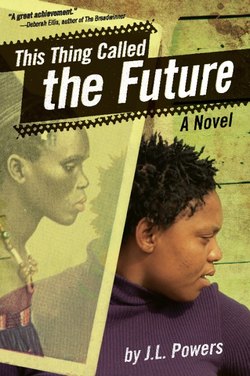

Читать книгу This Thing Called the Future - J.L. Powers - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER EIGHT

THE LIGHTNING BIRD

I tell Gogo all about the sangoma visit as we take Mama’s freshly washed clothes off the line in the backyard. The air is growing hot and heavy with rain that wants to fall but doesn’t.

“Khosi, why does it rain?” Zi asks, interrupting my conversation with Gogo. She’s tracing the cracks in the cement with her fingers.

“You see, the sky is a man,” I say. “And the earth is a woman. When it rains, he’s sending his seed to the earth, so the earth can give birth to all the plants that feed us.”

“So the sky and the earth are married?” Zi screws up her face at me.

I laugh with her. “Yes. And when the sky is angry with his wife for something she said, he punishes her by withholding his seed. And then the earth grows cracked and dry and infertile and pleads with her husband, ‘I am a foolish woman, with a terrible temper. Please forgive me and send rain so I can be fertile and beautiful once again.’”

We hear the distant rumbles of thunder. It worries me. We never have lightning storms this time of year.

“And thunder?” Zi asks. “Why does it thunder?”

“Even God above has this thing of anger,” Gogo says as we hurry inside with the last basket of clothes.

Auntie Phumzile and her girls arrive just as I fold the last skirt. “You’re lucky we finished so you don’t have to help,” I tell my cousin Beauty.

Mama comes out of the bedroom and everybody crowds into the dining room. Beauty and I go into the kitchen to cook phuthu and beef—a treat that Auntie has brought—and Beauty tells me all the secrets she’s saved up since last week.

“I have a boyfriend,” she giggles.

“Izzit?” It seems sometimes that the whole world has a boyfriend, except me. I just want one, that’s all. “Does Auntie know?”

The look she gives me makes me feel stupid. Of course, Auntie’s just as ignorant about Beauty’s boyfriend as Mama is about Little Man.

“I like someone too,” I confide, looking at the carrots I’m chopping instead of looking at Beauty.

“Does he know you like him?” Beauty asks

“He must,” I say. “I don’t think I hide it very well.”

“Shame. You shouldn’t let a man know you like him, not until he asks you out.” When Beauty shakes her head at me, her long lovely plaits linger on her shoulders, caressing her before they tumble down her back.

My own hair is just little tufts of curls sprouting all over my head like new plants shooting up through soil. We have the extensions, but nobody has time to plait my hair.

“Beauty, will you plait my hair today?” I ask. Maybe Little Man will notice if I come to school tomorrow with a new weave. Hair is important to him—it’s taken him four years to grow his dreads.

“Of course,” she says. Then she adds, as if she knows so much more than I do, “Men really like it when you have plaits in your hair. You watch, Khosi, this boy you like will tell you just what he thinks when you come to school tomorrow.”

“I hope so.”

After we eat, we crowd into the sitting room watching Generations, our favorite soapie. I sit on a chair and Beauty begins to work on my hair, tugging and pulling at each tuft to add the extensions. My scalp is already beginning to itch and she hasn’t even finished yet.

Halfway through Generations, the electric storm begins. First the TV crackles and the picture dies. Then the entire room lights up in black and white contrast, so that when I look at the faces of my family sitting opposite me, they are pale, pasty white, like they no longer belong to the living.

Zi squeals and runs to hide in the bedroom. The two younger girls, Beauty’s little sisters, join her. Gogo’s hands tremble as she totters to the back room, where the three girls are huddled together under the covers, on the bed Zi shares with Gogo. I used to do the same thing when I was Zi’s age.

“What is this, a freak lightning storm?” Mama asks.

“I don’t think it’s safe for you to leave just yet,” she tells Auntie.

“No, I’ll wait until this passes,” Auntie answers.

Mama steps over to the door and opens it. “Khosi.” She gestures for me to join her. “Come watch this thing, God having a temper tantrum.”

Because it’s Mama, I swallow my fear. We stand together, watching as lightning strikes the ground like the tongue of an angry woman.

“Even though it’s dangerous, there’s something beautiful about it,” I say. Even the fact that a witch can control lightning, using it to kill somebody, doesn’t change how beautiful it is, the way it lights up the whole world in a sea of black and white light.

“It’s like the ocean,” Mama agrees. “Powerful.”

I shiver. Mama puts her arm around my shoulder.

Auntie’s voice echoes from the back bedroom, where she’s busy chiding the little girls. “How can you be frightened by such a little thing as this? A lightning storm? And Mama, you should be ashamed, encouraging it!”

“She sounds just like you, Mama,” I say.

“Neither one of us wants our daughters to be crippled by superstition.”

“Do you really think Gogo is so superstitious?” I ask, knowing what her answer will be, wondering what she would think if she knew that, every night, I leave food and drink out for the ancestors.

This is what I think: Both Gogo and Mama are right, and they’re also both wrong. Science is important. So are the old ways. We can explain some things through science but not everything. But because Gogo and Mama are so stubborn, it makes it really difficult to navigate a path between them, to be my own person, to assert myself. I don’t want to offend either one of them. No, I want them both to be pleased with the person I become. That’s the difficulty of my life.

But Mama surprises me. “Sometimes, even I believe things that aren’t true.” She laughs a little. “So perhaps I shouldn’t judge your grandmother so harshly. Everybody has their own little superstition, heh, Khosi?”

It’s not exactly a concession, but it’s more than she’s ever offered before.

We turn back to the open door, watching the play of light and dark dancing along the horizon.

It’s so rare that we can be together like this, Mama and me. I stand there as long as she does, watching the sky light up with blue and white streaks of light before we close the door, then turn back to Beauty, who’s waiting to finish plaiting my hair.

In my dreams that night, a bolt of lightning creeps into the house, sneaking in through the crack in the door. It knows my name, spoken by the witch. It skulks down the hallway, feeling from side to side, searching… searching…searching for me.

I wake up, bathed in sweat and unable to fall back to sleep. So I get up early to fix Mama a good breakfast before she leaves for Greytown.

While Mama bathes, I cook eggs and toast bread, placing them under a plate to keep warm. I even fry a small piece of fish I saved just for her sending-away breakfast.

But when I open the back door to empty the rubbish bin, there’s a sudden fluttering of black wings, gigantic wings, wings as tall as I am. A man-sized bird. The wings flutter and flash, silver like lightning, quickly disappearing around the corner.

I run around the house, flinging rubbish to the side in my haste, but the bird is long gone, leaving only a streak of something like smoke lingering in the air.

It’s nothing. That’s what I tell myself as I pick up rubbish and place it back in the bin. It’s nothing. At least, that’s what Mama would say. She would laugh. “Sho, it is just a bird, Khosi. You’re scared of a little thing like that? A bird?”

And I would have to admit, “It wasn’t just any old bird. It was the impundulu.” I’d feel stupid telling Mama that. She’d insist it couldn’t be true. I can hear her already, in my head. “Khosi, really! There’s no such thing as a lightning bird. It’s just something old people talk about. A folk tale, nothing more.”