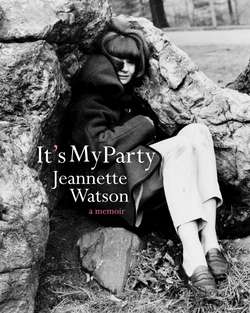

Читать книгу It's My Party - Jeannette Watson - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Two

My grandfather and grandmother, Thomas and Jeannette Watson, lived in a double townhouse at 4 East Seventy-Fifth Street, between Madison and Fifth. My grandfather bought the fifty-foot-wide mansion in 1939 from Stanley Mortimer, an heir to the Standard Oil of California fortune and a descendant of John Jay, the first chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. The house was built in 1896 for the McReady family and designed by Trowbridge, Colt and Livingston in the French Renaissance style. The McReadys lived there with seven servants. When Mortimer bought the house, he put in a bronze gate designed by Carrère and Hastings. In 2006, the house was sold for $53 million, at the time the highest price ever paid for a Manhattan townhouse.

My grandfather was a self-made man, the personification of the American dream. He was born in a small house in Painted Post, New York, to parents newly emigrated from Ireland, to avoid the potato famine, but originally from Scotland. One time my father visited the Watson homestead and found the house being rebuilt after a fire. Daddy said to the workmen, “I didn’t know my father grew up in a house as nice as this.” One of them said, “Hell no—this is much bigger than his house. It’s the house he would have liked to have grown up in.”

Grandfather attended a one-room schoolhouse and later, for a short time, a business school. One of his early jobs involved selling musical instruments from a horse and buggy. One day, while at work, he saw a bar, tied up his horse, and got drunk. On leaving the bar, he saw that his buggy had been stolen, along with the musical instruments. He vowed not to drink again and amazingly kept his vow. Much to the dismay of their guests, my grandparents served only one small glass of wine before dinner at their parties. After that, it was cold turkey!

In fact, my grandparents met at a dinner party, where my grandfather looked down the table and saw that my future grandmother was the only other person not drinking. (I feel I would have been biased the other way if I noticed a man not drinking!)

After an undistinguished early career, he started flourishing while working for the National Cash Register Company in Dayton, Ohio, where he met and married my grandmother. My grandfather and thirty-eight other NCR employees were accused of unfair business practices and were tried and convicted. He appealed, and the case was dropped. Grandfather argued with the top executive John Henry Patterson and was fired at age forty, just as he married my grandmother.

He came to New York, penniless, to look for work. My father told me that my grandfather, in order to present a good front and impress any employer, hired a limousine to take him to his interviews. Ultimately he was hired by an obscure company, the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company, and became the driving force behind its transformation into IBM.

Grandfather literally went from rags to riches. At one point he’d owned only one suit and had to wrap himself in newspapers while waiting for it to be cleaned. By the time I knew him, he looked very distinguished, always formally dressed in three-piece suits made by Henry Poole of Savile Row, Winston Churchill’s tailor. In the summer, he wore white suits and a Panama hat with a broad brim. Years later, on a trip to London with Alex, a man at Poole’s showed me the records of my grandfather’s suits. My father, who had his clothes made at Chipp in New York, never matched his elegance.

Grandfather became general manager of Computing-Tabulating-Recording (CTR) Company in 1914, the year my father was born, and its president in 1915, when he was forty-one years old. My grandfather has been called “the world’s greatest salesman,” and he was among the first to create a distinct corporate culture. His salesmen dressed in suits, ties, and white shirts, giving them more self-respect and a greater ability to connect with their customers. As children we often mocked the inspirational slogan THINK. We used to sing “THINK spells think: that’s our family motto.” IBM had its own symphony, country club, and songbook. In 1936, my grandfather amazingly earned the highest salary in America—$365,000, which would be around $6 million today.

As one of the highest-paid men in America, it seemed fitting that my grandfather raised his family in the wealthy suburb of Short Hills, New Jersey. My father remembers that some of the neighboring families considered the Watsons to be “nouveau,” and they were often excluded from the more “exclusive” parties. This probably accounts for my grandfather’s determination to see his family rise in society. I wonder what his old neighbors in Short Hills thought when my grandfather became FDR’s man in New York, entertaining heads of state and royalty. I heard that, because of all the IBM stock he acquired, my grandfather’s chauffeur became one of the richest men in Sweden when he retired there.

I loved spending the night at my grandparents’ house in the city. My mother would drop me off and, suddenly, instead of being part of a big family, I was an adored only child. When I came up the big marble staircase to the third floor, where the bedrooms were, I turned to the left, toward the street-side of the house. At the end of a long hallway were two bedrooms, one on each side of the hall. To the left was my grandparents’ bedroom, with bathroom. They slept in a double bed. Across from my grandparents’ room was another large bedroom with twin beds, which was where I slept. I felt the energy of the city when I heard street noises outside as I was going to sleep.

A large formal portrait of my grandparents’ four children hung on the wall of “my” bedroom. There was also a television, and often we would watch a program (sometimes Lassie) as we ate our dinner. Tables would be set up in front of each of us for our dinner trays. (The townhouse was later owned by the arts patron Rebekah Harkness, and, ironically enough, a real estate agent asked me, years later, if I would like to buy it for Books & Co.)

My grandfather called me his “Precious Promise,” perhaps because I was the oldest female grandchild. When I stayed with him in New York, we would often spend mornings walking to Central Park to feed the ducks or watch the boats racing near the Hans Christian Andersen statue. Sometimes we went on horse-and-buggy rides, and I got to sit up front, next to the driver, and occasionally took the reins. Other times, my grandfather would take me into a toy store and tell me the happiest words a child can imagine: “What would you like? I’ll get you anything you want.” I always wanted a doll.

My grandfather with his “Precious Promise”

When I was about three, my grandfather took me on a business trip with him, just the two of us. We went to Poughkeepsie so that he could check out an IBM plant. I remember sleeping in the same bed and feeling happy and secure. Years later, when I went to my father’s retirement party, an ancient woman approached me and identified herself as my grandfather’s secretary and she said “I remember your grandfather asked me to give you a bath.” I can’t imagine a CEO of today asking his secretary to bathe his grandchild.

I never felt the same unselfconscious love of my father. I felt awkward just holding his hand. It was completely different with my grandfather. He wasn’t scary, he wasn’t going to scream at me, he just loved me. I could sit in his lap in a way that I never could with my father. I felt totally adored.

Daddy describes his tumultuous relationship with his father in his autobiography, which I recently reread and found far more revealing than I had previously realized. “From very early in life,” my father admitted in the first chapter, “I was convinced that I had something missing. I was never able to connect with what other people were doing.” I was shocked to read: “Father [my grandfather] must have known he had an uncontrollable temper that might feed on itself, because when there was punishing to be done, he made Mother do it…I would go up to their white-tiled bathroom. Father would stand near the basin to observe, I would hold onto a towel rack, and Mother would do the switching.”

Visiting Grandfather at IBM

It is painful in every sense to imagine this ritual, and it also seems weird that my grandfather would stand by as spectator. I can only imagine that these switchings had a devastating effect on my father and possibly increased his feelings of anger as an adult.

As a grownup, I could never reconcile this gentle man with the harsh taskmaster who had such a fraught relationship with my father. The switching of my father seemed so out of character, as did my grandfather’s harsh words to him when he was a boy and later at IBM. Both of them had explosive tempers, and their frequent fights at work would often end in tears. I suppose they had become rivals of sorts at IBM, with my grandfather wanting to stay in charge and my father impatient to take over.

In front of the Thomas J. Watson Library at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (photo by Joyce Ravid)

For all of us grandchildren, the townhouse was like a palace, with marble floors and a huge winding staircase. Near the staircase was a tiny jewel-like elevator with a red-velvet interior and a tiny plush velvet bench. We loved playing in it and rode up and down endlessly. I remember a large, dark living room where sometimes the grandchildren would sit on the floor while Grandfather showed us a painting. I remember in particular a depiction of a Western landscape, where all the cows were encircled by bulls to protect them from marauding Indians.

He gave my parents a Monet for their wedding present and was an early collector of Grandma Moses. He became a patron of the arts, and the Salmagundi Club, founded in 1871 as a gathering place for artists and collectors, honored him with a dinner on his seventieth birthday. The boy from Painted Post was on a membership roll that at one time or another included William Merritt Chase, Charles Dana Gibson, Childe Hassam, Norman Rockwell, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Stanford White, and N.C. Wyeth.

As a flower girl at my Aunt Jane’s wedding

My grandfather used to amaze me with his “tricks.” He had very strong hands and could crack a walnut with them; I would then get to pick out the delicious meat inside. He had dentures on the side of his mouth, and I can remember him making those teeth disappear and reappear, which I thought was nothing short of miraculous.

I have a weakness for beautiful clothes, and it was my beloved grandfather who put me on the road to perdition. He brought me exquisite coats, bonnets, and dresses from Paris. One year for Christmas he gave me a white ermine muff, which sent me over the moon.

The first dress I remember was the one I wore as a flower girl in my aunt Jane’s wedding. It was long and pink, with a flowered pink organdy overlay and a pink satin sash. The ensemble was completed with pale pink slippers and a small dainty bouquet of tiny pink and white flowers. I felt like a princess. I remember waiting to walk down the aisle, gazing at my aunt Jane in her lovely dress, saying somewhat too loudly, “Aunt Jane, you look so beautiful!”

I have such sharp memories of my grandfather that my granny seems pale by comparison. She looked like a storybook grandmother (which no one does anymore), with white hair in a kind of twist at the back. She was partial to somewhat shapeless dresses and sensible shoes. For any formal occasion, she wore a hat covered with lots of little flowers. One of my grandfather’s biographers said she was homely, but I don’t think that was true. Surprisingly, she had her underwear custom made, and once gave me a lovely slip in pink satin with my monogram (J.K.W., the same as hers) written in blue lace at the top. My grandmother was an accomplished equestrienne in her youth and, riding sidesaddle, won many silver trophies. Some of them—monogrammed with her initials, J.K.W.—came into my possession as her namesake.

A different side of Grandmother comes out in a story written by Catherine Small, later Catherine Keesey, in the Wheaton College alumni notes about her first year there, in 1902:

Wheaton never encouraged visits from beaux. Not many men had the courage to call on a girl there. One day, to my amazement, I received a note from Charlotte Keesey’s older brother, Vincent. I hardly knew him and thought his mother had probably asked him to come see me. I asked permission to have him call and it was granted and the day set. The windows in Metcalf Hall were full of girls watching for Vincent, for we were not allowed to introduce a caller to anyone, but had to entertain him in a formal reception room. At last Vincent came and we were seated in stiff chairs facing each other and I was doing my best to be entertaining when suddenly there was a knock on the door. I said, “Come in,” and who should appear but Jeannette with her hair pulled back tight in a knot and dressed as a maid with a white apron and said in the most awful Irish brogue, “You’re wanted at the telephone, Mum.” I tried not to look amazed and excused myself and left the room presumably to answer the telephone. When I got outside I found no one in sight so in a few minutes I returned. Not long afterwards there was another knock and when I said, “Come in,” Nell appeared in a black dress with a dainty sheer white apron and cap, looking as pretty as could be, with a tray with tea and said, “Would you like some tea, Miss?” I thanked her and she put down the tray and I poured tea. I tried to act as if this was what happened when a man called on a girl at Wheaton. The girls were determined to see Vincent and he and I laughed many times over his visit to Wheaton for I married him a few years later.

Granny was quite old-fashioned about what things were and weren’t suitable for me. When I was fourteen, all the girls my age wore Tangee, a hideous lipstick with an orange tinge. One day, I wore it on a visit to my grandmother. This was the first time I had taken the train by myself to New York. A black man was seated across from me. Around half-way into the city he opened his fly, pulled out his penis, and began to masturbate. I was like a deer caught in the headlights and couldn’t decide what to do. I felt it might be rude to move my seat, as he seemed to be working so hard and earnestly. I watched respectfully and was relieved when he finished, though I didn’t exactly understand what had happened and never mentioned it to a soul. After meeting my train, my grandmother immediately called my father to tell him that lipstick was unsuitable for a fourteen-year-old girl. My father got furious with my mother, who in turn was not happy with me.

(My father was also horrified when, at fifteen, I started to wear eye makeup. One night before a date, I came into the library, where my father was interrogating my terrified cavalier. He saw me enter the room and said loudly, to my utter mortification, “What’s that black junk on your eyes?”)

On that same visit, I think, my grandmother took me to the movie Marjorie Morningstar, which captivated me—at least for a while. She thought it was too risqué and made us leave about halfway through, taking me instead to see A Dog of Flanders, which I didn’t enjoy nearly as much. But she encouraged my reading, and we always went to the bookstore together to pick out a new title. When we returned to her apartment, she would read aloud to me, even when I was quite old.

My uncle Dick even built a small house for her on his property in New Canaan after my grandfather died, and during the summer, if my father had to come back from Maine to work at IBM, he used to stay with her.

My father told me that my grandfather’s character was so strong that my grandmother’s personality was overshadowed. But she was no pushover. As my father recounted in his autobiography, Grandfather put endless demands on her in the early days of IBM, and after ten years of strife she asked for a divorce. “I told him I couldn’t stand it anymore”—words that were strikingly similar to the ones exchanged between my father and mother after his heart attack.

My grandfather and Queen Wilhelmina in 1942

“Tom,” my grandmother told my father, “he looked so shocked, so upset, that I realized how deeply he loved me—and I never brought it up again.” After she made the decision to preserve the marriage, she never complained again. If a crowd showed up and she had no one to help in the kitchen, she’d smile and say, “The cook is off today, but we have some sandwiches and fruit.”

In 1938, my grandparents took a tour abroad, stopping in Albania, Greece, Romania, England, and France. It was all very grand. They hobnobbed with now-forgotten kings, queens, and lesser royalty, as well as assorted aristocrats and political leaders—the “highborn,” as my father put it.

In Albania they were received by King Zog and his lovely young wife, Geraldine, and they dined on solid gold plates, with dinner and dancing until 3:00 a.m.. As they traveled, there were rumblings of war and much anxiety. My grandmother would later describe England’s war preparations, including the evacuation of children. My grandparents traveled with a lady’s maid, Ernestine, and my grandfather had a valet—all very Downton Abbey-ish!

In 1942 Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands paid a visit to the United States, and my grandfather was her escort and even gave a birthday party for the future queen Juliana! That same year he wrote a book: An overview of the historic visit of Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands to the Dominion of Canada and the United States of America.

Holiday reunion at Meadowcroft Lane. (I am the tallest girl; my brother, the second boy.)

The entire Watson family—my grandparents, their four children, and their spouses, and eventually eighteen grandchildren—were together for all major holidays and frequently spent time at my grandparents’ country house in New Canaan. The third generation sat at the children’s table, and my cousin Mary Buckner and I, as the two oldest girls, were in charge of making sure the little ones behaved.

In the late ’40s and ’50s, when IBM had country clubs for its employees, the company had “family” parties for the IBM family. I remember going to one as a little girl with my grandfather and singing along to the IBM rally song:

There’s a thrill in store for all,

For we’re about to toast

The corporation known in every land.

We’re here to cheer each pioneer

And also proudly boast

Of that “man of men,” our friend and guiding hand.

The name of T. J. Watson means a courage none can stem;

And we feel honored to be here to toast the “IBM.”

EVER ONWARD—EVER ONWARD!

That’s the spirit that has brought us fame!

We’re big, but bigger we will be.

We can’t fail, for all can see

That to serve humanity has been our aim!

Our products now are known, in every zone,

Our reputation sparkles like a gem!

We’ve fought our way through—and new

Fields we’re sure to conquer too

For the EVER ONWARD I.B.M.

EVER ONWARD—EVER ONWARD!

We’re bound for the top to never fall!

Right here and now we thankfully

Pledge sincerest loyalty

To the corporation that’s the best of all!

Our leaders we revere, and while we’re here,

Let’s show the world just what we think of them!

So let us sing, men! SING, MEN!

Once or twice then sing again

For the EVER ONWARD I.B.M.

Over the years, sons and daughters of IBM employees have mentioned to me how much the Country Clubs meant to them. One said to me, “I would never have learned to swim if it hadn’t been for IBM.”

When I look back at the paternalistic culture at IBM in those days, and compare it to the way big companies operate today—with their impersonal human-resources departments, obsession with profits and share price, and astronomical executive salaries—I can’t help but think that corporate America has lost its heart. Business leaders were admired when my grandfather and father ran IBM. They were celebrated in newspapers and national magazines, not just because they brought prosperity to the country, but also because they had a personal connection with their employees and their customers.

At an IBM Christmas party. I am on Santa’s lap.

Mummy, Grandfather, Daddy, Grandmother, and three girls. I am the tallest!

With Grandfather: “I felt totally adored.”

One of the lovely letters Grandfather wrote me—in this case, after I swallowed a pin.