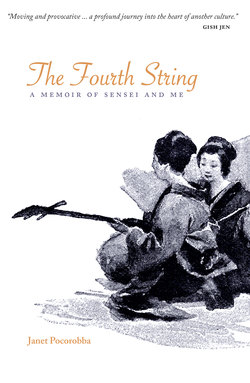

Читать книгу The Fourth String - Janet Pocorobba - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2 … less notes and rests than irregularities …

ОглавлениеSensei often said of her music, “We can never know truth.” Was Kurokami written in 1842? 1840? Was the empty space one beat, or two? Hers was an oral art, transferred person-to-person slowly over time, and even when the music was finally written down, in the late nineteenth century, one could never be sure. This didn’t mean Sensei didn’t believe in facts. She just believed knowledge of any kind was better in small doses for the same reason emotions were better kept under wraps: knowledge—like feeling—was powerful, and once acquired, it was impossible to turn back.

Her own facts appeared in fragments at lessons or at the kitchen table—the shadow of a maple leaf on the papered doors of her mother’s den; the hairstyles of old women in the town she grew up in—each detail enlarging or shifting with metaphoric resonance. It may be I who enlarge, shift, diminish. Our art, and our relationship, is written only now, in an effort to pin down, cohere, make a narrative of all the broken bits, seal once and for all, the empty space of ma.

I remember every performance with Sensei, every venue, every stage, even now after twenty years. But how to pinpoint what I learned? It is this that fails me, that lures me into floating in definition. Was it at that first lesson that she told me geisha trained by singing outside in winter to break their voices? That her eldest daughter was a fortune teller? That using the very tip of the finger was best, not the fleshy pad? Her lessons were more like listenings. She seemed less to be teaching me than stirring me round and round, as if distilling me into some ancient wine. The performances were the shape of our days, our years together, but what truly formed us had no time or location or date.

Sensei, if my calculations are right, began her new life teaching foreigners in music at the age of forty-eight. When I met her I think she was fifty-two. She was secretive about her age, like her hair color. If she was forty-eight, it would have been her zodiacal year, the year of the rooster. A preening bird possessive of its hens. It is not an auspicious time. When it is your year, you must be on alert and careful in everything you do or say, so as not to offend the gods.

That year Sensei gave up studying Russian for English.

“Those wars are so passé,” said her eldest daughter, the fortune teller I’d once spied in a green kimono hurrying to the station at dusk. “Probably Shinjuku Station tonight,” Sensei said, nodding.

Sensei began attending English lessons after work at Trendy House, an English school tucked away in a bank of shops near Shibuya Station. By the time I met her, the school was embroiled in scandal. Embezzling, cooked books, illicit affairs. Sensei’s youngest daughter, a graphic designer, would soon produce an acerbic mockumentary about the school called “Let’s Do Talk.” She wanted Sensei to play the role of the class nerd who keeps calling people out on stuff, the sole moral compass in a sea of vice.

I’m not surprised Sensei hated the classes filled with businessmen, office ladies, and housewives. To abide the mundane dialogues, like the ones I taught in class, must have been a kind of torture on her ears. I can see the sullen lips, the slightly rising chin, the dark boil. It’s not that she wasn’t humble. In all the time I knew her, Sensei worked at a hospital sterilizing instruments for surgery, a job perhaps only a step above making tea for executives. I tried to picture her in scrubs and long yellow gloves at a basin of shiny steel scalpels. She kept a long pair of bandage shears in a drawer in the music room, her “revenge” dagger, she joked, for students who didn’t practice. She would never think of leaving her day job. To her, it was security for her life in music.

Soon she engaged a private teacher from Australia, Jacqueline. Through Jacqueline she learned that foreigners wanted to know more about “the real Japan.” They sought out old things they could touch and feel and take home with them. What space opened in Sensei hearing this? What new thoughts? What new way of being amid direct words, broad gestures, laughter, freshness?

Was it plan or coincidence that she had a shamisen with her one day at a lesson? She would have settled it on Jacqueline’s lap at the thirty-degree angle, placed the heavy oak pick in her hand, and showed her the protective strike zone on the cat skin below. She would have called out numbers and corrected her for ma, the little sips of silence between the notes. Showed her how to use hitosashiyubi, “the pointing-at-other-people finger,” sliding it along the strings until the nail split and a small callous began to form on its tip.

Jacqueline came to her house on weekends for lessons. Sensei did not believe in charging money for something that should be about “pure spirit,” so her lessons were free. The day job, giving free lessons to foreigners—this was how she kept herself apart from the traditional world and is part of the complicated legacy from which she comes.

Sensei left her hometown of Toyama City at eighteen and never looked back. Her mother’s family had considerable wealth but lost everything in the fire bombings, which destroyed the whole city. Her mother was a dancer in the Nishikawa guild who, at twenty-three, had met Sensei’s father, a besotted sixteen-year-old who helped with her performances.

“Terrible match,” Sensei said. Her father became a high school principal. Her mother kept dancing.

Sensei was born at the end of the war. Her given name meant “sincerity” and was a man’s name in Japan, but I’ve been told that after Japan’s defeat, in the postwar democracy, under an American constitution, it was a popular name to maintain the old Japanese spirit as the nation entered a new age.

The traditional arts must have felt unfashionable to a young woman growing up in the 1950s. Dance with her mother, an incursion on her own dreams. She went out after school with boys, smoking cigarettes in her kimono. I can imagine the erotic allure of that. She loved Pat Boone, long walks in the mountains, and when she was eighteen, she went to Tokyo to find her own music.

Being from Toyama, a small city on the Sea of Japan, she must have felt like a hick. She stayed with her sister and brother-in-law until her mother could find her a teacher at the Fine Arts University. She was looking for a teacher of nagauta, the “long songs” of her own dances. There was no other choice. One didn’t dabble or explore freely. Music was taught, like long plaits of hair, in direct lineages, passed on in guilds by powerful patriarchs.

I suspect that Sensei already played the shamisen, that her mother taught her so she could play for her dance students. If so, she knew this music, its tempos: less notes and rests than irregularities, like sound and its interruption. Beforeness and afterness.

Finding Kikuoka-sensei changed her world forever and set her apart, as he himself did, and gave her a model for going it alone, for being a maverick. Though their musical lives couldn’t have been more different, inside, I think, it gave her strength, this identification with his spirit.

Kikuoka-sensei was handsome, silver-haired, fatherly, with a big smile. On stage, he sat in the center of the long back row, as unmoving as a potted plant, his skill visible only in his surefooted strumming, and an almost supernatural sense of the singer’s timing beside him. As he played the shamisen, he entered the music so fully that he seemed to have disappeared, fusing with the three strings, the long heavy neck. The effect of this on me whenever I saw him play was vivid. Sensei’s teacher’s playing always made me feel, if not that I could play quite like that, that it was worth doing.

His idea was to build a musical group based on skill and merit and not patronage of musical heads of state. Players would use their own names, be listed in the program as themselves instead of following custom and taking on the patriarch’s last name. The group was called To-on-kai, short for Tokyo Ongaku Kai, the Tokyo Music Society. Every season their small quarterly program, a robin’s egg blue with simple black characters, appeared clipped to Sensei’s calendar.

“You don’t have the heart for this,” Kikuoka-sensei told her one day and advised her to remain an amateur. I wonder if he saw how she darkened at the slights and barbs of competing students, how she complained of unfairness, her hurt and anger. If he saw that and wanted to save her the heartache, and save the music for her, too.

During the difficult years after her divorce, he waived her lesson fees and let her barter for work in the house with his wife, a retired dancer. She stirred the kinton, chewy chestnut sweet, over the stove for days at New Year’s and massaged his wife’s shoulders. She sold tickets to his concerts. When she asked how she could pay him back, he told her, “Teach.”

But here was the interruption. Unable to take his name in the usual way of family clans, nor wanting to enter the professional world she couldn’t bear to join, she was alone with her music.

Her marriage did not define her, nor her daughters, nor her mother. She would go on until she found Jacqueline. After Jacqueline there was Gerry, a Canadian, who left her to learn folk music. Every year, during cherry blossom season, when the petals were lining the streets of Tokyo like pink frosting, Sensei would turn to the window. “Gerry must be near Sendai now,” where the northern cherries were in bloom and there was money to be made busking.

It was Gerry who found the American professor’s papers. Sensei wrote a letter, telling the professor of her idea to teach foreigners. She did not charge because music should be free. She would shame the Japanese, into doing what or how, I never learned.

“Why not teach Japanese?” I asked her that first day. “That way they can pass it on.”

She stared at me as if I were a small child. “Complicated,” she said. “You will see.” Something went dark when she said this, and the atmosphere changed, like we were in one of those snow globes, enclosed in something you can never get out of.

Then she brightened. “Anyway, we should enjoy.” She raised her chin and sipped her tea, folding the edge of her bob at her jawline.

I later found out she’d been born with waves. It was a rainy day and we were in formal attire, heading to a concert, and she was panicking about the weather. She ran back into her rooms and emerged wearing a green silk scarf tied on her head, and when I asked, she admitted that her hair was wavy. She seemed relieved to have caught it in time, to prevent what was natural from coming out, keeping the waves straight and drawn evenly to an icy line at her neck.