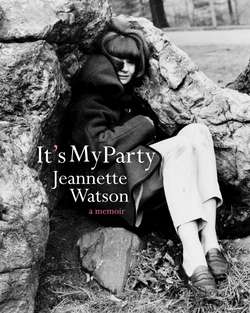

Читать книгу It's My Party - Jeannette Watson - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Three

My father was a mythic figure, blessed by the gods in so many ways. He was charismatic, smart, funny, and devoted to his family. He was a seasoned pilot, a renowned sailor, Mr. Twinkle Toes on the dance floor, a skier, a diplomat, an occasional chef, and, of course, head of one of the largest companies in America. He was like a Shakespearean hero with a fatal flaw. The real tragedy was that he knew it and was unable to change. As he wrote in his 1990 autobiography, Father, Son & Co.: My Life at IBM and Beyond, co-authored with Peter Petre, “If my disposition had been easier, I might have had a brilliant career as a father, because I did a lot of imaginative things for my children.”

Even today, twenty-five years after my father published his autobiography, and twenty-two years after his death, when I see his face smiling benignly out at me from the cover, I feel a stab of fear. Other emotions follow—love, respect, and gratitude—more in keeping with our public image. I have struggled to come to terms with my childhood, which was quite different from the way it appears in family photos, and with the haunting parallels between my father’s childhood and my own. We experienced similar feelings of alienation, depression, and sibling rivalry, and he loved and feared his father just as I loved and feared him.

His temper got the better of him, leaving wounds that occasionally flare up even today. I still am extremely uncomfortable with conflict of any kind and loud voices. Until fairly recently, I remembered Christmas mainly as the time of year when my father became inconsolably depressed, triggering the same emotion in me. The memory of how my parents sparred at the dining room table still causes my stomach to clench.

When my father was thirteen, he “began to suffer recurring depressions so deep that no one knew where they were going to lead.” He had to be urged to eat and bathe. He couldn’t read a book. He would recover after about thirty days, but after six months he would fall into the abyss again. “I’d slip from…thinking I was going crazy, to a stage where I didn’t know what was going on around me.” He also had suicidal thoughts, telling his brother Arthur, known as Dick, that “if I die, be sure to tell Mother and Dad that it’s not their fault.”

In Greenwich, Daddy seemed to revert to the kind of depression that he experienced as a teenager. The blues came like clockwork at Christmas. He locked himself in his dressing room, which had a bed and TV, as well as clothes closets and a bath, and my mother would beg him to come out. This happened occasionally at other times of the year, too. “When I couldn’t bend my wife and children to my will, I’d feel totally thwarted and boxed in,” he wrote. “…The only thing I could do was hole up.” Sometimes my mother would call his brother Dick in New Canaan, and he would drive down and “draw me back into my world.”

The tense relationship between my father and grandfather continued until grandfather died, in 1956, when I was eleven. My father said that they’d get into “hellacious” fights nearly every month. “They were savage, primal, and unstoppable,” he wrote. “When he criticized me, I found it impossible to hold back my rage.”

I never remember my father sitting down and reading during the day. Daddy was a dervish of activity, always eager to try something new, the more dangerous the better. A psychiatrist would probably peg him as a manic-depressive who used frenetic activity to prolong his “up” periods and keep his demons at bay.

He learned to fly as a teenager and continued to do so all through college. At eighteen, with his old friend Bill Pattison, he flew to Dallas to a deb party and then on to St. Louis. Before their first sortie, neither had ever flown at night. One said to the other, “I think we just turn on the lights.” They were the original young invincibles.

I began flying with him when I was small, and kept going aloft with him as his planes got larger and more sophisticated. He built a landing strip on our property in North Haven and often created quite a stir when coming in for a landing. We’d hear crackling on the radio, and then he would announce himself. “This is N6789er, N6789er. Do you copy Oak Hill? Susan, get your goddamn donkeys off the runway.” Susan would hop on her motorcycle barefoot and round up her wayward pets.

He got his jet license at age sixty-five (the oldest person ever to do so), and then learned to fly a helicopter. Whenever my husband Alex and I arrived at our house in the family compound, my father would hover outside our barn in his helicopter and peek into our huge glass window, wearing big goggles, with his white hair blowing wildly in the wind, giving him a slightly demented look.

He took up ballooning his late sixties and began flying a stunt plane when he was seventy. He entertained his grandchildren by doing barrel rolls and other crazy stunts while releasing smoke from the back of the plane. The grandchildren were enthralled. But I was terrified that they might be forever traumatized if their daredevil grandfather crashed to the ground. My mother-in-law Edwina hated small planes. When she came to visit us in North Haven, my father thought it would be a great treat for her to accompany him in his helicopter while he pointed out the interesting sights. He happily zoomed down to show her various small islands, not realizing that the flight was sheer hell for Edwina. She didn’t visit us in Maine again until after Daddy died.

As Daddy neared eighty, he had a few scary episodes while flying, and he was afraid the FAA might revoke his license. Usually Jimmy Brown, our Maine caretaker, helped him roll his stunt plane out of the hangar, but one day Daddy decided he would do it himself. He rolled the plane out and got in, not noticing that he hadn’t closed the canopy all the way. As the plane was taking off, the canopy opened completely. Daddy tried to close it and crashed the plane. Jimmy heard the noise and came running. He saw Daddy emerge from the ruined plane and go into the house. When he came back out, he was as cool as someone who had taken a minor spill while roller skating.

“Well, I guess I did that right.”

“What did you do?” asked Jimmy.

“I took a slug of bourbon, two tranquilizers, and ordered a new plane.”

The next problem was dealing with the corpus delicti. Daddy didn’t want the FAA to find out about the crash, so he and Jimmy flew over to the mainland in another plane and rented a truck, which they took back on the North Haven ferry. Jimmy dismantled the plane and they loaded it into the truck. My father hired someone to drive it to Vermont and deliver it to one of his flying buddies, who then got rid of the “evidence.”

My father’s second love was sailing. I began spending time on his yachts when I was a young girl. Daddy had different yachts over the years, each suited to his style of life at that time. They were all called Palawan after a beautiful island in the South Seas he visited at the end of the Second World War. The earlier boats were more geared toward racing, the middle ones were for adventure and travel, and the late ones were for comfortable family cruising. I can remember him building a mock-up of the main cabin of one of our Palawans in his study in our Greenwich home. I loved sailing on the Palawan on lazy summer afternoons, with my father towing me behind on a raft and the cool salty water streaming over me. He became quite a renowned ocean sailor, winning the Bermuda Race several times, and he later traced Captain James Cook’s voyages in the Pacific.

When I was a junior at boarding school, my father invited my roommate, Suzannah Hornburg, and her father to sail back with us after the Bermuda race. They both accepted, neither having had much experience sailing. I said to Suzannah in a superior tone, “You will probably get seasick, but I never do.” We started off in beautiful weather. But by the second day the sky was looking ominous, and we wound up out of radio contact for several days, caught in a hurricane. My father reveled in the storm. He was the old man against the sea. He organized a sea anchor behind the boat to stabilize us and slow her down. All the men wore harnesses to attach themselves to a railing, because there was a real danger of being blown off the slippery decks. Suzannah and I, banished from the deck, stayed in a cabin below, scared witless. Everyone (myself included) got seasick. Here is my father’s description of the storm:

We had cleared St. George’s Channel in the morning and by nightfall were about 60 miles off the islands, when Bermuda Harbor radio began forecasting strong winds in our area. We battened things down for a rough night, and the wind, blowing about Force Six by midnight, had increased to a full gale by dawn. By noon it was gusting to well over 70 knots.

The crew was below except for our professional, my son Tom, and myself, and we had our hands full. We had moved progressively down to a reefed mainsail, storm jib, no mainsail, then no sail at all, and finally we began to prepare for a full hurricane. We had oil ready in one of the heads to pump overboard if necessary to calm the seas, and running before the gale with bare poles, we trailed astern two long loops of rope, which were secured on opposite sides of our taffrail. These helped greatly to slow the boat and quiet the seas, so that the cockpit filled less frequently. But to carry the ropes from the foredeck, where they were stored, to the stern was a major task. I found I couldn’t stand against the wind, but had to crawl forward slowly, snapping and re-snapping my safety harness as I went. The roar of the wind was monstrous and the only way to communicate with anyone else on deck was by hand signal.

My father made his most ambitious sail in 1974, when he was sixty. Three years earlier, in Greenwich Hospital, recovering from a heart attack that prompted his retirement from IBM, he began dreaming about sailing up the coast of Greenland to Etah, the abandoned Eskimo settlement where Admiral Robert Peary started the final leg of his voyage of discovery to the North Pole. Wanting a boat for voyaging, rather than speed, Daddy summoned Olin Stephens, the yacht designer, and Paul Wolter, the professional captain of the second Palawan, a fifty-eight-foot yawl. The three of them sketched out plans for a successor Palawan, a sixty-eight-foot ketch. It was built at a boatyard in Bremen, Germany, and in 1973 Daddy sailed it home across the Atlantic so he could learn its quirks.

The voyage to Greenland was not for the faint of heart. My father and his crew of seven threaded their way between submerged “blue band ice” and giant cakes of white ice on the surface. A telegram interrupted the voyage: YOU MUST COME HOME. His brother Dick had died, and Daddy flew back for the funeral. He left my mother in Connecticut to console my aunt Nancy, and he returned at once to the Palawan. “I was in no state to be of use to anyone,” he said. The Palawan managed to get far north of where any pleasure boat had gone, but was stymied by thickening ice. Daddy and his crew were only 150 miles from Etah and 770 miles from the Pole.

My father was crazy about motorcycles and rode them throughout his life. He also had motorcycles for his children to ride on, and Olive and Lucinda were great enthusiasts. He often rode his motorcycle to work at IBM, dressed head to toe in black leather. Then Superman would go into his office and emerge like Clark Kent in a conservative pin-striped suit.

In 1967, when he was fifty-three, he went to Zermatt and had an exhilarating time skiing the lower heights of the Matterhorn. True to form, he became obsessed with climbing the Matterhorn, one of the highest mountains (14,692 feet) in the Alps, straddling Italy and Switzerland. This was another of his “dream” adventures that he fulfilled after leaving IBM. Recently my sister-in-law told me the story of Daddy’s climb. Evidently, his guide Paul Julen said “I can get you up, but I can’t get you down.” Daddy insisted, and so they started at 10:30 at night, and after climbing all night, arrived at the top at mid-morning the next day. A helicopter was flying overhead, and Paul said, “Lie down.” Daddy lay down, indicating he couldn’t climb down, and eventually had an exciting transfer by rope to the helicopter, which couldn’t land on the peak. When Daddy got back to the base of the mountain, he called President Jimmy Carter and said: “I just climbed the Matterhorn, so I guess I can be ambassador to Russia.” He was appointed in the summer of 1979, in the third year of Carter’s one term in office.

Daddy at the summit of the Matterhorn

Typical of a man of action, my father sometimes got out ahead of himself. Two of my younger sisters spent a summer in Lapland, Finland, participating in an international program and staying with a family there. While visiting my sisters, my father impulsively invited two of the family’s daughters to visit us in New York. This turned out to have been a somewhat misguided decision, as neither of my sisters especially liked the “Little Laps,” as we called them. Daddy flew them to New York and immediately took them with the family to dinner at Lutèce on East Fiftieth Street, at the time a very fancy and expensive French restaurant that was one of his favorites. The Little Laps dozed through every course, and later fell sound asleep at the Broadway production of Fiddler on the Roof. Everyone, including the Little Laps, breathed a sigh of relief when the visit ended.

My father on his unicycle (photo by Toni Frissell)

Daddy liked nothing better than scooping up a group of kids and taking them on an adventure—on his boat, out camping, or simply in one of his old cars to get ice cream cones. When I was in ninth grade, he invited me and a group of my friends for a cruise on his boat. This made me briefly popular with my Greenwich Country Day classmates who came along, but two weeks afterward I felt as isolated as ever.

When I was sixteen, we rented a house in Camden, Maine, where my father had spent summers growing up. One lovely summer day, my father, Helen, and I sailed to a nearby island and cooked hamburgers for lunch. Just as we were finishing we heard a voice. My father leapt up, his face white, and started searching the uninhabited island. After we’d made sure that no one was there, we got on the boat and headed for home. Daddy turned to me and said, “Jen, did you hear a voice?” I replied that I had but hadn’t been able to hear what it was saying. My father told me the voice had said, “Are you all right, Tommy?” He then said the only person who’d ever called him Tommy was his father, who had died years before. Daddy remarked that he was going through a hard time at IBM that summer. When we arrived home we told my mother about the voice, but she didn’t take the account seriously. My father went on to deny it had happened, but years later he admitted it had. I thought about the voice: analyzed it with my friends and ultimately decided it was some beneficent being (my grandfather?) interested in my father’s welfare.

My father used to buy all sorts of cheeses and delighted in tasting them. He enjoyed some classical music and would listen to Tchaikovsky over and over. He loved the ballet, and while I was at college I was thrilled when he gave me two tickets to see Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev in Romeo and Juliet. Years later, when he was the ambassador to the Soviet Union, he went to the ballet as often as possible. My mother told me that, before attending a performance, he would listen to the music and dance some of the steps in his dressing room.

He and my mother also enjoyed ballroom dancing, and my father wanted his daughters to be good dancers. Occasionally he would take my mother and some of his older daughters to the Maisonette in the St. Regis Hotel on East Fifty-Fifth Street, where he’d dance with each of us in turn.

My father admired my love of books, and sometimes he’d ask me to recount the plots of novels I was reading. I remember in particular giving him a summary of Crime and Punishment when I was in my teens. I told him how Raskolnikov felt he had the right to kill a pawnbroker because he could use her money to greater good. Daddy was fascinated by this moral inversion and cited it in some of his speeches. Later, when I was running Books & Co. on Madison Avenue, he kept asking for a definitive list of the hundred great books, so that he could start reading them.

He was also passionate about poetry. He grew up at a time when it was a much greater part of the school curriculum than it is now, and when memorization was an important part of study. He liked Kipling, and “When Earth’s Last Picture Is Painted” was one of his favorites. At age twenty, he memorized a parody of Robert W. Service by Edward E. Paramore Jr., “The Ballad of Yukon Jake.”

Daddy practices his signature in his schoolboy poetry book

OH THE NORTH COUNTREE is a hard countree

That mothers a bloody brood;

And its icy arms hold hidden charms

For the greedy, the sinful and lewd.

And strong men rust, from the gold and the lust

That sears the Northland soul,

But the wickedest born, from the Pole to the Horn,

Is the Hermit of Shark Tooth Shoal.

Oh how I loved the word “lewd.” When I pronounced it slowly, it sounded almost pornographic. I have my father’s old poetry text from high school, and it is touching to see how he practiced his signature on the endpapers of the book.

After six years in high school, Daddy’s blurb in the Hun School yearbook

My father’s late interest in literature was his way of making up for what he had missed at school. To say that he was no scholar is an understatement. He stayed back two grades in high school, and when he finally graduated from the Hun School in New Jersey, he had been rejected by Princeton and everywhere else. “Tommy, get in the car,” my grandfather said. “We’re going to drive around the country until we find a college that will accept you.”

Good fortune struck when they visited the admissions office at Brown University. This is how my father described the way my grandfather introduced himself: “’I’m Tom Watson, I run the IBM company, and my son would like to consider coming to Brown. By the way, who is the president of Brown?’”

“The admissions guy said, ‘Clarence Barbour.’”

“’That’s very interesting,’ said Dad. “’He was my pastor when I lived in Rochester, New York.’”

“We went to Clarence Barbour’s office, said hello, and Barbour got somebody to show us around campus. When we returned, the admissions officer was looking at my record. He said, ‘He’s not very good but we’ll take him.’”

Daddy lived up to his low expectations. He failed American history twice, provoking the professor to say, “I would like to welcome all the new class members—and hello again, Mr. Watson.”

The wheels had been greased for my father, and not for the last time. When he joined IBM, he was the fair-haired boy, because he was the boss’s son. By throwing business his way, and advancing his career, his supervisors hoped to advance their own. He spent his whole life trying to get out of his father’s shadow and prove himself a success in his own right. I can see, in retrospect, how much pressure he put on himself, and how much of it he brought home with him. When his safety valve blew, and he lost his temper, everyone in the family paid the price.

My father loved to sing and tell jokes, and he had a gift for accents. A lot of his stories would be offensive today, but in the ’50s ethnic humor scarcely raised an eyebrow—except if you were the butt of the joke. Once he told one of my younger sisters a rhyme that began:

Ching ching chinamen sitting on a fence

trying to make a dollar off of fifteen cents

When she told this to her second-grade class, her teacher, Ms. Chang, was not amused.

When Daddy was relaxed and happy, no one was more fun. But he could erupt at any time. You could be talking to him as if he were the easiest person in the world, laughing and having a great conversation, and then something would set him off, and he’d become a totally different and scary person. “WHAT DO YOU MEAN BY THAT!” he would demand in a threatening voice through gritted teeth. Then I would frantically backpedal and try to smooth things out, but by then the damage had been done.

Daddy believed in quite a regimented schedule for us. Even on weekends we had to be up, dressed and down to breakfast at 7:30—no sleeping in! (Today on weekends I still get a kick out of lounging around in my bathrobe!) We usually had some family activity, such as a bike ride, or sailing on my father’s boat. During the summer not much spontaneity was involved, as we had to announce at breakfast what we were doing for lunch or dinner, and once “the help” had been alerted, there was no going back!

We had quite an early curfew, and when we were invited to parties, my father made me call to make sure an adult would be there… Also: Absolutely no TV during the day, and only two hours a night on weekends. Turn off all lights before you leave your room. I can remember that, one night, when we were out, my father, removed from our rooms all the lightbulbs that had been left on, and then, when we returned, chuckled in his room while we complained that something was wrong with the lights. When we were at our ski house in Vermont, we had to be on the lifts when the slopes opened, and we couldn’t come home until they closed.

Greenwich was very bland and waspy in the ’50s, and my father felt his daughters should have husbands that would fit in. Once, when I was around seventeen, I was going up in a chairlift with him, and my father asked me, “So, Jen—would you ever go out with a Jew?” (He pronounced it tcheww.) “Oh yes, Daddy,” I answered eagerly, even though I didn’t know any Jews. “Would you marry one?” he went on, his voice becoming edgy. “Oh yes, Daddy,” I said, pleased to see that I was getting a rise out of him. We went through the same scenario for blacks (except he called them Negroes), with increasing agitation on my father’s part. After I married, I was delighted to learn that my husband Alex—although not raised Jewish—was the great-grandson of Orthodox Jews.

Even though my father was not big on intermixing within his own family, he was very much for equal opportunity at IBM. He even told some officials in a Southern town that he would put an IBM plant there on the condition that the company could hire an equal number of whites and blacks. At the request of Robert Kennedy, he put an IBM plant in a particularly poor area of Bedford Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. My son, Ralph, recently sent me an article citing this IBM plant as a model for how a corporation could help an inner-city community and still make a profit. At IBM my father put in place a policy barring racial discrimination, becoming one of the first CEOs of a large company to do so.

Like my grandfather, he was a staunch Democrat, which used to surprise people. Unlike a lot of wealthy people today, he believed in paying his fair share of taxes and providing services for people less fortunate than he.

As a company, IBM has maintained an ethos of social responsibility. All of Thomas Watson Sr.’s grandchildren were recently invited to the company’s hundredth anniversary. Watching a film about the history of IBM, I felt very proud of my father and grandfather.

I also posed with the famous IBM Watson computer, named after my grandfather, which showed that artificial intelligence was not as far off as most people thought. Initially developed to answer questions on the quiz show Jeopardy, it stored 200 million pages of information, including all of Wikipedia, and responded to questions posed in English. IBM Watson got a lot of publicity when it thumped two former Jeopardy champions. Beginning in 2013, the machine has been put to use in a variety of data-intensive fields, beginning with evaluating options for treating lung cancer at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

When I was about twelve I came home from Greenwich Country Day one afternoon and told my father that the other kids were teasing me about being rich.

“Are we rich, Daddy?” I asked.

“No, we’re not rich. We have some money,” was his reply.

Daddy was funny about money. Even though he owned, at one point, four houses, two apartments, a Learjet, a helicopter, a yacht, and a big collection of old cars, he felt he lived a modest life and didn’t want to discuss money with his children. He was concerned about saving money and delighted in driving in and out of the city using the Willis Avenue Bridge and avoiding the toll. Daddy suggested to my mother that she could save money by buying day-old bread at the nearby Wonder Bread factory.

Daddy was quite controlling and wanted to reach beyond the grave to determine the future of my parents’ lovely house in Maine. The house was built in two sections linked by an arched breezeway. He was afraid the six children might fight over it, so he left instructions that it should be blown up.

I remember telling this to Fran Lebowitz, who responded in great indignation, “How can your father blow up a house? I need a house!”

My mother responded by blowing up half the house. I could imagine my parents’ discussion in the afterlife—my mother, with wide eyes hands raised to her mouth, saying: “Oh, Tom! You meant the WHOLE house?”

When I launched Books & Co. in my early thirties, half of the start-up funds were lent to me by my father. I was advised to make it a corporation and told my father smugly that this was great, because it meant that if the bookstore went bankrupt, we wouldn’t have to pay anyone back. He was horrified by my cavalier attitude. “If the bookstore fails,” he said sternly, “you and I will pay back every single publisher and vendor that is owed money.” After I thought about it, I realized he was right, and when Books & Co. closed, twenty years later, I repaid everyone.

When I was young and went on trips with the family, I knew I was traveling with an unusually handsome and charismatic companion—think, an early version of Jon Hamm. I could hear people whisper, “There’s Tom Watson of IBM.” Aside from being handsome, he had the kind of magnetism that attracted every eye in the room. If my mother was an “it” girl, my father was an “it” guy. Often my dates would come to see me and end up falling in love with my father, or else my mother—though husband-to-be Alex mercifully didn’t develop a crush on either one, just one on me.

The eye-catching IBM man in an official corporate picture

When we travelled, my parents would frequently be invited out for dinner by the American ambassador or a country’s political leaders or royalty. My father seemed to know everyone and had friends in every big city, not a few of whom were on the board of IBM. Some of the board members were presidents of major companies all over the world. Our family was featured in Sports Illustrated and Life, and Daddy appeared alone in countless others.

In 1957, my parents built our ski house in Stowe. With the help of a local architect, my father and mother designed the house so that it had two dormitories: one where all the girls slept and the other for my lucky brother, who could fill the space with his friends. The house opens up into a cathedral-like space with various “conversation pits” (which were big at the time). An open counter marks off the kitchen, making it easy to cook and serve. The house, now owned by my brother and my niece, is like a ’50s museum, with Eames plastic chairs (now quite valuable) in front of the kitchen counter, and other period pieces. We loved it as kids, and still do.

My father teaches my brother how to shoot in Life

Life profiles the Watson family

I’m on the top of the heap on Sports Illustrated’s cover

Downstairs in the basement was a play area for the children, with a ping-pong table and a seating area with a few board games. One year when we were teenagers we had a New Year’s Eve party down there, and my father later heard that the lights had been switched off around midnight. After that, he had an electrician rig up a light in his bedroom that would go on as soon as the lights in the basement went off. There would be no hanky-panky going on under his roof.

There are still signs in my father’s handwriting posted around the house, as though he is speaking to us from beyond the grave:

Turn off the lights when you are out of the room.

– The Management

My parents were both good skiers and made sure we all had private instruction so that we could be good as well. The family went on skiing trips to Vail, Zermatt, and Squaw Valley. One sunny day in Vail, my sisters and I were lathering our faces with sunscreen in different strengths, and just as I’d announced I was using a lotion with a SPF of 50, my mother swept over and said emphatically, “Don’t talk about the numbers—your father doesn’t believe in them!”

My father could be quite ingenious when it came to punishments. I remember my little sisters, after committing some offense, were made to drag their donkeys around the property in North Haven. When one of my sisters, a four-year-old at that time, was whining while we were out on our lobster boat, he left her on a bell buoy and didn’t come back for ten minutes. My mother would send me to my room as punishment—which in fact was a treat, since I could do what I did best: lollygag about and read.

I read so much that my father called me Madame Nose in Book. Once, in total frustration at my obsessive reading, he said threateningly, “I am going to build you a little castle in France where you can read all day.” I thought this would be wonderful and imagined myself as the “Little Lame Prince,” reading as much as I wanted and flying around on my magic carpet to view my kingdom.

Away from work, my father was always in motion—flying, ballooning, riding motorcycles (or his unicycle), tooling around in old cars. He crammed all sorts of activities into our trips abroad. He was also a natural leader. If he had been an infantry officer, men would have followed him over the top, whatever the risks. Brendan Gill, a friend of mine, described this quality in a passage quoted in Lynne Tillman’s Bookstore, which recounted my days running Books & Co.:

He was one of the most extraordinary people I ever met, truly charismatic—a cheesy word now, charismatic, but he was, to the point where if he told you that something was so, it was not only so, but you would back it with your own life. For example, once he invited me to fly up to Stowe for a skiing weekend, and we were to meet in Westchester. A blizzard came, and the airport was closed. “I’m going out, do you want to come, Brendan?” I said, “Of course I’ll come.” Because it was Tom Watson. It was a plane he had not flown often before, and he was going to fly himself—he had a copilot, but he had a book of instructions spread on his legs, and then he said into the microphone, “I’m taking responsibility for this flight, and I’m getting out of here.” They put the lights on and we went off in the snow. When we got up in the air, it turned out that the airport in Stowe was also closed, and Tom had gotten in touch with somebody and they opened up another airport somewhere else, and we came down at another airport, newly plowed, just for us, and Tom. This was the commonplace.”

At my father’s funeral, Vartan Gregorian succinctly captured the virtues and flaws of his friend:

Tom Watson was an extraordinary man, a complex man. He was both an actor and an observer. He was an independent man, a man of humor. Who else, after all, would take the president of Brown in a helicopter and right before takeoff say, “I’ve only had two heart attacks so don’t worry.”

He was a man of laughter. He was a man of anger. He was an energetic man, demanding, impatient, hot-tempered, difficult, kind, generous, and a wonderful man. Tom was an idealist yet steeped in reality, a visionary who was master of all the details to make his vision a reality. He was an unyielding and relentless competitor, a pragmatist who disliked ideological dogmatists and exhibitionists on the left as well as on the right of the political spectrum. He was devoted to his friends and valued integrity, loyalty, and competence. A man of privilege, he considered service to one’s community, one’s nation, one’s country a social and moral obligation.

Before my father died, when he was very ill and in the hospital, he put a large sign on the door: “No Religious People Allowed.” This was the last sign from a man who liked to put up signs everywhere. My family and I had been vacationing in Florida, and I called when we returned on New Year’s Eve to ask my mother whether I should come out that night to visit, but she discouraged me, and the next morning he was dead. Quite a New Year’s resolution! I don’t think he had enjoyed his life after his stroke six months earlier, as he had no longer been able to ride a motorcycle or fly his plane by himself. His last meal was a McDonald’s Big Mac, which he asked my mother to pick up on her way to the hospital.