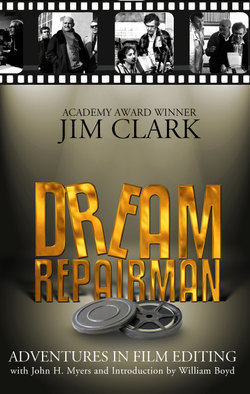

Читать книгу Dream Repairman - Jim BSL Clark - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER THREE: CARY GRANT, HOLLYWOOD,AND BROADWAY

ОглавлениеThe Grass Is Greener

Stanley’s new film was The Grass Is Greener, and he was able to attract an impressive all-star cast. Cary Grant, Jean Simmons, Deborah Kerr, and Robert Mitchum were involved in the principal roles. There can’t have been any other reason for making it since the material was thin and barely altered for the screen. It consisted of a lot of talk and was set in the aristocratic area of British life with lords, castles, and God knows what else, so it was certain to appeal to the American public. The editing phase of a Donen picture at that stage in his career was notable for the fact that you didn’t see him too often. He was very busy preparing for his next picture or having some domestic upheaval. Stanley was a great one for tests. He would spend many days testing the clothes, makeup, hair, and stock. Chris Challis, who lit The Grass Is Greener would shoot stock tests on all the Kodak material available at that time.

During the post-production of Surprise Package, when Stanley did turn up, we would run the movie in the theatre and get some feedback for changes. I don’t recall that we ran it too many times. There was a looping session with Yul Brynner, which I directed. He was Mister Speedy and broke Shepperton’s record for the number of loops recorded in a session. None of this made him any funnier. In fact, his dialogue was delivered so fast that it made him unintelligible. Stanley might have been influenced by Billy Wilder’s direction of Jimmy Cagney in One, Two, Three. One day Noel Coward was in the room. He had very few loops and to flesh out the time I encouraged him to tell us about his wartime exploits, which I had been reading about in his autobiography. Having the real Coward in the room was exciting. He ended the session by inviting me to “Sit in the Rolls with your old Uncle.” This brought me down to reality. Pity. Maybe it was one of life’s lost opportunities.

Perhaps the director had given up on Surprise Package. It did, however, have to be completed, and I remember we ran a preview one evening in Slough, where we died by inches. Stanley had requested that a recording be made of the audience’s laughter. This was a bad idea.

The Grass Is Greener was simple enough to edit since Stanley Donen shot it in a very straightforward manner leaving me few decisions to make. Like Indiscreet, it was an adapted stage play and he shot it like that. Frankly, it wasn’t really very good and relied on its stellar cast to survive.

Cary Grant was co-producer and always a pleasure to work with and for. The picture was shot in Technirama, which was Technicolor’s own Cinemascope, and I was cutting it on an old Acmade machine that had only a bull’s-eye lens through which to see the tiny image. The machine made a terrible clattering noise too, so I was shattered after a day’s editing, when we would wander into the old bar at Shepperton Studios to relax.

Maurice Binder, who had done special title sections on other Donen pictures, arranged a splendid tableau of babies for the credits, the babies representing the stars as infants, and an amusing morning was spent in the garden at Shepperton as Maurice directed these tots.

The film went together very easily and was almost fine cut when the shooting ended. Stanley took off for the south of France, leaving Cary Grant and I to supervise the music sessions that were held at Shepperton. A selection of Noel Coward’s music was arranged by Douglas Gamley. It always struck me as odd that Cary was there, hanging around the music sessions and Stanley wasn’t.

Stanley returned. We had to complete the sound mix early in order to preview the film in America, and I had to arrange for double sound crews to work day and night. I was in the dubbing room until five in the morning for a fortnight. I’d then drive home for a few hours sleep before returning again at eleven when Stanley would come to listen to the previous night’s work. Very often he’d rubbish it and demand retakes. It was a trying time and perhaps not the best way to work. Stanley was always very fussy about the condition of the work print and, in this case, ordered that the entire thing be reprinted for preview, a job that was handled by my assistant, Mary Kessel. Mary managed to complete the job just as I was ready to board the plane for Los Angeles with the print.

This was heady stuff for me. I had never been to Hollywood and here I was travelling on a 707, albeit in economy, while Cary Grant was up in first class. We had to land somewhere in Canada to refuel, and I remember Cary came back to find me and we walked around on the tarmac for a while. Cary was instantly recognised by everyone and besieged for autographs. At that time, the British public were more respectful. They might have pointed and giggled but would never ask for an autograph.

In Hollywood I stayed with Stanley at the Beverly Hills Hotel, which was a paradise in those days. I was picked up every morning by Bill Hornbeck, a famous and accomplished editor who was then head of post-production at Universal. He had a Ford Thunderbird and I loved those sunny mornings as we drove over Coldwater Canyon with the hood down en route to Universal City.

There was no Universal Tour at this time, so the view of the San Gabriel Mountains was undisturbed. I was astonished by the size of the studio, where Cary had a permanent bungalow as his office. His assistant allowed me to use the bungalow as my headquarters since Cary was rarely there.

I was fascinated by the studio. The lot seemed to extend for miles, and I would walk all over, under a hot sun, looking at the standing sets or observing units at work. I would eat lunch in the commissary, discovering cottage cheese with fruit and yogurt, generally wondering that I was there at all.

One evening Bill suggested that I might like to attend a studio preview since I would have to endure our own shortly and should know the ropes. This was a preview for a new Doris Day movie, Midnight Lace, which Bill assured me I would enjoy as it was a thriller set in London, directed by David Miller.

A bus collected all the studio personnel and took them to a restaurant. On this occasion it was a dark and gloomy steakhouse, where we solemnly ploughed our way through a heavy meal before returning to the bus which then took off for the preview theatre which seemed a very long way off in the valley. It was a hot night and, on arrival, I was surprised to see young girls lining up wearing what appeared to be pyjamas. That could never happen in Slough.

We saw the movie, which I thought fairly bad. Afterward the studio executives, clearly proud of their film, asked for my opinion of the London setting. How did it compare to the real thing? Had their advisor done a good job? I told them, in no uncertain terms, that London buses no longer looked that way, and I never saw a film that was so studio bound. I then realised that this was a mistake since these men, who thus far had treated me very warmly, now hardened and turned away, leaving me alone in the foyer as they collected the preview cards, to be read and collated on the bus ride home. I should have kept my opinions to myself and praised their film, but I have never been good at hiding my true feelings and continue to this day to blurt out my blunt opinions instead of the platitudes more readily received. Too late I realised that all these men would be in attendance at our preview and would now not be disposed to act helpfully, so I felt I’d been stupid.

The journey back was a subdued affair. Midnight Lace had played okay, but the figures were not too good and I realised that being a pariah from England was no way to make friends and influence people.

When our turn came a few nights later and this whole tiresome ritual of eating and bussing was repeated, I was ready for anything, but I didn’t foresee the technical trouble that would occur. The theatre was in Glendale and, travelling with us in the bus were both Cary and Stanley. At the theatre, to the fans’ delight, were Robert Mitchum and Jean Simmons.

I sat next to Bill Hornbeck and started getting nervous, as I still do on these occasions, made all the more anxious when the film is unmarried and held together by Sellotape. The lights dimmed and The Grass Is Greener began. Maurice Binder’s title sequence with the babies should have been accompanied by Noel Coward’s music, but there was no sound at all. Not a note of music could be heard and the babies played in utter silence. I was out of my seat in a second, followed by Bill and Stanley. Our first problem was locating the booth. None of us knew where it was and rushed about searching for likely doors. By now reel one was well on its way and the only audible sound was the slow hand clapping of the audience. I finally found the door and burst into the booth, where two t-shirted projectionists were quite unaware of the problem. “There’s no sound,” I shrieked. “Stop the show!” They were not overly impressed by this and turned to inspect the sound head. Nothing seemed amiss. Bill and I cast our inexperienced eyes over the machinery while Stanley hovered and insisted they shut off the machines. Just then I noticed a switch marked “Optical/Magnetic,” which had two positions. There was little doubt that we were still in the “Optical” mode. A quick flip of the switch and we had the sound, but we now had to wait for the reel to be rewound and relaced. At least we knew it would play and the audience settled down. The stars in the audience had been having a fine time with the autograph hounds. The film began again and near the end of reel one, I became aware of sounds that were not on the track. Minor explosive noises, which became more insistent as the reel reached its end. Stanley looked at me for some explanation, but I was just as puzzled as he. I went back to the booth and looked at the sound head as reel two progressed through it. Every so often a flash of light appeared to pass across the head, causing the “pop” I had been hearing and, as the core of the reel diminished, the flashes increased. I pointed this phenomenon out to the projectionists who remained steadfastly disinterested. They mumbled something about static charge and suggested I should touch the film as it went through, thus grounding it. So I spent the entire evening with my finger on the film, and every time I rested, the darned thing went pop right in my face. Fortunately only Stanley and I seemed at all concerned with this distraction, but I never went to a preview afterward without fully expecting a problem, and I am always a basket case afterward.

All these problems were lapped up by those executives to whom I’d played the arrogant British critic a few nights before. Midnight Lace had been a trouble-free preview, while ours was fraught with problems.

The card counting that took place on the bus produced quite a dismal result too and we retired, hurt, to Cary’s bungalow, where everyone sat around looking glum. I had the temerity to suggest we open the bar since a drink seemed the best idea, but nobody seemed thirsty and a funny look from Cary made me realise I’d transgressed some unwritten bit of preview folklore. Actually, I think it was simply his built-in sense of thrift that prompted the reaction. Cary was very typical of those wealthy men who would give you a cheque for a thousand pounds without blinking if you asked nicely, but ask for a drink from his bar or the loan of a postage stamp, and he’d give you short shrift. For example, small transistor radios were the latest technological toy, and I was longing to get out and buy one to take to London. Cary was never keen to let me off the leash and when I told him what I wanted to purchase he said, “You mean like this?” and tossed over exactly what I wanted. “Keep it,” he ordered. I thanked him and that was that. But when I suggested we all drink from his bar, it was a different story.

Finally Stanley and I retired to the Beverly Hills Hotel, where he confided that he never wanted to work in Hollywood again and told me how much he hated the system and the people. It was most unusual for Stanley to discuss his personal feelings with me. Up until then we’d never talked privately, only about the job in hand. It was quite a sad, melancholy end to a long evening. The picture hadn’t played that badly. But I guess after the failure of Surprise Package he had been hoping for a more successful result. His sadness was not all business though. He told me that Elizabeth Taylor had been his girlfriend until she was grabbed by Conrad Hilton.

We had to fly to New York for further screenings and, once again, I was travelling with Cary. On the plane I sat next to another idol of mine, Charles Walters, the director of Easter Parade, If You Feel Like Singing, and The Belle of New York, whose ear I bent for the entire trip. I think he was quite amazed when I told him I enjoyed The Belle of New York, which had been a big flop for him.

In New York we were housed at the Plaza Hotel, where Cary always stayed, and his fans were out in force as our limo arrived from the airport. I have no idea how they knew of his arrival because it was very late in the evening. It reminded me of Fred Astaire’s fans meeting him at the start of The Band Wagon.

I was quartered in the room next to Cary’s suite, and went about with him in the limo. The poor man couldn’t set foot on the street without being instantly mobbed.

These were heady days indeed. Stanley asked me what shows I most wanted to see. Gypsy headed my list. “I’ll phone Stephen,” he said and there I was talking to Sondheim who let me have his house seats. But who to take? The only girl I knew in New York was busy, so she fixed me up with a blind date, which turned out to be a girl who couldn’t stand Ethel Merman. This was a dreadful evening on the one hand and brilliant on the other. The show was fabulous and Merman was great, but I had no interest in my boring date.

The next show we attended was Fiorello. I had ditched the girl by now. The limo pulled up to the curb opposite the theatre, and I was sent ahead to signal to the car just before the curtain went up. Our seats were in the very front row of the stalls, which meant that a grand entrance was made, since Cary had to walk down the entire length of the aisle, followed by Stanley and myself. The audience recognised him at once and a standing ovation followed. It was extraordinary. The orchestra, already seated, waited until we had sat down. The remarks were often impertinent, or so I thought, calling out comments like, “Hey Cary, come on over, my wife would sure love to cook for you.” The British would never have behaved like that. I thought it really embarrassing, but he took it with good humour, and soon the show started. This was another great evening, which flashed by in a haze of pleasure as one good number followed another. During the intermission, I went for lemonades while Cary was besieged again.

Afterward we crossed the street for dinner at Sardis. I really couldn’t believe I was a part of all this. After the meal I left the restaurant and walked to Times Square, looking at the lights and gaudy displays. I thought to myself that it doesn’t get better than this. I wondered where all this magic would lead to.

Where it led to was back to Shepperton. After all this fun, we still had a picture to finish and this time we did it correctly. Stanley ran the movie a few times, trimmed and locked it, then we remixed the entire thing.

My daughter Kate was about four at the time, and I brought her to the studio when there was nobody to babysit. Cary adored her and said if he ever had a daughter he would name her Kate. He had been much married but had never had a child. Later he had a daughter with Dyan Cannon and named her Kate.

I always considered that the American trip had been a sort of thank-you gift from Cary, who knew how hard I’d worked on the film. It gave me my first extended experience of Los Angeles, a city I was to return to many times. Cary Grant was always very pleasant. He was certainly considerate, very down-to-earth, and always chatty. That was the thing about Cary. He was exactly what you would expect him to be, off the screen and on.

The Grass Is Greener was not a great hit. Stanley would have to wait until our next movie for that.

FLASHBACK: Oundle School

My brother had already completed his time there and was in the RAF when I arrived at Oundle, just as the war in Europe was ending. This school was hard for a youngster of fourteen to grasp, after a somewhat cushioned existence at Nevill Holt. I was now one of eight hundred boys and on my first day, one of about fifty newcomers, all of whom were gathered together and indoctrinated into the school traditions that had to be strictly observed or punishments would result.

I entered the same house as my brother, New House, which, despite its name, was one of the oldest, being home to about eighty boys. The older ones slept in a dormitory across the street. When I arrived, the discipline in the house was rigidly observed by the prefects, a group of eighteen-year-old thugs who were into beatings in a big way.

The house was run by Mr. Burns and his wife, who were old and had come out of retirement for the duration, so it was not surprising that the prefects held sway and used bullying tactics to keep us new ticks in order. Mr. Burns was not into beating, but his senior boys were. These older boys, who imposed themselves on the younger set, would be off to the war as soon as they left the school, possibly to be killed, so there was some reason to feel sorry for them, cruel though they were.

To display an interest in art of any kind was, I quickly learned, taboo. I had unwisely packed a Pelican paperback of Arnold Haskell’s Ballet. As soon as I was found reading that, it was snatched from my hand and thrown around the room amid cries of “Clark’s a fairy!” This both surprised and hurt me. I did not know what a fairy was in this context and I disliked being teased. The book and I both got battered that day and it led directly to all kinds of innuendoes that I did not understand.

For starters there were constant allusions to sex. Since Oundle was an all-boys school, the relationships between boys sometimes blossomed into adolescent romances. The new boys such as myself were objects of interest to the older boys, acting as girl substitutes. Occasionally this might become physical but was largely contained in country walks and afternoons by the river. When liaisons were too obvious, the younger boys might get ragged and the older boy cautioned by his superiors.

The form sexual education took at Oundle was an embarrassment to all concerned. In my case I was invited into Mr. Burns’ study during my first term and he rather awkwardly told me the basic rudiments of sex, but I could have told him more than he explained since my school friends had given far more graphic, if somewhat confusing, details on my very first day at Oundle.

There was also a local prostitute, rather uselessly pointed out as she passed the house en route to her place of work, which was the local graveyard. She had been given the sobriquet of “Fly-rip Kate.” In those days trousers were not closed with a zipper but by buttons known as fly buttons. A favourite sport among the boys was to deftly grasp another boy’s fly and rip it open, hence the term “fly-rip.”

Life at Oundle was not all horror, in fact, there was much to commend the school and I never regretted the experience. It was, for me, liberating and taught me patience and perseverance at the possible expense of damaging my emotions.

One thing it taught me, from the very start, was to be able to defecate in public without shame. Taking a shit is one of the functions of life that most of us would prefer to do in private. In New House they were determined to teach us otherwise, so there were no doors on the toilets. After breakfast the whole house descended on the bogs and stood in line waiting their turn. Woe betide the boy with even the smallest touch of constipation. Nobody was going to hang around too long. It took me a few days to get used to this arrangement, but you can adjust to anything, and before long I realised the bogs were a sort of social club, a mere part of everyday life. I never, however, adjusted to the horror of the early morning cold bath. The boys were roused from sleep around seven and went directly to the bathroom, stripped off their pyjamas, and were then ceremonially dunked into a bath of cold water. A prefect was there to ensure complete immersion. This was their way of waking you up.

When the war ended, Mr. Burns and his wife retired once again. A new housemaster was appointed. But until he arrived, New House was a mess. The boys were leaderless and apathetic. They lost all their matches and performed badly in any communal activity. Being a New House boy was altogether the pits until the new housemaster was installed. C.A.B. (Arthur) Marshall had been a boy at the school and after University had returned to be a master, teaching French. The war came, he was drafted and finally became a major in the army. He was awarded the MBE, one of the finest honours. On the beaches of Dunkirk, as the soldiers were being strafed by German dive-bombers, Marshall was entertaining them with the wild and wacky exploits of Nurse Dugdale, a female character he had invented for the BBC. Arthur Marshall was most certainly homosexual which, in those days, was hardly a trait to be flaunted. Arthur was not only the possessor of a high-pitched voice, he was also very funny.

Arthur, whom we all called Cabby, became my housemaster and that was the turning point in my life at Oundle. For one thing he inspired us. He made us think, he made us proud, and above all he made us laugh. And he kicked out all those louts who had made our life a misery. No more beatings. A dressing-down from Arthur was far worse than any physical hurt. It is very sad to inherit a group of boys that has lost its spirit and we were ready for Arthur’s magic touch. Though he had not been a housemaster before the war, he took to it directly. It must have been a difficult decision for Mr. Stainforth, the gruff and imperious headmaster, to appoint Arthur. Whether the parents were ever bothered by an obviously homosexual man being in charge of their boys I never knew. Certainly my parents were not outwardly concerned, though I doubt they knew what a real homosexual was, but Arthur was in no way interested in boys, except to attend to their welfare, which he did with enormous vigour and enthusiasm. Our position in the ratings started to rise. Before I left, New House was a positive hit and all due to Cabby.

When I arrived at the school, the projection equipment in the Great Hall was truly primitive. Two ancient machines dating from the silent period had been adapted by a science master who had attached sound heads. Picture and sound were both inadequate and frequently failed, but we did not care. Spending a couple of hours in fantasy land was enough and technical deficiencies were of no concern. I recall falling headlong for Jeanne Crain after State Fair. The senior boys were in charge of the gramophone records that played before the film, Harry James’ “Trumpet Blues and Cantabile” being the favourites in 1945. We saw four films every term, the high spot at the end of school being Field Day, involving mock warfare in fields and villages around town when we put on our OTC uniforms and played at being soldiers.

After Cabby Marshall started booking films, the choices improved, but I was now sixteen and heavily influenced, like most of my generation of cineastes, by Roger Manvell’s excellent Pelican book, Film, probably the first serious study of film appreciation to reach a wide public. It inspired many people to start film societies in their towns since there was now an interest in seeing films that could not easily be viewed outside of London. There had been film societies operating in larger cities for many years, the London Film Society began in the twenties, but the time was now ripe for expansion, and 16 mm projectors and prints were more easily obtained.

I decided to write, with generous cribs from Manvell, a manifesto that was directed toward the headmaster, to persuade him to allow me to start a film society within the school. It would be open only to senior boys and staff and be additional to the regular film shows. Arthur Marshall gave my somewhat fulsome piece to Mr. Stainforth who, much to my surprise, sanctioned the idea, provided a master was in charge and knew what films were to be shown, cautioning, “No smut please, so be cautious with the French films.” During his period in Paris after the war, Arthur had met Francis Howard who was now in charge of an organisation within the British Film Institute called the Central Booking Agency. This provided a source of films for the societies to show. It was arranged that Mr. Howard would visit the school and inaugurate the first meeting when we ran the Swiss film Marie-Louise. This was a great moment for me and eventually led to my very first job in the film industry.

The second most important decision came with the scrapping of the ancient projectors and installation of two new 35 mm machines in a soundproof booth up in the gallery of the Great Hall. Now we had terrific screenings with the enthusiastic help of Mr. Pike, the projectionist. But not before I had run Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and provided a musical accompaniment via a twin-turntable playing generous 78 rpm samplings of Vaughan Williams’ Fourth Symphony and, of course, Arthur Bliss’ Things to Come. This taught me something about film scoring that would blossom later.

The Oundle Film Society was a hit. This was 1947, and it is still active. My education was complete. Now I had to face a future in Boston, Lincolnshire, in a printing factory, while my school friends went off to University. This was not a good time. I was eighteen and trapped in a one-horse town. What to do? Start another film society of course.

Before this time, we’d been to America and back, which was very heady for a sixteen-year-old boy. The war had just ended when Alec Shennan, my father’s business friend in Chicago, invited us over. We either went on the Queen Mary or the Queen Elizabeth—I don’t recall which, but we took both boats there and back. I spent a lot of my time in the ship’s cinema, while Mother took to her bed and stayed there, fearing sea sickness. As soon as we boarded at Southampton, rationing was off. We had grown so used to eating very little that our stomachs had shrunk. We couldn’t look at the food without groaning.

In New York we were first diddled by a cab driver. Our hosts had booked us into the Drake Hotel. Our financial allowance was so pitiful that my sister Hazel and I spent most of our time in Radio City Music Hall, sitting through the stage show, and sometimes the movie, twice. Mother stayed in her hotel room. We visited the Shennan’s in Chicago where our financial straits were somewhat relieved and I bought my first Biro pen. I also visited their daughter’s school of 1,500 pupils. I was appalled by the standard of teaching and also by the pupils calling their teachers by their first names.

While there we saw both Finian’s Rainbow and Brigadoon in their original stage versions. I lugged the record albums back home. I was already very pro-American. This trip only created a greater love, which was to last a very long time.

* * *

Term of Trial

The production manager on The Grass Is Greener was James Ware, and during the course of the film we’d become friendly. We both loved popular music, and he made me laugh a lot. Jimmy had been in the air force during the war and was a live wire, extremely camp, and very funny. He had a wonderful sense of humour and, in those days, could make me laugh simply by the way he spoke. He played the piano like an angel, chain smoked, was obviously homosexual, and was wonderful at his job. He created a happy, relaxed atmosphere around him, and he was a character. The kind we don’t seem to have these days.

After the film ended, he went off to prepare another picture and was instrumental in getting me an interview with its director, Peter Glenville. The film was Term of Trial and was to be shot in Ireland at the Ardmore Studio near Dublin.

Glenville was a theatre director who’d done a few films and had written the script of this one from a novel. It was financed by Warner Brothers and starred Laurence Olivier, Simone Signoret, and Sarah Miles.

This was the period of the “kitchen sink” pictures. Room at the Top, in which Signoret had excelled was already a big hit, and Jimmy Ware had worked on that one too, being a friend of its director Jack Clayton.

That winter I found myself in Bray, a seaside town near the Ardmore Studio, with my two children and my assistant David Campling. David’s wife had agreed to join us to look after my children, though my stepson David was attending a preparatory school in England and would only be in Ireland for the Christmas holiday. He had also changed his name from Andrew to David—for reasons I never really understood. Kate attended a Catholic primary school in the town. Jimmy Ware and an assistant director joined us in the rented house.

It was something of an ordeal. The winter was cold, the house was damp, and we had a resident housekeeper who spent more time in church than looking after the tenants. The cooked breakfast she had agreed to make was always cold, sitting on top of a hot plate powered by two candles. Congealed eggs were her specialty.

Outside there were few compensations. The countryside was near and the views were fine, however, on a Sunday there was a marked lack of places to eat. At that time Ireland was not geared to tourism and unless one was a bona fide traveller, publicans were not allowed to serve alcohol.

Shooting the film was fairly simple, though the crew had no love for the director, whose lack of experience overshadowed all his endeavors. My old friend from Boston, Gerry O’Hara, was the first assistant director and delighted in watching Glenville get into a muddle with angles, more than once chuckling when the director painted himself into a corner.

The producer of the film, Jimmy Woolf, who’d also produced Room at the Top, was with us much of the time. Our cutting room was in the basement of the old house at Ardmore, next to the kitchens where cabbage seemed to be continually cooked. It was a really smelly place with the kitchen on one side and the Gents on the other.

All the principal players were staying at a nearby country hotel, once the home of John McCormack, the great Irish tenor. Once a week Jimmy Ware and I would dine there, escaping from the dampness of Bray.

One night Jimmy Woolf entered the dining room, clearly saw us, and vanished. “He’ll be back” said Jimmy Ware and, sure enough, after a short pause, Woolf reappeared and invited us to his room for an after-dinner drink. It was no secret that Jimmy Woolf was homosexual, though just how active he was I never knew. He had a long liason with Laurence Harvey, now married, and was currently escorting Terence Stamp who was also in Term of Trial.

That evening in his apartment was a long and boozy night. He kept filling up the brandy glass, and it was clear he had no desire to retire to bed. We limped out of there in the small hours. A similar evening occurred on another occasion, though this time we were in Peter Glenville’s room, along with his companion Bill Smith.

Sarah Miles made her debut in this film and was eighteen at the time. She was mostly seen with her parents, though it was rumoured that she had an affair with Olivier, recently married to Joan Plowright. This was perfectly possible, but then Olivier was often rumoured to be cavorting with ladies and sometimes with gents.

Although I’d worked with Olivier in a minor capacity on The Prince and the Showgirl, I was amazed that he remembered me. We spoke about Jack Harris, whom he admired, and of Tony Richardson and the “new wave” in Britain.

Olivier had been in the stage and screen versions of The Entertainer and was a big fan of modern cinema. I did not get to know Signoret at all, but our paths did cross again much later in our lives.

Glenville was not a difficult director to edit for. In fact, he hardly appeared after we had finished the director’s cut. The finale of the film was a courtroom scene that he shot for several days and for which I had quite a mass of rushes. I assembled the material quickly in order to see if anything vital was missing before the set was demolished but this version of the scene hardly changed thereafter.

In the editing suite, Glenville was inclined to revert to baby talk and would say, “I think a little trimmy-poo here” and such comments, but he changed very little in the film after my first assembly, and it was completed rapidly at Elstree with a score by the French composer, Jean-Michel Damase, a friend of Glenville’s.

Term of Trial was hardly a big hit, coming near the end of the kitchen sink period and not being considered a very fine example, certainly not in the same league as Saturday Night and Sunday Morning or Room at the Top. Seen now, however, it fares better though is a slightly manufactured slice of life.

Certainly Glenville had little knowledge of reality. The child of a famous pantomime couple, he thrived in a theatrical world, and the casting of Signoret and Olivier was weird. I could not fully understand their role as a couple—their mutual attraction. It was Room at the Top revisited, but not as satisfying.

However, for me, it led to a most worthwhile and important film. Through Jimmy Ware, I was introduced to Jack Clayton who subsequently asked me to edit The Innocents, a version of Henry James’ celebrated ghost story The Turn of the Screw.