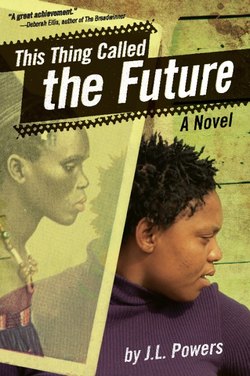

Читать книгу This Thing Called the Future - J.L. Powers - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

NIGHTMARE

A drumbeat wakes me. Ba-Boom. Ba-Boom. It is beating a funeral dirge.

When I was my little sister Zi’s age, we rarely heard those drums. Now they wake me so many Saturdays. It seems somebody is dying all the time. These drums are calling our next-door neighbor, Umnumzana Dudu, to leave this place and join the ancestors where they live, in the earth, the land of the shadows.

I get up and walk to the window, peeking through the curtain at the Dudus’ house in the faint pink light of dawn. Their house is small like ours, government built—a matchbox house made of crumbling cement and peeling peach-colored paint. It is partially obscured by the huge billboard the government put up some few weeks ago between our houses. This is what it announces in bold white lettering against a black background:

THIS YEAR, 100,000 CHILDREN WILL BE BORN WITH HIV!

Gogo, my grandmother, fretted like mad when that billboard went up. “People who can’t read, they will just see that symbol for AIDS right over our house, and they will say, ‘Those people, they are the ones spreading it.’”

I tried to soothe her. “People know better than that. Those billboards are everywhere.” It’s true, the government wants everyone to know about the disease of these days before we all die from it.

But Gogo shook her head. “You watch, we will have bad luck from this thing,” she predicted.

Ba-Boom. Ba-Boom. The drums next door continue and a dog across the street howls in response.

I look for movement in the Dudus’ yard but see nothing.

Like us, they have wrapped thick barbed wire around the top of their fence in order to keep tsotsis away. Only some few of us have anything that tsotsis would steal. But these days, things are so hard those gangsters will hold a gun to your head and steal crumbs of phuthu right out of your mouth even as you are chewing and swallowing.

Ba-Boom. Ba-Boom. Two women, walking down the dirt road that runs in front of our house and balancing heavy bags of mealie-meal on their heads, pause to stare at the Dudus’ house.

I look back at my sleeping family. Zi and Gogo share one bed, low snores erupting from Gogo’s open mouth, revealing reddened gums where her teeth have rotted and fallen out over the years. Mama looks peaceful in the bed that she and I share when she comes home.

During the week, Mama lives in Greytown, where she works as a schoolteacher. She doesn’t make enough money for us to live with her, so she rents a very tiny room there and sends the rest of the money home, which supplements Gogo’s government pension. My baba lives with his mother in Durban, another city an hour away. Unlike Mama, he doesn’t have a good job; there is hardly ever enough money to go see him.

All over South Africa, people struggle. Nobody has enough money. Anyway, we blacks don’t have money. Whites—maybe they are rich, but the rest of us suffer. There are poor whites, it’s true, but not so many as poor blacks.

Even the next door neighbor, Inkosikazi Dudu, she will suffer now that her husband has died. This week, Mama came home from her job some few days early to help with her husband’s insurance settlement. “Yo! it is sad, he left her very little money,” Mama said.

“What is she going to do?” I asked. “How is she going to live?”

“She has six grown children,” Mama said. “They will help her.”

“How?” Gogo asked. “They don’t have any education so they don’t even have good jobs.”

“She is old. She has a government pension,” Mama said.

Gogo clucked her tongue. “It is not enough. I don’t know how we would manage if you did not work. We will have to be very good to her and help her if she needs it.”

Gogo is always generous with what little we have. “If we don’t help others, what will happen to us when we are the ones needing help?” she asks.

Ba-boom. Ba-boom. I can’t believe my family is sleeping through the racket.

To me, the drumbeat is foreboding. After my uncle Jabulani died, my baba’s family was almost torn apart by the accusations until they called a sangoma in. She consulted the ancestors and told them that in this case, there had been no witchcraft, only the disease of these days. “It is just the sadness of today,” she said, “that the young people are dying and leaving their children without parents.”

“Leave the curtain and come back to bed, Khosi,” Mama murmurs. She pulls back the covers and pats the space beside her.

“The beating of the drums woke me,” I say. “Can’t you hear it?”

“It’s too much early,” Mama replies, yawning loud.

“It’s a funeral and you know what that means,” I say. “Trouble.”

“He was an old man and ready to die, Khosi,” she says. “Nobody is going to say his death was this thing of witchcraft. It isn’t like all these young people dying before it is their time. That is what worries everybody.”

It’s true, what she says. When a young person dies, it is because their spirit was taken from them. But an old man’s death is natural and nothing to fear. He has lived his life and it is time for him to become an ancestor, to help his descendants through life.

“Woza, Khosi,” Mama says again.

So I let the curtain fall and crawl back into bed. Mama puts her arm around me and I cuddle up into her fat cocoa-brown warmth.

Her orange headscarf tickles my forehead as I drift back into the world of dreams, the drumbeat troubling me even in sleep. This one is a white dream, the color of the moon in the afternoon sky, so I know the ancestors sent it to me.

I’m sitting in hospital with Mama. Her skin is weeping underneath a white bandage. “They’re going to remove the burnt skin,” she explains when I wonder why we’re here, especially when I see all the bodies of dead people piled up in the corner.

We wait for a long time and finally they call her into a small room. The nurse comes to remove Mama’s bandages, her gloves bloody from the last patient.

Mama jerks her arm away. “No, Sisi, I do not want you to do this until you change your gloves.”

The nurse crosses her arms. “Listen here, I have been working at this hospital for fifteen years. Are you going to tell me how to do my job?”

“That last man you treated could have AIDS,” Mama says.

The nurse storms out of the room. Mama takes the nurse’s instruments and begins to scrape the dead skin off. “You see, this is why we need good nurses in South Africa,” she tells me. “Otherwise, they just do this thing of spreading HIV.”

The dream changes and now we’re sitting in church as the collection plate is being passed around. When it reaches us, Zi carefully places the five rands that Gogo gave her in the plate, looking proud and happy that she’s giving to the church.

I pass the collection plate to Mama and watch as she starts to put a twenty rand note inside, then stops, clutching the money before passing the plate on by.

“Mama?” I whisper, surprised. Mama always gives to the church. It is our duty and obligation as Christians, she has always said. If we fail to give to the church, which feeds our souls, it is stealing from God.

“Hush, Khosi, we need it to pay the medical bills,” Mama says, and I notice that her bandage is bloody and weeping a thick yellow substance. She sees the look on my face. “It is just a little thing, Khosi,” she says. “God understands we need the money.”

I wake, a taste in my mouth that comes only after dreaming. And my shoulders ache, like I have been lifting heavy bags all night long.

I know that dreams are not exactly what they seem. But I also know that to dream is to see the truth at night. You may think one thing during the day, but find out it’s a lie when you dream. Sangomas hear the voices of the ancestors all the time, but night is when their spirits speak to all of us, even we regular folks.

What are the ancestors trying to tell me?