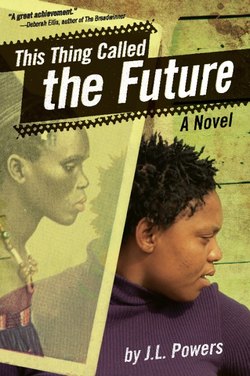

Читать книгу This Thing Called the Future - J.L. Powers - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER SIX

VISITING LITTLE MAN

Instead of going straight home, I head towards Little Man’s house, cutting through a corner alley behind Mama Thambo’s shebeen. The blue light of the television spills out through the open door, where two men are lighting up and smoking dagga. The sweet odor drifts towards me. Inside, men and women are cheering for Bafana Bafana, South Africa’s soccer team.

I wander past, ignoring the cat calls from the men standing outside. I’m deep in thought about what the sangoma told me. Usually, a visit to the sangoma is so comforting—either there’s nothing wrong or she can help you fix it. But today…

When I look up, I can already see Little Man’s yellow matchbox from a distance, crowded up against the houses next to it. His mother is growing a garden in the front yard; the corn looks like it’s ready to harvest.

Despite the worry over the witch, my stomach clenches in excitement at the thought of seeing him. I’ll pass by slowly, just once, I tell myself. Maybe he’ll be outside so I can say hi.

Seeing Little Man will make me feel better, I realize, even as I think, Gogo would kill me if she knew about this.

When I reach Little Man’s gate, his dogs run out, howling in greeting. The gate swings open and Little Man strolls out, whistling, winking at me like he knows I’m coming by to see him.

Anyway, I’ve gotten my wish and my heart leaps so far, it might as well have taken a fast airplane flight all the way to Zimbabwe.

While I’m trying to snatch it back from wherever it went, Little Man says, “Hey wena Khosi, what are you doing here?”

“I was just passing by,” I gasp.

“Where were you going?”

Now I have to find an excuse. I never pass by his house except with my family on our way to church. “I was just at Thandi’s,” I say, pointing in the direction of her house. But of course, my house is in the wrong direction to come this way. He’s going to know I wandered by this way just to see him. Oh, my God, how embarrassing.

I’m getting hot and itchy. I’m hoping he’ll ignore the fact that I wouldn’t normally pass his house. I point to the wrapped newspaper full of Mama’s muthi. “I’m just out getting some few small things for my gogo.”

“That’s cool,” he says. “My gogo sends me to the sangoma’s house to get muthi, too.”

We’re silent while I think of something to say. At school, my other friends help carry the conversation so there are no awkward silences.

I ask the first thing that comes to mind. “Have you ever gone to a sangoma when you were sick?”

He shakes his head no. His tightly coiled dreads reach to his shoulders and swing with the movement of his head. I like them. No, I love them.

“We go to the doctor if we’re sick,” he says. “That sangoma medicine, it’s all superstition and lies.”

All those warm fuzzy feelings I have for him dry up in defensiveness. I don’t want to argue with him, but I can’t keep my mouth shut. “These herbs really help my grandmother with her arthritis.”

“I bet doctors have some medicine for your gogo’s arthritis that will help her a lot more than a bunch of old herbs.”

“But herbs are natural, not like the medicine you get from doctors,” I protest.

“Do you really believe in all that ancestor stuff?” Little Man asks.

“You don’t?”

He shrugs. “I don’t know what I think.”

“I believe in it.” I lower my voice, as though Gogo and Mama are listening in, even though they’re nowhere around. Since Mama doesn’t believe in things like that and Gogo does, I can’t talk about it without offending somebody.

“Really? Why?”

“I’ve seen some things. And at the end of the day, I couldn’t explain them.”

“Like what?” he asks.

I think about everything that has happened in the last two days—the witch who told me she was coming for me and nothing could stop her, the drunken man who changed into a crocodile and then back into a man right before my very eyes. Did I just dream his sudden transformation? And that’s another thing—the dreams I’ve been having, dreams so real it feels like I exist in two worlds at the same time.

But I don’t know how to tell these stories to anybody else without sounding crazy. So I just shake my head.

“I thought you loved science,” Little Man says. “Aren’t you making the highest marks in biology?”

I nod. “I think it’s interesting to learn about the human body. I like learning about diseases and how people cure them.”

I don’t really know how to explain how I feel about biology—like I belong somehow. It’s as if everything I learn, I already knew, somewhere deep inside, but biology gives me the words I need to talk about it. At the same time, I know there are things it can’t explain about the human body. Maybe that should be a scary thing, but it’s actually comforting. At the end of the day, we still need God.

“But you still believe in witches and ancestors? Scientists say those things don’t exist. So if you love science, how can you believe in those things?”

“I just think there’s a lot science can’t explain,” I say. “Maybe someday we’ll understand how it all fits together, but as for now…no matter how much we know, it’s still a mystery.”

He swipes up my heart with his smile. “That’s what I like about you, Khosi,” he says. “You always say just what you think.”

I wish that was true! Little Man sees me with different eyes than the ones I use to judge myself.

Little Man leans forward and whispers, like we’re in some conspiracy, “Okay, if I was dying, I’d go to the sangoma. What would I have to lose? It might help and it won’t hurt. My gogo swears by it and I love my gogo.”

Somehow I don’t think my gogo would like it if she knew a young man was grinning at me like this. But I’m so glad, I’m bursting. Maybe… maybe…maybe Little Man likes me, too.

“Have you ever heard the joke about the woman who went to see a sangoma because her daughter-in-law had cast an evil spell on her?” he asks.

“No.”

“Yeah, the old lady had been cursed with so much toe jam, her feet were stinking like—whew!—a chicken’s arse.”

Now we’re both laughing. But soon the laughter turns into what-do-I-say-next awkwardness.

Little Man kicks at the dust with his flip-flops.

“Are you watching the Bafana Bafana game?” I ask.

“Sis man, it’s as if you think I’m not South African,” he says. “Of course I’m watching! In fact, I’m missing the game because I came outside to talk to you.”

When he says that, it feels like I’m dropping from the top of a tall building and falling fast towards concrete. I’m reluctant to leave but if he really wants to be watching the game instead…“I can’t stay. I need to go home.”

“I’ll walk you,” he says, quick quick, and my heart leaps again, hurtling forward, fast like a cheetah.

“Oh, I wouldn’t want to keep you from watching the game,” I say, wishing immediately that I hadn’t opened my mouth. Of course, I want him to walk me home. I just don’t want him to feel obligated.

“You live five minutes away,” he says. “I won’t miss much.”

But there’s a bigger problem. “Gogo might be angry if she sees me with a boy.”

“I could put on my mother’s skirt and we could pretend I’m a girl. But Mama’s so much fatter than me, I don’t think it would stay up.” He grins at me. “I’d walk through the streets of Imbali, showing everybody my underwear.”

I can’t help laughing. Little Man is as skinny as a hyena. Who cares if a man is skinny? It’s women that should be nice and fat in order to grow babies.

“Anyway, I’ll see you in school on Monday,” I say, smiling at him. “Bye, Little Man.”

“Bye, Khosi,” he says. He pauses for a second, and then adds, “It was really fun talking to you. Thanks for coming by.”

Oh my God, I’m so happy to hear that! On the way home, I can’t help it—I dance the toyi-toyi, shifting my weight from one foot to the other and shaking my fist in the air. When people see me, they wave their fists in response and call out, “Amandla! Power!”

“Awethu!” I wave back and toyi-toyi, winding my way through the maze of streets that make up Imbali.

The cell phone rings, interrupting my dance. It’s Gogo, wondering where I am.

“I’m coming now now,” I say, hanging up just as somebody grabs me from behind with the crook of his arm.

The cell phone flies through the air and lands in the dirt.

I start screaming.

“Shut up,” the drunk man says, rough, choking me with one arm, forcing all sound back into my throat. He holds me firm against him, his body curving around mine, his fingers brushing against my neck, scaly and cold.

Crocodile skin.

God, please please help me.

I struggle against his arm, kicking at his leg—all the time, gulping at air, the way I imagine I would if I flew up, up, up, so high that oxygen disappears. Black light creeps up over my eyes, blocking the world out, but not before I see his face looming over me as I crash onto the packed dirt road.