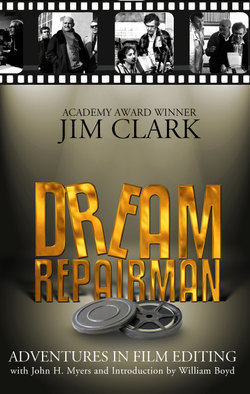

Читать книгу Dream Repairman - Jim BSL Clark - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеVERY FEW FILM EDITORS OF Jim Clark’s stature and renown have written the story of their working lives. Editors are, in a way, the unsung heroes and heroines of filmmaking, a fact that makes The Dream Repairman both a timely and remarkable book. Here, we have rare and firsthand testimony from the cutting room and, the editor’s voice is always one to heed.

I first met Jim Clark in the early 1980s, over a quarter of a century ago, through his wife Laurence Méry-Clark, who was the editor of the first film I wrote, Good and Bad at Games (1983). After Laurence introduced us, the Boyds and the Clarks began to see each other socially from time to time. It turned out we had mutual acquaintances. Frederic Raphael and John Schlesinger, for example. Thus our friendship fortuitously began.

My professional association with Jim started a little later when my third film, Stars and Bars (1988), was produced at Columbia Pictures when David Puttnam was head of the studio. Jim had moved to Los Angeles with Puttnam to be a senior executive at Columbia, and I remember having lunch with Jim and Laurence at their rented house in Los Angeles while I was on a trip out there. I think Jim was gently shepherding Stars and Bars through Columbia though it was eventually released after David Puttnam’s tenure and when the Los Angeles period of Jim’s life was also over.

Our friendship continued back in London but we worked together again on the film of my first novel A Good Man in Africa (1994), with Jim editing, and with me as the writer/co-producer. Bruce Beresford was director but Bruce had to leave us early during post-production to shoot another film he had committed to and, consequently, Jim and I were thrust together to see the film through some of its post-production phases. I remember a particularly fraught afternoon in a Wembley sound studio supervising the recording of the score, Jim and I tentatively taking turns giving the composer our somewhat critical notes.

All this is by way of a preamble to explain why, when I eventually came to direct my first film, The Trench (1999), there was only one editor I could possibly choose as far as I was concerned. I asked Jim and, luckily for me, he said yes, with one caveat: He would have to leave almost immediately after the shoot and the first assembly of the film to go and cut the new James Bond movie, so someone else would have to take over for the rest of post-production. And who better than his wife, Laurence, who had edited the film of my first screenplay? Full circle, of a sort. So I claim this unique first: I am the only film director ever to have had his film cut by the husband-and-wife team of the Clarks. I was extremely fortunate, and I knew it.

When I first met Jim, I was aware of his reputation in the industry. The legendary “Doctor” Clark, the man who could make sick films healthy again. I knew about his lengthy career, his astonishing filmography, the great directors he had worked with, the films he had saved through his editorial finesse, the Oscars he had been nominated for, and the Oscar he had won. For a tyro film director like me, it was both an honour and, in many ways, an alarmingly daunting prospect to think of Jim in the editing suite waiting for the daily rushes of my film.

It turned out to be a fascinating adventure, and I wonder if my experience is common to the other directors he has worked with. Jim is a man renowned for his candour: he does not pull punches, he does not mince his words, he is fearlessly honest. Standing on the set of The Trench that first day, with Liz West, my script supervisor, I evolved a plan—not a plan of attack, more a plan of defence. Jim became a kind of admonitory ghostly presence on the set, as if he were hovering at our backs. We would shoot the scene in question and then Liz and I would go into a huddle and try to second-guess what the Clark analysis and response would be. “What would Jim think?” became our working mantra. Because we were shooting on a set at Bray Studios, the cutting room was only fifty yards away and Jim would wander over occasionally to see how we were getting on. He never said very much, but from time to time we would receive terse notes: “I need another closeup”; “This scene won’t cut together”; “This shot goes on too long”; “I need a reverse on such-and-such a character” and so forth. From our point of view the aim was to go through a day without receiving any feedback from the cutting room, without one of these dreaded notes being delivered. We grew better and better. It was, I see now, a benign on-the-job learning curve for me, and I came to understand a huge amount about how to shoot a film professionally, properly and, equally importantly, I began to realise how a film is re-created in the cutting room.

The role of editor in the collective, collaborative process that is the making of any film is massively important but not one, I believe, that is generally recognised outside the small pond that is the filmmaking community. One of the great lessons of this wonderfully enjoyable memoir is that this point becomes steadily obvious, but it is made with subtlety, discretion, and modesty. It is also a potted history of the post-war film industry in England and America and, of course, an autobiography. The trouble with writing an autobiography is that you can’t really say what a great guy you are, what fun you are to work with and hang out with, what insight and instinct you have about the art form of cinema, and how much and how many film directors are indebted to you. But I can, so now it is on the record. The Dream Repairman is a delight, a classic of its kind and so is its author.

William Boyd

London, April 2009