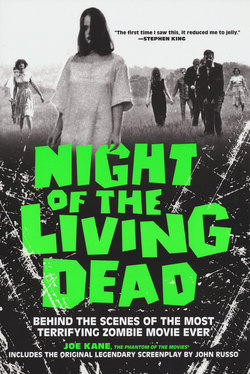

Читать книгу Night Of The Living Dead: - Joe Kane - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 ANCESTORS OF THE LIVING DEAD

ОглавлениеI didn’t mean to invent the new zombies. I never called them zombies. They were those big-eyed cats in the Caribbean.

—George Romero, Zombie Mania

Don’t say that living dead stuff, boss. I’m one of the living living. But you give me the feeling that if I stay around here, I’m gonna be one of the dead dead.

—Nick O’Demus, Zombies on Broadway

The living dead didn’t suddenly spring forth, fully formed and famished, in 1960s Pittsburgh. On the contrary, they have been with us, in one incarnation or another, nearly as long as life itself. Of Western Civ’s five cornerstone pop-culture creatures—Dracula and vampires, the Frankenstein Monster, the Mummy, zombies, and werewolves—all save the last mentioned, technically, fit into the living dead category. The concept of the zombie represents the newest of the group, initially popularized by sensationalist travel writer William Seabrook, the print equivalent of jungle explorers Martin and Osa Johnson, whose lurid, often casually racist and generally xenophobic celluloid safaris (e.g., Baboona, Congorilla) flourished on 1920s and ’30s screens. Seabrook’s influential 1929 book The Magic Island told of deceased Haitians, frequently victims of voodoo vengeance, taken from their graves and forced to toil as slaves for their rapacious re-animators.

At the time, Universal Pictures ruled as Hollywood’s unchallenged fright-film frontrunner. The studio even surpassed Lon Chaney’s fabled silent reign as Gaston Leroux’s Phantom of the Opera (1925) and Victor Hugo’s Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), among other fantastic characters, by bringing Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to the sound screen in 1931, The Mummy the following year, and introducing two new terror titans to replace the by then late Lon—Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi. But it was the independent Halperin brothers, director Victor and producer Edward, who surprisingly beat that mighty Tinseltown outfit to the zombie punch with their classic and trendsetting White Zombie in 1932.

The film adheres fairly closely to the zombie rules set forth in Seabrook’s book. In this creepy shocker, Dracula alum Bela Lugosi cuts a memorably menacing figure as evil-eyed zombie master “Murder” Legendre. He employs a powerful powder to reduce the living to a catatonic state (a fate that befalls drugged ingénue Madge Bellamy) and keep revived corpses obediently working in his sugar mill: The sight of those eerie, dull-eyed drones endlessly pushing the creaking mill wheel remains one of the most indelible images in the whole of horror-film history. Unlike George Romero’s future living dead to come, these early zombies function with no will of their own, killing only on command from their human overseers.

The Halperins struck out in their second undead at-bat with the insufferably dull Revolt of the Zombies (1936), a tale nominally about living-dead troops on the loose in World War I Cambodia—but mostly a static yakathon shot on a few cheap sets. Far more frightening are the ghostly war dead who rise to trouble the conscience of a self-destructive humanity in Abel Gance’s dark World War I fable J’accuse! (1938). Fear-film fans also fared better with a pair of back-from-the-grave Boris Karloff shockers, 1936’s The Walking Dead (wherein Karloff sports a tonsorial style to rival his striking The Black Cat look) and 1939’s The Man They Could Not Hang. In each, Karloff’s reanimated character operates outside then-established OZ (Original Zombie) rules: He can think, act, talk, and, despite a few physical alterations, was not transformed into an entirely new being.

Traditional native zombies received a bit of a boost in the 1940s, resurfacing, to alternately comic and surprisingly scary effect, in the Bob Hope frightcom hit, set in Cuba, The Ghost Breakers (1940). The following year witnessed the release of Monogram Pictures’ Mantan Moreland showcase King of the Zombies. Although later maligned for being politically incorrect, it highlights the inventive African-American comic’s oft-improv’d interactions with the titular living dead. The subject was played solely for laughs in Zombies on Broadway (1945), a fitfully funny vehicle for Abbott and Costello wannabes Alan Carney and Wally Brown, with a major assist from Bela Lugosi as an unstable (what else?) scientist. Elsewhere, the deceptively titled Valley of the Zombies (1946) offered only one eccentric, vampire-like living-dead fellow (Ian Keith).

Probably the first screen zombies to resemble Romero’s ghouls can be briefly glimpsed staggering, arms outstretched, in the 1942 Lugosi vehicle Bowery at Midnight (“They’re coming to get you, Bela!”). Unfortunately, these creepy Caucasian apparitions are granted criminally scant screentime in a largely crime-centric caper. And on the subject of ethnicity, mad scientist John Carradine may have been the first to integrate the homegrown zombie ranks in 1943’s Revenge of the Zombies. In this film undead Anglos and African-Americans un-live together in apparent blank-brained harmony, bringing to mind TV horror host and once and future “Cool Ghoul” Zacherley’s immortal line: “One day we’ll all be dead; then we’ll finally have something in common.” Rather passive voodoo-struck female zombies, meanwhile, supply the supernatural angle in 1944’s Voodoo Man, wherein Monogram springs for three top terror talents—Bela, Carradine, and the drolly sinister George Zucco.

“One day we’ll all be dead; then we’ll finally have something in common.”

—Zacherley

Zucco scores solo lead honors in the second-best zombie movie of 1943, The Mad Ghoul. This ingenious, wryly scripted (by Paul Gangelin, Hans Kraly, and Brenda Weisberg) scarefest details the adventures of one Dr. Morris (Zucco) who, assisted by a clean-cut, All-American boy med student named Ted (David Bruce), works on a series of seemingly harmless experiments. Little does the ever innocent Ted realize, however, that the doc is actually planning to create slaves to do his ruthless bidding by perfecting a gas designed to induce zombie-like trances. Soon Ted is led by Dr. Morris on nocturnal graveyard visits, where he practices his surgical techniques, removing the hearts from recently buried cadavers in order to sustain his own increasingly worthless life. The Mad Ghoul’s mix of genuinely creepy over-the-top horror and deadpan gallows humor qualifies it as one of the era’s best and brightest fright flicks.

Even The Mad Ghoul, however, pales beside RKO producer Val Lewton’s and director Jacques Tourneur’s atmospheric masterpiece of quiet horror I Walked with a Zombie (1943). An extremely fetching Frances Dee plays a Canadian nurse assigned to care for Christine Gordon, the comatose wife of plantation owner Tom Conway, on the gloomy Caribbean isle of San Sebastian. Here, locals “cry when a child is born and make merry at a burial.” Is Gordon really a zombie, victim of a voodoo curse? Finding the answer to that question provides viewers with one of horrordom’s most haunting cinematic journeys.

In the 1950s, the zombie took a cinematic backseat to radioactive mutants and hostile E.T.s, though exceptions proved the rule in the Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis romp Scared Stiff (1953), a retooled Ghost Breakers. The largely dull Boris vehicle Voodoo Island, the static, subaqueous The Zombies of Mora Tau (1957), and bargain-basement schlockmeister Jerry Warren’s Teenage Zombies (1959), which was the first flick to feature a zombified ape, as well as your typically overage titular adolescents, brain-zapped to serve as Stateside pawns of the International Commie Conspiracy.

Teenage Zombies (1959), was the first flick to feature a zombified ape.

Ed Wood’s deathless Plan 9 from Outer Space (1956, unreleased until 1959), is justly lauded in many circles (including this one) as the best bad movie ever made. It merged zombies with a more contemporary trauma, the ever-present alien threat. While slow to implement (to put it mildly), the invaders’ insidious scheme calls for the resurrection of the deceased via “long-distance electrodes shot into the pineal and pituitary glands of the recent dead.” As dedicated Edheads know, the interlopers manage to re-animate all of three zombies—played by slinky erstwhile horror hostess Vampira (a.k.a. Maila Nurmi), massive Swedish wrestler and Ed repertory troupe regular Tor Johnson, and chronically underrated chiropractor Tom Mason, subbing for the actually, inconveniently dead Bela Lugosi. The group ambulates in a manner much like Romero’s future living dead.

The lobotomy-scarred Creature with the Atom Brain (there are actually several in number) were scientifically revived corpses in the service of a crazed ex-Nazi (Gregory Gay), in league with a deported gangster (Michael Granger) who’s looking to rain vengeance down upon his enemies. While lacking Night’s zombie autonomy, these are possibly the most violent and arguably the scariest deaders seen onscreen to that point (1955). They’re capable of snapping human spines and, with the help of those handy atom brains, even blowing up stock-footage airplanes.

Edward L. Cahn’s cheap but occasionally chilling Invisible Invaders sees transparent aliens commandeer earthly cadavers for the usual sinister purposes. Of all the ’50s zombies, these most closely resemble those in Night of the Living Dead. They don’t boast the latter’s age, gender, and occupational variety—all are business-suited, middle-aged white guys who look like they suffered simultaneous seizures at the same sales convention. But they’re honestly unnerving dudes for 1959 as they stagger in stiff, hollow-eyed tandem down a cemetery hillside.

Kicking off the next decade, 1960’s Cape Canaveral Monsters repeats Invisible Invaders’ riff of aliens reanimating and inhabiting expired Earthlings, in this case bodies retrieved from a car crash. An admirably nihilistic ending supplies the lone attribute of this shoestring sci-fi effort by director Phil Tucker, who fails to recapture his Robot Monster (1953) magic. Another notoriously penurious entrepreneur, minimalist sleaze merchant Barry (The Beast That Killed Women) Mahon, went the traditional voodoo route with his obscure New Orleans-set outing The Dead One (1961). It’s the first Stateside zombie movie lensed in color, the better to accentuate the pale white title character’s sickly green visage. Connecticut-based auteur Del (The Horror of Party Beach) Tenney headed south to the Caribbean, by way of Miami Beach, to create the nearly thrill-less black-and-white zombie quickie Voodoo Blood Bath (1964). A.k.a. Zombie, the film wouldn’t widely surface until 1971 when aptly named distributor Jerry Gross resurrected it as the cheatingly titled I Eat Your Skin. The film doubled up with his much more explicit I Drink Your Blood, a blatant bid to ride Night of the Living Dead’s cult coattails.

AIP produced a more lavish living dead story in Roger Corman’s 1962 Tales of Terror. The Edgar Allan Poe-based trilogy highlighted a reanimated Vincent Price in The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar segment, a tale George Romero would tackle nearly thirty years later in the Dario Argento collaboration Two Evil Eyes. The most creative of the period’s drive-in-targeted active corpse flicks, though, came from Las Vegas and the fertile mind of the late Ray Dennis Steckler. His 1964 The Incredibly Strange Creatures Who Stopped Living and Became Mixed-Up Zombies not only boasted the second-longest title in genre-film history (after Corman’s The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Journey to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent) but arrived as the first zombie musical (in fact, Steckler billed it as the “First Rock’n’Roll Monster Musical”). Del Tenney’s Horror of Party Beach, unleashed earlier that year, actually offered the first zombie rock song, the Del Aires’ “The Zombie Stomp.” The Incredibly Strange Creatures…scores more points with its wildly surreal, pre-psychedelic extended-nightmare sequences than with its rather uninspired rubber-masked zombies.

Other countries likewise contributed to the screen zombie ranks, often tinkering with traditional zombie rules. Mexico delivered Santo vs. the Zombies (1962), a.k.a. Invasion of the Zombies, pitting that most exalted, eponymous masked wrestler against energetic dead men in the employ of a criminal mastermind. That pic proved popular enough to inspire Santo to join forces with fellow grappler Blue Demon in Santo and Blue Demon Against the Monsters (1968), Santo and Blue Demon in the Land of the Dead (1969), and Invasion of the Dead (1973). Zombies would likewise surface in the Jess Franco-directed French/Spanish co-production Dr. Orloff’s Monster (1965) and Germany’s The Frozen Dead (1966), the latter fleetingly elevated by Nazi scientist Dana Andrews’s death-by-zombie-arms-protruding-through-a-wall. The tableau is similar to the nightmare sequence that opens Romero’s Day of the Dead, though executed with far less flair.

Britain took its zombies a tad more earnestly. Sidney J. Furie’s Dr. Blood’s Coffin (1961) is a slowly paced Frankenstein-like affair, while the bleak doomsday quickie The Earth Dies Screaming (1965) offers some atmospheric shots of terminated townsfolk raised (once again) by alien invaders. The Hammer period piece The Plague of the Zombies (1966) represents the first film to show ghouls rotting before viewers’ eyes (unless you count Vincent Price’s famous facial meltdown in the earlier cited Tales of Terror).

Plague of the Zombies (1966) represents the first film to show ghouls rotting before viewers’ eyes.

It might be argued that Herk Harvey’s brilliantly terrifying art-house horror Carnival of Souls (1961)—with its relentless nightmare quality and haunting nocturnal images of zombie-like phantoms in perpetual pursuit of alienated heroine Candace Hilligoss, in a movie created by the operators of a Lawrence, Kansas, commercial/industrial film house—served both as Night of the Living Dead’s spiritual progenitor and basic business model. But the film that acted as its true template was the 1964 American-Italian co-production The Last Man on Earth. Based on Richard Matheson’s celebrated doomsday novel I Am Legend (also the inspiration for the 2007 Will Smith blockbuster of the same name as well as the 1971 Charlton Heston showcase The Omega Man), The Last Man on Earth arrives replete with slow-moving human corpses-turned-predators, boarded-up windows with the creatures’ hands thrusting through them, an infected child, human bonfires, and many other key elements that would soon surface in Night.

But no matter how groundbreaking the walking dead imagery, even Last Man lacked the insidious black magic that would make Night of the Living Dead the most terrifying and enduring zombie movie ever.

I caught that on television, and I said to myself, “Wait a minute—did they make another version of I Am Legend they didn’t tell me about?” Later on they told me they did it as a homage to I Am Legend, which means, “He gets it for nothin’.” George Romero’s a nice guy, though. I don’t harbor any animosity toward him.

—Richard Matheson on Night of the Living Dead, as told to Tom Weaver