Читать книгу Raptor: A Journey Through Birds - James Lockhart Macdonald - Страница 9

Merlin

ОглавлениеThe Flow Country

A man is walking south from Aberdeen to London. The night before he leaves his home in Aberdeen he dreams of birds, row upon row of birds perched in their glass cases in a locked museum. He walks along the museum’s deserted corridors, his footsteps scurry ahead of him. He wants to slow the dream, to pause and study every specimen. When he looks at a bird he looks inside it, thinks about the mechanics of it, how it works, the map of its soul. But the sterility of the place makes him itchy and the dream begins to tumble into itself as it rushes towards its closing. The birds wake inside their cabinets and start to tap the glass with their beaks. The noise of their tapping: it is almost as if the birds are applauding him. Then some of the cabinets are cracking and the birds are prising, squeezing through the cracks. A mallard drake cuts itself on a shard of glass and he sees its blood beading black against the duck’s emerald green. Then birds are pouring past him and the museum’s roof is a dark cloud of birds. And he – William MacGillivray – is flickering awake.

It is 4 a.m., a September morning in 1819. William MacGillivray is twenty-three, fizzing, fidgety within himself. He writes: I have no peace of mind. He means: he is impatient of his own impatience. Often he is cramped by melancholy. In his journals he checks, frequently, the inventory of himself; always there are things missing and the gaps in his learning gnaw and grate. Travelling calms him, it gives him buoyancy, space to scrutinise his mind. And so he walks everywhere, thinks nothing of a journey of 100 miles on foot through the mountains. He recommends liniment of soap mixed with whisky to harden the soles of restless feet. His own feet are hard as gneiss, they never blister.

He is not unlike a merlin in the way he boils with energy. He once watched a merlin pursuing a lark relentlessly over every twist and turn. The pair flashed so close to him he could clearly see the male merlin’s grey-blue dorsal plumage. The tiny falcon rushed after the lark, following it through farm steadings, between corn-stacks, amongst the garden trees.

He lives his own life much like this, restless, obstinate, plunging headlong after everything. Not unlike a merlin, too, in the patterns of his wanderings, seasonal migrations. Leaving his home on the Isle of Harris to walk – at the beginning and end of every term – back and forth to university in Aberdeen, sleeping under brooms of heather, in caves above Loch Maree. Most of what he knows about the natural world – in botany, geology, ornithology – he has learnt from these walks. He can name all the plants that grow along the southern shore of Loch Ness. Often his walks digress into curiosity. He will follow a river to its source high in the mountains just to see what plants are growing there. Other times he eats up the distance, 40–50 miles in a day. If he stops moving for too long it’s not that his mind begins to stiffen, rather that it trembles uncontrollably.

And now this long walk to London. Because: his mind is a wave of aftershocks and he is desperate – has been desperate for weeks – to be away from Aberdeen, to be out there on the cusp of things. In his house in the city he is tidying away his breakfast, crumbs from a barley cake have caught on his lip. Then a final check through the contents of his knapsack. He calls his knapsack this machine. It is made of thick oiled cloth and cost him six shillings and sixpence. Inside the machine: two travelling maps, one of Scotland, one of England; a small portfolio with a parcel of paper for drying plants; a few sheets of clean paper, stitched; a bottle of ink; four quills; the Compendium Flora Britannica … He picks up the knapsack; its cloth is stiff with newness, like a frozen bat. For a while he tries to knead the stiffness out of the straps. His hands smell like a saddler’s.

Five a.m. Outside in the street the light is like smoke, pale the way his dream was lit. He thinks about the dream, the brightness of the egrets in the grey rooms of the museum. Which way is it to London? It doesn’t really matter, he has no intention of taking the direct route. London is 500 miles as the crow flies from Aberdeen, but before he has even crossed the border into England he will already have wandered this distance, following his curiosity wherever it leads him. There are things he needs to see along the way, plants and birds to catalogue, places he has never been. Also, he is reluctant to leave the mountains too soon. He knows that once he descends out of them, on the long haul to London, the mountains will wrench at him terribly. So he pulls his long blue coat over his back and starts walking into the deep mountains to the west of Aberdeen. Already he feels his mind thawing; in his journal he writes, I am at length free. By the time he staggers into London, six weeks and 838 miles later, the blue of his coat will be weathered with grey like the plumage of the merlin that brushed past him in pursuit of the lark that day.

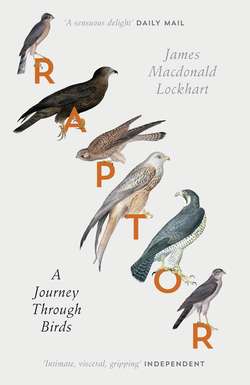

There are fifteen breeding diurnal birds of prey found in the British Isles. This list does not include boreal migrants – bearing news from the Arctic – like the rough-legged buzzard and gyrfalcon, or rare vagrants such as the red-footed falcon, who occasionally brush the shores of these islands. Neither does it include owls. For they are raptors too; that is, a bird possessing acute vision, capable of killing its prey with sharp, curved talons and tearing it with a hooked beak, from the Latin rapere, to seize or take by force. But owls belong to a separate group, the Strigiformes. And although the change of shift between the diurnal and nocturnal birds of prey is not always clear-cut (as I experienced with short-eared owls on Orkney), owls require a list of their own; they are such a fascinating, culturally rich species, they need to be attended to in their own right.

Acute vision is a distinguishing characteristic of raptors. Just how acute is illustrated by this vivid description of a golden eagle recorded by Seton Gordon in The Golden Eagle: King of Birds:

Four days later I had an example of the marvellous eyesight of the golden eagle. The male bird was approaching at a height of at least 1,500 feet. Above a gradual hill slope where grew tussocky grass, whitened by the frosts and snow of winter, he suddenly checked his flight and fell headlong. A couple of minutes later he rose with a small object grasped in one foot. It was, I am almost sure, a field-mouse or vole. Since he had caught his prey at an elevation well above that of the eyrie, he was able to go into a glide when he took wing and made for home. When he had grasped his prey he had torn from the ground some of the long grass in which his small quarry had been hiding: during his subsequent glide, as he moved faster and faster, the grass streamed out rigidly behind him.

Avian eyes are huge in relation to body size, and this is especially the case in birds of prey; many raptors have eyes that are as large, often larger, than an adult human’s. The foveal area in the retina of birds of prey is densely packed with photoreceptor cells. A human eye contains around 200,000 of these cells; the eye of a common buzzard, by comparison, has roughly one million of these rod-and-cone photoreceptors, enabling the buzzard to see the world in much greater detail than we can. Images are also magnified in a raptor’s eye by around 30 per cent. The birds’ eyes are designed much like a pair of binoculars: as light hits the fovea pit in the retina, its rays are bent – refracted – and magnified onto the retina so that the image is enhanced substantially. Birds of prey see the whole twitching world in infinite, immaculate detail.

All fifteen of the diurnal birds of prey breed in these islands, though some in very small numbers. Many are permanent residents. The osprey, hobby, Montagu’s harrier and honey buzzard are summer visitors. All are classified within a single order, the Accipitriformes, and subdivided into three suborders. Accipitridae: the soarers and gliders, the nest builders, distinguished by their broad ‘fingered’ wings; so: hawks, buzzards, eagles, kites and harriers. Pandionidae: with its solitary member, the osprey – a specialist – the hoverer-above-water, the feet-first-diver after fish. Falconidae: the speed merchants (whose nests are scrapes or squats): kestrel, merlin, hobby, peregrine; fast, agile fliers with pointed wings, capable (though not all of them do) of catching their prey in the air.

Pandionidae

Osprey

Accipitridae

Honey Buzzard

Red Kite

Sea Eagle

Marsh Harrier

Hen Harrier

Montagu’s Harrier

Goshawk

Sparrowhawk

Buzzard

Golden Eagle

Falconidae

Kestrel

Merlin

Hobby

Peregrine Falcon

Fifteen birds of prey, fifteen different landscapes. A journey in search of raptors, a journey through the birds and into their worlds. That is how I envisaged it. The aim simply to go in search of the birds, to look for each of them in a different place. To spend some time in the habitats of these birds of prey, hoping to encounter the birds, hoping to watch them. Beginning in the far north, in Orkney, and winding my way down to a river in Devon. A long journey south, clambering down this tall, spiny island, which is as vast and wondrous to me as any galaxy.

Rain over the Pentland Firth. The cliffs of Hoy streaked with rain. The red sandstone a faint glow inside the fret. The low cloud makes the cliffs seem huge, there is no end to them. We could be sailing past a great red planet swirling in a storm of its own making. I am on the early morning crossing from Stromness to Scrabster. Light spilling from slot machines; the bar opening up; breakfast in the ferry’s empty café. Through the window: an arctic tern, so beautifully agile, it seemed to be threading its way through the rain’s interstices. Then a couple from Holland come in, hesitate when they hear themselves in the café’s emptiness. They have been walking for a week through Orkney and their faces are red with wind-burn. They hunch over their breakfasts and I see how we do this too: mantle our food, like a hawk, glower out from over it. We are passing The Old Man of Hoy and all three of us shift across to the port side for a better view. We see the great stack in pieces, its midriff showing through a tear in the cloud. Then the rain thickens like a shoal and The Old Man, the cliffs of Hoy, dissolve in rain.

The way I’d pictured it, back home, doodling over maps, Orkney would be all hen harriers. Then the ferry, the train from Thurso, a request stop and stepping off the deserted platform into the blanket bog of the Flow Country. Then the vast, impossible search for merlins. I knew the birds were out there somewhere, not in large numbers, but I had seen a merlin once before, a skimming-stone, hunting fast and low far out on The Flows, the peaks of Morven, Maiden Pap and Scaraben on the southern horizon, a patch of snow on Morven’s north face like the white dab on a coot’s forehead.

All of that happened as best it could. On the crossing over from Orkney I thought of home – ached for it – for my family there, and thought of the fishermen out of Wick and Scrabster who, should they dream of home, hauled in their nets and headed back to harbour, not willing to tamper with a dream like that. I shared a taxi with the Dutch couple from Scrabster into Thurso. They were tired and polite and wanted to pay, Orkney’s wind still rushing in them. They sat in the back of the cab, their faces glowing like rust.

Waiting for the train at Thurso, a slow drizzle, the rails a curve of light, glinting like mica in the wet. The last stop, as far north as you can go. Buffers, then a wall and then another wall because, if you did not stop, the train would slip like a birthing ship down through Thurso’s steep streets, past her shops and houses and out into the frantic tides of the firth, rousing wreckers from their sleep who go down to poke about the shore like foraging badgers.

Then the warmth of the train, people steaming in their wet clothes. The start of my long journey south. All the staging posts between the moors of Orkney and the moors of Devon lying in wait for me. Reading the maps of each place obsessively, thinking the maps into life, imagining their landscape, their weather. The more I read the maps the more I imagined the possibility of raptors there. That hanging wood marked like a tide line above the valley: perfect for red kites. That cliff on the mountain’s south face: surely there must be peregrines there … The train now pulling away from the north coast. A last glimpse of Orkney shimmering behind us in her veil of rain. Her harriers grounded, hunched under the dripping sky, feathers beaded with rain. The mark I’d made in the heather beginning to fade. Time on the train to reproof my boots, because the place I’m heading for, the next stop on my journey south, hints in its name that I should really be donning waders, flippers, a bog snorkel …

‘Flow’, from the Norse flói, a marshy place. The Flow Country, or The Flows as it is usually known, is the name given to the area of West Caithness and East Sutherland covered by blanket bog (literally bog ‘blanketed’ by peat). It is one of the largest, most intact areas of peat bog in the world, extending to over 4,000 km². Flick the noun into a verb and you also have what the landscape wants to do. The Flows want to flow, to move. The land here is fluid, it quakes when you press yourself upon it. The Flows is the most sensitive, alert landscape I know. A human cannot move across it without marking – without hurting – the bog. The mire feels every footprint and stores your heavy spoor across its surface. But it is a wonder you can move across it at all. There are more solids found in milk than there are in the equivalent volume of peat. The bog is held in place only by a skin of vegetation (the acrotelm), predominantly sphagnum, which prevents the water-saturated lower layer of peat (the catotelm) from starting to flow. And, oh, how it wants to flow! Think of the bog as a great quivering mound of water held together like a jelly by its skin of vegetation and by the remarkably fibrous nature of the peat. Think of that great mound breathing like a sleeping whale. For that is what it does. The German word is Mooratmung (mire-breathing). It is the process by which the bog swells and contracts through wet and dry periods. The bog must breathe to stop itself from flowing away.

As it breathes the bog changes its appearance. Unlike a mineral soil where the shape of the land is determined by physical processes, the patterns and shapes of the bog are continually shifting; peat accumulates and erodes, the bog swells and recedes. Occasionally, after exceptionally heavy rain, the water in the bog swells to such a volume that the peat, despite its great strength, can no longer hold the mound together. So the bog bursts, hacking a great chunk of itself away. In Lancashire in the mid-sixteenth century the large raised bog of Chat Moss burst and spilt out over the surrounding countryside, taking lives and causing terrible damage, a great smear of black water blotting out the land. Huge chunks of peat which were carried down the river Glazebrook were later found washed up on the Isle of Man and as far as the Irish coast.

The train follows the river Thurso. Herons in their pterodactyl shadows. The river so black it could be a fracture in the earth’s crust, an opening into the depths of the planet. Passing Norse farmsteads, Houstry, Halkirk, Tormsdale. The Norse language here flowing down from Orkney and spreading up the course of the river. Flagstone dykes marking field boundaries. Sheep, bright as stars against the pine-dark grass, disturbed by the train, cantering away like brushed snow. Then the train is crossing an unmarked border, a linguistic watershed, the last Norse outpost before the Gaelic hinterland of the bog, a ruined farmstead with a Norse name, Tormsdale, peered down on by low hills, each one attended to by its Gaelic, Bad á Cheò, Beinn Chàiteag, Cnoc Bad na Caorach. The last stop, as far as the Norse settlers would go. Because if you didn’t stop here you would wander for days adrift on the bog before you sank, exhausted, into the marshy flói.

‘Bog bursts’, ‘quaking ground’, ‘sink holes’ … I am trying to pay heed to the dramatic vernacular of the bog, checking my boots are well proofed, my gaiters are a good fit. I must remember to check and recheck compass bearings against the map, must remember to tread carefully over this landscape. Because once, I nearly lost my brother in a peat bog.

Another family holiday, another peaty, midge-infested destination. This time, the Ardnamurchan peninsula, Scotland’s gangplank, the jump off to America. My brother was six or thereabouts and we had been to the village shop, where he had bought a toy car. More than a car, it was a six-wheeled, off-road thing. Orange plastic like a street lamp’s sodium glare, round white stickers for headlights, a purple siren on the roof. My brother took it everywhere. And lucky for all of us he had the car with him on a walk up the hill one afternoon, holding the toy out in front of him, chatting to it, running through some imagined commentary, when he dropped, as if down a hole, into what looked like nothing more than just a puddle. The bog had got him. And he was struggling, sinking into the mire. But his instinct was to protect the car, to stop it getting muddy. So he held it out in front of him and by holding his arms out like that he stopped himself sinking any further and we leant over and hauled him out, oozing with black peat, like some urchin fallen down a chimney.

The train glides across the flow. Fences beside the track to hold the drifting snow. Tundra accents: greylag, skua, greenshank, golden plover. Wild cat and otter’s braided tracks. Sphagnum’s crimson greens. Red deer, nomads in a great wet desert, stepping between the myriad lochans. Mark the deer, for they can blend into the backdrop of the flow as a hare in ermine folds itself against the snow.

Then the train is pulling into Forsinard, where the Norse language has flanked around the bog and found an opening to the south through the long, fertile reach of Strath Halladale. And halfway down the strath met and fused with Gaelic making something beautiful. Forsinard: ‘the waterfall on the height’. Fors from the Norse (waterfall); an from the Gaelic (of the); aird from the Gaelic (height). Clothes still dank with Orkney rain, smelling of rain, I stepped down off the train, crossed the single-track road, and walked out into the bog in search of merlins.

What else does he have in his knapsack, his machine? He has taken it off while he pauses to rest at Banchory, 23 miles out of Aberdeen. He leaves the road, sheds his coat and washes his hands and feet in the river Dee. He notices how people’s accent here has slipped away from Aberdeen, a softening in the tone, a slower pace to it, as if the dialect here still carries a memory of Gaelic. And sure enough, a little further up the road he passes two men on horseback talking in Gaelic. He speaks Gaelic himself, has considerable knowledge of Scots and its many dialects. All along his journey he passes through the ebb and flow of dialect. Every mile along the road accents are shaved a fraction. Often he struggles to make himself understood. He might follow a seam of Gaelic like a thin trail through the landscape until it peters out on the outskirts of a town.

What else is in his knapsack? Two black lead pencils; eight camel-hair pencils with stalks; an Indian rubber; a shirt; a false neck; two pairs of short stockings; a soap box; two razors; a sharpening stone; a lancet; a pair of scissors; some thread; needles. In a small pocket in the inner side of his flannel undervest there is nine pounds sterling in bank notes. One pound in silver is secured in a purse of chamois leather kept in a pocket of his trousers. In all, ten pounds to last him through to London.

That first day he walks as far as Aboyne, 30 miles from Aberdeen. That night, at the inn, he writes in his journal until the candle has burnt down. He writes a long list of all the plants he has seen that day, both those in and out of flower. He dreams again of the museum, the place obsesses his dreams. But this dreaming is inevitable because the museum is the reason he is making this walk to London. He has heard that the British Museum holds an astonishing collection of beasts and birds, of all the creatures that have been found upon the face of the earth. And he must go to London to see these things. There are gaps in his knowledge, in the survey of himself, he needs to fill. As a student at Aberdeen he studied medicine for nearly five years, then, in 1817, switched to zoology. Since then he has devoted himself completely to studying the natural world. Linnaeus and Pennant have been his guides but now he has reached the point where he needs to set what he has learnt of the natural world against the museum’s collection. He wants to check his own observations and theories against the museum’s. Above all, he wants to see the museum’s collection of British birds. Birds are what stir him more than anything. He is anxious to get there, to get on with his life.

The way I’d pictured it, back home planning this journey, was a neat transition: Orkney’s hen harriers followed by merlins out on The Flows. Instead, on Orkney, merlins had darted through my days, led me astray across the moor in search of them. Then, not far out of Forsinard, in a large expanse of forestry, the first bird I saw was a male hen harrier, a shard of light, hunting the canopy.

Before I set out on this journey I had planned to try to look for each species of raptor in a different place, to dedicate a bird to a particular landscape, or rather the landscape to the bird, to immerse myself as much as I could in each bird’s habitat. But the plan unravelled soon after I lay down in the heather on Orkney and a jack merlin, a plunging meteor, dropped from the sky, wings folded back behind him, diving straight at a kestrel who had drifted over the merlin’s territory. It was astonishing to see the size difference between the birds, the merlin a speck, a frantic satellite, buzzing around the kestrel. He was furious, screaming at the kestrel, diving repeatedly at the larger bird until the kestrel relented and let the wind slice it away down the valley.

I stayed with that jack merlin for much of the day. Sometimes I would catch a flash of him circling the horizon or zipping low across the hillside, full tilt, breakneck speed. The sense of sprung energy in this tiny bird of prey was extraordinary, a fizzing atom, bombarding the sky.

Once I tracked the merlin down into a dusty peat hollow below clouds of heather. I marked the spot and started to walk slowly down the moor towards him. Grandmother’s footsteps: every few paces I froze and watched him through my binoculars. At each pause the colours of his slate-blue back grew sharper. Even at rest he was a quivering ball of energy, primed to spring up and fling himself out and up. Relentless, fearless, missile of the moor, you would not be able to shake him off once he had latched on to you. There are stories of merlins – like William MacGillivray’s account of watching a merlin pursuing a lark amongst farm steadings and corn-stacks – where the falcon is so locked in on the pursuit of a wheatear, skylark, stonechat, finch or pipit (the merlin’s most common prey species) it follows them into buildings, garages, in and out of people’s homes. Even a ship out in the Atlantic, 500 miles west of Cape Wrath, became, for a week, a merlin’s hunting ground. The crew reported that the merlin – on migration from Iceland – hitched a ride with them, chasing small migrant birds all over the ship, darting across the gunwale, around coiled hillocks of rope, perching on the bright orange fenders.

They don’t always get away with it, this all-out pursuit; merlins have been known to kill themselves, colliding with walls, fences, trees. Merlins need the space – the sort of space there is on The Flows – to run their prey down. They do not possess the sparrowhawk’s agility to hunt through the tight landscape of a wood.

I am still playing grandmother’s footsteps with the merlin, but I do not get very far before one of the short-eared owls overtakes me and swoops low over the merlin, disturbing him, dusting him, so that he flicks away out of the peat hollow and lands again further down the slope. I mark his position. This time he has landed on a fence post. There is a burn running down towards the fence and I drop into it and use its depth to stalk closer to the merlin. I crawl quietly down the burn and, when I poke my head up again over the bank, the merlin is still there and I am very close to him. He is looking up at the sky, agitated. His breast is a russet-bracken colour, his back a blue-grey lead. That’s it: he is gone. The female is above us, calling to him, a sharp, pierced whistle. And then I see the merlin pair together. She is a darker shape, a fraction larger. In his description of the merlin, William MacGillivray picks out the distinction between the male and female’s dorsal colouring brilliantly. The male’s upper parts he describes as a deep greyish-blue; the female’s as a dark bluish-grey. But now I cannot make out any difference between the pair. Both the male and female merlin are gaining height, moving away from my hideout in the burn, pushing themselves into speed.

They were beautiful distractions, those Orkney merlins, pulling me after them, away from the hen harriers I was supposed to be watching. And throughout my journey, at every juncture, different species of raptor, inevitably, moved through the places I was in. So, hen harriers spilt out of Orkney and, like the Norse language, followed me across the Pentland Firth; merlins flickered through many of the moorland landscapes I visited; buzzards were present almost everywhere I went, however much I tried to convince myself they might be something else, the something that was eluding me – goshawk, honey buzzard, golden eagle … Every buzzard I saw made me look at it more carefully.

Quickly the map I had imagined for my journey became a muddled thing, transgressed by other birds of prey, criss-crossed by their wanderings. And though each staging post was supposed to concentrate on a single species, I loved it when I was visited, unexpectedly, by other birds of prey. I liked the sense that the different stops along my journey started to feel linked up by the birds, I liked the ways they set my journey echoing. Sometimes I came across a bird of prey again far from where I had first encountered it: a merlin on its winter wanderings in the south of England, an osprey on the cusp of autumn refuelling on an estuary that cut into Scotland’s narrow girth.

The great Orkney ornithologist Eddie Balfour discussed, in one of his many papers on hen harriers, the minimum distance harriers nest from each other (hen harriers, notably on Orkney, will often nest in loose communities). But in a lovely afterthought to this, like a harrier pirouetting and changing tack, he touches on the optimum distance between nests as well, the distance beyond which breeding stimuli would diminish, neighbourly contact become lost. Extending the thought outwards from hen harriers living in a moorland community, he imagines larger raptors, golden eagles, with their vast, isolated territories, living, in fact, like the harriers, within a single community that extended across the whole of the Highlands, each nest within reach of its neighbour, like a great network of signal beacons.

I was fascinated by this idea of a community of raptors extending right across the country. It touched on my experience of re-encountering and being revisited by birds of prey as I journeyed south. Balfour’s idea also seemed to challenge the notion that many birds of prey were solitary, non-communal predators, inviting the idea that even a species we perceive as being fiercely independent, like the eagle, still belongs to – perhaps needs – a wider community of eagles. It got hold of me, this idea, it got hold of the initial map I had sketched for my journey and redesigned it. Instead of moving from one isolated area of study to the next, from Orkney to the Flow Country and so on, I started to see myself passing through neighbourhoods – through communities – of raptors, the boundaries of my map – the national, topographic, linguistic borders – giving way to the birds’ network of interconnecting, overlapping territories. A journey through birds.

The first bird I see as I am walking through the forestry above Forsinard: a male hen harrier, hunting the sea of conifers. And I could still be on that hillside in Orkney, except, what has changed? The bird, the bedrock, remain the same, but the sky is different here, not always rushing away from you as it is on Orkney. The wind is not as skittish here, the vastness of the land seems to stabilise it, give it traction. On Orkney I wonder if the wind even notices the land. And what else has changed, of course, are the trees that no more belong out here on the bog than they do on Orkney, where trees don’t stand a chance against that feral wind. But still there are conifers here planted in their millions, squeezing the breath out of the bog. And today the male harrier is hunting over the tops of the trees just as I watched the Orkney harriers quartering the open moor. It is the same procedure except here, over the forestry, he is looking for passerine birds to scoop out of the trees. It is fascinating to watch the harrier hunt like this, as if the canopy were simply the ground vegetation raised up by 20 feet.

To begin with the newly planted forests would have been harrier havens, just the sort of scrubby, ungrazed zones they like to hunt, ripe with voles. But all of that is gone once the trees thicken and the canopy closes over, suffocating the bog. Greenshank, dunlin, golden plover, hen harrier, merlin, birds of the open bog, are forced to move on, or cling on, as this harrier was doing, trying to adapt to his changed world. Recently, hen harriers – always assumed to be strictly ground-nesting birds – have been observed nesting in conifer trees where the plantations have swamped their moorland breeding grounds. Hopeless, inexperienced nest builders, little wonder their nests are often dismantled by a febrile wind.

But this harrier I am watching over the forest still has its nest on the ground. From my perch on the hillside I draw a sketch of his movements over the trees. Meandering, methodical, he covers every inch of the canopy. I watch him drift above the trees like this for half an hour until (I recognise it from Orkney) there is a sudden shift in purpose to his flight. He stalls low above a forest ride, hesitates a fraction, then whacks the ground with his feet. I make a note of the time: 14.50: he lifts from the kill and beats a heavy flight direct across the tops of the trees; there is the female harrier rising towards him; 14.51: the food pass; 14.52: the female keeps on rising, loops around the male; 14.53: she goes down into a newly planted corner of the forest. The trees are only a few feet tall here and I mark the position of her nest: four fence posts to the right of the corner post, then 12 feet down from the fence.

The hen harrier is the bird that brought me to William MacGillivray. The moment came when I was meandering, harrier-like, through books and papers, field notes and anecdotes about hen harriers. Then I read this passage from MacGillivray’s 1836 book, Descriptions of the Rapacious Birds of Great Britain:

Should we, on a fine summer’s day, betake us to the outfields bordering an extensive moor, on the sides of the Pentland, Ochill, or the Peebles hills, we might chance to see the harrier, although hawks have been so much persecuted that one may sometimes travel a whole day without meeting so much as a kestrel. But we are now wandering through thickets of furze and broom, where the blue milkwort, the purple pinguicula, the yellow violet, the spotted orchis, and all the other plants that render the desert so delightful to the strolling botanist, peep forth in modest beauty from their beds of green moss. The golden plover, stationed on the little knoll, on which he has just alighted, gives out his shrill note of anxiety, for he has come, not to welcome us to his retreats, but if possible to prevent us from approaching them, or at least to decoy us from his brood; the lapwing, on broad and dusky wing, hovers and plunges over head, chiding us with its querulous cry; the whinchat flits from bush to bush, warbles its little song from the top-spray, or sallies forth to seize a heedless fly whizzing joyously along in the bright sunshine. As we cross the sedgy bog, the snipe starts with loud scream from among our feet, while on the opposite bank the gor cock raises his scarlet-fringed head above the heath, and cackles his loud note of anger or alarm, as his mate crouches amid the brown herbage.

But see, a pair of searchers not less observant than ourselves have appeared over the slope of the bare hill. They wheel in narrow curves at the height of a few yards; round and round they fly, their eyes no doubt keenly bent on the ground beneath. One of them, the pale blue bird, is now stationary, hovering on almost motionless wing; down he shoots like a stone; he has clutched his prey, a young lapwing perhaps, and off he flies with it to a bit of smooth ground, where he will devour it in haste. Meanwhile his companion, who is larger, and of a brown colour, continues her search; she moves along with gentle flappings, sails for a short space, and judging the place over which she has arrived not unlikely to yield something that may satisfy her craving appetite, she flies slowly over it, now contracting her circles, now extending them, and now for a few moments hovering as if fixed in the air. At length, finding nothing, she shoots away and hies to another field; but she has not proceeded far when she spies a frog by the edge of a small pool, and, instantly descending, thrusts her sharp talons through its sides. It is soon devoured, and in the mean time the male comes up. Again they fly off together; and were you to watch their progress, you would see them traverse a large space of ground, wheeling, gliding, and flapping, in the same manner, until at length, having obtained a supply of savoury food for their young, they would fly off with it.

Attentive, accurate, warm and intimate, you cannot help but feel MacGillivray’s delight at being out there amongst the birds. The degree of observation: the way he records the hen harrier’s flight, the detail in the landscape, the description of the moorland flowers and moorland birds. It felt to me like the work of an exceptional field naturalist; the writer seemed to notice everything. And I wanted to read more, had to read more. Felt a kinship there, at least in the way MacGillivray responded to the birds. He caught the hen harrier’s beauty in his careful, graceful writing.

I walk through the middle of the day across the bog. Anything that breaks the horizon draws you towards it. The house is so far out on the flow it is like a boat set adrift. Not long abandoned, the building sagging, tipping into the bog. A portion of the corrugated-iron roof torn back, exposing timber cross-beams. Rock doves blurt out of the attic. Outside the house there is a bathtub turned upside down; four stumpy iron legs sticking upright, like a dead pig. In one of the rooms: a metal bed frame, a mattress patterned with mildew, blue ceramic tiles decorating the fireplace. A dead hind in the doorway, the stench of it everywhere. Deer droppings piled against the walls as if someone had swept them there.

MacGillivray often slept in places like this on his long walk to London. One night, on the outskirts of Lancaster, tired and wet, he stumbled upon a large, misshapen house in the dark. He went inside and groped his way around till he had made a complete circuit of the rooms. There was no loft, not even a culm of straw to bed down in, but earlier he had tried to sleep under a hedge and the house, despite its damp clay floor, was preferable. So he slept behind the door in wet feet with a handkerchief tied around his head, woke to a mild midnight to peep at the moon and walk up and down the floor a bit. Then slept again with his head on his knapsack to wake at dawn and walk down to the river to wash his face.

But that restless night on the outskirts of Lancaster comes much later. It is only five days since MacGillivray set out from Aberdeen and he is still in Aberdeenshire, crossing the Cairngorms on route from Braemar to Kingussie. He spends the night of Sunday 12 September high in the mountains in a palaver of sleeplessness and shivering. Supper is a quarter of a barley cake and a few crumbs of cheese. After which he does his best to make a shelter out of stones and grass and heath, then settles the knapsack and some heather over his feet, to try to keep the cold at bay.

He wakes at sunrise and resumes his climb into the mountains. It is slow going and he pauses often to rest; his muscles, after so little food, shiver with fatigue. At the source of the Dee he pauses to drink a glassful of its cold, blissful water. Up on the plateau he finds moss campion and dwarf willow; in the steep grey corries: dog’s violet, smooth heath bedstraw, alpine lady’s mantle.

During my time in Caithness and Sutherland I heard rumours of merlins. People were generous with their knowledge, pointing places out to me on my map. Somebody’s faint memory of a nest site was enough to set me trekking far out across the bog. One afternoon I walked out to a distant mountain that rose sheer out of the flow. I had been told that a corrie high on the mountain’s north face was a traditional nesting site for merlins. I walked there through a land creased with water, through dense clusters of dubh lochans, the hundreds of small lakes that form beautiful patterns across the surface of the bog. In some places the lochans are packed so tightly you can drift through their mazy streets for hours with no sense of where you might emerge. Most of the pools are shallow, two or three feet deep, though occasionally one would sink its depth into blackness. Water horsetail grew in some of the shallower pools, bell heather and cotton sedge along the banks. Around the edge of the pools were great mounds of sphagnum moss built up like ant hills. I pushed my arm into one of them, losing it up to my shoulder in the moss’s cool dampness, sphagnum tentacles crawling over my skin. Some of these mounds had been perched on by birds, wisps of down feather left behind, the imprint of the bird’s weight on the soft moss.

Hours I spent out there on the bog, and so many distractions on the way to the mountain, so much water to weave around. At one point, I gave up and slithered otter-like between the lochans, swirling up clouds of peat particles when I dived into the pools. And somewhere out on the flow a great boulder – just as the abandoned house had done – drew me towards it. A huge lump of rock, 20 feet high, jettisoned by the retreating ice. There was a solitary mountain ash growing up through a crack in the rock like a ship’s mast. I clambered up the boulder and found, on the slab’s flat top, a plate of bones. I had discovered an eagle’s plucking perch, bones strewn everywhere, on the slab and in the heather around the base of the boulder. Amongst the bones there was a red deer’s hoof, its ankle still clothed in grey hide.

It was mid-afternoon by the time I reached the mountain and climbed up to the corrie. I sat down with my back against a rock, listened and waited for the merlins. A corrie is the mountain’s cupped ear. It is a contained space away from the rushing noise of the tops, an amphitheatre of silence. You walk into it and enter an enclosed stillness where everything is suddenly closer, amplified, the raven’s croaking echo, the golden plover’s whistle. I was glad to be out of the wind. I thought, if merlins were here, their calls would sound cleaner, sharper, and hopefully I could track them more easily by listening out for the birds. But, something about the quiet stillness of the corrie, the release from the rushing wind out on the flow … when I sat down beside the rock, I fell asleep and when I woke the corrie had grown cooler, thicker with shadow.

Later I heard another rumour, a sure bet this time, a place where merlins nested year after year. The site was a deep cut through the flow where a burn wound down towards the river. I walked there across the glittering bog, light finding and lifting pools into pools of light. Near the burn I found signs of merlins everywhere: chalk-marked boulders – perches, lookout posts – patterned white by the birds’ excretions.

There are some neighbourhoods of the moor that draw merlins to them time and again. It is difficult to identify what it is about a location that has so much appeal, but availability of prey and suitable nesting sites play a crucial role in the land’s capacity to draw in raptors. In his pioneering study of merlins in the Yorkshire Dales published in 1921, William Rowan observed nineteen different pairs of merlins return to the same patch of heather every year for nineteen years. Each spring there was always a new influx of birds because each year, without fail, both the male and female merlin were killed by gamekeepers on their breeding ground and their eggs destroyed.

It was enough for keepers to set their traps on top of a merlin’s favourite lookout boulder. No need to even camouflage the trap: the merlin’s fidelity to certain perches always outweighed the bird’s mistrust of the sharp jaws of a trap. Rowan used to plead – even tried to bribe – the keepers to spare the merlins. He had watched grouse quietly foraging bilberry leaves right in front of the adult merlins at their nest, so he knew that merlins posed no threat to grouse. But a few days before the grouse season opened the keeper would go out early with his gun and clear the moor of hawks of every shape and size. And every year another sacrificial pair of merlins arrived to plug the gap. Rowan wondered where they came from, this surplus tap of merlins, replenishing the same patch of moor year after year. What was it about that clump of heather on the side of the fell that had such a pull on the birds? Rowan identified a few characteristics of the place, of merlin nests in general: a bank of deep, old heather; an expansive view from the nest site of the surrounding moorland; a number of lookout boulders above the nest …

But it is hard to see the land as the birds must see it, to feel a place as they must do. I am always looking for clues in the landscape, trying to anticipate the birds from the feel of a place. The ornithologist Ian Newton observed that, when he was studying sparrowhawks in South West Scotland, he could glance inside a wood and tell straight away if its internal landscape was conducive for sparrowhawks. Eventually, after you have spent time amongst the birds, once you have settled into their landscapes, you can walk through a wood or sit above a moorland burn and think: this is a good place to be a hawk, I could be a hawk here.

I keep well back from the burn and settle myself against one of the boulders. The rock is limed with merlin droppings and I think, of all the things that draw a merlin down onto a particular bank of heather, these white-splashed boulders, like runway lights, must guide the birds in, signalling that this is a good place for them, signalling to the birds that generations of merlins have bred here.

Then – my notebook records the time – 10.30: ‘Heard male merlin calling and turned to see him just above me. He gained height and then flew fast, dropping to ground level and skimming out across the bog, a smear of speed …’ I try to keep up with him but he is rushing so low against the ground, eventually the haze and fold of the moor fold him away. I try to pick him up again, but the vast acreage of sky, the speed of the tiny bird … I have lost him.

That was the pattern for much of the day. There were long absences when the merlin was hunting far out on the flow. I caught the occasional flash of him through my binoculars when he glanced above the skyline, followed him as he tumbled downwards and levelled out over a great sweep of the bog. Sometimes I was impatient to follow him out across the flow, to try to intercept him out there. But I knew that would be hopeless, I could never follow a bird so absorbed in its own speed. Gordon would have kept still and waited. Rowan would have kept still; I thought of William Rowan, his night-long vigils in the cramped hide on Barden Moor, buried in tall bracken, so close to the merlins’ nest that, when he lit a cigarette to help ward off the flies that infested his hide, the smoke drifted over the female merlin, parted round her, making slow eddies of itself as the falcon bent to feed her young.

You have so little time to take in what you see of merlins. Their world is glimpsed in snatches of blurred speed. I was lucky on Orkney to have spent time beside a merlin who paused long enough for me to notice the russet plumage of his breast. But the merlin seen rushing past you in a bolt of speed is just as beautiful. At times, from my perch above the burn in the Flow Country, watching the male merlin coming and going, it felt like I was in a meteor storm. Always I heard him calling first, then scrambled to pick him up just in time to glimpse his sharp-angled wings and his low rush up the burn. On one approach, I heard the male call and the female answered him, a high-pitched cheo, cheo, cheo. As she called (still out of sight) I noticed the male suddenly jink mid-flight as if he’d tripped over a rise in the moor. Then it looked as if he had grazed, scraped something – another bird – because there was a small explosion of feathers beneath him. And just at that moment I saw a second bird rising from under him and realised it was the female (who up till then I had not seen) meeting the male there, receiving prey from him.

Later, when the moor was quiet, I walked up to the spot where the merlin pair had met. When the female gathered the prey from the male she must have scuffed it, loosening feathers from the dead bird. There was a dusting of feathers across the site where the food pass had taken place: down feathers snagged in the heather and in the cotton grass. How else could two birds of such charged intensity meet except in an explosion, a fit of sparks? I picked up some of the loose feathers and lined my pockets with them. Then I walked on up the burn, following in the merlin’s slipstream.