Читать книгу You Believers - Jane Bradley - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

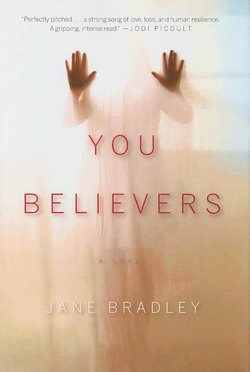

You Believers

ОглавлениеJesse Hollowfield and Mike Carter knew which cars had automatic locks. They sat waiting just behind the strip mall, patient as lions hunkered in the reeds, heads raised to sniff the humid air while watching gazelles herd, looking for the weak, the young, the one alone. The Datsun’s engine was running because when they shut it off, half the time the engine wouldn’t fire again, and it was hell to roll-start a car in the North Carolina flatlands when the sun can break your back with the heat.

Katy didn’t see them—she had a things-to-do list in her purse: gas station, the library to drop off books, the drug store to pick up birth-control pills. She had left a note for her fiancé on the refrigerator door: “Be back when I can.” But driving by the strip mall, she saw the Dollar Daze sign and got the impulse to buy something new for her trip back home. She pulled into the side lot, where the sun wasn’t directly bearing down.

Jesse gave a nod. “Check it out. That chick parked between the Dumpster and the ATM. That truck, what year is that thing? Looks old, but listen to that engine.”

Mike watched the truck. The girl was bobbing her head a little, like she was singing. Mike leaned a little out his window, heard the sounds of a Bob Marley song coming from her truck. She had to be happy listening to that song. He said, “Maybe we don’t want an old truck. We need a good truck.”

Jesse shoved Mike’s shoulder. “Listen to that engine. It’s tuned. Somebody takes care of that thing.” He nodded, whispered, “She’ll ride all right.”

Katy sat in the truck, moving to the beat. Bob Marley’s music always made her think of beaches and beer.

“Come on,” Jesse whispered. “Get out of the fucking truck.”

Katy turned off the engine and stepped out into the sun.

Careless, Jesse thought as she dropped the keys into her unzipped purse, dangling loosely from her arm. He leaned forward, his back straight, jaw tight, eyes fixed on the woman with nothing on her mind but where she thought she was going to go. He guessed her weight: 125-130. Tall but skinny. He’d take her truck and anything she had in that piece-of-shit fake-leather shoulder bag.

Katy walked toward the store, hoping to find something cute in the racks of five-dollar tops and twenty-dollar jeans. She didn’t have much cash, and her card was maxed out. But she wanted to look good for her trip. She wanted her mom to know she was doing something more than tending bar these days. She’d tell her she was learning how to hang wallpaper; she was practically an interior decorator. Her mother would want to talk about wedding plans. She would want to look at Katy’s hand, touch the engagement ring as if she needed to see it was still there, proof that yes, Katy was finally settling down.

Katy stopped, stood still in the heat. She’d be married in a month. To Billy. She was leaving the one she still wanted, Frank, behind. But she didn’t want to settle. And there was the new guy, Randy—Randy, who made her laugh; Randy, who’d get her high for free anytime she wanted. Randy had told her, “Sure, you go on and get married, but you and me both know you’ll never really settle down. You’ll always come running to Randy when you get those little bad-girl needs.” No one knew anything about Randy. Billy thought his only problem was Frank back in Chattanooga. He suspected that when she went back home, it was more about seeing Frank than her mom.

“Let me take this one last trip,” she’d told Billy. She would party with old friends at the marina on Lake Chickamauga, the way they always did when she returned home. Frank would be there. “I need one more trip,” she had said. “One more trip back home, alone. I miss my mom.”

Billy had told her she could go, but he had a bad feeling.

“What?” she’d said. “Tell me your feeling; go on and say it.”

Billy had lit a joint, said, “Frank.” He’d looked straight at her. “I can tell when you’re lying, Katy.” Then he’d left her standing in the kitchen while he’d gone on to work with a joint in his hand. Just another fight, she’d told herself. She’d take a drive, let it go. She’d make lasagna for him when she got home. He liked it when she took the time to make a real meal. He called them good-wife meals, and he’d tease her, say he saw past her wild streak, saw the happy, peaceful, good wife she wanted to be. And he was right. Maybe. She hoped he was right.

She stared at the pavement and knew Billy had a right to be jealous. She knew she hurt him, but she just couldn’t resist the need sometimes to break a rule. To be a little bad. It gave her a rush, like leaping off a high dive. “I’m sorry,” she said out loud. She’d told Billy that a hundred times: “I’m sorry” for something; then she’d go on and keep doing what she wanted to do. She looked to the pavement and saw that her toenail was chipped; she’d get a pedicure before heading to Randy’s house. He noticed things like ragged nails. Billy didn’t give a shit, but Randy—and her mother—did. She looked up, saw the clerk watching her from the window. Katy smiled, gave a little wave, and went in.

Shuffling through the racks of clothes inside, she kept thinking she shouldn’t spend the money. They couldn’t afford it. “I don’t know, I don’t know,” she muttered to herself as she rifled through hangers holding tops and skirts.

Then the clerk was suddenly beside her, said, “Can I help you?”

Katy jumped. “I don’t know,” she said. Then she looked at the woman, smiled, reached and squeezed the woman’s shoulder. “I’m sorry. It’s just I’m going a little nuts. I’m about to get married and all. Prewedding jitters, I guess.”

The clerk nodded and said Katy had a pretty ring.

“It was his grandmother’s,” Katy said. “The diamond’s not that big, but I like the little designs in the gold.”

“You buying stuff for your honeymoon?”

Katy shook her head and moved hangers across the rack. “Taking a little trip back home. I like it here, but sometimes I feel like Dorothy, want to click my heels, close my eyes, and go home. But then once I’m back there, I know I won’t like it. I’ll know I should be back here. No matter where I am, seems I always want to be someplace else.” Katy looked up and sighed. “Know what I mean?”

The clerk, a sweet-looking older woman, smiled and said, “Tell me about it.” The clerk offered a little white top. “This will look great with your tan.”

Katy took the top. It was cute, cut to show off her shoulders. “I just don’t know if I’m the marrying kind.”

“Oh, you poor young girls,” the clerk said. “You just have too many choices these days.”

“You sound like my mom,” Katy said.

“I don’t mean to lecture,” the clerk said. “It just seems to me these days there aren’t any rules.”

Jesse studied her truck. The Tennessee license plate said, “POSITIV.” Optimistic was good. They went along easy. And it could take days before her truck got into the system back in Tennessee. Perfect. He laughed and sang in a monotone, “Over the river and through the woods . . .”

Mike lit a cigarette. “You one crazy motherfucker, man.”

Jesse waved a hundred-dollar bill and motioned to Mike to move the car closer. “Now, you keep your mouth shut. If she asks, you look stupid, say we just gotta take the car to your granny’s house. Now move.”

Mike’s hands trembled as he gripped the wheel. “Why’s it got to be my granny?”

Jesse leaned forward, his eyes on the store. “Come on, we’ve got a job to do.”

Mike nodded. He was the driver. He told himself that no matter what came of this, he was just the driver. They needed her truck to hit the pawnshop. Get guns, get cash from Jesse’s friend Zeke. Then Jesse could skip town and run back to Atlanta the way he always said he’d do, and Mike would have some cash to buy groceries for his granny, maybe fix his car, score some more weed. “A simple plan, man,” Jesse had said. But Jesse was always saying, A simple plan, man. Jesse made it all sound easy and clean. Mike knew him from juvy. Mike knew Jesse had been behind that dude in the laundry getting stabbed to death with a laundry pin. The guy was always wanting to suck somebody off for cash. But when he hit on Jesse, he hit on the wrong man. When the word got out about some fucker—even a fag—dying like that, stabbed two hundred times with a laundry pin, people said, “Man, that’s fucked up, even in here.” Jesse just shrugged, said, “Everything got a reason, man.” Mike wished he could be like Jesse, all fire and wires and sparks inside. But cool somehow, like the cool blue of a gas flame.

Jesse laid the hundred-dollar bill on the dash, stretched his arms, and cracked his knuckles. With batting gloves stretched tight and smooth on his hands, he looked like he could be ready to knock a fastball out of the park.

Mike watched the glass door of the store. It didn’t seem right to use his granny like bait. Jesse had said he wouldn’t hurt whoever they hit, but Mike knew Jesse’s need to hurt whatever he held in his hands. Except dogs—he had a thing about dogs. And kids. Little kids. Mike hoped maybe that girl inside would be lucky, have a dog in her truck. Jesse wouldn’t go after a girl with a dog there beside her. Mike looked toward the truck. Then he got to wondering if the truck color was called sky blue or robin’ s-egg blue. He’d always liked that color on a truck. He felt Jesse staring at the side of his face. Jesse had a look that really could burn. “How do you do that, man?”

Jesse dropped back and leaned against the passenger door. “What?”

“That thing you do with your eyes.”

Jesse smiled. “Told you, man. I’m the devil. Don’t know why folks have such trouble believing a thing like that. They’ll believe just about anything but that.” In one quick move, he popped the glove box, reached under the papers, and pulled out a bag with a couple of tight little joints rolled and some loose weed. He looked Mike in the eye. “I knew you were stoned, you fucker. You get all paranoid and fucked up when you smoke. I told you, lay off this shit till the job’s done.”

“I don’t get paranoid. I just think about things.” Mike watched the storefront while Jesse shoved the weed in the pocket of his jeans.

“Here she comes,” Mike said as Katy walked out of the shop. She slipped her sunglasses on.

Jesse watched her, thinking, Ignorant, not looking where she’s going, too busy digging for keys. Not seeing a damned thing.

Jesse grabbed the hundred-dollar bill. “Amazing what some folks will do for a buck.”

Katy stood outside the store, happy with what she’d bought: the little white top, a bra and panties, and a short black skirt that would show off her legs. Randy always said her legs were her best part—well, not her best part. Then he’d laugh. Katy looked back toward the store, saw the clerk standing there watching, thinking Katy was some kind of criminal or nut just because she’d wanted to use the restroom to change into the new underwear. The woman had backed off, looked at her like she was some kind of whore, said, “What kind of woman needs to change her bra and panties in a store?” Katy had just said, “Never mind,” and figured she’d change at the McDonald’s down the road. She knew Randy would like the matching black lace bra and panties. Randy liked it when she took extra care to dress for him. He liked most everything she did, except taking something without asking. Once it was just a cigarette from his pack on the table. And then the shirt. He’d been really pissed about her taking it when she’d left his house that night. But he was asleep, and there was a cool rain falling, and she needed something over her tank top. So she just picked up his shirt from the floor. She told him she’d return it, and he said that wasn’t the point. Now it was in the truck, just picked up from the cleaners because it was a Brooks Brothers. She’d take it back, and she’d surprise him with a nice clean shirt and new black lace underwear. The clerk came out of the store, said, “Miss, why are you standing here?”

Katy laughed. “Ma’am, I’m just standing here thinking about a man. Don’t you remember just standing and thinking about a man?”

“Well, I’d be more comfortable if you did your thinking someplace else.” Then she gave Katy a look that meant nothing but business and went back inside.

Katy laughed and headed for her truck. She hoped Billy would work late. She’d need the time to get to Randy’s, the grocery store, then home to clean up and make that lasagna and run him a bath that would make him forget they’d ever had a fight. The good wife. She’d make him the good-wife meal. Just like her mother. But she didn’t want her mother’s life. So what the hell was she doing?

She got in the truck, found her keys, and wished she had her cell phone. If she had her phone, she’d call Randy to say she was coming, and then maybe she’d call Billy to tell him she was making the lasagna he liked. She knew it was messed up. She looked at the keys in her hand, realized she was sitting there in a sweat, an idiot in a truck, baking in the heat.

Katy flinched when Jesse opened the passenger door and jumped in.

He tossed the hundred-dollar bill in her lap and smiled. “Mind giving me a ride?”

“What?” The plastic bag of clothes crumpled to her feet.

“I need you to follow that car. It’s kind of an emergency, and taxis won’t run to where we need to go.”

She studied his face. Good-looking and smooth. “You’re sitting on my boyfriend’s shirt.”

He lifted the shirt, smoothed it across his lap. “Sorry,” he said. Then he smiled a smile that was just a little bit devilish. “Come on.” He gave a little shrug like a boy. “It’s just a little drive.” Yeah, he was cute, and he knew it.

She glanced back at the white Datsun rumbling behind the Dumpster. The driver looked like a kid, soft round face, big dark eyes staring at the man beside her.

“Come on,” he said. She turned and looked into his eyes, green flecked with black and looking straight at her. She’d always had a thing for green eyes. She tried to guess his age, early twenties, she figured, younger than she was, but worn. He was hard-looking, like a man who didn’t eat enough real meals, a man who worked out in a basement. He had a scar on his cheekbone, a little crescent shape. But what a mouth, pretty lips that curved in just the right places. The kind of mouth that knew just how to kiss. Pushy but firm and soft.

He smiled, leaned a little closer. “Yeah, I know. You like my face. I get that.” He picked up the hundred-dollar bill. “But I’m not looking for a date right now. I just need you to follow that car.” She liked the smell of him, clean but that man smell underneath.

“Why should I follow that car?” she asked. Katy had tended bar for years. She was used to guys wanting things. Asking questions was the best way she knew to make them stall. Men, no matter what they were after, always liked a little time to talk.

“Why?” The bill dropped into her lap, and he eased back into the seat beside her. “Don’t you need the money?”

“Well, sure, but—”

“Well, sure. Yes, you need the money. The thing is, my friend there, his name is Ronald, and I’m Brad.” He offered to shake her hand, and she almost took it, but she kept her hands on the steering wheel. “Okay, then, I understand your caution, some strange dude jumping in your truck—”

She laughed. “Well, yeah.”

He smiled. “You see my friend there, Ronald, he’s a little nervous. His granny, she’s sick, and she lives way out there in Whitwell. Out by Lake Waccamaw.”

Then she grinned, sat up, looked around. “Is this a joke? Where’s Randy?”

“I don’t know no Randy,” Jesse said. “What you talking about?”

“Randy. My friend. He likes to play little tricks on me. He lives out by Lake Waccamaw. I drive out there sometimes.”

“That’s nice,” Jesse said. “It’s real pretty country out there, isn’t it?”

She nodded. “Yeah, there’s something pure out there. No tourists. Just trees and water and sky.”

“And Randy,” he said. “But I guess you just drive out there for the nature and all.”

She turned to him. “Look, I’d like to help you out, but I gotta get home.”

Jesse shook his head and leaned closer. There was a softness to him, but a confidence. She liked that soft confidence in a man. She breathed that scent of him. He definitely knew what he had. He sat back and looked out her windshield as if this were just another conversation. “You got a chance to do something good here. I saw your license plate—POSITIV.’ You like to think positive, right?”

“I try,” Katy said.

“You like to do good things, right?”

She nodded, looked back at the other guy in the car.

Jesse sighed. “Well, Ronald’s granny, she’s sick, and he’s got these groceries in his trunk, and he’s gotta get the stuff to her, and if he makes it there, he can get a neighbor to work on the car.” He nodded, rocking in the seat beside her. “See, she’s waiting, and we’ve got these groceries in the trunk, and it’s a long ways out there through farm country. And that car, it’s always stalling out, and you got no idea how bad that can be in this heat.”

It sounded like a good story, but there was something off. “I need to get home,” she said. “My fiancé—”

“What about Randy? Nah, Randy isn’t your fiancé.” He said the word mean and teasing. He lifted the hundred-dollar bill and held it to her face. “For your gas and trouble. It’s just forty-five minutes from here. But then, you know that ’cause Randy lives out there, and you like to drive out and see him.”

She studied her hands on the steering wheel. The engagement ring shone in the sunlight. Something was wrong. This felt like a joke. It had to be a joke. Maybe it was Billy’s joke. Maybe Billy had found out about Randy. Maybe Billy somehow knew where Randy lived. “Is this a joke?”

“Nah, man,” Jesse said. “This is serious. Listen to that car of his.”

She listened to the chugging, staggering sound of the engine. “I’m sure it’s something simple,” she said. “You can just pull up there to a station. You could use some of that hundred dollars to fix his car.”

He smiled again as if he were telling her a joke she just didn’t understand. “Not when we can get it fixed for free. And besides, I can’t keep track of the money he owes me.” He opened his palms in a little helpless gesture. She studied that hundred-dollar bill. “It’s the principle of the thing,” he said.

“I mean why would I want to drive out to Lake Waccamaw?” she said. It was just too strange that Lake Waccamaw was exactly where she was heading as soon as she changed into that new underwear. He waved the money again, then shrugged, made a move to get out of the truck. But he didn’t leave. He paused, looked back at her.

She reached for her purse. It lay open between them.

“Look,” he said, “nothing funny is going on here. We just need you to go along in case the car dies. We can fix the car for nothing if we get out there. Ronald’s granny, she’s waiting, and if we don’t hurry, that milk in the trunk is gonna turn. I need a ride, that’s all.” He dropped the hundred dollars into her purse, zipped it tight, and tossed the purse into her lap. “There and back,” he said. “And tonight you and your fiancé, or Randy, can go have a steak dinner on me.”

“I don’t eat steak,” she said.

“Tofu, then.” He smiled. “Go have twenty tofu-bean-sprout suppers on me.”

He was really good-looking when he smiled. Like some rock star. Flashing eyes, sandy hair that fell in his face. He had country-boy good looks, the kind of face that promised wild rides in fast cars though green hills. Definitely the type she liked. “Come on,” he said softly. “My friend over there, his granny’s waiting, and she doesn’t have a phone. All you gotta do is start the engine and pull out, follow that car.”

She clutched her keys and took in his clothes, Polo shirt, good jeans, Nikes that looked brand-new. At least he had good clothes. And he was polite for a guy who’d jumped into her truck. She sat back. It was a risk. But it would make a great story to tell her friends. And Randy, he’d love it that she’d taken such a risk and made money doing it.

“A hundred bucks. How else you gonna make a hundred bucks so fast?”

“All right,” she said. “There and back.”

“There and back.” He laughed.

She started the engine, glanced over and saw the nod he gave the other guy, not happy but intent. She wished she could call Billy, tell him where she was. If she could call Billy, she wouldn’t go to Randy’s. If she could call Billy, she’d get rid of this guy and head straight home.

Katy backed out and pulled in behind the Datsun. Jesse cracked his knuckles and sighed. She saw the batting gloves. She mashed the brakes, kept her eyes on her hands gripping the steering wheel.

“What’s wrong?”

“Why are you wearing those gloves?”

He opened his hands. “Yeah, not exactly sexy, right?”

She nodded, watched his face for a lie. He glanced at her, embarrassed. “I’ve got this skin condition. My palms sweat, get these bumps that open up.” He gave a little shake of his head. “Not pretty, kinda like poison oak. I have to keep hydrocortisone cream on when it acts up. Keep a bandage on them. These gloves, they protect the sores.”

“That’s awful,” she said.

He shrugged, put his hands on his thighs. “It’s all right. It clears up. Just flares up with the heat.” He smiled. “Now you know my secret weakness. What’s yours?”

She felt herself blushing, shook her head.

He gave a little laugh. “That’s all right. I can guess what your weakness is.”

She smiled at him, liked that little secret game of flirting, not flirting, just working that line between yes and no. It wasn’t her way of mixing drinks that made her the best bartender in town, it was her way of mixing up the men, keeping them guessing. She looked away from him. “You think you know who I am?”

“Yep.” He settled back, buckled his seat belt. “Don’t you buckle up for a ride? You really ought to.”

Katy reached for her belt. “My mom made me have these installed. It’s an old truck.”

“I know,” he said. “We’d all be better off if we listened to our mommas more often.”

“Yeah,” she said. She started to press the gas, waited.

“But mommas aren’t right about everything, are they?”

“No,” she said. Her momma had never approved of any guy she’d ever dated. What did she want? For Katy to marry some professor like her dad?

He nodded, looked ahead as if they were already moving. “You got to trust me on this.” He reached out the window and motioned for the guy in the Datsun to move on.

“Trust you?” She laughed and pressed the gas and followed the car into traffic on the highway that would soon have them all heading out of town. She had a sick feeling in her stomach, knew what she was doing was dangerous. But she’d done dangerous before. Frank had pushed her into doing things way past anything like safety. And Randy, hell, Randy was nothing but a risk. But she liked to take risks, liked that jangling feeling in her belly and something sparking behind her eyes.

She told herself not to panic, just the way she told herself not to panic when her daddy played his hunting games with guns. They lived in the country, so nobody really worried about guns going off. Boys were often out shooting cans off logs, road signs, possums. Her daddy was just another one of those boys grown up. He would sit at the open window of what he called his office but was really his gunroom. He’d keep his eye on the garbage cans out back, just waiting for the scent to draw some roaming dog. He hated those dogs getting in his trash, making a mess in his yard. Then he got to where he liked to play a shooting game to keep them away. He’d call Katy in to test her. “Let’s play a little game. I can shoot that dog there or let it go. What do you want? If he gets in the garbage, it’s your job to clean it up. Or I could just shoot him. What do you say?”

Sometimes he was just testing her. He would show her sometimes that there were no bullets in the gun. He was teasing. “Let’s see how much my tough little Katy can stand.” But lots of times he did shoot. Sometimes the dog yelped and ran off. Sometimes it dropped to the ground. “If you cry, I’ll shoot.” She’d stand frozen beside him. Katy learned to chew her lip until it was bloody, but in time she learned not to make a sound.

Katy glanced at Jesse, sitting easily and looking out the window as if he were just a guy on a road trip. She told herself she’d been through much bigger dangers than this. She was a bartender, had walked to her car in the back alley hundreds of times, had talked guys out of raping her more times than she could count. The key was to make yourself human—she’d read that in a psychology class.

It had worked once when her car had broken down and she’d hitched a ride with a man who kept saying it’d be easy to rape her, leave her, and be long gone before she told. She looked him in the eye and said, “You won’t do that.” She told him she was on the way to the hospital, where her daddy was dying from a tumor in his head. She made the facts of her daddy’s suffering real in the air. And the guy believed her. He went silent and drove. He dropped her off at the hospital door and sped off before she thought to check his license plate. She was amazed. She had spun a story of her daddy’s pain to save herself when her daddy was already dead. He would have been proud of her lying like that to get to the hospital instead of ending up somewhere getting raped.

Crossing through downtown, she looked up and saw the Cape Fear River bridge. Once she crossed that bridge, she’d be in farm country. There’d be hardly anyone around. Randy would laugh at the risk she was taking. And Frank, he’d just say it was one of Katy’s new adventures. Even Billy would like the cash. But her mother would be furious.

“My mother,” she said thinking her mother could never hear about this.

“What about your mother?”

“Nothing,” she said. “My mother,” Katy said again, looking out at the suspension bridge she was about to cross. “My mother hates driving over bridges. She’s a nervous type, that’s all.”

He laughed. “And look at you. You’re not nervous at all.”

Katy headed up the ramp to the bridge over the Cape Fear River and saw the dark water swirling below. She’d heard stories of all those guys thinking they could swim the river. They got caught in the cross-currents of the river rolling out and the tidewaters of the sea rushing in. The churning force pulled them down in the river, so dark it was almost black with tannins from the vegetation that rotted on its shores. People drowned all the time in the current that whirled like a wheel. They got disoriented, couldn’t see which way was up, the water so thick and dark it sucked away all light.

As the truck surged forward, the bridge seemed to shudder, but it was her own shaking inside. Her stomach clenched, and a flash of fear shot up her spine. She saw his hands now clenched in his lap while his face looked so easy and mild. She’d seen that expression of a man about to explode: face calm, body tensed. And that look just before they grabbed a beer bottle and broke it over someone’s head. And she knew it. This was bad. This was stupid.

Slowly she reached under the seat for the little pocketknife she kept there, but all she’d ever used it for was to cut apples and cheese. She tried to slip it under her thigh to be ready. Maybe this was really bad.

Jesse saw the move, reached across, snapped up her wrist, and squeezed. The truck veered into oncoming traffic, and she pulled back into her lane. A car horn blared; the driver gave her the finger and rushed by.

He took the knife, put it in his pocket, and laughed. “What do you think you’re doing, girl? You could’ve killed us back there.”

“I’ll give you the truck,” she said.

“Really,” he said with a teasing little sound.

“You can have it. I won’t call the cops. You drive to his granny’s house. Once we get across the river, just let me out. I’ll walk home.”

He smiled. “Now, why would I make you do something like that? You’ll get home later.”

Billy would be furious. “My fiancé, he’ll be wondering where I am. He doesn’t like it when I’m late coming in.”

“Your fiancé.” He shook his head. “And what about Randy? Girl, I’m sitting in your truck and see you got Bob Marley, Lou Reed, Tom Petty, Stones, all that old rock-and-roll shit. Don’t sit there and tell me you take this fiancé shit serious.” He looked her up and down and laughed. “Damn, girl, I’m betting you got two guys on the side. Don’t you?”

She stared ahead at the highway unrolling, wished she hadn’t stopped to buy some stupid skirt for Frank and that damned underwear for Randy. Maybe if that lady had let her change in the restroom, this guy would have jumped into someone else’s car.

He was nudging her. “You get it on the side, don’t you? Don’t you?”

She gave a nod, eyes still on the road.

Jesse slapped her shoulder as if they were old friends. “Women. You got all the power, man. Don’t give a shit about nothing but a man between your legs. My momma, my blood momma, she was like that.”

Katy gripped the wheel harder, thought of yanking the car off the road, but there was nowhere to go. She glanced his way but couldn’t meet his eyes. “You’re not going to hurt me,” she said.

“Hell, no. You can drop me off and go see Randy.” He laughed, popped open the glove box. “Let’s see what other music you have.” He rummaged through a couple of CDs and, as if he’d known it would be there, grabbed the bag of pot. “Jackpot!”

She reached for his hand. “That’s my fiancé’s.”

“Right,” he said. “The bad shit we got always belongs to someone else.” He found the papers, started rolling. “I’d say we could use a little something to relax,” he said. “I knew you were into this. Smelled it the minute I got in your truck.” He reached in her purse, took her lighter, and lit up.

She felt a tear slip down her face, wiped it with the back of her hand.

“Ah, don’t worry, girl. It’s not what you think. We’ve just got a little thing to do here.”

She heard the hissing sound when he inhaled. She squeezed the steering wheel as they descended from the bridge. Back on solid ground she felt she’d left the world she knew behind. It was happening. Her mother had warned her: “You only think you’re in control, Katy. With every little reckless thing you do . . .” Katy couldn’t remember the rest of the warning. But somewhere inside she’d always known something like this would happen one day. She was Dorothy suddenly lifted by a furious wind spinning her to a terrifying new place where good really did battle evil, where a rebellious girl’s only desire was to go home.

When Katy was a girl, she believed in Oz. The first time she saw the movie, she was five years old. On the overstuffed green sofa she leaned into her daddy’s side, ate popcorn, and sipped Coke. She sat transfixed when the black tornado rolled across the prairie and snatched up Dorothy’s house, sent it spinning in a world flying by with cows mooing, chickens flapping, the mean old lady furiously pedaling her bicycle as if anyone could really outrun a storm.

During the commercial she asked her daddy if a tornado really could lift her off to another land. “Most definitely,” he said.

She asked, “Do we have tornadoes in Tennessee?”

“Sometimes,” he said, “but you don’t have to worry about that. Our house is made of brick. Remember the wolf? He huffed and puffed and couldn’t blow the brick house down.”

Katy glanced at the man beside her, now looking at the CDs she kept between the seats.

“Cool; this old truck’s got a player.”

“I had it installed. This was my daddy’s truck.”

But he wasn’t listening. “You got lots of Marley.” He turned on the accent. “You like da ganja, lady. I got good ganja for you.” He held the joint out to her.

“I don’t want any pot,” she said. “I just want to get home.”

He was studying a CD cover. “Yeah, Bob Marley, he’s cool. Black folks, white folks, all kinds of folks dig Bob.” He tossed the CD to the floor and looked out the window. She realized Randy’s shirt was down on the floor. But she didn’t say anything. He was watching her every move, and when he caught her eye, he just grinned. “You believe that Rasta shit ’bout Haile Selassie? I’ve got these black friends I do some dealing with. They talk about Selassie like he was some kind of a god.”

She’d heard that. Most people didn’t know about the Haile Selassie connection. Most thought Rasta was just a smoke-dope-grow-dreadlocks kind of thing. “I’m not sure they think he’s a god,” Katy said. “More like a messenger, I think. But don’t real Rastas see a little bit of God in everything?”

Jesse laughed, his shoulders rocking as he watched the land go by. “Yeah, a messenger. I’m a messenger. Them Rasta dudes get high enough, I bet they see a little bit of God in me.” He turned, gave her that soft grin she’d seen when he’d first slipped into her truck. “What I mean is, we can all be messengers. We all got something the world needs to hear.”

“Yes,” she said, looking at the clock. She’d be home by dinnertime. Positive, she thought, think positive. The Lord didn’t give us a spirit of fear, but one of power and love and soundness of mind. It was scripture. Her mother kept it framed by her bedside table. Nice calligraphy, with a rose drawn in one corner. It was a pretty thing to wake up to, Katy guessed.

She thought of Dorothy, closing her eyes, petting little Toto, whispering, There’s no place like home. Yes, positive. They would take her truck and leave her, and she’d find her way to Randy’s house. He was always trying to get her to do reckless things, like take a plane to Vegas with him, Cancun. He lived the good life, all right. He called her a coward, teased her about being a good wife, said if she really had the nerve she liked to think she did, she’d say to hell with the good-wife thing. Maybe this guy jumping in her truck and asking her to take him out by Lake Waccamaw was a sign that Lake Waccamaw was where she was supposed to be. But she couldn’t shake the feeling that this guy was dangerous. Anyone could be dangerous. She glanced at him, tried to sound casual. “How about we stop somewhere for a six-pack? I could use a cold beer. Make it like a road trip.”

He laughed. “Drinking and driving. Don’t you know that’s against the law?” He smiled and waved the joint toward her. “Nah, we got this. You take me where I’m going, we’ll burn this together. Just you and me. Let Mike go tend his granny. You and me, we’ll do some shit. Then like Marley says, ‘Every little thing is gonna be all right.’”

“Mike? Who’s Mike?”

He looked at her. “Ronald Mike,” he said. “That’s his name. He likes to be called Mike, but I call him Ronald just to give him shit.” He kept his eyes on her. “Relax, girl. You’re going to Lake Waccamaw. You like the land out there. You like Randy. Now, why is it you really drive out there? Oh, yeah, the land, the lake, the sky, that’s right.”

“I do,” she said. “I love the easy pace. Yeah, I do like the land and lake and sky. I like to get away from the tourists. I like it where people know how to sit back, have a drink without sinning, look at the land and relax.”

“Is that what you want? A drink without sinning and relax? You’re just like all those other tourists.”

“No, I’m not,” she said. “You don’t know me.”

“Yeah, I do,” he said.

He looked at her, grinning. A guy with that kind of smile couldn’t be too mean, could he? No, he was just a little scary. “So you from here?” she asked.

He shook his head and stared out at the Datsun ahead of them.

“So where are you from?” she said again.

“Where am I from?” he said. “Let’s just call it burned bridges. You can understand that.”

Billy believed in burned bridges, said that was the only way you moved forward. He told her, “You’ve got to burn the past, leave it all behind.” He was talking about her daddy. But what he was really talking about was Frank. Billy was teaching her how to leave the past behind. If she could just choose him. Poor Billy didn’t have a clue about Randy. Billy didn’t have any idea he’d probably be one more burned bridge she left behind in time. “Billy,” she said. “My fiancé—I can tell you don’t like that word, but he likes to leave burning bridges behind too.”

He yelled, “I don’t give a damn about Billy, or Randy, or you, lady. I just want you to stay close behind that car and drive.”

She braked and pulled to the side of the road. “I’m not going any farther,” she said. “This doesn’t feel right. I’ve got other things to do.”

Jesse mashed the joint out on the dashboard. His eyes went dark. He turned, reached behind his back, then raised a gun between them. “Damn right you got things to do.” He poked the barrel of the gun into her ribs, but his face was casual, almost smiling. “We need your truck, you see. We need you to follow us to Whitwell. That’s all. You got that?”

She sat tight and trembling. Her body felt frozen. How could she move without cracking, without breaking to pieces all over the seat? She could feel the heat of his breath between them. She caught the scent of oil and metal. Katy sat back in her seat, tried to catch up with her breathing, which seemed to take off, running out ahead of her. She told herself to stay calm. “I don’t want to,” she said.

“You don’t have a choice.” He looked straight at her, and she saw a face she hadn’t seen back in the parking lot of the mall. His eyes, empty. She thought of the alligators that sunned themselves in swamps around Lake Waccamaw, still as logs on the water, dull eyes focused on the surface, patient, blending quietly into the landscape, certain what they wanted would come within reach in time. Billy had told her to be careful walking around Lake Waccamaw. More than one hunter had been taken down by a gator waiting in the reeds. Poor Billy; he thought she just drove out there for the lake. He didn’t know about the man named Randy, whom she’d met when she’d been bartender for a wedding at some rich man’s house out there. Randy was handing out coke to the wedding party. He slipped her a tiny bag for a tip. “Just a taste,” he said. “One little taste, and you won’t want to quit.” Then he grinned and said, “I’m not talking about the coke, darlin’. I’m talking about me.”

Jesse nudged her lightly, as if they were old friends and she’d just lost the conversation.

“Please,” he said. “How’s that? Please? I promise I’m not going to shoot you. That isn’t what this gun is about. Come on, we gotta stay behind Mike there. Get going and you can tell me all about your fiancé.”

“I don’t want to talk about my fiancé.”

He touched her arm lightly. “Look here. I apologize for my brutish behavior. All right? My momma, she brought me up better than that. She’s done a lot of work to teach me manners. I just slip now and then. You know how that is. Don’t tell me you’ve never slipped.” He gave her a smile again, as if they shared a secret. “Now, come on. We’re halfway there. Put me out and I’m taking back that hundred-dollar bill. I know you need the cash.”

Katy looked out and saw the Datsun stopped ahead. “I don’t like it, but I’ll do it,” she said.

“Well, neither do I,” he said. He sat back, more natural, relaxed. “You think I like having to take care of his ol’ granny? You think I don’t have better things do to with my day?”

He stared ahead, and they sat like two lovers worn out from a fight, caught in the lull of silence. A car rushed by on the highway, disappeared in the distance and left Katy behind. Tears ran from her eyes.

“Relax,” he said. “I’m really not gonna shoot you. All I’m asking is for you to follow my friend. Look at him up there. He’s waiting. We don’t have much farther to go. And then you can go see Randy.” He tucked the gun back in his waistband. “Now, please, this can be over in no time. And you get that hundred-dollar bill. Would you just put this truck in gear and go?”

He reached and relit the joint. “Just take a little hit and relax. There really is nothing going on here but you helping a couple guys out.” He offered her the joint. “I promise.”

He watched her put the joint to her lips, watched her take a hit, hold it. “All right,” he said with a laugh.

Up ahead Mike rolled down the window of his car and looked back at them. Jesse reached his hand out the window, gave a thumbs-up sign.

Katy asked. “Why don’t you ride with your friend in his car? Why do you need to be here with me?”

He shook his head. “You really need an answer to that question?”

“Yes.”

“All right, then. My friend up there, he farts a lot. I hate riding with that man.”

Katy laughed. “No, really,” she said. She handed back the joint; she didn’t want to get high, just needed to level her nerves.

He took a hit, nodded. “Really.” He exhaled. “And, well, truth is, I guess I did want to make sure you came along. Now, would you please put this thing in gear and go?”

“You won’t shoot me,” she said.

“I swear by all that’s holy and all that’s not, I will not shoot you.” He mashed the joint out, flicked the roach to the floor. “Can’t have us getting too buzzed for the ride.”

Katy drove, thinking, The Lord didn’t give us a spirit of fear. . . . But with each passing mile she felt she was sinking into some soft, wet pit. Nothing sudden as an earthquake but a slow, steady sinking like a million-dollar glass house in the Hollywood hills, shifting, slipping slowly, quietly, in a mudslide rising like a tide from the earth.

She scanned the horizon for a car. Her hands shook on the wheel.

“Relax. Just tell yourself you’re being a good little Girl Scout, doing the public some kind of good.”

“I never was a Girl Scout,” she said.

He shifted. “Nah, I know your type, one of those misfits. You could play the game, but I bet you never felt you really fit in. Probably always dreaming of some other life, some other place you’d rather be.”

Fear hummed like a nest of bees whirling in her head. She couldn’t breathe. “How do you know that?”

“I pay attention. That new-age bullshit on your tag. ‘Positive.’ Like you really believe thinking positive can change a thing. You believers, man. You make me laugh. And this truck of yours. It’s the kind of car a girl who likes to dream of going places can afford. I bet you’re saving money for trips all the time. And never go anywhere, right?”

She could feel his eyes. She blocked his view of her face with her hand. She knew he could see everything she was. “Are you a friend of Randy’s? Have you been spying on me?”

“God, no, I’m telling you I just notice things. Like your fake fingernails. Fake and shiny but got dirt all under ’em. You got this thing about looking good, but you still like to spend your time playing in the dirt.” He poked the back of her hand with his fingertip. “You probably grow all those herbs healthy people eat. Basil, rosemary, dill. My mom, my legal mom, not the blood one, she grows that stuff.”

Katy looked at him. She had been transplanting seedlings to the garden that morning. Like his mother. He had mentioned his mother. She felt a little relief.

“I do grow basil. I keep meaning to make pesto.” She thought about the basil going to seed in her yard. She’d grown it last year too. Always talked about making pesto. Her mom made great pesto, but Katy never got around to it. She could never collect all those ingredients at the same time, so the basil kept growing until it went to seed and she’d tell herself she’d try it again with basil she could buy from the store.

“I look at you and figure, this is a woman believes in things.” He shook his head. “You were one of those little girls who set out cookies for Santa Claus, thought fairy things like Tinker Bell lived in the woods and the Easter Bunny really crept around your house hiding those eggs. You probably believe in things like guardian angels too.”

She looked out at the flat, empty highway. “I don’t know. I did believe in fairies when I was a girl.”

He looked out his window. “Me, I was always playing pirate. Eye patch, scarf on my head, stole this big ol’ kitchen knife.” He laughed. “I scared the shit out of some of those kids. ‘Shiver me timbers,’ man.” He laughed and propped his foot on the dash.

She didn’t want to hear about pirates and kitchen knives. She stared at his running shoes. “You an athlete?”

He laughed. “Yeah, breaking and entering—that’s my sport.” He lit another one of her cigarettes. “Nah, girl, I’m funning you. Football,” he said. “I play football.” He lifted his chin, exhaled. “Love it when the defense crumbles and you’re out there, man, just running.”

She looked him over, wouldn’t have guessed him for football. He was too little, too lean; she figured him for a wrestler, a runner, or some skinny guy who just buffed up with weights.

He turned to her. “I know what you’re thinking. I’m too little for football, right? But I can run like a mother, and I’m stronger than you think.”

Up ahead the right blinker of the Datsun flashed. “Here,” he said. “Get off and follow him.”

“This isn’t the way to Whitwell. Lake Waccamaw is just up there.”

“Shortcut,” he said. “This is farm country. His granny, she lives on a farm outside Whitwell.”

She followed the car, could hear her little-girl self crying inside, but she kept going. She followed his instructions, did what she was told, and the roads grew smaller, the land more empty with each passing mile. “I don’t want to do this.”

“But you’re doing it,” he said.

She trembled, wishing she had paid attention to the exit number, the route number, something. She looked out, saw some kind of abandoned factory. A power station maybe. Lots of electrical towers and power lines that seemed dead now. She’d remember this. If she just paid close attention to where she was going and could get back to this, she could get back to the highway. Lake Waccamaw wasn’t too far. Randy’s house was just south of the lake. If she focused, stayed steady, she’d get there. And Randy, he’d make it all right. He’d make her forget this whole stupid mess. She drove in deeper darkness and realized she’d forgotten to pay attention. While she was thinking about what she’d do later, she’d lost the sense of where she was. A dark wave rolled up from inside her, as if she’d been snatched by a current. The Cape Fear River. She had felt it then. She might have gotten help if she’d done something to get attention, but now she’d been carried too far out for anyone to hear her call.

Katy kept her eyes on the Datsun. Maybe they’d just rob her, maybe rape her, leave her to find her way home. But she was lost; she had no idea where she was. She looked out at the fields going red in the sunset and saw herself rising in the air, like Dorothy in that little house lifted by a storm. She’d get through this, like Dorothy, and she’d wake up, find herself settled in a bright new land.

Jesse flipped through her billfold. “Man, you’ve got no cash here. Not a dollar here.”

She slapped at his hands. “Stop it. Stop going through my things like I’m not here.”

He smacked her arm hard enough to make her bite her lip, grip the wheel. “Now, don’t you start pissing me off.”

“All right,” she said, “I’ll pull over. Go ahead and shoot me. I’m not scared.”

He laughed, yanked the gun out and waved it in the air. “Damn gun doesn’t work. It’s just a prop, man.” He pulled the trigger. Nothing happened. It was jammed. “Scared you, didn’t I? See, I told you I wouldn’t shoot you. Look here, now. It’s almost over. He’s turning down that dirt road.”

She looked to where the Datsun was turning, west where the sky hung in purple and pink waves. The gun doesn’t work, she thought; she’d driven all those miles for a cute guy with a smile and a gun that didn’t work.

The Datsun slowed, took another turn, and Katy thought to just plow straight ahead to get to anywhere but where they were going. Jesse was shaking with quiet laughter. “All you got to do is raise a gun to somebody’s face. They put the bullets in it. They see their heads blown off. All you got to do is raise the gun. Devil works likes a magician, man, half the game is sleight of hand. Most people. You believers. You do all the rest.” He waved the gun in the air. “This is what you get for believing in things.”

She kept driving down the narrow gravel road, saw a field of fallen trees as if a great wind had leveled the land. She remembered she was in hurricane country. Every year the coastal towns prepared for the seasonal storms that spiraled out at sea, gathering up strength like a fist rising to slam the coast.

She scanned the horizon for any sign of something she could know. Then she saw it. The radio tower, just a few miles away maybe. If she could get to that tower, she’d know where she was, and Randy’s house was only a few miles from that. She sighed. She’d be all right. The tower, there it was back there, a sign that she wasn’t as lost as she had thought. She followed the car down another gravel road, but it curved as if it might go someplace. She kept watching the land for a sign of a house, a tractor, a powerline, anything that looked like someone could be around. The road kept curving, surrounded by nothing but thickets and brambles and trees.

“Where the fuck is he going?” Jesse leaned forward in his seat.

Katy said, “I thought we were going to his grandmother’s house.” But she didn’t believe the words any more than she believed in that hundred-dollar bill, which was probably a fake. She looked out at the land, thought the trees looked familiar. Then she saw a house. A little brick house. Once they stopped the truck, she could run to that. Driving on, she saw an old tire on the ground, thought maybe she’d seen that before, but in the country people were always just leaving their old stuff scattered in the fields: tires. washing machines, old cars. At least with all this junk, people couldn’t be too far away. And she could run. She’d been a real good runner back in school.

Jesse leaned out the window, looked around. He yelled, “You’re driving in fucking circles, man. I thought you knew where you were going.” He sat back in his seat, kept his eyes on the Datsun. “The fucker is stoned,” he said. “That’s another reason I hate riding with him. When’s he’s stoned, he doesn’t know what the hell he’s doing.” He gave her that smile. “Don’t you worry. He’ll get us there. It’ll be all right.”

The Datsun eased to a stop, then made a quick turn down a little road she could hardly see for the trees.

“See,” Jesse said. “We’re getting there.” The rutted road led them through thickets and overhanging branches so thick she was sure there would be nothing but more trees and dirt and rocks where they were going. And the crying, that stinging ache, rose behind her eyes. The sky was shrinking to a thin patch above. She looked left, right. All she could see was trees. She wished she’d paid attention to where the sun was when she’d seen that house. She hoped the guys would do what they wanted and leave. She knew they’d take her truck. Billy had warned her to keep the doors locked. She glanced at the man sitting in her truck. He might rape her. But he might be too stoned for that. If he did, she’d go still so he wouldn’t hurt her. And when she got her chance, her first chance, she’d run. She’d take whatever he did, play along, but at the first chance, she’d run. She might have to run a while. But she’d live. She’d been through worse than this. She’d live. She’d get to Randy. Maybe the whole point of this was to get to Randy, who’d give her the nerve to leave Billy behind. If she could be with Randy, she could get over Frank. There was always a reason for things. It just took time to understand. She’d never really wanted the safe guy. Poor Billy. He loved her. She wished she could want the safe guy. If she’d wanted the safe guy, she wouldn’t be stuck in a truck with a guy who’d do God knew what if he got the chance. But she was stronger than he could guess. She was. And smart and fast, and she would do whatever it took to get out of this mess alive.