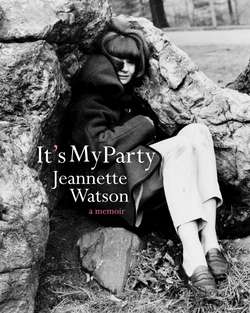

Читать книгу It's My Party - Jeannette Watson - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter One

I have always loved to laugh: a loud, raucous belly laugh, which, I regret to say, often ends in a snort. My father felt my laugh was unfeminine. He used to say, “With a laugh like that you’ll never find a husband!” Years later I would tease him, saying, “I was able to find not just one, but two, in spite of my laugh.” Actually, my first husband hated my laugh, but so far—thirty-seven years—Alex, my second husband, doesn’t seem to mind it.

My parents’ first baby, Thomas J. Watson III, died as a baby, just before Christmas in 1942. I can imagine how devastating it must have been for a young couple to lose their first child. The baby died without warning, of no known cause. Their second son, my brother Tom, arrived two years later. (I would later think it quite weird that they gave the second baby the same dynastic name as the first, as though the first baby hadn’t existed.) I was born sixteen months after that, on October 9, 1945, and then came Olive, Lucinda, Susan, and Helen. The first four of us were bunched within six years of each other, with the last two girls born in the next six. My parents had hoped for another boy but gave up after five girls.

Taking care of six children was quite an undertaking, especially because my mother was also a corporate wife who had to travel and attend business functions with my father. A baby nurse cared for us in our first six months, before we graduated to the care of a governess. When I was about three, my parents decided an English governess would be just the ticket for us, and off to London they went to find “the perfect nanny.” My mother spent the morning at an agency interviewing candidates. She narrowed them down to two. She told my father that one was pretty, and one had dyed red hair and bad breath. My father told her to hire the second one, on the theory that she would never marry and could devote her life to raising us.

Olive with Tom and six-month-old Jeannette

Jeannette looking pensive at age one

Nana, or “Nanner” as we children called her, did not have an easy life with us in Connecticut. Back then nannies were on call twenty-four hours a day and were only off on Thursdays and Sunday afternoons. Nana had a small room where she kept her meager life possessions and her African violets. On prominent display was a photo of the previous child she had cared for, the saintly Nicholas. She always referred to him as her dee-ee-ar Nicholas. We, sadly, were neither saintly nor dear. My mother often countermanded Nana’s edicts, undercutting her authority and implicitly condoning disrespectful behavior from us. I often felt extremely guilty at my rudeness when I saw Nana go weeping to her room. She stayed with our family for almost ten years. None of us kept in touch with her after she left. I knew other children had very close relationships with their nannies, and my husband, Alex, adored Joannie, his nanny, but I don’t recall any affection between Nanner and me.

Lucinda, Jeannette, and Olive in the “pram”

Nana brought a British vocabulary with her that became our own. A washcloth was a “flannel.” “Woolies” were the horrible pink long underwear we girls were forced to wear over our underpants. (They were made of scratchy wool and came down almost to our knees. We all hated them and lived in terror that a classmate at school might see them.) A “windy-pop” was a somewhat endearing name for a fart. When one of us misbehaved, which was often, she would say, “Beg [pronounced baaaaayg] pardon,” as if she were speaking to an errant dog.

Nana took a special interest in our bowels. Clockwork regularity was the goal, and every Thursday afternoon we had little glasses of prune juice. Her term for a bowel movement was “big job,” and when we went to the bathroom, Nana asked, “Big job or little job?” I remember she made us all sit on different toilets every morning to do our business, and when we finished, we would give the assigned signal from our various command posts: “Nanner—I’m all readyyyy.” After her inspection we were allowed to leave the toilets.

The pony cart we used to collect blackberries

When we first moved to Meadowcroft Lane in Greenwich, it was quite bucolic. There was still a lot of open land and even some working farms. We had lived in two other houses in Greenwich prior to Meadowcroft, but I was too young to remember them. The end of the lane was filled with blackberry bushes, and we had a little pony that would pull us in a cart so that we could go exploring and collect blackberries.

Every day Nana would lead us on a long walk, pushing the latest baby in a carriage, which she called the “pram.” We would walk from Meadowcroft Lane, turn right on Greyhampton Lane, go down the hill to Lake Avenue, and then make a left toward the green bench (called “the form” by Nana), where we would gaze at the herd of cows that have long since been displaced by houses. After a brief rest on the form we would march home.

With so many children around, something was always happening to one of us—falls, concussions, sprains, and scrapes were commonplace. We also seemed to injure each other during unsupervised “play.” My parents felt that we had to deal with our own battles and did not encourage us to tattle. Luckily during active warfare I could run faster than some of them and would race upstairs and lock myself in my bathroom and read the books I kept there. We had strong feelings about each other, sometimes verging on the murderous, but pencil stabbings were as close as we came to sororicide. Sometimes I prayed that some of my siblings would be painlessly and miraculously removed from the family. After praying for this ardently for several months I gradually lost my faith, but I dutifully recited our scary nighttime prayer:

Now I lay me down to sleep

I pray the lord my soul to keep

If I should die before I wake

I pray the lord my soul to take

Sleep and death became intertwined, causing nightmares.

Our house was a fairly conventional white-washed brick. The brick color came through the paint, giving it a slightly pink hue. The front door opened onto a spacious entryway. To the left a gracious curving stairway led to the second floor. In a niche under the staircase stood a table where the mail and magazines were placed. There was a third floor, not visible from the first floor. The main residence eventually had eight bedrooms: one for my parents, one for the nanny, and one for each child. As new babies arrived we were shuffled around. Eventually Olive and I, as the two oldest girls, moved to the third floor. At first we slept in one large room, where my numerous dolls lived in their own tiny room in a corner. I had a Ginger Doll with her own trunk filled with beautiful clothes. Another doll came with a lovely canopied bed. I remember a Betsy Wetsy, to whom I fed water, causing her to wet her diaper, which I changed. I must have had at least thirty dolls: baby dolls and dolls appearing to be anywhere from four to ten years old, all different sizes. This was before the age of Barbie, so I didn’t have any sexy teenage dolls. My dolls were beautiful and would be collector’s items now. I spent hours caring for them.

Olive and I used to discuss which bed in our room was safer. I slept next to the door and felt a robber would get me first. Olive said a ghost coming out of the closet would get to her before it got to me. Later on, my parents felt we should each have our own rooms, so two bedrooms were created, with a large bathroom. I was happy to have my own room, where I could disappear and read, and a bathroom door that I could lock in case I was in need of a retreat from a battle with one of my siblings. I always kept the bathroom supplied with books, though I can’t remember where I got them all. I do know that in the early days we went to the library, and later on I think I just read whatever I found around the house—often Reader’s Digest condensed novels.

There were enormous attics off our hallway, one of which was filled with my brother’s elaborate electric train set. Another was used to hang some of my mother’s dresses. I remember in particular a bright-red flamenco dancer’s dress edged in white lace with a black-fringed shawl. In later years it was joined by a strapless floral ball gown with a note attached, in my mother’s handwriting: “Worn at the White House dinner seated next to Jack Kennedy.” My sister Olive said she also saw the dress my mother wore when she was Peanut Queen at some festival long ago: It was a form-fitting V-neck long dress covered entirely with peanut shells. My deb party dresses joined my mother’s dresses in the long attic.

Downstairs, branching off and to the right of the front hall, carpeted wall-to-wall in pale green, was the wood-paneled library, where we would welcome my father when he returned from work, usually around 6:30. “Get down to the library!” Mummy would command. “Your father is coming home!” He arrived like a general intent on conducting a full-dress review of his regiment. As he wrote in his autobiography, “I often ended up carrying my frustrations home with me, where my wife and children would bear the brunt. Olive would spend the entire day working with them, and she’d have them all shined up and ready to greet me when I came home. I’d come in the door and say, ‘That child’s sock isn’t pulled up. That child’s hair isn’t combed. What are these boxes doing in the hall? They should have been mailed.’ It was the same demanding IBM attitude, and it was very hard on them all.”

The library was also the place where we were summoned for scoldings if we had misbehaved or fallen short at school. These “Library Lectures” could be quite stern, even harsh, and some of the things my father said left permanent bruises. Fortunately, I mostly managed to stay off the radar. I rarely did anything good, but I rarely did anything bad either.

Just off the library was a formal living room that we never used. Its furniture was dark, and its sofas were stiff and uncomfortable. Beyond the living room was a screened-in porch. This porch became known as the “poor room,” as my two younger sisters wanted a place where they could entertain their friends in a more casual way, without being embarrassed by the “rich” look of the rest of the house.

To the left of the front hall stood the very austere formal dining room, with dark polished wood floors under an oriental rug. The room was dominated by a large mahogany table, which could be made even bigger with the insertion of more leaves. On the sideboard the obligatory silver tea service reigned in stately splendor alongside a black lacquered Chinese screen.

The dining room led into the less formal “breakfast room,” where we sat at a round table featuring a lazy Susan designed by my father to efficiently pass the sugar, cereal, butter, and jam. During the week we had a quick breakfast—I usually ate Grape Nuts with bacon crumbled on top. But weekends were different: eggs on Saturday and waffles Sunday.

The breakfast room was just off the pantry, with its glass-door cabinets filled with Steuben glass and sets of china. Adjacent to the pantry was a large kitchen with a double sink and several ovens. The “help” had a small sitting room off the kitchen with a sofa and two chairs for watching TV. A narrow staircase led up to the “servants’ wing,” which had two bathrooms and four small bedrooms: for the autocratic Russian cook Willie and his German, stereotypically-Nazi-like wife Mary, who was our housekeeper and waitress, and for Hannelori, Mary’s pretty, somewhat sexy, buxom young German assistant. Hannelori wore form-fitting uniforms, unbuttoned one button lower than usual, and large fake dangly diamond earrings. She created quite a sensation, in general. We were rarely allowed in this part of the house because Willie and Mary disliked children. Nanner slept upstairs in a room between my two younger sisters. A laundress came several days a week to labor in the Stygian inferno of our large, dark basement, and on Thursdays, which was the cook’s and nannie’s night off, a lovely Irish woman named Margaret came to take care of us. On those nights we were allowed to make our own delicious sandwiches—Skippy peanut butter and Smucker’s raspberry jam on Wonder Bread. I had eggnog with my supper (no alcohol!), which I mixed up in the blender.

After Margaret had sandwiches with us, my mother cooked dinner for my father. I remember thinking how dull his dinner was: a hamburger and baked potato, with frozen vegetables, served to him by my mother on a tray in the library.

We had what in the ’50s might have been considered a large house (though not unusually so for Greenwich). Two years ago I took my son Matthew to see the place where I grew up. I was horrified to see that Meadowcroft Lane is now chock-a-block with McMansions three and four times bigger than my old house and built on plots significantly smaller. My sister Susan recently sent me a Sotheby’s description with photos of our house, which was for sale. It had practically doubled in size, with elaborate servants’ quarters. I could scarcely recognize it.

We lived on about seven acres of land perched on a hill above a lake. Along the hill were flower beds, where a full-time gardener seemed to plant mainly roses. A small ornamental pond filled with goldfish sat nestled in a group of trees, with a large open fire pit nearby for barbecues.

Our lake was a source of great pleasure. Several majestic weeping willow trees sheltered our small dock. We had a canoe that we loved taking out on the water. A strip of land separated our lake from another one that had two small islands. We could drag the canoe across to explore the other lake and its little islands.

In the winter the lake froze over, and gliding over its black ice was the best time I ever had on skates. Sometimes my parents had cookouts by the lake, with hamburgers and hot cocoa to warm us up. When I was four and my brother six we were wandering unattended by the lake. He told me to avoid a place where the ice was thin, a warning that I blithely ignored. The ice broke, and suddenly I was in the cold dark water. Luckily for me, my brother was able to pull me out, and we went back home. I remember my mother taking off all my wet clothes in the kitchen (much to my humiliation) and then marching me upstairs to a warm bath. No one seemed too concerned: perhaps because there were so many of us!

In warm weather we roamed around the neighborhood without supervision. We each had our own “fort”—some hidden spot under a tree or behind a bush that was filled with “ammunition” (stones with which to attack our other siblings). After tiring of our own property, we explored old graveyards and vast estates. Local kids would gather at our house and we girls would play jump rope for hours, chanting:

Down in the meadows where the green grass grows

There sits (some girl) pretty as a rose

Along came (some boy) and kissed her on the nose

How many kisses did she receive?

Then we counted, the rope accelerating as the numbers rose, until the jumper missed a beat. We also played hopscotch, enacted scenes as Roy Rogers and Dale Evans, and invented dances. On rainy days we played jacks, pick-up sticks, and built houses out of playing cards. How innocent it all seems.

Our father gave Olive and me a little electric car that we shared—on the back it said “Jeannette odd days, Olive even days,” so we wouldn’t fight. Later on, we started skateboarding and used to drive to a nearby deserted house, a replica of Le Petit Trianon, whose long, sloping driveway was perfect for our new sport.

We had a little red playhouse with a real kitchen, where I would bake “answer cakes” (named after the mix it came in), which I embellished with chocolate frosting from a can. Sometimes we spent the night there. A tennis court stretched out beyond the playhouse, but we rarely used it.

We always seemed to have a large number of pets, and my parents were quite tolerant of them. The first pet I remember was Sambo, a huge Newfoundland. He was the sweetest dog and uncomplainingly let us ride on his back or do anything else we wanted. We all adored him, although I think our parents were vexed by the havoc he caused. Anytime a door in the house was left open, he would happily bound through the screen, totally destroying it.

Around this time, my grandmother Watson gave me a cat that I called Little Nipper—for obvious reasons. The two pets became inseparable: Nipper curled up next to Sambo, serving as a tiny pillow. When Nipper was injured and later put down, Sambo was inconsolable. In those days, if anything was wrong with a pet it was usually euthanized. There were no elaborate (and expensive) surgeries, medications, or acupuncture treatments. Later on I got a Mexican Chihuahua called Mitzy, whom I trained to sit, shake hands, and walk on her hind legs. I often dressed her up in doll clothes.

We had two golden retrievers: Punch, who belonged to Tom, and Mark, who became Olive’s. Punch was wonderfully gentle, and I loved him. Lucinda had a basset hound named Maynard, and of course various gerbils and goldfish came and went.

When one of the dogs killed a mother rabbit, I raised the babies in my room, nestling them in a cardboard box and feeding them from a tiny eyedropper. We later released them in hopes they would find some relatives on our property.

I often think of the food from my childhood. It was classic ’50s fare. I remember the soft comforting taste of Pablum, warm and sweet, and red Jell-O, which had a slippery consistency but no taste. I especially liked tapioca, a light dessert that was white and creamy with little chewy spots. We always added a spoonful of strawberry jam to white junket, smooth and soft. Custard was another bland, creamy favorite.

I grew up at a time when frozen food was becoming popular. How I loved Birds Eye beef pie, which was sometimes served on Sunday nights, when the cook was off. On Fridays we ate hamburgers and French fries with buttery Birds Eye frozen corn. We also enjoyed TV dinners, with each item confined to its own little compartment.

My parents worried a lot over bad breath and were constantly blaming garlic as the main cause of it—also raw onions, which I quite liked. At one point my mother said sweetly to me, “I hope you don’t mind my telling you this, but your breath is fetid.” When she saw my face fall she said, “Oh, do you mind my telling you? I’m always thrilled when your father tells me.” (I would imagine the conversation. My father: “Olive, your breath is fetid!” My mother, gratefully: “Oh Tom, thank you so much for telling me!”)

Because of their strong feelings about garlic, our meals were quite bland. Our father did make a delicious spaghetti sauce (without garlic) a few times a year, usually when we were in our home in Vermont. He enjoyed shopping for his ingredients and creating his sauce.

As children, the six of us were reluctant to try anything new. One night we were served apple Brown Betty with hard sauce, which we initially refused to taste. Our father insisted, and ultimately we all liked it.

We also protested when my father had the cook switch from butter to margarine, on his doctor’s recommendation. Daddy asserted that we couldn’t tell the difference and had us wear a blindfold as he gave us the test: toast with butter or toast with margarine? Olive could always tell immediately.

When we were little, we ate in the “children’s dining room.” One by one, as each of us turned eight, we moved to the “grown-up dining room,” where the atmosphere was much more formal and good manners were required (sitting up straight, not speaking with one’s mouth full, etc.). Often my father, still be in executive mode from work, spent dinner interrogating my mother:

“Olive, have you written that thank-you note to the Thornes?” he said strictly.

“Oh Tom,” (hand raised to mouth, eyes wide) she said abjectly. “I’m so sorry, I forgot.”

“How could you forget? We discussed it this morning!” he would snap.

Sometimes I wondered if she “forgot” on purpose, because this happened so often. It was like watching Martha and George go at it in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? The sharp volleys of my parents’ conversation could be quite exciting, but mostly they were gut-wrenching, especially when my father lost his temper. “The kids would scatter like quail,” he wrote, “and Olive would catch the brunt of my frustration.” Sometimes she would run upstairs and he would run after her.

My mother, a former model, was concerned about our looks and particularly our weight. Being “attractive” was very important to both my parents. At one point Daddy remarked on our “porkiness.” We were very devoted to our cook Willie’s chocolate chip cookies, especially warm from the oven. My parents decided this was contributing to the problem, so they kept the cookies locked up. When we sought them out, Willie’s wife Mary would say, in her guttural, harshly-accented voice, “No, you may not haff cookies—your mother says you are too fat.”

The emphasis on whether people were attractive bothered me. My mother sometimes passed the time playing the “Attractive Game.” She’d point to two people and ask who was the most attractive. I naturally played along, but not happily, because I was so insecure about my own looks. I have struggled my whole life to shake the impulse to judge people by their looks. I’ll be sitting in the subway and I’ll think to myself, “Oh, that woman is so fat.” Then I say to myself, “Don’t look at her that way, look how she’s holding her child, think something nice about her.” It’s gotten to the point that I hate the word “attractive.”

After dinner, if I wasn’t too porky, I would sit in front of the TV alongside some of my siblings with warm chocolate chip cookies and a glass of cold milk, gazing at my crush Edd “Kookie” Byrnes as he combed his pompadour on 77 Sunset Strip, or else admiring the beautiful Gardner McKay in Adventures in Paradise. Years later I was thrilled to become friends with Nick Dunne, the best-selling author who’d produced the show. Someday I’ll have to watch it again and see if it has retained its old allure. I’m sure Gardner McKay will be as gorgeous as ever.

Watching television was a great treat because my father considered it “the instrument of the devil.” I remember as a little girl thinking the people inside the TV could see me, and being embarrassed if I had my bathrobe on. When I was around five, my father somehow arranged for Tom and me to appear in the peanut gallery of The Howdy Doody Show. I remember Buffalo Bob yelling at the rowdy children, then instantly adopting his affable TV persona when the cameras rolled.

My father, mother, and four kids (from left, Olive, me, Tom, and Lucinda) in one of my father’s antique cars

On Sundays we all went to church—first to the simple white Congregational Church on Round Hill Road, which I loved, and later to the more social and formal Episcopal Church, which I felt no connection to. After church we would come home and eat a served lunch in our Sunday clothes. We would have roast beef or lamb, gravy, roast potatoes, and frozen green beans or peas or corn. For dessert, there was always a special treat for the children, like ice cream with chocolate sauce.

On Sunday afternoons we would go on long family bike rides up and down the steep hills of Greenwich. I lived in terror that someone from my school, Greenwich Country Day, would see me doing something so dorky as riding bikes with my family. Now I think it was sweet that my parents wanted to spend so much time with us.

If we weren’t bike-riding, Daddy might take us on a drive to see friends. I remember visiting Sam Pryor, former head of Pan Am. He had a huge collection of dolls from all over the world, and even asked his friends Gene Tunney and Charles Lindbergh to look for interesting dolls on their travels. The collection eventually grew to eight thousand dolls—the most valuable doll collection in the world. We also visited James Melton, who, like my father, was an antique-car enthusiast with a large collection. He was extremely handsome, and I had something of a crush on him. A popular singer in the ’20s and ’30s, he made his Metropolitan Opera debut as Tamino in Mozart’s The Magic Flute. Winthrop Rockefeller later bought most of his car collection, and some of it ended up in a museum in Seal Cove, Maine.

The first Palawan off the Maine coast

My mother used to take us to Tod’s Point to swim and have a picnic on the beach. We had yummy sandwiches and hard-boiled eggs, usually followed by green grapes, and, if we were lucky, those sinful chocolate chip cookies.

Our salads were made with iceberg lettuce—the only kind of lettuce I knew. Years later, after my divorce and my move back to New York City, I rented a house in East Hampton with a friend who was a wonderful cook. We drove to the Green Thumb to buy our vegetables, and my job was to get the salad ingredients. When I returned triumphantly with the iceberg lettuce she was horrified, and opened my eyes to other possibilities. My mother served iceberg lettuce at her cookouts until she died. My husband, Alex, who loves iceberg lettuce, was always grateful.

In the summer, we went cruising off Maine in my father’s fifty-one-foot sloop, Palawan.. We stopped frequently at the islands that dot the coast. To cook hamburgers, we’d often place our patties on stones heated in a wood fire. We loved exploring these rocky islands and picking wild blueberries—and also bringing back messy bouquets of wild flowers for my mother. As it grew dark my father and other grownups would tell spine-tingling ghost stories by the flickering fire—stories that sometimes gave us nightmares. Sometimes, my father would create a path out of pieces of a torn-up newspaper, a “paper chase” leading to a pile of candies.

Jeannette at sea, with Mary Poppins and donuts

I gladly participated in all of these activities, but my happiest hours were spent reading. When I wasn’t immersed in a book, I often felt sad, lonely, and inadequate. All of my siblings seemed more at ease, more athletic, and more popular than I was. I felt I couldn’t share my feelings with my parents, as they thought if I wasn’t happy it was my own fault. I guess I was experiencing the first signs of the depression that would plague me for so much of my life, but I had no way of knowing that at the time. Books transported me to sunnier places and became an addiction as powerful as alcohol or drugs. Marcel Proust said, “There are perhaps no days of our childhood we lived so fully as those we spent with a favorite book.” This was especially true for me. I vastly preferred the world of my books to the life I was living.