Читать книгу Raptor: A Journey Through Birds - James Lockhart Macdonald - Страница 12

ОглавлениеIV

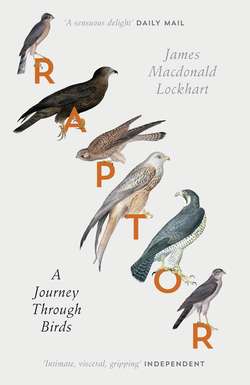

Osprey

Moray Firth

Travelling north, early spring: the osprey’s trajectory. March wakes a restlessness in the birds. Ospreys begin to part their winter quarters, leaving their roosts in the mangrove swamps of West Africa. Staggered departures, a slow release of birds. One morning rising higher than usual on the thermals above the palm-fringed coast, turning north instead of west in a mêlée of mobbing gulls.

What does that restlessness feel like in the bird, that longing to leave? It must be overwhelming. The muscles needing to work, tense for work. The pull of the north, the prospect of all that light, dragging at the bird like a rip tide. A thickening of need in the birds to be gone. The journey – the awful journey – thousands of miles across the Sahara, the Bay of Biscay, is not the point. It is getting back to spar and mate and claim a patch. Back to the deceiving north, still shuffling spring with winter.

The first ospreys make land off the south coast of England towards the end of March. Coming in over Poole Harbour, perhaps, up towards Rutland Water. The land below is lit by seams of water. Over the Lancashire Plain there is snow in the plough furrows and the crease of tractor prints, lighting the fields’ veins like a sonogram. Crossing the Southern Uplands, past Tinto Hill, over the Clyde and the cold flanks above Arrochar. Reaching Loch Linnhe, the bird swings north-east and tracks along the watery motorway of the Great Glen. Between Loch Oich and Loch Ness the earth curves just enough for the osprey – the fish-hawk – to catch its first glimpse of the Moray Firth and the huge expanse of Culbin forest, the sea-black wood.

I am reading all I can about ospreys. Of all the dismal stories: the perceived threat to fishponds, the blanket intolerance … The whole of England, Ireland and Wales rid of ospreys. Gone from England by the middle of the nineteenth century (though mostly by the end of the eighteenth). In the north of England the last known breeding attempts came at the end of the eighteenth century at Whinfield Park in Westmorland and the crags above Ullswater. A pair bred on Lundy in 1838 and on the north coast of Devon in 1842. The last known English nest site was at Monksilver in Somerset in 1847. By the beginning of the twentieth century there were only a handful of eyries dwindling in the Highlands. Lochs named after the osprey (Loch an Iasgair: the loch of the fisher) now outnumbered the birds themselves. And the osprey’s rarity hurrying its demise: egg collectors hunting down the beautiful, valuable eggs. A last-minute rally to try to halt the inevitable: barbed wire is draped beneath the remaining eyrie trees, one nest is even given police protection. But the thieves stop at nothing: a man swims across a freezing loch at night, six inches of snow on the ground, clambering up the island’s slippery castle ramparts to reach the nest, swimming back across the loch holding the eggs above the water, his accomplice hauling him in with a rope. Coming out of the black loch like that, his arms held above his head, he looks like a narwhal rising through a blowhole in the ice.

Two years earlier, May 1848, in north-west Sutherland, the egg collector Charles St John waits by the shore of Loch an Laig Aird while his companions go to fetch a boat. There is an osprey’s nest on an islet in the loch and St John can just make out the white head of the female sitting on her eggs. He will write later that he is sorry for what he does next. Before the boat arrives, before they row out to rob the nest, the osprey rises and flies across the loch towards St John. When she comes into range he raises his shotgun and fires. Her wings are so long that when she tumbles to the ground it looks like a windmill has come unhinged and its blades are spinning, falling towards him. She falls slowly like an ash tree’s rotating keys.

Late one May I headed north into the Highlands through a day of immense heat. Water-borne, water-navigating, following the course of the rivers, the Spey and then the Findhorn, travelling deep into osprey country. Rounding the Cairngorms, snow like a ferrule on the caps of the mountains.

I parked on the edge of Culbin forest and began to walk through the trees. Skin prickling with heat. Bronze-coloured pine seeds, like drops of resin, sticking to the sweat on my arms as if a vambrace was growing there. The forest quiet, sleeping off the day’s heat. Wood ants turning over the dead pine needles. Cowberry plants beneath the trees, glossy leaves, bright amongst the granite-dark pines. Slender, silvery rowans like waymarks in the pine-gloom. The forest floor rippling, moving under the ant-pannage.

Ninety years ago Culbin was a restless desert, a vast area of shifting sands. A place so unlike anywhere else in Britain that at the end of the nineteenth century it became home to a population of Pallas’s sand grouse, a species usually found in the deserts of central Asia. Culbin was known as ‘Britain’s Desert’, large enough to lodge in the imagination, a place where history shuffled with mythology: skeletons excavated by the shifting sands were either travellers who had lost their way in its expanse or an ancient race who had lived and foraged along the shingle ridges.