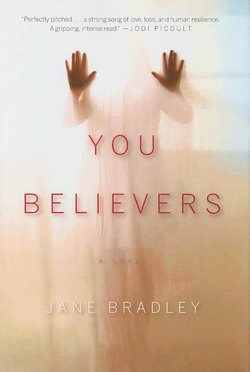

Читать книгу You Believers - Jane Bradley - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Bodies

ОглавлениеWhen Wilmington police searched for Katy Connor, they found a woman’s leg, fish-belly white, gray at the crease at the back of the knee, black at the top where someone had hacked it off before tossing the leg into the stream. A blue Keds sneaker still clung to the foot in spite of the suck and pull of so much water. It wasn’t Katy’s leg but some other woman’s leg, another woman’s story we will never know. This is Katy’s story. At least I think it’s Katy’s story. It’s hard to say sometimes where one woman’s story ends and another begins.

It’s classic, almost. Like the story of Persephone picking flowers in a field one spring afternoon. The earth opens. Hades comes roaring up in his chariot, black horses digging up dirt with their hooves, hot breath swirling from flared nostrils. With a quick swoop of thick, muscled arm, Hades snatches the girl, drags her down to the underworld. You know the story. A mother comes to the rescue, finds her daughter has eaten six seeds of the dark fruit, pomegranate seeds that crunched between the girl’s teeth, red juice running from her lips.

And the mother’s world, the whole wide world, is changed.

You could say it could be anyone’s story. People go missing every day. That twelve-year-old blond who disappears while waiting for her school bus one spring morning. The woman last seen turning away from an ATM camera. Sometimes we find them. Sometimes not. Most often we find remains.

My name’s Shelby Waters, and you don’t know me, and you might not ever want to know me because I’m a searcher. I’m the one you call when someone you love goes missing. Yes, of course you call the cops first, and you should. But once the cop is gone with his report and the profile of what went down rising up in his mind, and you’ve got nothing left but worry and waiting for the phone to ring, you call me.

And I listen to your sorrows and fears and speculations. And you, like everyone who’s missing someone, hope for the best and fear the worst. That’s a hard line to walk. So I step in and I look at your pictures, letters, whatever fragments you might have that belong or relate to the one you’ve lost. I try to fill in the gaps between what you think might have happened, what you fear might have happened, and what did go down and how it went. And while I’m figuring the story, I’m doing my best to make you feel you can stand and walk, and no matter what happens, you can go on and live.

It was my sister, Darly, got me started on this.

I was always the hard, shy one, but Darly, she was the popular girl. You know the kind, with blue eyes and a sweet little mouth that makes you think of cherries. All the boys liked her. The girls too. She was the kind anyone could love. Pretty and sweet, you know, not taken with her own beauty, just cheerful and helpful and good. She grew up, got married, and moved out of our little cove called Suck Creek to Chattanooga. Momma had a bad feeling, but mommas most often have bad feelings about their babies moving away. But the rest of us, well, we were proud. I mean Suck Creek isn’t exactly the kind of place where people do big things in life. In the old days it was pretty much moonshiners and poor folks making do with some kind of labor. Some say there was a curse on the place for all the shooting and drinking and general meanness that went on back in the woods off the roads. Some say it was cursed by the Cherokee when they got pushed out on that old Trail of Tears.

There was a creek there, Suck Creek, looked clean and deep and just right for swimming in the summer. It sat back a little from the Tennessee River, where the rainwater runs off the mountain, just tucked back a little in the cove. It looked calm enough, but now and then there’d be this current, some said it was the pull of the river way down beneath, but something would shift, pull people under. And they’d drown. Mostly kids and drunk teenaged boys. My momma liked to say God looks after drunks and little children, but living in Suck Creek, I don’t know how she could hold to that way of thinking. But she was strong on religion. Lots of folks are strong on religion back there. Momma said one day they had a revival out by that creek, and there was a woman there. Lillian Young was her name. My momma knew her, said she had some power of God working in her. She’d once stopped two boys from lynching this black boy just for riding his bike back in there. The white boy that brought him in, the redneck boys knocked his teeth out. They beat the black boy pretty bad. His face was all bashed in. They were throwing a rope over a tree limb. Had the noose tied. Some of the boys tried to keep Miss Young away, but she pushed on, saying, “I want to know what you boys are doing back there.” And when she saw what they were doing, she stopped it all right, just by calling those boys down with words. She said, “God is not pleased with what you boys are doing.” And they listened. They all knew Miss Young. She’d go all around there helping the old folks, teaching the young ones to read. So those boys, they quit their beating on that black boy, and she yanked him up, shoved him toward his bike, and said, “In the name of Jesus, get on that bike, get home, and never, ever, come back here.” Whenever she said something in the name of Jesus, something changed in the world. Everybody believed in the powers of Lillian Young.

So after that revival, when folks were all full of faith and joy in salvation, Lillian Young decided it was time to go out and pray over that creek, pray for whatever evil lay beneath that water to vanish, in the name of Jesus, of course. She prayed, “Lord, if this creek gives you no glory, in the name of Jesus, take this creek away.” They say she said that a few times, along with some others praying. And it wasn’t a week later a big storm rolled through, tore up the riverbank, changed the way the rain flowed down the mountain and into the river, and that creek, it disappeared. I do not lie about this. That creek was gone. And Miss Young, well, she came to be known from Knoxville to Tuscaloosa for the holy woman she was.

I wish we had her now. And I wish we had had her to pray over Darly before she moved away. Like I said, Momma had a bad feeling, and to tell the truth I did too. I thought maybe I was worrying about being lonely for my sister, so I told Darly I was proud she was moving off and going to college to be a nurse. It wasn’t long before she had a job and a husband and a house and all that stuff a woman’s supposed to get in this world. And it was good for a while. Then, on her way to work one morning, Darly disappeared.

You never believe it at first. You go looking for the simplest explanation, the thing you want to believe, like she just met up with a friend and forgot to call. But they found her white nurse’s cap on the shelf in a phone booth, her little white MG broken down by the side of the road. No signs of a struggle, just a car, keys hanging in the ignition. The car had had some kind of engine trouble. It was always getting her stuck on the side of the road. She’d probably be alive today if she’d done like my daddy always said to and bought a Dodge.

I had a dream the morning she disappeared. I was planting red tulips in black dirt, and Darly rode by the house in a black car. She was in the passenger seat in the dream. I didn’t see the driver. She just looked at me, so sad. I straightened up from digging in the dirt and said, “Darly doesn’t like this.” I woke up with those words. And I wondered why I was dreaming about Darly. I mean I’d seen her around, but we’d kind of drifted apart with me still back in Suck Creek running the Quick Stop and her off being a nurse and married and all. While I was pouring my coffee that morning, my momma called, told me about the phone booth, the car, the keys still there. I knew it was bad.

After the cops investigated her husband and did a half-assed job of a search, they gave up looking. Too many other crimes to get on to, they said, or something like that. I knew we’d find her in time, not Darly, but what was left. It’s a hard thing to learn to live with what’s left when so much is always falling away. A year later two hunters out for deer found Darly in the brush in the north Georgia mountains where only hunters go.

Police never found the facts, just figured it was some guy saw an easy target. Such a little woman, her nurse’s uniform bright in the predawn darkness. Did he snatch her from the phone booth? Or did he, smiling, offer her a ride? These are the questions that got me started. With answers I’ll always want to know. I tried to talk to Darly all those months she was gone, and I sent up prayers trying to catch a sense of her spirit. But Darly never answered. I guess I’m no Lillian Young because no matter how much I cried out, God just sat silent and shadowed as those deep, dark mountains back there. Once they found her remains, I gave up on God. And I couldn’t look at mountains without thinking what meanness might be going on. I used to love mountains, had no fear of any kind of wildness out there. But I got to where I couldn’t even get off our porch, so my momma thought I should visit my cousin in Wilmington. He ran a bar out on the beach. No mountains, just sea and sky and sand. I needed that. And it was good for a while. All those happy tourists, big beach homes and condos and parties and money and laughter flowing in and out like the tides.

But then this little girl went missing from town, from downtown, where it’s bad. Word was her momma was a crack whore, so the cops, well, you know cops. So I called and met the grandmomma, who was the one really raising that girl, who took her to church, kept her clean, made sure she did her homework. The girl deserved a search. Her name was Keisha. That was the first thing I did, make sure the city knew a nine-year-old girl named Keisha Davis was missing and needed to be found. Given the momma’s way of living, I had a feeling Keisha wasn’t dead; she’d just been stolen for a while. Taken by somebody who’d seen her in her momma’s house, somebody who knew how to snatch a girl without a sound. And I knew with enough word on the street we’d find her. I told every little dealer, thief, and hooker I could get to listen to keep an eye out. Waved a fifty-dollar bill at ’em, then put it back in my pocket. Said, “You get me the word that finds that girl, you’ll get this fifty, and you’ll be my friend. And you never know when you’ll need a friend like me.” Maybe I do have a little Lillian Young in me ’cause I got their attention. But you gotta cover all the odds and work fast when it’s a child lost. So I raised a search crew from her grandmomma’s church. We put up flyers and started asking questions and searching that city, one alley, abandoned home, and Dumpster at a time. Then we stretched the search to the banks of the Cape Fear River, with me thinking if she had gotten in that river, she was gone. Turns out one of the hookers got the word, some guy told her about some girl locked up in a room, said it wasn’t right doing little girls like that. Turns out it was an uncle who had her. I don’t even want to count how many times it’s some uncle doing these things. He had her in a house three blocks away. Another crack house, another uncle, another girl. You know the story. She was alive at least, but she was broken way past where anything could mend. I see a lot of this.

It’s a calling, really, what I do. The way some folks are called to the church. When someone goes missing, people do a lot of praying, and being from Suck Creek, I know a lot about praying and sitting around and more praying when something needs to be done. And, well, that bothers me. All that she’s in God’s hands and comforting talk and a whole lot of it’ll be all rights. There’s lots of times it won’t be all right. It’ll be hell, and my job is to get folks through it.

But don’t get me wrong, I think praying is a good thing. It’s a start. It gives some kind of comfort and a little bit of hope. But like my momma used to say, “You gotta put feet on your prayers if you want something done.” She said that was what Miss Young believed. And any woman who can knock two Suck Creek rednecks back from beating a boy, she’s got strength. When Momma packed me off to live here, she said, “You gotta get your prayers moving across the ground, Shelby Waters. You gotta set your prayers in motion instead of just letting them go floating out there in the air.”

I started my search for Keisha by raising money from the church where she went, then other churches, then just people. In time I started something that would make my momma, daddy, and Lillian Young proud. REV, I call it. Rescue Effort Volunteers. While lots around here are all about saving souls, I’d say my calling is saving lives, lives of the missing and the lives of those who get left behind. I’ve led those gatherings of searchers through fields, armed with guns, sticks, shovels, any kind of protection against the snakes that wait in weeds, the alligators lurking in marshes, where somewhere in miles of fields and woods and rivers and lakes a body can be found.

I always know when we’ll find them. My eyes tear up like from a chemical burn, my stomach heaves, and my head gets all thick and swimmy, like my whole body is saying it doesn’t want to see. But I push on through the bad feelings, keep walking, keep using my stick to push back the weeds. And then: remains, skin matted with leaves baked by the sun to the bones, ribs riddled with spiders, beetles, centipedes. And there’s the shirt sometimes clinging, a watch, a ring, a shoe.

I step in between the police reports and camera crews when a family discovers a loved one is lost. I see what most don’t, the story behind statistics and the news. I’ve seen the mother vomiting in a hotel room in the city where her daughter was last seen alive. I’ve seen the father who cried because he lost a flashlight while looking for the body of his son at the county dump. He was a big man, collapsed on a pile of cinder block. He sobbed the words, “I just had it in my hands. I just had it.” I found his flashlight, gave him a bottle of cold water to soothe him a little. Kept moving on.

I’m trying to tell you the story, but to give you the story would be like giving you the churning blue sea one bucket at a time. You might taste the salt, feel the cold, but the weight and wave of so much water, well, it’s lost.

Like Katy.

Like the woman who once walked on that leg hacked off and tossed to rot in a stream.

Bodies.

Joggers find them in the bushes by well-traveled roads.

Bodies are tossed in ditches, woods, and fields. Some are left in Dumpsters in back alleys. Some are dropped in rivers and lakes, like fish caught, thrown back, not worth keeping. Floaters, they call them, when bodies fill with gases and rise to the surface of the dark water that consumed them. Something inside stirs, expands, causes them to rise.

A parent always knows whether the child is just missing or is truly gone. And I can read it in the lines of their faces, the shadows, those sad, sad shadows in their eyes. But when I met Katy’s momma, I wasn’t so sure. I could see the sorrow of a child gone, but I could also see the life that comes with love, living love, hanging on. Which is another story. She’s from Suck Creek too. You gotta pay attention when you run to the end of the earth to get away from Suck Creek and a little piece of Suck Creek comes drifting up, swirling around your feet. I mean that was the feeling I had when I met Olivia Baines. I kind of recognized the accent and got to asking questions. And when she said she was from Suck Creek, I got this swimmy feeling, like it was pulling me back. So of course I felt the calling, said I’d do everything in my power to find her girl.

I picked the picture for Katy’s flyer, went through all those photos her fiancé had, picked the one of her smiling with this big, happy, tennis-pro kind of smile, thick dark hair unfurling in a breeze. She was looking at her fiancé, who held the camera. She was looking like a woman who had no idea just how beautiful she was. She was looking like a woman in love. And it took me back to my sister, Darly, who had that same kind of smile and wavy long hair. I wanted the whole town to fall in love with Katy Connor, to work to find her. Strangers gathered weekly for the search. Church groups, bikers, even some of the homeless climbed on the bus to help.

Katy Connor thought she was safe. She was supposed to be safe at three o’clock in the afternoon in the parking lot of a strip mall on one of the busiest streets in town. She did nothing wrong. She bought a bag of clothes and walked to her truck.

It can happen like that.

You think you’re going home. And some picture of your face ends up on a grainy black-and-white flyer tacked to a phone pole. Your image fades in sunlight. The thin paper sign of you tatters, fluttering in the breeze. Strangers pass by, study your face for something familiar, think maybe they’ve seen you somewhere. But they haven’t. You are a stranger. You are lost.

Loved ones can find themselves composing you on a MISSING sign like this:

MISSING

from Wilmington, North Carolina:

Katherine (Katy) Connor.

5’10”, 130 lbs.

Blue eyes. Long brown hair.

Tattoo of a cross on her shoulder.

Last seen on June 22 at the Dollar Daze

store in Briarfield Plaza. Her blue Chevy truck

with Tennessee plates found 50 miles west of

Wilmington in Columbus County.

If you have any information, please . . .

Long ago they tattooed members of nomadic tribes to identify the body in case of death; the missing could be returned to the family for proper burial, to put the soul to rest. The system often worked, depending on time and the ways of weather.

Today they use a more reliable system of dental records.

But people will always go missing and prayers unanswered. Lost souls go wandering. We all know this, and bodies are calling to be found.

You could say this is a ghost story in some way. A crime story. A classic kind of tale. Biblical almost, but not quite.

Katy didn’t know that day would be a story. Katy didn’t know Jesse Hollowfield was watching for his chance. She didn’t know that at any moment the continental plates miles underground can shift, the earth crack apart, an unseen hand reach, grip, throttle the street, sending it all tilting as someone gasps, someone screams, maybe, if there’s time to comprehend the darkness reaching up, maybe to yank a whole world down. No one is ready for it when something snaps, eclipses the sweet blue world. And no one stays the same after a thing like that.

It can happen, I tell you. Like this: