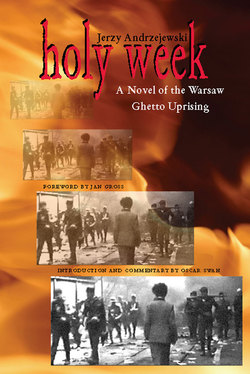

Читать книгу Holy Week - Jerzy Andrzejewski - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Jerzy Andrzejewski’s Holy Week

JERZY ANDRZEJEWSKI’S NOVEL Holy Week deserves recognition as one of the most significant literary works to appear in Poland in the years immediately after the war. Its absorbing and tightly knit plot, its nearly documentary realism, and the momentous nature of the subject matter—the Warsaw Ghetto uprising of 1943—set it apart from its contemporaries. Few fictional works dealing with the Second World War have been written so close in time to the events themselves. None treats as honestly the range of Polish attitudes toward the Jews at the height of the Nazi extermination campaign.

Andrzejewski’s novel, or novella, has been infrequently reprinted. It has not been widely translated into languages other than German (editions in 1948, 1950, 1964, and 1966). The relative popularity of the work in Germany probably stems from the fact that it is a story about the Holocaust in which Poles, not Germans, are the primary actors. The 1993 Polish edition, on which the present translation is based, lists the dates of the novel as 1943–45; the two years refer to two different versions of the same story. The earlier and shorter version was never published, and its manuscript has not surfaced. It is known only from the recollections of listeners to whom it was read in secret wartime literary gatherings. Apparently it focused on the moral dilemma of the protagonist, Jan Malecki, a recently married Pole upon whom is thrust the decision whether to shelter a Jewish woman acquaintance.

Andrzejewski had always been an outspoken critic of anti-Semitism. One possible factor prompting him to rewrite the first version of Holy Week, giving greater prominence to the largely apathetic attitude of the Poles toward the Jewish uprising, was the appearance in the immediate postwar period of anti-Jewish manifestations across the south of Poland, particularly in Rzeszów, Tarnów, and Kraków. The statement of the fascist Zalewski, that one can be grateful to Hitler for having resolved the “Jewish question,” mirrors declarations made at various postwar right-wing political gatherings.

In Holy Week, as in many of Andrzejewski’s works, personal considerations begin to overshadow abstract questions of right and wrong and to affect the decision-making ability of the main character. Jan Malecki feels increasingly estranged from the irritating Jewish woman, Irena Lilien, with whom he had once been close, and wonders whether he has done the right thing by risking the safety of his family (his wife, Anna, is pregnant) to save her. Irena, for her part, has been inalterably changed by the traumas of her wartime experiences. A member of a prominent, privileged, and acculturated Jewish family of banking and academe before the war, she has been forced for the first time in her life to think of herself as a Jew, because that is how others now view her. Importantly for the plot, Irena has a distinctively Semitic appearance.

The rewritten version of the novel adds to the personal dilemma of the central character the broader context of Poles’ attitudes toward the “Jewish question” and the plight of the Jews locked in the ghetto during the final moments of its existence in 1943. In both its versions, Holy Week by all accounts went over among listeners and readers like a lead balloon. Critics passed over the work largely in silence. Andrzej Wajda’s film version of the novel, issued some fifty years later in 1995, had a similar reception. Andrzejewski’s work touched—and still touches—a number of raw nerves, which one would do well to enumerate here.

Poles, having lost a greater percentage of their people than any other nation in a Holocaust in which percentages and numbers ceased to have meaning, were in no mood in 1945 to read about a temporizing hero’s vacillations over whether to harbor a Jew during the war. Even less interested were they in reading about Polish anti-Semitism, the whole gamut of which is openly and honestly displayed on the pages of this novel, seemingly for the first time in all of Polish literature. For their part, Jewish readers were loath to appreciate a novel on the ghetto uprising as seen from the outside, whose protagonists were Poles and in which the central Jewish character is a spoiled, whiny, and self-centered young woman.

Some readers questioned the decency of fictionalizing events so horrific as to defy any recounting other than the documentary and statistical. The ease with which Andrzejewski moved from real-life human drama to fictional depiction before the ashes had even cooled, as it were, scandalized some for whom the war was not the setting for an action novel, but their own personal experience as well as that of numerous friends, relatives, and comrades who had not survived. Of course, equally justifiable reservations regarding facile fictionalization could be raised regarding the author’s much more positively received work, Ashes and Diamonds (Popiół i diament, 1949)—and they were raised, but without impugning that novel’s status as one of the major literary monuments of postwar Central European literature.

It is true that Andrzejewski applies the niceties of the prewar novel of moral choice to a wartime situation unprecedented in its terror, brutality, atrocities, and sheer level of destruction—a feature some readers found disconcerting. One of the novel’s main themes, however, is the very inadequacy of the attitudes, values, and traditions with which the prewar Polish intelligentsia had been imbued. Indeed, they had negative survival value in dealing with a historical cataclysm of such magnitude that it indifferently and indiscriminately crushed everything and everyone before it, whatever their attitudes or actions.

There was also the question of the author’s political motives. The Soviets were now in power, and Andrzejewski was perceived by some as currying favor with the authorities by casting prewar Polish bourgeois society as by and large indifferent to the plight of a sizable and ethnically distinct segment of its population.

It is not endearing to the public in Poland for an author to criticize either the Catholic Church or the Polish national character. Although Andrzejewski does not exactly do either, the pages of Holy Week are nevertheless saturated with the irony of a situation in which workaday Warsaw citizens, under the canopy of an immense cloud of smoke, baked Easter loaves, bought flowers, rode merry-go-rounds, mouthed pieties, and crowded the churches against a background of constant gunfire and street executions of Jewish escapees. The novel virtually forces the Polish reader to recognize himself among the busy shoppers and idle onlookers at the spectacle of the ghetto’s last days. The novel’s very title and the device of using the days of Holy Week to chronicle the stage-by-stage demise of the ghetto uprising underscore the irony that reaches its peak on Good Friday, the day in the New Testament calendar on which the Jews demanded Christ’s crucifixion.

The immediacy with which Holy Week strikes the reader stems in no little part from the author’s presence as an eyewitness to the actual historical events. Together with Maria Abgarowicz, his future wife, the author occupied an apartment on Nowiniarska Street that looked out not only on the walls of the ghetto but also on the carousel being set up for the Easter holidays. This carousel, on which merrymakers rode, brushing ashes out of their hair while the ghetto burned its last, was the one immortalized by Czesław Miłosz in his poem “Campo di Fiori.” The apartment house became the model for the setting of Jan Malecki’s surprise encounter with Irena Lilien on the first day of the Jewish uprising.

The church at Wawrzyszew. Photo by O. Swan

Andrzejewski later moved with Maria, who was by that time pregnant with their son Marcin, to a house in the northern Warsaw suburb of Bielany, the site of the fictional villa populated by Jan, his pregnant wife, and a cross-section of other Warsaw inhabitants ranging from the seedy and bigoted Piotrowski family to the landlord Zamojski, with his aristocratic last name, elegant library, and liveried servant. Warsaw streetcar number 17, which Jan rides to and from town, still wends its way from Mokotów in the south, through downtown, and along the ghost walls of the ghetto, to arrive finally in Bielany, now more firmly incorporated into the city limits than it was in 1943. To the west of Bielany still lies the settlement of Wawrzyszew, with its connected ponds and small church near which Anna prays.

The fictional name Irena Lilien may have been taken from a family with whom the author briefly stayed in Lwów following his flight from Warsaw in 1939. Andrzejewski himself stated that her character was modeled on Janina Askenazy, the daughter of the renowned historian Szymon Askenazy. Most others have identified the prototype as Wanda Wertenstein, Andrzejewski’s companion from 1941 to 1943, a prominent Polish postwar film critic. Irena’s picture is undoubtedly a composite.

Andrzejewski has been characterized by Czesław Miłosz as a dramatist in a novelist’s garb. Indeed, the novel’s action takes place within a compressed period of time, Tuesday through Friday of Holy Week, and largely within the confines of the Maleckis’ Bielany apartment, from which forays into the city provide an ever-changing dramatic contrast. The action is propelled almost entirely by the direct speech of the characters, whose every utterance is accompanied by such specific descriptions of voice, tone, gesture, and attitude as to make the transformation of the novel into a play or film seem anticipated. Wajda’s film transcribes entire passages from the novel nearly verbatim.

The characters also seem chosen according to the principle of dramatic economy: each represents a type, and no type is represented by more than one character. The three main characters (leaving aside Irena for the moment)—the architect Malecki, his wife Anna, and his younger brother Julek—seem typecast according to the canons of Polish literature stretching back to the nineteenth century. Irena herself, whose options for action are limited by external circumstances, and who therefore plays a passive and reactive role, is not so much a literary stereotype as she is a lost individual, hounded and doomed by an unjust fate.

Malecki is the ratiocinating and rationalizing liberal. He has all the right instincts and sensibilities but is unable to act on them in a direct and timely fashion. In his occasional moments of clarity he realizes that his every move has been taken in service of his own ease and comfort. Anna is the veritable embodiment of the Matka Polka (Polish Mother)—warm, nurturing, instinctively moral, deeply religious, and committed to family and fatherland (ojczyzna). Julek is Malecki’s polar opposite in all ways, including his rejection of hearth and home for the national cause. Although the character has been criticized for being left-leaning, nothing Julek says allows one to pin a specific political affiliation on him. His values lie outside himself, and he is committed to giving them embodiment through action.

Andrzejewski would have been among the last to downplay Poland’s heroic resistance to the German occupation or the suffering endured by the Polish population at large; in fact, this suffering is a major motif in the novel. Anna Malecka loses almost her entire family in the war, whether in the initial invasion, in prison camps, or through random misfortune. One may add to this the barely alluded-to tragedies of the Makarczyński and Makowski families and the unnamed next-door neighbors taken away in the middle of the night. Thousands of instances have been documented in which Poles risked their own lives and those of others to save and shelter Jews, more than in any other country. Authorial honesty, however, demanded that not every moment of a novel about the ghetto uprising be draped in the national flag. Not every Pole played the role of hero; among them were extortionists, informers, collaborators, and outright fascists and Nazi sympathizers. The Polish underground resistance group Żegota, while sympathetic to the Jewish cause, judged that the time was not yet ripe for a general open revolt against the Nazis and provided only token help to the insurgents: handguns and a few rifles and hand grenades. Most Poles, even if they were troubled about the plight of the Jews, went through the war as did Jan Malecki—carefully, one step at a time, doing their everyday jobs and looking after their own interests. Often they were successful in tiptoeing around disaster, though sometimes they were not.

Much of Polish literature is inaccessible to a broader audience, not only because of the language barrier but also because of the specific national problems occupying the minds of many Polish writers. Such criticism cannot be raised with respect to Holy Week, which is, perhaps, more easily appreciated by an English-speaking readership than by the postwar Polish audience for whom the novel was originally intended.