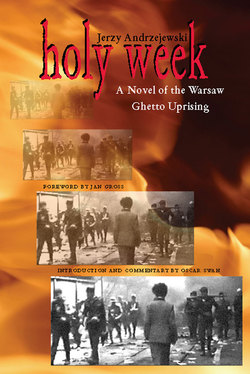

Читать книгу Holy Week - Jerzy Andrzejewski - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

AS A BRILLIANT NOVELIST and prose writer, Jerzy Andrzejewski is a rare specimen in the firmament of Polish literature, which abounds in extraordinarily talented poets. Two of his contemporaries, Czesław Miłosz and Wisława Szymborska, received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1980 and 1996 respectively, and while Andrzejewski lived, there was an aura of expectation that he would be awarded a Nobel as well.

Andrzejewski’s literary career spanned the entire short twentieth century and a gamut of ideological positions. Just before the war in 1939, he received the much-coveted Young Authors’ Prize of the Polish Academy of Literature for a collection of short stories and his novel Mode of the Heart (Ład serca), and he was hailed as a rising star of Catholic literature. Shortly after the war, his novel Ashes and Diamonds (Popiół i diament) was widely admired as an artistically brilliant portrayal of the new political era that had dawned in Poland with the accession to power of the Communist Party. Later this book was turned into a cult film by director Andrzej Wajda and gained international acclaim. Andrzejewski was lionized by the new regime, and his intellectual fascination with the new aesthetics of Socialist Realism was dissected in major works of literary criticism, including, among others, The Captive Mind, which his friend Miłosz wrote after going into exile in the West.

Holy Week gives artistic representation to what became for a number of distinguished Polish intellectuals a dramatic realization—the abandonment of the Jews to Nazi persecution by the dominant Polish society. Naturally, the story line of Holy Week and its moral and existential dilemmas are all-important for the development of the individual characters. But of crucial importance in the narrative is the background of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. A number of great Polish writers (notably Adolf Rudnicki and Mieczysław Jastrun, both of whom were assimilated Jews) have noted the callous indifference of Warsaw’s inhabitants to the tragic fate of the insurgents and the remaining residents of the ghetto. A steady shower of ashes sifted down for days from a cloudless sky as German SS and police detachments charged with suppressing the uprising set fire to this part of the city, and to its Jewish population, creating the greatest conflagration in Warsaw’s history.

In addition to Andrzejewski’s novel, which offered the first artistic examination of the drama, the events of the ghetto uprising inspired works by other writers. Miłosz wrote a stunning poem on the subject published after the war in his volume The Rescue (Ocalenie). Miłosz and Andrzejewski were the closest of friends during the Second World War, which they endured together in Warsaw. They worked together—quite literally, for it was a handmade edition of only a few dozen copies—on the underground publication of Miłosz’s Poems (Wiersze), written under the pseudonym Jan Syruć. The imagination and sensitivity of the two friends were tuned in the same key. They saw each other every day, and when Andrzejewski moved with his family to a larger apartment across town from the Miłoszes, they wrote long letters to each other, which Miłosz published much later in a volume of correspondence, Legends of Modernity (Legendy nowoczesności).

After 1956, following the period of “thaw” and de-Stalinization in the Soviet bloc countries, Andrzejewski became one of the most outspoken members of the critical intelligentsia. In time he turned in his party card, signed petitions demanding greater freedom of expression in artistic and political fields, and was recognized as an iconic figure of intellectual opposition to the Communist regime in Poland. When Poland joined with other Soviet bloc countries in the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia—to suppress Alexander Dubček’s “socialism with a human face” and the liberalization of the Czechoslovak regime—Andrzejewski wrote a public letter of apology and solidarity addressed to Eduard Goldstücker, president of the Czechoslovak Union of Writers, which had been at the forefront of the movement for reform. In 1976, he was among the founders of the Workers’ Defense Committee (Komitet Obrony Robotników, KOR) in Poland, an unprecedented initiative in which intellectuals openly provided legal and financial assistance to workers repressed by the Communist regime after a wave of strikes. KOR transformed politics in the Soviet bloc and led directly to the formation of the Solidarity movement in August 1980.

Jerzy Andrzejewski’s creative powers slowly waned, succumbing to alcoholism. In spite of his progressively incapacitating illness, he left a formidable oeuvre that is compelling not only because of his skills as a storyteller but because, like all great literature of the twentieth century, it bears testimony to the fragility of the human condition.

Jan T. Gross Princeton University