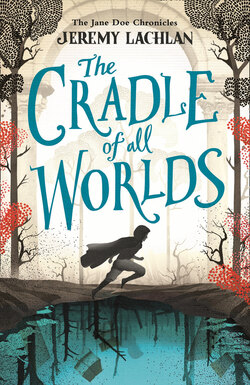

Читать книгу The Cradle of All Worlds - Jeremy Lachlan - Страница 10

ОглавлениеTWELVE YEARS LATER

I’m in trouble again. Occupational hazard when you’re known as the Cursed One, the Unwanted, the Bringer of Bad Juju, a Djinn. Bad weather, spoiled crops, missing pets – I always cop the blame. I don’t have a clue what I’ve done this time. All I know is, Mrs Hollow’s performing another cleansing ritual at the top of the basement stairs, spitting on the landing, flapping a sprig of thyme. Muttering things like ‘repugnant abomination’ and ‘catastrophic blemish of unfathomable proportions’ under her breath.

Clearly, she’s been looking up big words in the dictionary again. Never a good sign.

Normally, I’d settle in for the long haul. Sit in the shadows, chew my fingernails, hum a tune. Not today, though.

Today, I actually have somewhere to be. Today, I have a secret.

I step into the wedge of light cast by the open door. ‘Um. Mrs Hollow?’

‘Shh!’ The woman’s tall and lanky. Twitchy eyes ten sizes too big through her glasses. Basically a six-foot-tall praying mantis on the edge of a nervous breakdown. She pulls half a lemon from the pocket of her apron and squeezes it along the doorframe. ‘Need to focus.’

‘Right. The spit-and-twirl. Sorry.’

Mrs Hollow ditches the lemon and thyme, spits on her hands – ptooey ptooey – spins in a circle and shouts, ‘Be gone!’ Then she freezes with her hands held high, fingers splayed.

Nothing happens, of course, but it sure looks impressive.

‘Good one,’ I say. ‘Thing is, I’m kinda busting for the loo –’

‘Ugh. Damn it.’ Mrs Hollow snaps out of her trance and wipes her hands on her apron, shakes her head. ‘It’s gone. The vibe. You’ve ruined it. I’ll have to start again.’

‘Maybe if you just told me what it is you think I’ve done –’

‘Not you. Well, not just you. Him too.’ She jabs a finger over at my dad, lying in his little alcove, still awake but calm at last. We live in the basement, see. Rats and all. ‘Keeping us up all night, shrieking like a banshee. We’ve had it! Learn to control him or he’s out.’

My face flushes red hot. ‘It wasn’t his fault. The quake scared him is all.’

‘The quake you caused, you freaky-eyed little –’

‘Beatrice! ’ a voice screeches from upstairs. Her husband, Bertram, a little weasel of a man perched semi-permanently at the kitchen table. He hardly ever leaves the kitchen because a) that’s where the food is, and b) he’s terrified – of everything. Germs, animals, pollen, books, simple human contact, me. The man squealed at a coathanger once, I swear. ‘Give her The Speech. ’

Uh-oh. Anything but The Speech. Not now.

‘Excellent idea, Honey-Bucket!’ Mrs Hollow stares down at me, suddenly so earnest, so wounded. ‘This is how you repay us, is it? We take you in, purely out of the goodness of our hearts. We feed you. Employ you. Heck, I even bathed you when you were a baby, and all you can do to show your appreciation is keep us up all night? Well, let me tell you something –’

The woman drawls on, but I learned to ignore her a long time ago.

Sure, some of it’s true. The Hollows really did take me and Dad in, but only because they drew the short straw. Nobody wanted us after we showed up on Bluehaven, so the town council threw the names of every couple on the island into a barrel and picked the lucky winners. Half an hour later, we were dumped on the Hollows’ doorstep with two chickens and a cow to soften the blow. There’s no ‘goodness’ in their hearts. They have no friends, they pretend Violet – their own daughter – doesn’t exist, and they’ve treated me like a slave for as long as I can remember. I clean the outhouse, do their laundry, collect eggs, milk the cow, shovel manure and mop the floors, all while caring for Dad full-time.

Jane Doe, Jack-of-all-trades.

‘Are you listening, girl? I said that is why you deserve a horrible, lonely death.’

‘Oh.’ My turn now. ‘I apologise, Mrs Hollow. You’re absolutely right. I’m a bad seed. Rotten to the core. I promise I’ll try harder in the future. Ma’am.’

Thankfully, the woman’s never been good at catching sarcasm.

‘Good. We’ll be leaving for the festival in a few hours. You know what to do.’

I nod. ‘Stay here. Stare at the wall. Pray for forgiveness. Same as always.’

‘Precisely. The Manor Lament is an important day for us all.’ She jabs a finger at me. ‘Don’t ruin it! With any luck, the Makers will grant us mercy this year,’ she adds, meaning with any luck I’ll be struck by lightning, attacked by rabid dogs or stung to death by bees.

‘We can only hope,’ I say, but I’m pushing it.

Mrs Hollow frowns at me, then nods at Dad. ‘Keep. Him. Quiet.’ And with that, she steps back and slams the door.

‘Finally,’ I mutter.

I skirt round my raggedy mattress on the floor and duck into Dad’s alcove, squeeze alongside his bed. He barely slept at all last night, thanks to the quake. Tossed and screamed, sweated through his sheets. Just like the quakes, his outbursts have been getting worse lately. More intense. Almost violent. Now his big brown eyes are glazed again, fixed in that thousand-metre stare. Most people would see an empty shell of a man, but I know better. The slight crease in his brow. The tremble in his hands. I know he’s in there somewhere, and he’s scared.

He wants me to stay.

‘Thought she’d never leave,’ I say, forcing a smile. ‘You doin’ okay?’

He doesn’t answer, of course. I’ve never actually heard him talk, not once.

Caring for Dad’s the one chore I like. It’s hard work. Beyond sad. I have no idea what kind of nightmare he’s stuck in, and I gave up trying to guess a long time ago. Sure, he can stand and walk if I help him. A slow two-step shuffle. He can drink and chew and swallow, use the toilet in the corner, but that’s pretty much it. He can’t talk. Can’t laugh. Can’t hug me. I can’t play games with him or take him outside. Worst of all, I can’t make him better. All I can do is plump pillows, tuck blankets, spoon soup, tear bread, brush teeth, wash hair, trim fingernails, and ask myself the same old questions that have drifted into my head for years: What was he like before he got sick? What’s his real name? When did his hair turn this premature, smoky grey? What were his favourite foods, colours, seasons and songs? And the bigger questions: Where did we come from? What was my mum like? What’s her name? Does she have eyes like mine? Is she out there somewhere, waiting for us on the Other Side? Why isn’t she here with us? In short, what really happened the night we came to Bluehaven?

I know Dad has all the answers – he must – but they’re trapped inside him, like scuttling bugs in a jar. All I can do is imagine. Some days it drives me mad, but I love him, simple as that, which means I wouldn’t have things any other way. Sure, I wish he’d snap out of it and steal me away from this place, but wishes are dangerous, distracting things. This is our life. Always has been, probably always will be. At least, that’s what I used to believe.

Now I’m not so sure.

I woke at dawn to a quick ratta-tat. Wiped the drool from my chin and the sleep from my eyes just in time to see a note slip through the crack in the tiny basement window. Not just any note, though. An old photograph. A picture of Dad, sleeping in a chair in a grand, sepia-toned study: still sick, I think, but slightly younger, his face less lined. I felt like I’d swallowed an anvil. I’d never seen a photo of him before. I dragged a crate under the window and stood on my tiptoes, desperate to see who left it, but they’d gone. I held up the photo to the milky light and that’s when I noticed the message on the other side.

My place. White Rock Cove. 10 a.m. Come alone if you want answers – E. Atlas

Eric Atlas. It didn’t make any sense. Still doesn’t. Bluehaven’s illustrious new mayor skulking around town at dawn, sneaking messages through windows? The guy was here in the house just a few weeks ago. I didn’t see him, of course, but I could hear him through the basement door. The heavy boots. The gravelly voice. He said he was checking up on the Hollows, sat in the kitchen for an hour while they listed their grievances, so why all the secrecy now? Why today? I paced and pondered, scratched my head. Debriefed, plotted and planned with Violet when she snuck down to say hi before her parents woke up.

You have to go, she said. It could be a trick, but you have to go.

And she was right. It probably is a trick. A ploy to lure me out into the open. Festival shenanigans or something, I dunno. But I have to go. I have to risk it, have to know.

This feeling doesn’t come along every day, the feeling that everything could change.

I pluck the crumpled photo from under Dad’s pillow. Best hiding place in the basement. Dad has a blanket tucked over his legs in the photo, and there’s a desk beside him. A fireplace, too. Behind him, a cabinet stocked with books, weapons and vases. It sure as hell wasn’t taken in the Hollows’ place, so where was it taken? And when?

Dad’s breath quickens. I hold his hand, give it a squeeze.

‘Don’t sweat it, Johnny-boy. I’ll be back before you know it.’

I need to hurry. The old clock on the wall says it’s almost nine-thirty, which means Violet’s signal should come any moment. Just a diversion, I told her. Nothing crazy. Don’t blow anything up. She promised, crossed her heart and all, but I saw the glint in her eyes.

I tie my hair back – long, dark, so knotted I swear it’d snap a comb – then shove the photo into my pocket and kiss Dad on the cheek. ‘I’ll fix you something to eat later on, okay?’

I turn away, don’t look back. Leaving him alone is hard enough as it is.

There was a time when I could squeeze through the basement window, but those days are long gone, so I grab my cloak and creep up the basement stairs. The Hollows won’t lock the door till they leave, so getting out’s no problem. Even so, I sit tight a moment, breath held.

Then it happens.

There’s a sharp crack. Somewhere out back, I think. Mrs Hollow yells, ‘Not again! The bucket, Bertram, where’s the bucket? Violet! You get back here now!’

I smile.

The girl’s incorrigible. Eight years old and already a pyromaniac.

The back door screeches open, which means it’s time to move. I step out into the hallway, ease the basement door shut, and sneak down to the front door as quickly and quietly as I can, doing my best, as always, to ignore the Three Laws hanging above it, framed and embroidered, covered in a fine film of dust. Standard in every house on Bluehaven.

We enter the Manor at will

We enter the Manor unarmed

We enter the Manor alone