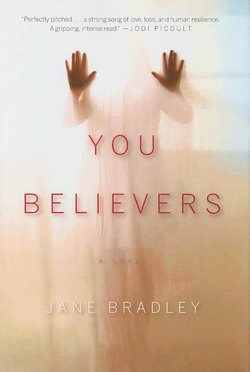

Читать книгу You Believers - Jane Bradley - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Love Calls Us to Things of This World

ОглавлениеBilly woke in the dark, a jolt in the spine and a wide-eyed stare at the ceiling. Day three and she wasn’t back yet. He sat up, looked at the clock: 3:30 A.M. As usual. Somewhere between 3:30 and 4:30, he would wake. She was always home by then, even when she worked late at the bar, partied with the wait staff. He stared into the dark. Not a sound in the house. Most nights he’d hear the clicking of ice as she brought her glass of ice water to bed. When she worked late, she always came in quietly, took a shower, brushed her teeth, and he never heard a thing but the clicking of her ice water as she set it on the side table, slipped so quiet, soft, and damp into their bed.

Three thirty A.M. What does a man do at 3:30 A.M.? Five thirty is a civil time to rise. That was what Katy said: “Five thirty is a civil time to rise.” Farmers did it. Fishermen. Even those yuppies with some 6:00 spinning class at the gym. She said that getting up before 5:30 meant you were anxious or a nut of some kind or a workaholic. Katy liked sleeping in. In her ideal life, she said she’d like to be able to rise clean and clear-headed with the sun so she could watch the night turn to day. She said that as if she believed it. But Katy never got up early unless she had to. She wanted to be the kind of person who got up early, greeted the day just for the beauty of it, but people did that only in the books she liked to read.

If she were there, she’d reach, stroke his back softly with her nails. She’d pull him to her where he could smell coconut, amber, some sweet-smelling cream she used. He’d nuzzle at her neck while she softly rubbed her fingers across the back of his head. “Come to bed,” she’d whisper, even when he was already there. He’d just nuzzle closer, breathing her sweetness.

He flicked on the light, threw a t-shirt over the lampshade to soften the glare. Katy hated when he did that, said he’d forget the shirt one day and burn the place down. Right now he didn’t care. He looked around the room as if looking would reveal some sign of her, as if all that time he was looking she was right there, the way you looked for a drill bit you needed in a toolbox. You looked and sifted and looked, and you gave up, made some other drill bit work. You went to put it back, and there it was—the drill bit you needed was sitting right there.

He ran his hands over the tangle of sheets. Katy would have had them smooth, tight, and clean. He could see a stain. She hated stains on a sheet, kept saying she wanted new sheets. And so he’d bought these eight-hundred-thread-count sheets she’d wanted. He was saving them for a wedding present. Their first night married, they’d sleep on those ivory-colored eight-hundred-count sheets. “Katy,” he said, “I got you those great sheets you’ve been wanting. Come home.”

The cops had said it was probably prewedding jitters. He was worried she had run back to Frank, the asshole who never remembered her birthday or Valentine’s Day. Frank, who seemed to want her just enough to hurt her. Some guys were like that, and some girls just couldn’t leave it alone. And now there was this other guy called Randy. Who the hell was Randy? Katy’s mother suspected Frank. But even Olivia—he could hear it in her voice—was scared. Olivia didn’t know about some guy named Randy. Billy didn’t want anybody to know about Randy. He’d read about him in the journal, the journal he’d promised not to read. She’d written, “Randy the randy man. Yikes! Ha ha!” What kind of grown woman wrote things like that? No hearts around Randy’s name the way she did with Frank, just little doodles of firecrackers and stars

He glanced at his bedside table, the half-empty bottle of Jim Beam, the bag of pot. Nothing worked. He sat, nerves jangly at 3:35 A.M. If he finished the bottle, took a couple hits of weed, he could sleep again and maybe wake again when it was a civil time to rise. But his mouth was thick and dry as cotton, so he drank the glass of water instead, what should be Katy’s glass of water, and there it was, in case she came in, on his side of the bed.

He grabbed his phone, punched in Frank’s number—of course he remembered Frank’s number. He’d gotten it off her phone when they’d first gotten together. She knew he’d done it. After that the phone stayed locked. It was a sign of guilt that she had to keep her phone locked. She just sighed and shook her head when he asked about Frank. “We’re friends, Billy. Old history. Sometimes old lovers, the chemistry dries out. I’m marrying you, Billy.” She said it like it was the biggest news of the world. Then she’d turn away, say something like “Sometimes old lovers can just be friends.” Yeah, he knew that. But he knew she was lying. He’d seen the heat between them, the kind of heat that never fully went away. And now he had some guy named Randy to worry about too.

He listened as the phone rang a few times, wondered if Frank would bother to answer. Probably not. He’d be with some girl. Maybe Katy. The phone kept ringing. Well, it was 3:45 A.M. Hardly a civil time. It switched to voice mail, blah blah, Frank’s voice, “Leave a message.” He sat in the silence. What could he say at 3:45 A.M.? Frank had to be sick of him calling just to ask, “Is Katy there? Tell me the truth, is she there?”

Then there was a click and the deep, thick voice. Frank, with the kind of voice women liked, dark and smooth. A goddamned white Isaac Hayes. Shaft and you can dig it. The voice said, “Hello,” but Billy could hear it really saying, Yeah, what now?

“It’s me,” Billy said.

“Billy,” Frank said, “I’ve got caller ID.” Billy could hear him sitting up, maybe readjusting the pillows. “She’s not here, Billy. I swear I’ve got no idea where she is.”

“Yeah,” Billy said. “I’m sorry, man. I know you said that. But you’d tell me if she’s there? ’Cause I’m going crazy not knowing. I mean I’ve called her mom. Nobody knows where she is, and I just keep thinking if it’s anybody, it’s you. ’Cause, oh, hell.” He sucked back a breath. “Hell, everybody knew she still loved you. I was just the safe guy. You’re the danger guy, and the girls, they like the danger guy.”

“Billy,” Frank said, calm like a doctor, like his daddy, who had this preacher’s soft way of saying just about everything.

“What?”

“She’s not here, Billy. I haven’t seen her since y’all came back here for the engagement party.”

“Are you alone?” Billy said. There was a pause. “You’re not alone, are you, Frank? Shit, guys like you never sleep alone.”

“I’m gonna hang up in one minute, Billy. I’m just trying to be decent here. I’m trying to help, but I got no idea where she is. Hell, I wish she was here, and I don’t mean for me but for you. I know it’s been three days, and I know this ain’t like Katy.”

“Her mom’s coming,” Billy said. “Her mom’s so worried, she’s coming down.” Billy didn’t know why, but it soothed him just to have her mom come down.

Billy heard Frank saying something, then the mumbling of a girl’s voice in the background. She sounded sleepy. She sounded pissed. It wasn’t Katy. “I’m sorry, man,” Frank said. “It’s just three days. Sometimes girls run off longer than that.”

“Maybe the kind of girls you go out with. Girls I go out with don’t run off. They want to marry me. She wants to marry me.” Billy felt the crying in his voice. He leaned toward the ashtray, picked up the half-smoked joint. Relit it. Held it. Breathed. Billy held the joint away from the phone as if that could hide what he was doing.

“Get some sleep, man,” Frank said. “We’ll all feel better if we can get some sleep.”

“Yeah.” Billy rubbed the joint out, looked at the bottle of Jim Beam.

“Look,” Frank said, “call me if you hear something.”

“Sure,” Billy said. “Sorry, man.” He flicked the phone shut, opened the bottle, but when he went for a swig, a heaving rose in his gut, and he ran to the john to throw up.

He retched and heaved until his whole body was shaking and tears ran down his face. He leaned back against the cold tub, grabbed a towel off the rack, and wrapped it around his shoulders. He pulled the bath mat under him for a little cushion and leaned back against the tub.

He reached up to the sink, ran the water cold, filled a glass, leaned back and sipped. Easy, now, he thought. Small sips. He leaned back, closed his eyes, felt the pounding in his chest ease. Olivia had said it would be all right. Olivia had said that there was an explanation for these things, that her daughter would never run off, but sometimes a girl just needed girl time. Maybe Katy was off with her girlfriends. Olivia didn’t know about some guy called Randy, and Billy couldn’t bring himself to tell her about the name in Katy’s last journal, the one Billy had sworn he’d never read. So let Olivia think Katy was off with girlfriends; let her try to believe that. But Billy had heard the shaking in her voice. She wouldn’t have booked a plane if she thought it was all right. And even if Katy had run off with some guy named Randy, it wasn’t like her not to call and tell him where she was. She’d at least text if she didn’t want to talk on the phone. Unless she’d really left him for good.

Billy walked to the living room, saw the photos of Katy spread on the coffee table. The REV lady had said she’d need a photograph if he wanted her to make a flyer. Billy stood there, afraid to go closer to the photographs. He couldn’t believe this was really happening. The REV lady was coming tomorrow. You didn’t get calls from searchers if everything was all right. He’d seen her on the news. Shelby Waters. She helped cops find bodies, although that wasn’t how she’d put it. “No, I don’t go searching for bodies, Mr. Jenkins. I support people who have lost . . .” She went on, but that was all he heard. People who have lost.

He went back to the bathroom for another glass of water. He looked down at the grime caked at the base of the tub. It was his turn to clean the bathroom. He grabbed a piece of toilet paper, scrubbed at a black spot in the caulk where dust and dirt and moisture made that black mildew not even bleach could get out. He spit on the toilet paper, wiped at the spot. The toilet paper fell apart. He tossed it into the toilet, slammed the lid down, sat up. The cops had asked, “Are you sure nothing’s missing? Toothbrush, birth-control pills, perfume?”

He looked around. She’d left her cell phone. But she was always forgetting her cell phone. And all her favorite things were here. The birth-control case. Her Vitabath soap, the stuff she loved and they couldn’t afford so her mom always got it her for Christmas and her birthday. And there were her other things: Amber Shea Butter, bath salts, her makeup and cleansers and lotions overfilling the two drawers, cluttering the shower. It was no wonder he always put off cleaning the bathroom when he had to go to all that trouble to move her things. She could always tell when he hurried and wiped the rag around whatever was on the shelf, said, “Do it right, Billy.” But it wasn’t like she was perfect. Her truck was a garbage can on wheels. He hated to ride in that truck of her daddy’s, but the truck was one good thing he’d left her, so she kept it running, new engine, transmission, but something was always going wrong. She said she’d drive it into the ground, and she drove it hard, filling the floorboards with Coke cans, beer cans, chip bags, candy wrappers, and rocks and leaves and branches she’d found from walking around the lake. She was always filling the truck bed with driftwood and broken chairs and lamps she’d pull from the garbage on the side of the streets. “We all have our sloppy spots,” she liked to say. “We’re all entitled to our sloppy spots, and Daddy’s truck is mine.” He figured it was hers to do what she wanted with.

At least she liked the house clean, and Billy was grateful for that. No matter how messy his mind felt after a day on the job, when he came home to see the prettiness, the brightness, the clean sheets and shelves she’d brought to his house when they’d made it their house, it was all peace. She took one shabby brick house and made it something wonderful just out of scraps of things she’d find, stitch up, repair, and paint. Only one month after she moved in with him, he asked her to marry him, please. She gave one little blink and looked around as if the answer hovered around her head like a little bugging mosquito she needed to catch. She looked at him as if there were a sudden solution to something she had been puzzling over for years.

“Yes,” she said. “Billy Jenkins, I’ll marry you. I’ll even change my name for you if you want.” But later they’d talked about that. She didn’t see why a woman would give up the name she’d been born and raised with when she married some guy and odds were they’d end up divorced, and then she’d be carrying around some name like gum stuck to her shoe.

He just nodded like he agreed and said okay because there was no use arguing. He just kissed her and asked if she’d mind wearing his grandmother’s ring. And she kissed him and said it would be great. Or maybe he said that, or maybe he just thought that. But anyway, she was wearing it. He hoped she was wearing it. Wherever she was.

He looked around the bathroom that she’d wallpapered with sentimental-looking little blue cornflowers on a white pattern, girly but not too girly, a clean little print, so fine and crisp you had to look close to know it was a cornflower. She’d pointed that out—he hadn’t even known what a cornflower was. She’d been so proud of hanging that wallpaper, he hadn’t bothered to point out the places where the design didn’t line up. There’d be a row of half flowers jutting up against white space where the row of other half flowers was supposed to be. But that was all right. It was Katy. She always meant to get things perfect, and that was one of the things he loved about her, but sometimes he thought he loved her more because she didn’t get things perfect. It was the trying to get perfect, a sweetness in the trying, that he really liked.

And there on the racks were what she liked to call her “delicates”—had to be a word her mom had taught her, some proper term for panties and bras. She liked good underwear, was always cruising T. J. Maxx for cheap prices. She liked lace, black, white, green. Nothing too trampy, and little thongs, and her little bras that never matched. Now he sat there looking at her delicates, waiting for her hands, her fingers to take them down, fold them, place them in her drawer the way she liked.

She liked everything just so. She’d studied poetry and philosophy and all kinds of stuff in college. And she always had this simple, smart way of talking about things that he liked to hear but didn’t understand. Like the poem she loved: “Love Calls Us to the Things of This World.” It was a line she liked to say. She couldn’t remember who wrote the poem, or much of the rest of the poem. All she remembered about it was something about laundry.

He couldn’t believe some guy had gotten famous for writing something like that. It was kind of obvious to him that if you liked the world, you liked the things in it, but she said it was all more mysterious, or did she say it was more complicated, than that. He didn’t know, but she liked the line so much she wrote it out in calligraphy letters and framed it. All Billy knew was that the poem was about laundry. Billy didn’t get that either, that some guy could get famous for writing about laundry. But here it was: “Love Calls Us to the Things of This World.” And there near the bottom corner of the frame was a little drawing she’d done: his shirt and her blouse on a clothesline. She’d said it was their clothes, and the clothes hanging there were a metaphor. He loved it when she talked like that. He loved all the pretty, useless things she made and put all over his house. Their house. But he couldn’t remember what love had to do with laundry.

“Katy,” he whispered, and felt that little rush of anger like when she came home too late from work. But then he felt that knot in his throat. She wasn’t with Frank. So maybe it was this Randy guy. But she would have called by now. She wasn’t that cruel. He thought maybe he should just take her things down, stick them in her drawer like everything was normal. He started to reach, but he couldn’t touch them. Her things would wait for her hands to put them away. “Please don’t touch her things,” he’d said when he’d seen the cop reaching for them. He was glad he’d said “please” because his voice had snapped, and the cop had flinched a little, had given him a look like One more word out of you and I’ll bust you just for getting in my way.

The cop had taken a box of her hair dye from the bathroom trash, studied it carefully, held it at a distance with his latex-gloved hand. “So she dyed her hair before she left,” he said as he dropped the box into an evidence bag. “She was touching it up,” Billy said. And the cop said, “She wasn’t a natural blond, was she?” Billy walked out of the room because he knew there was pot in the coffee can in the freezer, and he knew the cop was just looking for a reason to put cuffs on him, take him in.

He stood and looked in the mirror. He looked like a drunk. Red eyes, crazy hair, the puffed, sagging jowls of a drunk. No wonder the cop was itching for a bust. He looked like the kind of guy who hung around job sites scoping them out for scrap metal, tools, a cooler with some food in it. He heard the twittering of the predawn birds. Another day was coming, another day she was gone. Another day he’d skip work, just go crazy. He washed his face hard with a rag and soap, hot water, then cold, and more cold. Cold water helped hangover skin. Katy had told him that. But he still looked like a drunk. And it was because he was a drunk. He’d been drinking solidly since the night Katy hadn’t come home. And he wasn’t even really a drinker. Katy was the drinker—not a big drinker but a drinker. He liked pot. Pot worked to smooth the edges out of any long workday. But whiskey did something more. This guy named Gator who hung at the bar where Katy worked, he believed in the power of whiskey, said, “Pot softens things, but whiskey just blots it all out like a total solar eclipse, man. It all gets still and dark. Just don’t look too long straight at it. You go blind, man.” Gator had this way of laughing like there was nothing better in the world than going blind. Billy thought he was nuts, but Katy liked him. Katy felt sorry for him. But Katy was always feeling sorry for things most people didn’t notice. Maybe that was all this Randy person was, some other guy she’d taken in.

He looked back at her drawing, his blue cotton shirt, her pink ruffled blouse, like the kind of blouse she liked to wear on days she was feeling “girly.” The last thing he thought of her was girly. But there they were in the frame: his shirt, her pink blouse, framed like they’d be sharing the bathroom and laundry forever. Then he remembered: “Let there be laundry for the backs of thieves.” The other line from the poem. She’d shout it sometimes: “Let there be laundry for the backs of thieves,” and laugh the way some people did when they hollered, “Merry Christmas.”

He didn’t get it. He’d read the poem. It said “clean linen,” not “laundry,” but he still didn’t get it. And he didn’t correct her when she shouted it out wrong. It made her happy. She had told him the poem was about forgiveness, that to love the world was to forgive it. But he’d never gotten what all that had to do with laundry and thieves.

But he figured it had something to do with the fact that she’d volunteered to do laundry for this homeless guy named Gator. He was a Vietnam vet, and he lived in the marshlands across the river. He made what money he could by working as a river guide for tourists and fishermen. He was a good guy, all tanned and blue eyes, not bad-looking when he smiled. But he was just a little bit crazy in that he preferred living his life out there with the gators and snakes rather than with people. Billy just figured that was what war could do.

And Gator was looking a whole lot better with Katy’s care. She cut his hair once a month, and she did his laundry every week. Brought it home in a trash bag from the bar and took it back all folded and neat in another trash bag, a clean one.

Billy thought maybe Gator had some idea where Katy was. He’d been a scout in the army . . . maybe he knew something. Maybe he could help. After three days of solid drinking and steady smoking, Billy wasn’t blind yet. He could see enough to know he looked like a drunk in the mirror. He could see her panties on the towel rack, the empty wastebasket, the grime around the tub. He took the framed picture off the wall, hugged it to his chest. “Hold on,” he said as he walked to the kitchen. He saw that it was bright with daylight and a wreck of Chinese takeout and uneaten pizza. Flies buzzed all over. “Shit,” he said. “I’m sorry, Katy.” He swatted at flies around the sink and stuck the dishes in the dishwasher. He poured the powder, slammed the door closed, and jammed the button to click the machine on. He opened the back door, used a newspaper to swat flies out. Then he dug under the sink for the last trash bag. That was on Katy’s list. She was going to pick up trash bags at the Rite Aid when she got her prescription. There were other things they needed that she’d been supposed to pick up that day. He stood gripping the sink, enjoying the steady vibration of the dishwasher. As long as he gripped that countertop, he was pretty certain he wouldn’t fall to the floor and be a puddle of hungover mess when that REV lady showed up. He remembered she was coming tomorrow. But tomorrow was today.

“Shit,” he said, and he pitched beer cans, containers, and boxes into the bag. They had company coming, and Katy would want it clean. He sprayed air freshener all around the kitchen. “It will be fine, Katy,” he said, talking to the framed words of the poem. He grabbed a broom. “We’ve just got to go through the motions of looking for you. It’s like that drill bit I thought I lost one time. I was looking and looking, and when I reached in my pocket for some quarters, I found it. It was right there next to me the whole time. I’m gonna look and look for you. And then I’m gonna turn and see you are right here. Where you belong. With me.”