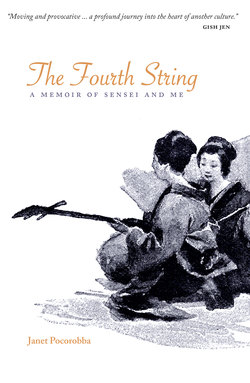

Читать книгу The Fourth String - Janet Pocorobba - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 … a companion to order and control …

ОглавлениеSensei existed long before me, as a child on the foggy foul-weathered Sea of Japan, though I have always imagined her sprung whole, like Athena, from the head of Zeus. I am surrounded by pictures of her—at her sink in her old rooms in Tokyo, with the pink gas heater to warm her water to wash dishes; walking alongside the professor under an umbrella in her chic arrow-patterned kimono coat; placing her hand on my shoulder outside the kabuki theater, an unexpected claiming; sitting by a stream in Kyoto in her pinwheel velour Beatles cap, next to where a blue heron stands.

She took me to her childhood home years later, when it was on the verge of being torn down. Out in front of the traditional wooden house was the bench where, as a girl, she ate her lunchboxes alone to escape the interior gloom. She showed me her mother’s rooms, which she’d modeled after the Imperial Villa, with papered panels and a glossy stage. Her father’s small study with its camera lenses.

“Traveling,” she called going out together, even if we were just going across town. “My spirit likes traveling, like yours does….” She saw herself differently with me, I think. I have always felt not quite natural with Sensei, yet completely myself.

That day, walking in an arcade near her house, with no music to plan, no upcoming concerts, we were talking about our pasts. “I was also,” she said, “how do you say … slut?”

Did she say what I think she said? I wanted to believe she was as desperate as I was for love. Had maybe a blizzard of men in her past. I wonder now if she sometimes said only what she thought I needed to hear. But then again, isn’t that what a good teacher does?

Sensei became my teacher, if that is what it can be called, on a hot day in September 1996. All I remember is that, from the start, it felt like something was missing. Off kilter. Not quite what it should be.

And why wouldn’t I feel that? I was new to Japan. I had no history with the place, no desire for it until I was knee-deep in debt and needed a way to earn money. English teaching was the answer, and what would bring me to her rooms in Tokyo, and to the shamisen.

Chi chi chi, ton, ten!

It was sweet, it was sour, it snapped, it slid.

She affixed it on my lap with sticky pads that looked like jar grips. She gave me a pick to travel its strings. She sat across from me and we played its tilting, melancholy notes.

“Wait! Space!” she called.

My fingernail split.

Shouldn’t there be another note, something to complete it, restore it to balance?

“No,” she said. There was nothing. Only ma, space, the “live blank” that existed between sounds.

“How can I learn?”

She looked at her hands, as if the answer lay there in flesh and bone.

“You have to steal,” she said. “It’s the only way.”

Her first lesson: no matter how much I was given, only the things that I took would be mine.

I found Sensei in the classified ads of an English magazine, under “Learning” or “Arts,” I can’t remember which, as she used both, depending which brought more students that week. Free lessons in shamisen and singing! Take something home with you from your stay in Japan! That it was so small and sandwiched between other ads made it no less extraordinary, the most radical word being “free.” This was usually reserved for old futons or space heaters. And the appearance of the word “shamisen,” appearing nowhere else in the hip contemporary magazine, was so unusual that it prompted a friend to cut it out and send it to me. She had circled the ad and written on a Post-It: “I thought you might want to check this out.”

So she remembered, I thought. The living room of our dorm at Smith College, in the fall of 1985, our freshman year. I was playing the grand piano in the living room, appreciating the fine keys and action. She was sitting on a sofa in wraparound shades, swinging her room keys around the tall neck of a Rolling Rock beer. On her feet were black canvas high top sneakers, spiking up from her skull was a prickly blond Mohawk. By the end of four years, she had a bob, an art history major, and a job teaching English in Japan. She’d married a Japanese and now worked in an art gallery.

“No matter what you see, it’s Japanese underneath,” she had told me over tempura on my first outing to Tokyo, where she pointed out that energy drinks contained nicotine, and a bottle of something pearly pink in the supermarket was squid poo.

But at times, she confessed her loneliness, like at a shrine festival that summer, when she gestured to the families in cotton kimono strolling past. “This is when you know you’ll never fit in.”

I couldn’t imagine making a life in such a stark, drab place, such a scrambled city, full of ugly buildings like the school where I worked in Odawara, made of cinderblock, with its plain classrooms where I could not even leave a pair of pumps overnight because of the rules.

Odawara was known for pickled plums, trick wooden boxes, and fish paste. From the veranda of our apartment, you could see its hills ringed in mist, the sparkling sea, the wing of a reconstructed castle roof. On the streets downtown, electricity ran over ground in thick cables trained up like wisteria. The sky was always inflamed, like a hot puffy sore.

I had come to Odawara with my boyfriend Larry, whom I’d met in graduate school in Chicago a few years before. Larry was Southern, soft-spoken, shy. In Japan he refused to bow. “It’s undemocratic,” he said. I wanted to know how deep to bow, and to whom. He had trouble folding his long lanky frame under lintels and tabletops, and struggled with his cowboy boots in genkan entryways. One boy in his class, Tetsu, pointed excitedly to his steel-tipped toes and said, “Dirty Harry.”

Two hours south and west of Tokyo, Odawara offered little to do aside from work. I planned outings to nearby temples and shrines, but sometimes it was just as fascinating walking to the stationery store, passing the train station where an old woman grilled skewers of meat on a charcoal hibachi and high school girls ringed their calves with glue to get the perfect slouch on their socks. At a gas station, eight men and women in green jumpsuits alighted on the entering car, as swiftly and intently as dragonflies, to fill its tank, wash its windows, check the tires, and refill fluids, all in one choreographed sweep, then lined up and bowed as the car sped away.

How to explain that these moments of mystery were here before Sensei, and that they only increased after, not to be solved but to be known in all their unknownness?

Larry was everything I could want in a life partner, and this wasn’t not on my mind. I was twenty-eight and had given myself until thirty-one to get married, thirty-three for my first child, though I had no idea where those numbers had come from. We were good friends, he was smart and liked to talk, he was trusting and gentle.

These were all good reasons but on the plane over I was already leaning into the window, writing in my journal that I didn’t want to be pressured into commitment by a “middle-class spinster specter.” I envied a girl in overalls sprawled across three seats, dozing. “I don’t know if I ever want to get married,” I wrote that first year in Japan.

In the corner of our bedroom sat two backpacks filling rapidly with travel guides, maps, and paperbacks for a trip to Thailand in December, when our teaching contract was up.

At night I wrote stories of invented languages, weird occurrences, a haunted apartment. And the strangest of all, a vision I had on the eve of leaving for Japan: a woman abroad wearing the high collar and long skirts of Victorian dress, sitting at a desk writing letters. She was a friend to the “natives” and spoke their language perfectly. She defended their cause and used her power to earn them equality and protection, to preserve their endangered culture.

I told no one of this vision. It was an Orientalist fantasy, a colonial embarrassment, this portrait of a woman who was utterly and capably alone.

The day I met Sensei the mugginess of summer was hanging on. By the time I reached the train in Odawara to take me to Tokyo, I was mopping sweat from my upper lip and wishing I hadn’t worn a white oxford. I watched the rice fields as we pulled out of the station and glimpsed Mount Fuji, which could appear suddenly, like a giant looking over your shoulder, but it was cloudy, only its peak transparent like a flat white crayon in the distance.

When I called to respond to her ad, Sensei had instructed me, in her heavily accented English, to transfer to a local train and get off at Setagaya Daita station, which I did, and which had none of the glamour or noise or festivities of even one station away. This Tokyo neighborhood was quiet, with a tofu seller and post office by the turnstiles, and an international grocery with coffee samples spicing the air.

Sensei stood in the foreground of all this, holding the bright green receiver of a pay phone. I had arrived late, and she was calling to see if I had forgotten, she told me later. The toes of her wooden clogs were tilted forward, whether for height (she was very tiny, maybe four foot eight) or as a way to rest her feet, I didn’t know. She was in full Japanese gear, which I later learned she donned for first meetings. They expected kimono, didn’t they? “Very Japanese-y,” she said and laughed.

Royal blue silk of a ro weave, so sheer you could see the white underrobe shimmer. A pattern of large flat fans and dolls. Small, well-defined hands. A thumb nearly not there.

And the hair: a thousand inky oiled strands combed into a sharp line at her neck. To call it a bob would be frivolous. This hair was rigid and composed. I admired its precision, its mystery. The vanity of it.

“I am—,” she said, and offered me her first name, Western-style. I used her first name, though I have always thought of her as Sensei, “the one who came before.”

The truth is I have never quite been able to find the right word for her presence in my life. Nothing seems to cover the enormity of her placement, her importance in all that came then and after. Mentor, monk, mother. She was none and all three. The best word she ever used came one evening at a restaurant where we were having dinner before a performance the next day. In the weeks leading up to a show, Sensei never used kitchen knives for fear of finger cuts.

We were picking at the scanty salad bar, feeling dreamy and expansive in the space between practice and the stage. We had a special relationship, she said. We were “comlets,”

Shooting stars? I thought. OK, sure.

And then I realized, of course, she had misplaced the “r” for “l.”

The word she meant was “comrades.”

At the station, she pointed down a small slope. A small purse looped around her wrist. I couldn’t help but think she was playing dress up, like a small girl in her mother’s closet. And I wouldn’t be exactly wrong. Something from the start about her rang out as grand performance and also absolutely true.

We walked along a busy road with four lanes of traffic roaring by in both directions. Bicycles rang their bells as they careened past. Her wooden shoes rasping the pavement, Sensei clipped along evenly, holding onto the side curtain of her hair in the gusts, squinting up at me, as if from a sandstorm.

Why was I in Japan? What were my plans? Why did I want to learn Japanese music?

This continued a line of inquiry begun on the telephone. She was serious about music, she had said. “We should enjoy.” Already it was attached to a philosophy.

It was hot. Everything was gray, the buildings, the sky, the people in their somber clothes. Only Sensei was colorful, like a butterfly in their midst. Whether it was true or not, as we walked the traffic softened a little, and the drabness of Tokyo was tempered by her friendship, her gentle but insistent presence at my side.

At a lone cherry tree, she turned left into what looked like a motel complex of three-story concrete buildings with long verandas. She had won her rooms in a government lottery, I would learn, after her divorce. I followed the drawl of her clogs up the stairs to the right.

“How often did you practice piano?” she asked as we arrived at door #105. She slid a key from her obi. (“To be a woman is to be always hiding something,” I read once.)

I looked at an empty ramen bowl sitting on a tray outside a neighbor’s door.

“A couple hours a day,” I said. I had always wanted to practice that long.

“Thinking and doing are not same,” she would say later whenever I was dreaming up some big thing I was going to do. Shake her head as to a small child. “Totally different.”

Inside it was dusky and felt like evening. She dropped her shoes and stepped up into the rooms, sighing, as if she’d just lugged a bag of heavy groceries up the stairs. She went around turning on overhead fluorescent lamps that cast a sickly glow. I heard the ticking of a gas flame as I unlaced my shoes and stepped up.

She came to the center of the room and clasped her hands as if to deliver dire news. “Shamisen music is disappearing and Japanese people do not care.”

Small talk did not seem to be part of her vocabulary.

I found her seriousness almost a performance in itself. There was an orchestrated quality about it all, and about her life, too. I didn’t know if she’d be young or old, married or single. I’d imagined, in fact, a blue-haired old lady with a husband snoring in the corner. But as she prepared our tea and moved us to more serious matters—music—she seemed entirely herself.

The apartment was three small rooms and a bathroom sealed off by an accordion door, above which hung, askew on its hook, a framed portrait of the Madonna and Child. The kitchen floor was brown linoleum, the walls, cracking concrete. It was old but clean. Polished, even. A small fold-out table on wheels held a black lacquer bowl that reminded me of her hair. Piled high were rice crackers in silky packages and bags of potato chips.

Instead of assembling at the table, she led us into the rooms, carrying two steaming cups on a tray. The room between the kitchen and music room was empty. The floors were smooth as a stage, and the sun was coming in off the back veranda, which opened onto an overgrown garden and the exhaust fan in the back of the family restaurant next door.

She paused at the threshold of the next room and let out a little puff of air. “My sanctuary.”

The doors between rooms had been removed and so it gave the impression of an approach, a region of delay, empty passage to buried treasure. For every corner and shelf of the room was filled with music. Scores, concert programs, photo albums, cassette tapes, CDs. Higher up were books, including the Edo Encyclopedia she referred to when teaching and photocopied drawings from to line our scores. Along the walls hung several shamisen, their sound boxes covered with silk pouches, some cut from the sleeve of an antique kimono. Tanned faces of drums lined the shelves, bamboo flutes perched in baskets.

I wouldn’t take it all in for years, when I would know what was in all the drawers, where to expect her to reach for a pencil or extra pick.

Two objects lay on the table under cotton towels. She whisked the towels away dramatically. “Say hello to shamisen.”

I was surprised at how unattractive the instrument looked, how odd. The smooth fretless neck was too long. The sound box was too square. Three tuning pegs stood out at the top like careless hairpins.

“Primitive,” Sensei said as I gazed.

“No, no,” I said, not wanting to insult it. Already the instrument had ears.

Why I expected anything, I don’t know. But the usual markers of beauty—symmetry, balance, a kind of smoothness or sameness—were not here. The instrument was not unlike Sensei herself, a beauty less natural than constructed.

She fluttered onto a stool, reached for the instrument by what appeared to be its throat, and settled it onto her lap. It took several attempts to get it where she wanted it. Playing the shamisen, I soon learned, was not about making it come to you. The shamisen was alive in this way, and required all kinds of careful tending. I wouldn’t guess this from looking at it. That day it looked like something easily tamed, a child’s toy. Primitive was exactly the word for it.

Then she began to prepare its fragile tuning, turning in small increments its ivory pegs and striking a string, back and forth, until it satisfied. “Would you like to hear a short piece?” she asked, and it seemed for a moment that it was she who was auditioning for lessons.

She played with her eyes to the floor, her hand moving up and down the neck, the sleeve of her kimono fluttering.

Music filled the room, sad and forceful and leaning, as a kind of breeze, colder here, warmer there, but without firm shape. Her pick slapped the skin, her left fingers pinched the strings, and sliding over the notes came her voice in a kind of pained bleating. She made quiet vocal cues when she wasn’t singing. She seemed less to be playing the instrument than having a conversation with it.

The sounds fell on my arms like a shawl, sometimes enclosing me, sometimes exposing me. But I was enveloped totally the whole time. If I had tried to stand during that two-minute interval, I don’t believe I could have. Something in the music pinned me down, jolted me awake, as if asking me a question.

Then she put a shamisen in my lap and did things that I assumed I should do, too. The more carefully I watched, the more carefully I did them.

On breaks, she brought more tea. How long would I stay in Japan? Were my weekends free? She told me about an American professor, one of few in the world who knew this music. Can you imagine? We can do many things.

I had so many questions—Where did they get the cat skins that covered the sound box? Why was the pick so heavy? Should my nail be splitting like that?—but they seemed childish and jittery in the sober atmosphere of the room, with its charged melancholy music. And I was thrilled to have a future implied, that we would be attached in some way, our destinies thrown together.

Mostly I didn’t want to disturb the feeling that with an instrument in my hands, I felt in control again, no longer without aim. There was hope.

The music itself was vexing, with the ma, and the hard-to-find notes, and the discomfort of merely holding the instrument in my lap. But it stirred my desire, which stirred my ambition.

And longing. I recognized the reverberant, sad, solitary sounds immediately as the same ones that followed me through the streets of Odawara. On these tours I felt solitary but not alone. All around me the Japanese people were sorting themselves into patterns and groups. Something unformed inside me rose up alongside them, like when playing piano as a girl the notes on the staff contained the promise of organizing myself into something useful.

To learn, Sensei said, “Narau yori nareru. Do you know this expression?”

I was quite peeved by then. To be struggling in front of her masterful strokes was humiliating. I’d never done anything I couldn’t do well right away. Which is probably why things never lasted long, or could hold my interest.

“Instead of learning, Janet, experience.”

As it neared noon, Sensei asked if I would like to share a “poor meal.” I accepted and followed her into the kitchen. This is how it was: she drifted and I followed. There at the little fold-out table on wheels she explained over bowls of rice and miso soup that the shamisen and voice played in two separate strands that were to never meet. It was the style of the music and it was hard to master. But separate they should stay.

She also laid out the anomaly that the shamisen had become in Japan, stray and unsounded, and in need of hands to play it.

“Do you know how much shamisen lesson cost? 10,000 yen, fifteen minute. How can you learn?”

Along these lines she continued as I perused the little plates she put before me. Rice and bamboo shoots. Miso soup with radish. A plate of pink pickles. I grazed and listened, nodding as she spoke in her unusual English. Unusual not in the way of the phrases I saw on tee shirts and shopping bags: Level up! Or, I want a dream with you! Sensei’s English was unusual in that it said so much with so little, like the shamisen itself: a few notes surrounded by nothing at all.

Brief, clipped, heavily accented, her words always remind me of fat brush strokes on an ink painting with lots of white space around to make them bolder, with the weight of truth. If she was fluent—and I cannot say that she was or was not; as on the shamisen I often wondered, how much did she know?—she was fluent in her own way. She found the words she needed to express what she wanted. And it was something quite urgent. They were the words of a drowning woman, you might say. Words set out like ropes to be taken up by the right people, the ones who understood and had a similar urgent need.

In the kitchen, Sensei put on a checkered smock with keys that jangled in the pocket and contained the sleeves of her kimono. She was as confident here as in the music room. Her kitchen music, I have come to think of it: the whoosh of the refrigerator door; the tick-tick of the gas flame; the kettle that never whistled, only rustled, like wind-blown leaves.

As we ate she shared a brief resume of her life. There was a husband who gambled and drank and stole, to whom she bore two daughters in the same year. Then she threw him out. When the girls were grown, she threw them out, too. “I need my own life,” she said.

It was these asides to the music that made me want to sit back, as if in a darkened theater, and watch.

She got up to cut a pear for dessert, fanning the slices on a gold-edged plate. When not speaking, she looked melancholy, and her brightness faded like the strum of a shamisen: a snap dissolving into sadness.

She returned to the table with the plate of fruit. “I want to expand shamisen music more.” She rolled a hand near her chest, as if drawing something out. “Foreigners love this music. They can learn. They have passion.” She plucked a pink pickle and popped it into her mouth.

How could she be so sure? I wondered. But it intrigued me that she’d thought long and hard about something and become entirely clear on the matter. At the time, there was little I didn’t doubt. I had been asking myself since leaving college—the last of the organized places I would exist, when I had music, too, organized on those staves, the notes in their places—what was I to do now? Ordinary life looked bleak and routine, and so I’d reacted with big international gestures.

“I don’t like Japanese way,” she said. “I think music is about spirit. You are musician. I can tell.”

“Not really, I mean, not professional or anything.”

She nodded and chewed for a moment.

“What is your purpose, Janet?”

She turned her inky eyes to me. They were very soft kind eyes, and this always surprised me within the framework of her severely cut hair. Inky and slick, like river stones.

As I began to reply with all the reasons why I was in Japan, something had already fallen away. I knew by then, as the sun rose overhead and noon passed—I had been there since early morning—by the way she used her words, by her urgency in teaching me the shamisen, by the kimono and the wild improbable cape of her hair, by the photo she took as I fumbled with a shamisen in my lap— “evidence,” she said, though of what I did not know—that this question was not what it seemed.

“I don’t want ordinary life,” she continued. “Watching TV, going out spend money, seeing friend. Genki …? ” she said, imitating the fetching mewl of young Japanese women. “Like your students. I need some purpose.”

“Paaaa-paaaase …, ” she said in her thick accent.

We were in something together now. She, me, and the music.

Things started spilling out of me. I laid them on her table along with the plates of pink pickles, waving my chopsticks over the miso bowl, putting my middle finger onto the second stick as I’d seen her do for an easier grip. I went from bowl to bowl, dish to dish, devouring.

I was from a small town, born of working parents who were not familiar with the arts. The exception to this was an aunt, my mother’s sister, who took me to concerts, plays, and poetry readings. She gifted me with sacks of books at Christmas, and dropped off videos of Maria Callas or an Ibsen play. We never spoke of them. Nor did my parents.

By her front door, my aunt kept a large sea shell, a footed conch, its pink belly facing up. “Hold it to your ear and you can hear the ocean,” she said. Growing up, I would take the hard spiky shell into my hands every time I entered. The mysterious sounds inside the shell excited me and seemed to echo some raw force I felt inside. Like placing my ear to Bach on the cassette player on Sunday mornings after church, I knew these sounds were not outside myself but were a part of me. There was an invisible world within, just at the edge of the visible world.

Sensei nodded knowingly. “Ehh … They can’t understand you.” She listened and I spoke, until her kimono and the salted salmon and the bamboo shoots fell away, and we were two women in a kitchen sharing secrets.

During our meal, Sensei asked, “Would you like to perform with us in three weeks? We need a singer.”

“What do you mean, perform?” I asked.

“Of course. Without performing, no meaning.”

My last performance, in a Junior Miss contest at sixteen, crept into my mind and I tried to push it away. Chopin’s “Minute Waltz,” the repeated refrains and then the bridge, where everything went blank. I’d gone on in the blankness, refusing to stop, striking keys as if knocking on doors to see what was behind them, until one finally opened and the rest of the song tumbled out. Even the trophy they gave me couldn’t erase the humiliation I felt.

Sensei dropped her slippers and slid wordlessly into the empty middle room, filling it quickly with garments she peeled out from long thin drawers in a chest against the wall. Kimono, a long white underrobe—“You need monster size,” she said—and a pair of white tabi like the ones she was wearing on her feet.

A whiff of aloeswood rose, bitter and sweet. The accumulation of garments was convincing. That she had such power, or a sense of it, drew me closer, and I latched onto the plan easily. If she thought I could, then I could. Saying things out loud, I was learning, was powerful.

“This works?” she asked, holding out a kimono.

I floated over to her and she began to fasten it around me, her tiny hands cinching and fastening. A handful of ties splashed to the floor. Order was not present, nor needed. Something else was at work now. I would learn about Sensei that in her life and her music, there was a companion to order and control, and a time when it should be taken as seriously: intuition.

She held out a split-toed sock. “Try tabi.”

I slid my foot inside the cool white cotton and wiggled my toes. It fit.