw … MacGillivray: not noticing that the eagle he shot and slung over his back fitted him like a cowl, clung to him, its spirit clung on to him.