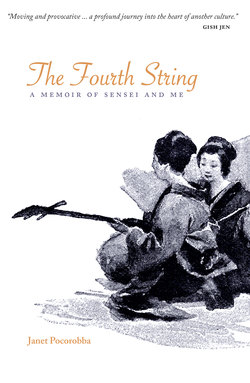

Читать книгу The Fourth String - Janet Pocorobba - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3 … an ongoing conversation between the living and the dead …

ОглавлениеI once stayed at a Zen temple where it was forbidden at meals to pick up a dish with one hand. The slight adjustment was profound. With no chance for preoccupation with the other hand, no grabbing lightly while lost in thought, I was brought more fully into what I was doing. It made the act devotional, which could perhaps be defined, for lack of better words, as doing something “with both hands.”

In those first days after meeting Sensei I began to live in Japan “with both hands.”

I still sat on the bed in the mornings, sipping my ritual cup of Nescafé while staring out at the waves of Sagami Bay. I walked to school with Larry, up the hill, past the cemetery, to our campus near a tea farm. But now I met the eyes of women on balconies trimming bonsai or hanging laundry, who called out, “Itterasshai!” the ritual leave-taking phrase, “Please go and come back safely,” and answered, “Ittekimasu!” “I will go now and return.”

I started taking my students to dinner in Chinatown, or little pubs where I could pester them about Japanese music. I promised Larry no baseball or bowling outings. We sat at these gatherings, surrounded by a pod of students asking, Did I own a gun? What was my favorite movie?

None had seen a shamisen, but they told me what they knew. The sitting position, on the knees, would be painful. It meant discipline and hard study. And then they offered words like gaman (staying power), and seishin (spirit). They wished me luck. Ganbatte! They were happy I liked Japan. One girl pulled me aside. I will never forget Etsuko, tall and willowy, with slanted eyeteeth and a glamour somehow despite them. She’d once told me her skin was yellow because of a problematic “river.” Etsuko threw her hair over one shoulder and said the traditional arts were wife training. “Japanese wife needs to learn obedience and duty.” Etsuko and the other girls were looking for husbands with the three “highs”: tall, high salary, the high nose of a foreigner.

I wove shamisen into conversations with school personnel and 7-Eleven clerks. “Erai! ” strangers said, akin to “Good girl!” or “Omoshiroi …” a word that meant both “interesting” and “funny.”

I went looking for a book on Japanese music. Not because I didn’t trust Sensei, though the whole situation was so unreal, so unexpected, that I had to wonder. Why would she teach music to foreigners who would soon leave? Were there really no scales, no ways to practice or warm up?

I took a crowded elevator up to the fifth floor of English books at the Kinokuniya store. In the spot on the shelf where the professor’s book on Japanese music would be was a blank. It was out of print, said a salesgirl. I wandered into a nearby department store and followed the signs for musical instruments. Shamisen were displayed on glass shelves under spotlights, their necks long and glossy. A salesgirl showed how it came apart in three pieces and was easy to carry home in a suitcase on an airplane. I shook my head and wandered into stationery, where I bought a black leather techo, appointment book, that fit in the palm of my hand and came wrapped in a box like a Christmas present. In the square for October 16, 1996, I wrote with the attached pen, “Concert in Kamakura” and looked at it from time to time, a place in the sea of blank pages where I was expected to be.

“Performance brings out peoples’ personalities,” Sensei said when she called with updates. I listened, absorbed into her concerns about food, clothing, people, transportation. Who was a vegetarian? How many kimono dressers did we need? And most of all the weather. “Out of my control,” she said mournfully, and spoke of autumn typhoons that could race up the coast and deluge us and our instruments.

Larry was there on the periphery of it all, quiet, easygoing, preparing his lessons and coming in from his reading to the spare bedroom where I’d set up to practice singing. Despite my pleas that I couldn’t sing, Sensei had handed me a cassette tape on my way out the door. Ame no Goro, “Goro’s Rain,” was composed in 1841 and retold the medieval legend of two samurai, the Soga brothers, who avenge their father’s death. In the accompanying translation, I saw a lot of “drenched dew” and “knotweed.”

“Sounds more like a love story,” I said.

Sensei sighed. “It’s always a love story.”

“What’s that noise?” Larry said when he came in. “Sounds like someone’s been stuck by a cattle prod.”

“It’s Goro,” I explained. “These are his last moments before ritual suicide. You’d be sad, too.”

“Oh,” he said and left.

If the sudden and unexpected connection to everything around me felt like a door was opening, it was the return to the music that pulled me inside. I had forgotten what it was like to be in a piece of music, going back and forth over it, honing, polishing. It was like a limb had been missing and resprouted anew.

When Larry left, I laid out the score at my knees. To say that I could not sing the song is too simple. What sounded easy was extremely difficult to imitate. As on the shamisen, I was focused on the notes rather than the spaces between. And the notes didn’t seem to be notes. Not like notes I knew, that sat on a staff and didn’t move, that had a value and a shape, a place, up or down, high or low, sharp or flat.

All I can say is that the notes of the Japanese voices on my tape seemed to contain all these qualities at once. As soon as they began, they seemed to move, away from their origin and toward their destination but in no straight line I could hear. They seemed to ascend while descending, stop while continuing. I can think of no other way to put it, only to say that it was very complicated. And seemed completely possible until I tried to do it.

I rewound, listened again. I broke a page down into a line, a measure, a beat, a breath, straining to distinguish the most imperceptible differences. Soon exhausted, I would give up and roll off my knees.

And yet the tune was infectious. It followed me everywhere. On my steps up the hill to school, making tea in my room. If I’d been listening and then gone out walking, I heard the notes in the sound of a shoe on the stairs, a murmur in a shop, the trickle of water, a bird’s cry. The result of my utter failure to produce the note, I see now, was the beginning of listening intensely.

Sensei told me not to worry.

“But I don’t know where the music’s going. It seems to just do what it wants.” I wrote a Western staff in an attempt to place the notes. But even with that, using the only language I could use to describe what I was hearing, I failed. It was like I had the wrong ears to hear it.

And the overall quality of the voices and singing style was impossible to render. Where Western voices sail clear to high C, and treasure clarity and polish, all I can say is these voices sounded broken, tortured, as they revved in the throat and bleated like a raw wind over the sea.

Each time Sensei called with updates on concert preparations, I expected her to reveal some key piece of information that would unlock the technique, but none came. I hoped to learn more when I returned to her rooms the next Saturday for another lesson.

It was only a week later, but autumn had arrived. The skies were clear and the air freed from summer’s clutches. I followed the route she had shown me, down the busy road, Kannana-dori, which I named that day “Lucky Seven,” passing the barber shop and the car dealership, where Ichiro in his Giants uniform was still smiling on a flag. At the cherry tree at the entrance of her housing complex, I turned in and headed up the three stairs and down the concrete veranda.

Outside the steel door to #105, I heard two shamisen snapping crisply. The door rattled when I knocked.

“Hai, dozo!” Sensei yelled, not stopping her teaching.

“You have to wait,” she said to the tall foreign woman on the stool as I slipped off my loafers and stepped up into the kitchen.

“Space!”

The woman was Denise, a six-foot bashful blonde from Georgia. You’d never know she was about to dance as Goro in the show. She chose male dances instead of female, because of her height, but I suspect she preferred flashing muscle and downing cups of sake to permissive mincing and gazing at the moon.

“I’m a bull in a China shop around here,” she sighed.

Her dance school was the same as Sensei’s mother.

“All connected,” Sensei beamed.

“She’s a national treasure,” Denise told me later. She only came to learn shamisen to be around her.

Soon arriving were Lisa, an exchange student at Waseda, and a tall man Sensei called Douggie, who handed her a box of Hershey’s ice cream pops that she tucked into the freezer. Most of her students were Americans.

Over tea and rice crackers, they talked about another student, The Enchanting Creature, who apparently had gone missing. Then it was time to rehearse.

In the music room, Sensei, Doug, Lisa, and I kneeled on a line of cushions, while Denise struck a pose in the empty middle room. Sensei cued a tape and the music began, somber, rigidly organized, and baffling. Next to me Doug plucked a shamisen. Lisa tapped a hand drum next to Sensei, who was playing a small round drum with two long sticks. It was hard to hear the taped music over all the instruments and Denise stomping under her umbrella. My urge to understand pressed on me. I blurted out notes, trying not to sing in the blank spaces.

At the end of the song, Sensei kneeled beside me. “You can sing kind of quietly, how do you say, lip synch, it’s OK. Most important is to look professional.”

As in the shamisen lesson, my concern was with the note. That is what would either embarrass me or not. It was the one thing I had control over, I thought. But it was what fell around the note that was important, like the form of the singer as she sat and fulfilled her role. This was about not embarrassing others.

A form, or kata, is a precise exercise, a foundational stroke. “Kata is a boundary or skin,” my journals say, “where the individual heart meets collective experience.” Kata are what allow a beginner to go onstage, to join the flow, providing safe harbor in unknown seas. The kata sets you up for a lifetime of artistic practice. A kata was reliable.

While the others took a tea break and stretched their legs, Sensei demonstrated.

I took some issue at first with being shown how to sit and turn a page. But it soon became clear. I was moving too much: bending, reaching, turning. I had to do one thing after another. Linear, slow, literal.

When it came time to sing, I was to pick up a tiny fan Sensei set by my knees. The fan was never to be opened. I should find it with my fingers not my eyes, and when contacting the smooth bamboo rib under my thumb, draw it gently up into my lap where my left palm should lay open to receive it.

We tried again and the music unspooled like a heavy wave, rising and falling around us. Reach but not move. Find but not look.

This was the beginning of the great funneling, the whittling of impulses into a first form. Here, without the basic vocal training or ability to even follow or hear exactly where the notes were going, I was pruning and taming the body into a recognizable shape in the world. A kata was doable, even if the music was not. It hallowed my actions, giving something trivial great weight and importance.

Getting inside things without words. Infection without understanding.

I have often wondered why Sensei invited me to perform when I knew so little. Did she see a talented person who might be useful to her mission? Or a girl full of desire who needed a form to realize those desires in the world?

Embodying a kata meant being recognizable in her world, and in Japan. With effort and time, you could polish, along with the actions, your true intention.

“How much do we know reality?” she said one day years later at a diner in Vermont where she’d come to visit. Among the plates of lasagna, scalloped potatoes, and apple pie, she said, “This is reality, but in a way, just food. We are anxious every day. What is normal way? We are looking, but it doesn’t exist. That’s why, curiosity and desire are a necessity.”

Instead of duty, she meant. If one is to find one’s own true path, one has to bear desire. Be able to contain the dream.

After rehearsal we were whisked off to the theater. Sensei had ordered us tickets for a one-curtain show. The woman had plans. This was not meant to be entertainment but benkyo, study. Kabuki theater was the historical genesis of Sensei’s music.

The dance was Musume Dojoji, “The Maiden at Dojo Temple,” Sensei explained on the train, leaning over her tote bag brimming with music scores and snacks, hands clasped, as if delivering a lecture or blessing.

A woman has fallen in love with a priest. When he spurns her, she comes to his temple, pretending to be collecting subscriptions, and traps him under the temple bell and turns into a snake ghost. “Women are demons,” Sensei said, wiggling two index fingers by her ears.

Denise jumped in with the story of Okuni, the shrine maiden who invented kabuki in the sixteenth century but whose shows had, apparently, been shut down for lewdness. Now men acted women’s roles onstage.

“Women can’t play on stage at the kabuki,” Denise said. “No matter how good they are.”

“Such a feudal society. That’s why I don’t like,” Sensei said.

Today’s show would be danced by an onnagata, a female impersonator.

“Hengemono,” Sensei instructed, as we settled into front-row seats in the balcony. A female transformation play. “Most popular.”

We had opted not to buy earphone guides. We were there for the music anyway. Sensei passed out cream puffs and tea and looked around. A smattering of foreigners and Japanese sat in the balcony. Below us were three floors of seats, the first of which hugged a raised walkway that cut through the audience at stage right. This was the hanamichi, “flower path,” Denise said, for dramatic exits and entrances.

Sensei scanned the stage with binoculars as the curtain rose. There were two, a heavy formal one that rose automatically, and underneath a thinner one pulled open by stage hands.

“Lead singer is my sensei’s favorite,” she whispered. “And the drummer?” She indicated a silver-maned man whose drum ropes were violet, not orange, like the others. “Very womanizer.”

The musicians were kneeling on a vermilion carpet in two tiered rows at the side of the stage. I counted eighteen in all: shamisen players, drummers, a flute player, and singers who had the little fan closed at their knees and were the only ones with music stands reading a score. There was no conductor. All musicians faced front, unmoving. A shamisen began a slow tattoo, and a singer released a throaty howl. The spareness—the spookiness—cast a hush and we, too, stopped moving to listen.

Soon we heard the screeching of curtain hooks and a collective gasp as heads turned to look. Applause rose like a wave, and finally, creeping into our view, on the hanamichi, was the dancer, white-faced, in a flat red hat, dipping and swooning her way to the stage. She (he?) took her time, advancing, retreating, letting her long ornately stitched kimono tease over the edge. “For his patrons,” Sensei said later.

The theater remained in half-light, the color of late afternoon. People ate lunchboxes and drank small cans of tea. They stepped out and returned. The box seats were lined with ladies in kimono, and a few men, too. It all had a festive feel, like an extended picnic.

Every so often, a male voice from the rear shouted, “Matte imashita!” “I was waiting for that!” Or “Yamatoya!” (an actor’s guild name). These people were plants, Sensei said. People today did not know the plays well enough to play this role anymore. For kabuki was a collaboration between the audience and the actors, who traversed the space between them, eclipsing it, and expanding it, in dizzying spontaneous howls. In this way tradition was alive: an ongoing conversation between the living and the dead.

From time to time Sensei’s hands rose to her lap and tapped out drumbeats. I could feel the force of her concentration as her small hands pat-pat-patted, sometimes crossing each other and landing noiselessly in her lap. I think that’s when it began to hit me that Sensei was composing a life in this music. It was her personal choice. Her day job only gave her the freedom to love it all the more, to devote herself to it without question.

It took time. There was no substitute when everything was learned—“stolen”—through exposure to the art in discreet moments of witnessing or observation. The most important thing you could do, then, was to show up, to prepare yourself for learning. Even my codified gestures—legs folded, eyes down—were setting up a kind of condition so that something might sink in.

At one point, the dancer paused and knelt in the middle of the stage, her long sleeves crossed on her lap like a butterfly’s wings.

Sensei whispered, “Hikinuki, special technique … ”

A man dressed in black scurried onto the stage and disappeared behind the dancer. The shamisen entered a drone, the singing stopped. The man was moving, arms flying quickly, and then everything stopped and the dancer burst forward, as from a cocoon, her shed layer in the hands of the man now ferrying it off stage.

The risk of such a trick made me dizzy. I swooned at everything that could have gone wrong but didn’t. I was still swooning as the dancer mounted the bell in the last scene, in a silver kimono patterned with triangular “scales,” waving a demon’s trident, her white face leering at us as the curtain was pulled across the stage.

The image remained with me as we filed down the stairs with the crowds of people and stood out front to take a picture. A drum boomed and a festival flute trilled. Women in kimono were rushing to find taxis. I felt like everything was moving and nothing was moving at all, like the dance, a series of stops and starts of still life tableaux. Mostly, I didn’t want to leave the theater. I had an inexplicable longing to go back in and see it all again, to maybe never leave, as I watched Denise line us up in the viewfinder.

Sensei stood behind me, one step up, in pedal pushers and a raincoat cinched at her waist. I leaned forward on my umbrella in an Edwardian blazer, giddy. In yellow-lit windows above, I imagined the actors rubbing greasepaint from their cheeks, maybe sipping a whiskey. They would be in cotton robes and soon they would leave the theater for dinner, or home, for tomorrow they would return to do it again. Somewhere up there, too, was an old man with a needle and thread, who would stay late into the night to sew those kimono back together, stitch by stitch, until all the layers were invisible.

“Hai cheezu!” yelled Denise.

And then, somewhere between Denise’s signal to pose and the click of the flash, Sensei did something I would never have expected her to do, knowing as I did, something of Japanese life. I had visited families for maple-viewing or hot-pot suppers and found them absent of pats on the hand or kisses on the cheek, any touching, in other words, or evidence of affection.

And yet that is what she did. As the shutter clicked and the crowds found their way to trains or bars, Sensei placed her hand on my right shoulder.

How to describe the significance of this? The gesture, so small but so radical. It is hard to convey. I continue to study the picture, to see again what she meant for me. Was she claiming? Anointing? Letting me know that she wanted Western familiarity, not Japanese?

Sensei never wanted to be called a teacher, literally “the one who came before.” But that is what she was, if learning in Japan was an intimacy with strangers, those people you would never meet or know, who had, long before you, created the forms, the gestures, the kata, that you would fill. Everyone had a role, even the man in black, a propsman coming to the aid of the actor. It wasn’t important what the role was, but having a role at all.

Perhaps, this, too, was my benkyo, and what her hand meant to say.