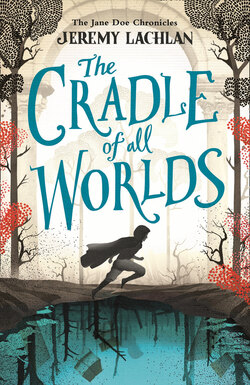

Читать книгу The Cradle of All Worlds - Jeremy Lachlan - Страница 17

ОглавлениеTHE MANOR LAMENT

There was a time when I was obsessed with the Otherworlds. I used to sneak into the storeroom of the Golden Horn and hide behind the barrels of ale, listening keenly as the old folks at the bar told their tales. Back in the basement, I’d re-enact them for Dad, dwelling on the fine details of these different places, these worlds without curses and curfews. Better worlds where smiling wasn’t a punishable offence, and maybe – just maybe – Dad could walk and talk and play. Maybe even a world where Mum was waiting for us both with open arms, ready to take us home – to our real home.

It was a prospect too exciting to ignore.

I even used to love the Manor Lament. Locked in the basement, I’d listen through the open window, trying to guess which stories were being celebrated, savouring the scent of barbecued sausages and sugar-roasted nuts. Come nightfall, I’d cheer on the unseen fireworks, every crack and bang. Marvelling at each flash of light that burst over the neighbouring stone wall like a shattered rainbow. I pictured stars exploding over the island and wondered if you could catch the pieces as they fell. But all of that was way back when. Before I understood what the meaning of the word outcast truly was. Before I realised the festival was damning me and Dad.

The Manor Lament quickly slipped into the long list of things I couldn’t care less about. The sounds, the smells, the stories, the very idea of the Otherworlds themselves. That mythical home-sweet-home. I bottled up the desire to embark on a quest to find my mum, buried it deep. I knew I had to make a choice. Spend my life wishing for something that would never be or focus on what I had. What was there, right in front of me. What was real.

Caring for Dad. Protecting him.

Now I’m about to become the festival’s star attraction.

And Dad’s gonna be all alone.

My prison-on-wheels rattles and clanks up the road to Outset Square, drawn by the horse. I can only just hear Violet’s voice over the racket, which is good, seeing as she chose the worst hiding place in the history of stupid hiding places. She asks how I’m holding up.

‘Peachy,’ I mutter through frozen lips.

‘Hang in there, kid,’ she says. ‘At least you finally get to see the festival, right?’

Nobody notices us when we emerge from the alley. Atlas, Peg and Eric Junior stop the horse beside a cluster of barrels and wait, soaking up the scene. The ecstatic crowd. The busy food stalls. The flags, banners and confetti tinted pink in the light of the setting sun. The jugglers and fire-breathers. Barnaby Twigg striding around the well, twirling a sword.

I spot Mr Hollow in the crowd, desperately trying to avoid touching anyone, a handkerchief clasped to his mouth. Mrs Hollow’s laughing and clapping beside him. The effigies of me and Dad haven’t been lit yet, but they’ve been used as target practice for eggs and arrows. A group at the base of the Sacred Stairs chant and shake their hands in some sort of ritualistic dance. Kids watch, enthralled, as red-faced old-timers act out their Otherworldly adventures on every stage, complete with homemade props. Battles with beasts. Epic wars. Narrow escapes from ancient, booby-trapped temples. The whole square is a heaving mass of people, colour and noise.

The Manor looms above it all, silhouetted against the golden, sunset sky, its features lost in shadow. I can’t help but feel it’s staring down at me, a hungry toad watching a fly.

I can’t hold its gaze for long.

That’s when I realise Mr Hollow’s looking right at me. He flaps his handkerchief at me. Grabs Mrs Hollow’s arm. She sees me too, and turns a dirty shade of green.

They scream together, long and loud. An ear-piercing, blood-curdling shriek.

One by one, the performers stop performing, the jugglers stop juggling, the fire-breathers let their flames die to curling wisps of smoke. Barnaby keeps on marching and singing until a rogue sausage flies from the crowd and hits him in the chest. Then he too stops and stares along with the rest of the crowd.

And a grim, heavy silence settles on the square.

‘What’s happening?’ Violet whispers. ‘Why’s it so quiet?’

I feel naked, exposed, like a hooked worm dangling over a school of fish.

‘Um . . . hi,’ I say to everyone.

Mr Hollow clutches his chest. Someone lets out a stifled cry. Old Mrs Jones faints into the arms of some idiot dressed in a bed-sheet toga, but Atlas doesn’t miss a beat.

‘Fear not, good citizens of Bluehaven. The Cursed One is our prisoner at last!’

A collective gasp ripples through the square. I signal Violet to run with a jerk of my head. She stares defiantly back. The crowd doesn’t know what to do, what to feel. Relief ? Happiness? Terror? They aren’t sure whether to celebrate and cheer or dash home and hide. But Atlas stirs them up, milks them for all they’re worth. He assures them of their safety, my treachery, his undying love for them all, and sure enough the good sheep of Bluehaven start a goddamn slow-clap. A slow-clap that quickly turns into outright applause. The idiot in the toga drops Mrs Jones and kisses some guy standing next to him. The Hollows even hug for three whole seconds.

‘The Cursed One attacked a group of perfectly innocent fisherfolk five hours ago in White Rock Cove!’ Atlas cries. ‘Ran at them with a machete! Threatened to kidnap their firstborn children! When they tried to flee, she herded them onto a jetty and tried to drown them all. Tried to sink the whole island with another quake!’ Cries of outrage from the crowd now. ‘But my son leaped onto a nearby boat, trapped the beast in a fishing net, and brought her ashore to face her crimes!’

Eric Junior flashes a cheesy smile and punches the sky. Everyone hoo-rahs and huzzahs and sends gleeful praises to the Makers. It’s amazing, to be honest. Insane, but amazing.

Atlas raises his hands, silencing the rabble. ‘The sentencing, Gareth, if you please.’

Peg unfurls a scroll from his vest and clears his throat. ‘By the powers newly entrusted to ’im as Mayor of Blue’aven, the Honerababble Eric Nathaniel Atlas, son of ’ighly esteemeded adventurer Nathaniel Constantine Atlas, does ’ereby sentence Jane Doe, daughter of what’s-’is-face Doe, to – ’ang on, can’t read me own writin’. What’s that last word there?’

‘Death,’ I say, adding in a much quieter voice, ‘idiot.’

‘Oh yeah – DEATH!’

Surprise, surprise, the crowd goes wild. Right on cue, a bunch of fisherfolk haul large wicker baskets through the crowd, handing out rotten eggs, fish, fruit and vegetables.

‘Fourteen years ago, this filth and her father intruded upon our world,’ Atlas cries above the uproar. ‘Cursed our home!’ He pulls the Manuvian knife from his vest. ‘Now her death shall set us free! Gone are the days of injustice! Gone are the days of fear and sorrow! Tonight we end our long years of suffering! Tonight we take destiny into our own hands!’