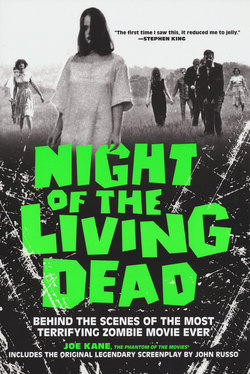

Читать книгу Night Of The Living Dead: - Joe Kane - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4 CASTING A CULT CLASSIC

Оглавление“They’re dead. They’re…all messed up.”

—Sheriff McClelland, Night of the Living Dead

Before filming could begin, Image Ten looked to cast the core characters caught up in the zombie menace. Most crucial was the lead, Ben, who would have to carry much of the movie on his shoulders. As originally written, the character was a resourceful but rough and crude-talking trucker, a role initially envisioned for Rudy Ricci. Those plans changed when a thirty-one-year-old African-American actor named Duane Jones competed for the part.

“A mutual friend of George’s and mine was a woman by the name of Betty Ellen Haughey,” Russ Streiner relates. “She grew up in Pittsburgh, but at that time she was living in New York and she knew of Duane Jones. He’d started off in a suburb just outside of Pittsburgh, yet he was off in New York making a living as a teacher and an actor. And she said to us, when Night of the Living Dead was really developing in preproduction and building steam, ‘You should meet this friend of mine from New York.’ Duane happened to be in Pittsburgh visiting his family for one of the holidays, and we auditioned him. And immediately everyone, including Rudy Ricci, said, ‘Hey, this is the guy that should be Ben.’”

Romero agrees with that recollection: “Duane Jones was the best actor we met to play Ben. If there was a film with a Black actor in it, it usually had a racial theme, like The Defiant Ones. Consciously I resisted writing new dialogue ’cause he happens to be Black. We just shot the script. Perhaps Night of the Living Dead is the first film to have a Black man playing the lead role regardless of, rather than because of, his race.” (Contrary to that opinion, oft-expressed by Romero and others, Jones was not the first black actor to be cast in a non-ethnic-specific starring role; Sidney Poitier earned that distinction in 1965 playing a reporter in James B. Harris’s nuclear sub suspenser The Bedford Incident and, the following year, portraying an ex-military man turned horse-breaker in Ralph Nelson’s western Duel at Diablo, doubly ironic given Duel’s racial theme, albeit one centering on Native-Americans.)

At that, black actors were no strangers to Latent Image ads. “In looking at some of those old [ mid-’60s] commercials,” says Russo, “we always had black actors and we always gave a lot of work to people who had a tough time getting it. That was our nature, so we didn’t blink at casting a black actor in that role.” The slim, handsome Jones was himself quite familiar with aspects of the ad world, having earlier posed as an Ebony magazine model in layouts selling everything from liquor to Listerine.

“We didn’t blink at casting a black actor in that role.”

—John Russo

Still, Russo detected an initial uneasiness. “At first he distrusted those of us on the crew, behind the camera. He wondered why we would cast a black man in the lead role of our movie, and he thought we might be out to exploit him in some way.” Jones quickly overcame any brief initial reluctance he may have had but did not completely separate his ethnicity from the character: “It never occurred to me that I was hired because I was black. But it did occur to me that because I was black, it would give a different historic element to the film.”

While still earthy and capable, Ben acquired an at once intense and understated quality that Jones brought to the role. According to the late Karl Hardman: “His [Ben’s] dialogue was that of a lower-class/uneducated person. Duane Jones was a very well-educated man. He was fluent in a number of languages.” A B.A. graduate of the University of Pittsburgh, Jones had dabbled in writing, painting, and music, studied in Norway and Paris, and was completing an M.A. in Communications at N.Y.U. between Night shoots. “Duane simply refused to do the role as it was written. As I recall, I believe that Duane himself upgraded his own dialogue to reflect how he felt the character should present himself.”

A look at the original script (courtesy of Marilyn Eastman, who’d saved the only known existing copy) demonstrates the difference. When white Ben first arrives at the house, he says to Barbara: “Don’t you mind the creep outside. I can handle him. There’s probably gonna be lots more of ’em. Soons they fin’ out about us. Ahm outa gas. Them pumps over there is locked. Is there food here? Ah get us some grub. Then we beat ’em off and skedaddle. Ah guess you putzed with the phone.”

As translated by Duane Jones, the same speech goes: “Don’t worry about him. I can handle him. Probably be a whole lot more of them when they find out about us. The truck is out of gas. The pump out here is locked—is there a key? We can try to get out of here if we get some gas. Is there a key?” (Ben tries the phone.) “’Spose you’ve tried this. I’ll see if I can find some food.”

Same basic information, but in the original script, white Ben is a stereotype. Via Jones’s interpretation, black Ben is not.

According to soundman Gary Streiner, “Ben was Duane in most every way. Duane was very intelligent, thorough, and professional. If he wasn’t on camera, he was running his lines or just plain reading. Duane was not chatting people up when not working, but you were never waiting on Duane because he didn’t know his lines. I think he adopted his interpretation of Ben in the casting session and for evermore was the holder of the character.”

Hardman approved of Jones’s approach and adjusted his own performance accordingly. “Duane played the character so calmly that it was decided I should play Harry Cooper [Harry “Tinsdale” in the original script] in a frenetic fashion with fist-clenching and that sort of thing, for contrast. There was absolutely no working up into character. Harry Cooper started up with a hardass attitude, and he did not deviate one iota.”

Jones also contributed what proved to be an important component in perfect synch with the zeitgeist, an element vital to the film’s runaway success: black rage. In that pre-“blaxploitation” era, Jones’s Ben emerged as a cross between contemporaneous characters in a Sidney Poitier vein (e.g., In the Heat of the Night’s Virgil Tibbs, Lilies of the Fields’ Homer Smith) and the edgier African-American protags, like Richard Roundtree (Shaft) and Ron O’Neal (Superfly), who would soon change forever the image of black men on screen. While he earned audience support, Jones’s Ben made for an unusually harsh “hero,” even shooting an unarmed Harry Cooper in cold blood (though it would be hard to say he didn’t deserve it).

But that was a large part of the point: Ben wasn’t a hero. He was an average guy, an everyman of any ethnic stripe, who simply reacted to an irrational situation with strong survival instincts and a competence that, though far from infallible, surpassed that of his five adult companions trapped in that zombie-besieged farmhouse.

Since Ben’s character was written sans a specific ethnicity, there’s never any overt reference to race in the film—not even in those heated shouting matches between Ben and Harry (though one senses the ever-seething Harry’s unvoiced bigotry). Yet the character’s black identity undeniably adds another layer of anger to the pair’s ferocious battles for alpha-dog status. Ben’s blackness also lent greater tension to his relationship with the alternately comatose and hysterical Barbara. As Russ Streiner admits, “We knew that there would probably be a bit of controversy, just from the fact that an African-American man and a white woman are holed up in a farmhouse.” When Barbara claws at her clothes, citing the house’s unbearable heat, the scene suggests a subtext of sexual repression and fear. John Russo points out: “And then she falls into his arms. And I know that a lot of the bigots in the country are going to be thinking, ‘Oh my God, now what’s he going to do? He’s got this white woman in his arms,’ and lays her down on the couch and he unfastens her coat…and so I was aware that it might have those kind of vibes.”

A panicky Barbara then angrily lashes out. “It was written in the script that Barbara was to smack Ben at least three times,” says actress Judith O’Dea. “But this was a very sensitive issue for Duane Jones at that time and he said, ‘I can accept being smacked once. But I don’t want to play it the way that you’ve written it.’ It was rewritten…I gave him a smack. And he gave me the fist—right in the face.” When Ben punches Barbara, a white woman—this before Poitier’s groundbreaking smack of a racist aristocrat (Larry Gates) in In the Heat of the Night—that act supplied another envelope-pushing note to the proceedings. Those scenes provoked palpable reactions in audiences of the day.

Jones himself had opposed the punch, rejecting the idea that Ben would behave in so violent a manner. Russo concurs with that evaluation, “It really is out of character for him to hit her, but we needed him to because we had to get her unconscious for the sake of the plot. The truck driver, the other character, would have hit her.”

Jones, in general, proved notably nonviolent. Says Romero: “He hated any kind of firearm—he really hated that gun. So we had to have somebody hand it to him. It had to be taken from him right after. He had to take one of the boards off the wall and he hit my camera. He couldn’t work for like an hour!”

Jones received on-the-job gun training from jack-of-all-trades Lee Hartman, who did quadruple duty as a background reporter in the newsroom scenes, a funeral-suited zombie, and a posse member: “Duane Jones never shot a rifle before, so I let him have mine. I said, ‘Keep it against your shoulder.’ It was a 30–30 rifle. ‘Aim it at the bottom of that tree there.’ He was aiming at the top. ‘It’s gonna go a mile and a half if you miss it.’ He had a real bullet in there; we didn’t have any blanks.” Despite his antipathy toward weapons, Jones quickly got the hang of it.

One thing the actor consistently did not want to back down from was his character’s color. “Duane actually thought we should take note of it,” says Romero. “Now I think we probably should have. Not to make it a big point, but to refer to it at least. We had written this guy as angry for no reason at all. But that automatic rage that comes out, that would have been an interesting overlay. Duane was the only one who knew this.” Romero also allowed that if they had consciously played the race card, the results might have been heavy-handed, disrupting Night’s delicate balance.

At one point, when the filmmakers considered lensing an alternate ending that would permit Ben to survive, it was again Duane Jones who stood firm. “I convinced George that the black community would rather see me dead than saved, after all that had gone on, in a corny and symbolically confusing way.” Besides, said Jones, “The heroes never die in American movies. The jolt of that and the double jolt of the hero figure being black seemed like a double-barreled whammy.”

Many audiences perceived the parallel between America’s increasingly violent civil rights struggles—particularly, the then-recent assassination of Martin Luther King by racist hitman James Earl Ray, with the suspected cooperation of the FBI—and Ben’s execution at the guns of the redneck posse at film’s end. Without a black actor in the lead, Night would still have been an innovative shocker but wouldn’t have hit the cultural nerves it did.

In 1987, shortly before his premature death from heart failure the following year, Jones granted Fangoria journalist Tim Ferrante an extremely rare, exclusive in-depth interview, wherein the actor—who’d largely shunned his association with the cult hit, adopting something of a “Ben there, done that” attitude—revealed his feelings about working on the then-twenty-year-old film: “Even when I wanted people to leave me alone about it, I never regretted that I did it. I remember it as great fun. We worked very hard. There was a wonderful feeling of camaraderie and good humor and goodwill. They were very considerate people to work for. You never felt that you were being abused or misused. They used to have to drive me back to my parents’ home, all the way out to Duquesne, every night. Jack Russo, usually. He never did that begrudgingly. They were wonderful folks to work for. They really were.”

Jones owned up to having problems with many critics’ perception of the film. “The thing that used to bother me the most was that interviewers just assumed that we were a bunch of amateur actors. It was an interesting mix of amateurs and professional actors, which was even more clever on George’s part.” Jones also had high praise for the filmmaking approach. “The best storytelling in the world goes on in commercials. So there was that cleanliness and very sharp editorial eye that went into it. Internally, in the film itself, they captured somehow an independent aura. If you really look at it technically, it was most professionally done.”

In that same interview, Jones conjured a rare sour moment, a negative incident that had haunted him for two decades. “I guess because everything was so pleasant that one of the things that sticks out in my mind is a moment that was strangely unpleasant. There was a point where George and the crew were planning a shot and setting up. It was getting to be late afternoon, evening, and this magnificent butterfly wandered into the house. I remember clearly that it landed on the far wall. And to a person, every single one of us stopped what we were doing and we were just standing around admiring this beautiful, beautiful creature that had just come in as a spirit among us and attached itself to the wall. Soon it was time to get started and someone thought that his idea of a joke would be to come and smash the butterfly. I remember the stunned silence of the group, and the visceral reaction of wanting to regurgitate was just so real that that moment sticks out in my mind that it was out of synch with everything. Nobody could believe that he had done that to us—and to the butterfly. I don’t think we ever quite convinced him that it was a horrible thing to do.”

Though Jones would go on to appear in several subsequent regional and New York City films—most notably as an academic vampire opposite Marlene Clark in Bill Gunn’s 1973 cult fave Ganja and Hess (“another underground classic,” Jones once stated, “one of the most beautifully shot films of that period”)—Hollywood didn’t come calling. Nor were any other Night players summoned. Jones had his own theory on that subject. “For whatever reasons, the reality of who we were in the first place was never clear. Critics assumed we were all a group of amateurs from Pittsburgh. The so-called ‘amateur’ they decided to bestow professionalism on was George Romero. I would never for one second begrudge George any of his acclaim and fame. But some of us could have used another kind of boost to our career, whereas nobody ever assumed we were actors or professionals in the first place.”

Instead of pursuing a West Coast film avenue, Jones followed his first loves, devoting most of his professional life to the theater and teaching, separated, for the most part, from his Ben persona: “I was teaching at N.Y.U. and I used to walk past the Waverly—I used to get out of the subway there—and it showed at the Waverly at midnight for years. One time I was with a group of acting students after class. We were sitting in a restaurant in Manhattan. And it was getting on into the Halloween season and two of the kids were sitting across the table from me and I looked up at the television and realized that the movie being shown was Night of the Living Dead. So I glanced at it for a moment and we went on talking. I kept glancing at it too often because eventually they followed my eyes to see what I was looking at and they looked at the television. And they did not recognize that it was me. Then, when one of the students did identify that that was me, the other two argued that it was not. So we left it at that and went on talking. One said, ‘What ever happened to him?’ I was sitting across the table from him!”

Ferrante fondly recalls his meeting with Duane Jones. “The moment he spoke you just knew he was a special human being. You suddenly forgot he portrayed Ben; he was far too interesting in many other ways. He was gracious, fiercely intelligent, funny, charming, respectful…it was impossible not to like him.” Jones had zero interest in exploiting his cult rep. “It was his practice to not draw attention to himself,” Ferrante explains. “He wasn’t going to live in a world that forever identified ‘Duane Jones’ as the star of Night of the Living Dead and nothing else. He wasn’t arrogant about it, though. He certainly recognized the power of the movie and his role in it, but he was too gifted an intellectual to permit that kind of societal typecasting. I remember pointing out that millions of people loved him in that role; his withdrawal from it wouldn’t make that go away. He appreciated and understood it and was somewhat grateful, but such singular adoration wasn’t a necessary ingredient in his life. He expected people to recognize him as a person and not as Ben, which they did because that’s how he carried himself. He had class. Besides, he was such an arresting man. Night was a mere sliver of his life.”

Jones’s Night cohorts felt the same way. Judith Ridley recalls, “Duane was the only black man on the shoot and perhaps he was feeling a little out of place. He’d always bury his head in a book; he was always reading. But you did really admire him—he was a very classy person.” Gary Streiner holds a similar impression. “I really liked Duane but I didn’t get to the point of friendship with him as I did as with lots of the others.” Says a grateful John Russo, “I doubt that our movie would have been a success without him. His screen presence was one of the key ingredients that helped lift that low-budget pipe dream up by its bootstraps and make it into something that it almost had no right to be. The dream became reality, partly because of Duane Jones.”

“I doubt that our movie would have been a success without Duane Jones.”

—John Russo

With Ben present and accounted for, other key roles went to a variety of Latent Image cohorts. For Barbara, Romero originally wanted Betty Aberlin—“Lady Aberlin” on the Pittsburgh-based Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, for whom The Latent Image had occasionally labored—but a perhaps overprotective Fred Rogers discouraged her from appearing in a horror film. The part went instead to Judith O’Dea, a twenty-three-year-old actress and voice-over specialist who had been working in regional theater since the age of 15 and had recently returned to the Steel City after a stint in L.A., where she’d been trying to break into the Hollywood acting ranks. “I had been there a short while when Karl called and said we’re gonna make a movie. It changed my life. It was exciting. It was where I wanted to be. Anything that came my way, whether it was long hours, whether it was waiting two months to go back and readdress a scene that was already done, didn’t bother me. I loved doing it.”

O’Dea also enjoyed working with Romero. “George would describe what he was trying to achieve in each scene—plot progression, emotion, and so on—then let me ‘go at it.’ Barbara evolved every time we shot a scene.” And Romero allowed for ad-libbing when the situation called for it. Says O’Dea, “The one section I can recall specifically is when Ben tells Barbara what happened to him, and then she explains what happened to her and her brother. For me, that was all ad-lib. I had read the script, but then we just, basically, went by the seat of our pants.” She adds, “That scene was done fine on the first take. I had really gotten into it. I can remember crying like a fiend when they filmed me talking about Johnny. But something went wrong with the sound recorder, or so they had thought. We did shoot it again, but they later found out that the first take was okay.”

O’Dea credits the cast and crew’s earnest approach with putting the story over. “When we were shooting, we wanted it to be as real as possible. I know that many of us really did go through a lot of that emotion and terror making it. It wasn’t done with tongue in cheek. It was done very seriously.” And O’Dea had the literal scars to prove it. “[Duane] never made contact with my chin. But he sure put black and blue marks on my arms where he grabbed me during that fight scene. I didn’t realize till I got home how black and blue they were.” But the filmmakers saved her scariest moments for last. “Barbara’s death sequence was an extremely frightening thing to film—being pulled out amongst all those people.”

Russo feels fortunate that an actress of O’Dea’s caliber was available for the role: “Judy O’Dea brought a tremendous energy to her part in the movie. The way she ran, you really believe her life’s in danger, the way she’s terrified and so on.”

Regarding Barbara’s oft-criticized “helpless” behavior, O’Dea maintains, “I believe Barbara exemplifies honesty. How she got through her horror ordeal is probably the way many real people would…. When the zombies were breaking into the house, she snapped back into reality. It was time to fight back. And she did, until her death. If Barbara is remembered for her honest behavior in the ‘evolution of women in horror’ then I’ll be thrilled.”

Today O’Dea notes: “I believe everyone was too much involved with the ‘present’ and all its challenges to think that movie magic was being made. I honestly had no idea it would have such lasting impact on our culture. People treat you differently. [I’m] hohum Judy O’Dea until they realize [I’m] Barbara from Night of the Living Dead. All of a sudden [I’m] not so hohum anymore. I’ve had several decades of families come up to me and say, ‘You scared me to death when I was a little kid.’ The first thing out of my mouth is, ‘Oh, I’m so sorry’…And then I stop myself and say, ‘Well, I guess that’s what we were supposed to do.’”

“I believe everyone was too much involved with the ‘present’ and all its challenges to think that movie magic was being made.”

—Judith O’Dea

In addition to working at The Latent Image, Russ Streiner had been an actor at the Pittsburgh Playhouse, so he seemed a natural to play Barbara’s bored, mocking brother, Johnny. Besides, as Russo points out, “Russ kind of got pressed into service because we could save money by casting ourselves in various roles.”

As for Johnny’s trademark gloves, Romero explains, “Since Russ was not Robert Redford, we figured that we would need some way to recognize him and that’s why we used the driving gloves, to recognize him later when he returns from the dead.” Streiner was very conscious of the props and made sure to milk them to the max. “You might remember me putting on the driving glove in the cemetery. I was being very blatant about it. When I burst in through the door, my hand with the glove slapped on the door jamb in direct view of the audience.” And the nerdy pens poking from Johnny’s shirt pocket? Per Karl Hardman, “We thought he looked like an accountant or CPA and they always have pens in their pockets.”

Johnny’s teasing relationship with Barbara still strikes a chord with modern audiences. “I think underneath it typifies the kind of sibling relationship that a lot of brothers and sisters have,” Russ Streiner interprets the scene’s credibility. “Brothers especially get into taunting and tormenting their younger sisters. And I think that comes through to the fans, and a lot of people comment on it. ‘Oh, that’s how my brother used to treat me,’ and so forth. So I wanted to keep it realistic on that level. That plus the fact that we as actors knew what was coming, we knew that this was going to be the very first onset of the living dead things, and I just wanted to set the stage for the gloomy things to come.”

In fact, the pair’s increasingly juvenile behavior reinforces the film’s dark fairy-tale flavor, as the two young adults regress into a veritable Hansel and Gretel, ripe, edible prey for the creatures of the forest—or the graveyard. “Russ and I had a great time doing that scene,” O’Dea recalls. “It amazed me how it took me back, warp speed, to when I was a little girl visiting the cemetery with my mother. Those visits always scared me…Death scared me back then. So being upset with Johnny in our cemetery scene was pretty easy to do.”

To portray the quarreling Coopers, Harry and Helen, the filmmakers chose close cohorts Karl Hardman (born Karl Hardman Schon) and Marilyn Eastman. In addition to running Hardman Associates, Karl had performed in commercials like The Latent Image’s The Calgon Story and, before that, like Judith O’Dea, had tried his luck in Los Angeles. Karl’s on- and off-screen daughter, Kyra Schon, remembers, “He did study acting out there. He did some theater. But he didn’t get anything permanent, so he moved back to Pittsburgh.” Marilyn Eastman had worked extensively in regional theater as well as TV, performing such varied roles as a live commercials model and weather girl to a lady vampire on local horror host Bill “Chilly Billy” Cardille’s Chiller Theater.

Both Karl and Marilyn were also well-known figures in the Pittsburgh radio orbit, with Hardman logging in several years on a mega-popular comedy show called Cordic and Company, for which he wrote skits and voiced some fifteen characters. The two also recorded and sold routines for radio syndication before that market dried up in the mid-’60s. The highly verbal, versatile pair improvised much of their Night dialogue, with Eastman coining the oft-quoted line, “We may not enjoy living together, but dying together isn’t going to solve anything!”

A receptionist at Hardman Associates, the then-nineteen-year-old Judith Ridley was originally considered for the part of Barbara before being assigned the somewhat less demanding Judy role. Judith O’Dea affirms, “They originally considered Ridley over me because she was a hell of a lot prettier than I was! I have one of those character faces.” In fact, on Night’s iconic original poster, Ridley’s face is weirdly superimposed over O’Dea’s body. But the ultimate casting choice proved the correct one. “I was dreadful when I read for Barbara,” Ridley confesses. “I’d never done any acting. I think they took pity on me. They liked me. They made a little spot for me. But I was not prepared to be Barbara. I couldn’t have done that role.”

Keith Wayne (born Ronald Keith Hartman), cast as Judy’s earnest young beau Tom, was, likewise, completely new to acting, though not to performing—he led the busy local band Ronnie and the Jesters and would later front such musical aggregates as Keith Wayne and the Unyted Brass Works. He spent much of the Night shoot commuting between Pittsburgh and a steady weekend gig in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. Romero, for one, was quite impressed by the lad: “Of all the people in the cast, I thought he was the celebrity. He was the showbiz cat. He was our Frankie Avalon.”

“Of all the people in the cast, I thought he was the celebrity. He was the showbiz cat. He was our Frankie Avalon.”

—George Romero, on Keith Wayne

No Night performer would go on to enjoy a more devoted cult following than 9-year-old killer kiddie Kyra Schon, who commits the most transgressive acts of all in a movie packed with them—she kills her mom and devours her dad (!). She was literally fed up with him. For many ’60s youths and later punks and headbangers who proudly bore her image emblazoned on T-shirts or tattooed on their bodies, Kyra represented the ultimate in rebelliousness. Her only two words of dialogue in the film—“I hurt”—spoke volumes about the failure of her bickering parents and their misguided values—and, by extension, the entire social system—to nurture her.

A schoolteacher today, Kyra looks back fondly at her time as a cannibal kid. “The role had originally been written for a boy but since there was a boy shortage that year, they settled for the nearest young, warm body they could find. That was me. I was already a horror-movie junkie at that point in my life, watching Chiller Theater every Saturday. The Crawling Eye and The Wasp Woman were my favorite movies. I just couldn’t believe my good fortune that I was gonna get to play a little monster and kill people. What could be better?”

Kyra certainly made the most of her limited screen time. “I don’t do a whole lot in the movie! For most of it, I’m lying there on a table, and that was one night. Then there was the struggle with Duane Jones. That was kind of funny. I was sure he was going to miss the couch completely and throw me through the wall. But he didn’t. Then there was the trowel thing…. Shooting the scene wasn’t nearly as dramatic as watching it. I was stabbing into a pillow with the trowel. And then someone was behind me throwing chocolate syrup against the wall to make it look like the blood was splattering. I had a great time doing it. I didn’t feel that way so much when I was really young, because I took a lot of teasing as a result of it. Maybe it was just their way of paying attention. But I never liked being the center of attention.”

“I just couldn’t believe my good fortune that I was gonna get to play a little monster and kill people. What could be better?”

—Kyra Schon

Today Kyra doesn’t shy away from her association with Karen—nor do her students. “[They] always ask me, ‘Which one were you in? Oh, you were in that old black-and-white one!’ And I say, ‘Yeah, the real one.’”

Like most of Night’s participants, Kyra ended up doing double-duty on the film. “I was used as the upstairs body because they needed someone to drag away. I guess of all of the people there, I was probably the smallest.” Still, the most traumatic moment for Kyra occurred watching rather than appearing in the film. “I never liked seeing my father shot and falling down the stairs. It was too much, watching him grapple with that coat rack.”

For the most part, though, the experience proved a childhood high point: “It was fascinating to watch ordinary people transformed into flesh-eating ghouls. I loved seeing zombies stand around the barbecue grills waiting for their hot dogs, zombies smoking cigarettes, zombies driving cars. There was a surreal quality to that scene that could only be truly appreciated by the mind of a child.”

Another key to Image Ten’s successful secondary casting: hiring people to essentially play themselves. William Schallertesque Charles Craig, a radio and TV veteran who’d worked as Alan Freed’s newsman on the pioneering rock deejay’s Moondog Show in Cleveland and served as an actor and writer at Hardman Associates, portrayed the television newscaster who relayed the breaking bad news regarding the ongoing ghoul epidemic.

“It was pure happenstance I was on the scene at that time as an experienced newsman,” Craig later related. He even wrote his own news copy and added a turn as an intestine-chomping zombie. Craig could also be heard as the eponymous character in the local morning radio comedy series The Teahouse of Jason Flake, produced by and featuring Hardman and Eastman.

Similarly, Chiller Theater host and all-around WIIC-TV front-man Bill Cardille agreed to play the television field reporter—and had to wait some twelve hours on-set before his turn arrived, after a full night working at the station. “When you see me in that movie, that’s after no sleep for about two days.”

Local news cameraman Steve Hutsko signed on to appear as Bill’s cameraman. His story is typical of Night’s naturalistic casting. He’d earlier accompanied Cardille to the set to shoot a local TV story about the filming in progress: “We went to the old farmhouse and they were setting up things. That’s how we got involved. Bill Cardille asked me, ‘Do you want to be in the film? I’m gonna be a reporter and they need a cameraman.’”

Hutsko took a week’s vacation to make sure he could fit the filming into his schedule. “[There] didn’t seem like there was a script for anybody,” he recalls. “I never saw one. The director said, ‘When you go on a news assignment, what do you normally do?’ I said, ‘If we got an assignment like this, and we’re out there half a day, you call into the office and let ’em know what’s going on.’ So I told Bill, ‘What if I tell you I’m gonna call the office?’ And he said, ‘Go ahead, Steve.’” The moment plays completely smoothly on screen.

Production manager George Kosana contributed a memorable bit as Sheriff McClelland, ad-libbing his lines, including the deathless, “They’re dead. They’re…all messed up.” (Which ranks right up there with Streiner’s scripted, “They’re coming to get you, Barbara!”) Posse member Vince Survinski, meanwhile, became the unwitting villain of the piece—it was his perfect shot that nailed Ben. “I shot the hero without knowing it,” he later revealed. “I didn’t know what I was shooting at in that scene until I saw the picture. The first time I saw it with an audience of kids at a matinee, I was afraid to leave the theater! I waited until they all left and snuck out a back door!”

Rounding up the requisite zombies posed far less of a challenge than initially anticipated. According to Russo, “We were worried that we did not have enough money to pay a sufficient number of extras. But we got plenty of volunteers, including people from in and around Evans City, who jumped at the chance to be in a movie. We let them be posse members or made them up as ghouls. They were patient and enthusiastic. They gave the movie a ‘real people’ look that probably added to the believability.”

Casting a wide zombie net, Image Ten likewise looked to their immediate peers for assistance. Romero recalls, “We had a company doing commercials and industrial films, so there were a lot of people from the advertising game who all wanted to come out and be zombies.”

Sometimes, the filmmakers resorted to more aggressive recruitment tactics. Evans City cabinet shop owner Ella Mae Smith remembers, “We were sitting in our yard and a car pulled up in front. A girl got out and she said, ‘Hi, we’re from the movie back there that we’re making. How would you and your husband like to be in it?’ And of course my husband said, ‘No.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, I think that that would be lots of fun.’ So I kind of pleaded and begged and he said, ‘Okay, I’ll go back and see what’s going on.’ But we had no idea what the film was about. So we went back and they started putting this goop all over our faces and we were ghouls. I was thrilled to death our names were up there! Maybe it was because they paid us $25.” In all, some 250 zombies showed up for the shoot.

Naturally, those zombies wouldn’t have much impact without a convincing living dead look. Just as she’d once been considered to play Barbara, Judith Ridley had been picked as a possible candidate to apply the greasepaint. “I was asked at Latent Image to take a makeup course,” she remembers. “They thought that in the production work, if I could do the makeup, then that would be one less freelancer that they would have to hire.” After doing a full makeover, complete with false eyelashes, on volunteer John Russo, Ridley surrendered the assignment to Marilyn Eastman.

With another projected prospect, Tom Savini, serving in Vietnam, Eastman, who had done her own makeup as a regional theater actress, now seemed the logical choice, even though her zombie-making approach proved a work in progress. “You’ll see in the beginning everyone looks like a raccoon. Gradually, they got a little more sophisticated.” With the help of a mortician’s friend called derma wax, Eastman says, “We tried to make variations in the wounds and costumes of the flesh-eaters, to indicate that they must have died in the midst of different normal activities. These were supposed to be the recently dead brought back to life.”

Since the zombies had only newly departed this mortal coil, Russo points out, “They, logically, would not be especially decayed or deformed, so this made the makeups easier. I played the part of one of the first zombies we filmed—the Tire Iron Zombie. My idea was that I would have a certain amount of rigor mortis, so I purposely twisted my face out of shape and moved stiffly, albeit with ‘deadly intentions.’”

As for that notorious nude pin-up ghoul who would adorn the movie’s poster (though often wearing airbrushed bra and panties, presumably to discourage the necrophiliac trade), Eastman says, “I just dusted her down with gray makeup to make her look kind of gray and dead.” Russo relates, “We used an artist’s model for this scene. We figured that some of the dead bodies in morgues would have risen, and we wanted to illustrate this point. It was another ‘believability’ factor. We also didn’t mind any word of mouth that might accrue regarding one of the few nudes to appear in horror movies at this time.”

Word of mouth apparently spread quickly—long before the film was completed. According to Judith Ridley, “The night they filmed the nude ghoul, all of Evans City found out about it. They had their lawn chairs set up around the edges of the property. It was funny to see the rest of the zombies trying to keep their eyes elsewhere instead of looking down at the obvious places on the nude one.” Meanwhile, going many of her cohorts one better, Marilyn Eastman did triple-duty on the film, also contributing a cameo as the infamous insecteating zombie.

“It was funny to see the rest of the zombies trying to keep their eyes elsewhere instead of looking down at the obvious places on the nude one.”

—Judith Ridley

What may be most remarkable, in a pre-reality TV/YouTube/and generally camera-savvy culture, is how Night’s zombies are never caught looking at the lens or deviating from their living-dead personas. Gary Streiner attests to the undead extras’ extraordinary discipline: “The acting experience level of our cast was limited, to say the least, but still everyone was always totally in character. I don’t remember there being abnormal amounts of retakes being done.”

From the get-go, the filmmakers took care to establish fairly strict guidelines to set the parameters for appropriate zombie behavior. Says Russo, “We reasoned that they would move slowly; in fact, they had to move slowly, or else the script would not have worked; it would not have been believable that our hero Ben could elude them after the failed escape attempt.”

The iconic role of the opening cemetery zombie was originally reserved for Russo. “I was going to be the cemetery zombie because nobody else was around to do it. I got into makeup and then Hinzman showed up. We said, ‘Oh good, he can be the zombie because I can still load the magazines and work the clap sticks.’ So there I was all day in zombie makeup working clap sticks and Bill became the famous cemetery ghoul.”

Hinzman worked as a snapper at Latent Image by day and moonlighted as a part-time police forensics photographer. His terrifying performance in Night still sends chills down contemporary spines. “I pretty much picked that up from a film with Boris Karloff,” he reveals. “It was the one where he got electrocuted and he came back to life [The Walking Dead]. He had one arm that was sort of dangling and he was dragging his leg. I think that’s where I got that from, subconsciously.” Marilyn Eastman’s adroit makeup reinforced that resemblance, as did Hinzman’s own hairstyle and coloring. Hinzman later recounted, “I sprayed my hair white and put some black on my cheeks. I was really surprised by how scary it turned out. I’ve been told several times how I scared the hell out of people as the lead ghoul.”

Hinzman had a major fan in Kyra Schon: “Bill Hinzman, the graveyard ghoul (or, as he prefers to be called, ‘#1 Zombie’), was, in my opinion, the scariest looking zombie and my personal favorite. He was my zombie role model. I compare all others to him, and everyone else pales (no pun intended) in comparison.”

That assessment passed a real-life test when Hinzman neglected to get out of character after leaving the set. “I remember coming home one night in makeup, returning to my little four-room hovel apartment, and I walked into the hall where the next-door neighbor was standing. Well, I damned near scared the shit outta her!”

Observant Deadheads have noted that Hinzman’s zombie exhibits a bit more pep than most of his living dead peers. Hinzman explains, “Russell (Streiner) comes to her (Barbara’s) rescue and attacks me. At that point George said, ‘Okay, he’s attacking you, you have to kill Russell.’ I said, ‘How am I supposed to kill this guy when throughout the film you were always telling us that we have no power except in tandem with each other and could only rely on each other for strength.’ And he thought about it for a while and the famous line, in my memory, is, ‘Oh fuck it, just kill him.’” Those were, in fact, the final scenes shot, so Romero might be forgiven for his zombie-empowering impatience.

Many of the volunteers went above and beyond the call of living-dead duty. Romero cites local TV personality Dave James’s drop-dead fall as one of the zombies popped by Sheriff McClelland’s posse as a prime example. “People get up in front of the camera,” he says with wonder, “and all of a sudden someone who’s never done anything like that before does something spectacular like that—that’s a stuntman fall!”

Assembling the zombie-hunting posse proved a relatively easy task. “We were able to drum up lots of cooperation,” says Russo. “David Craig, the actual Safety Director of the City of Pittsburgh, appeared in the film. So did four Pittsburgh policemen with their police dogs.” Adds Hinzman, “The scene with the dogs was a very scary scene for the number one zombie. Because the direction was, ‘Don’t turn around and look.’ And you knew those dogs were right on your butt. And you were hoping they wouldn’t get loose.” Russo also earns props for his participation in that particular sequence: “I was lying down with a 16mm camera right in front of them, with them barking in my face. I thought if they ever break the leash, I’m finished.”

Filling out the posse’s civilian ranks were Evans City citizens who supplied their own firepower. “They were all happy to have guns in their hands,” says Romero. “We had quite an arsenal.” It was George Kosana’s job to keep the posse in line, making sure those guns weren’t loaded. But the extras’ amateur status didn’t earn them any breaks from Romero. Judith O’Dea recalls, “I’ll never forget when George was filming, he had all those men a quarter of a mile, way out into the field, and he yelled, ‘Action!’ These guys, the first take, are intense, walking along there with their guns, and they get a quarter-mile in and George says, ‘Cut! Let’s do it again.’ They must have walked back and forth and back and forth I don’t know how many times—it was hysterical at the end. These guys were practically dragging their rifles, they were so tired.”

While the posse’s all-white, redneck makeup made the film more powerful, especially to midnight moviegoers and African-American audiences, the filmmakers did not go out of their way to achieve that ethnic composition. “We would probably have used anybody and everybody who showed up,” Russo states today, “because we had put out desperate calls for extras, many of whom were friends and friends of friends from Claireton, Pennsylvania, my old home town, where George Kosana and I were living at that time. American society was much more stratified at that time, and so most of the people we closely associated with happened to be white in that small town, although most of us who worked on Night of the Living Dead were not prejudiced in that regard.” Though they would have been accepted, no hippies applied for the gig either. Says Russo, “That fashion wasn’t so big right in the narrow spectrum of time in which Night of the Living Dead was filmed, so it is pure accident that no longhairs showed up.”

Not even the police—or their dogs—were immune to the zombies’ menace. “We were having lunch and it was a posse day,” Bill Hinzman looks back. “I was dressed in a zombie outfit, of course. I was having lunch with one of the girls at a picnic table. One of the cops was sitting there with a German shepherd police dog. And this cop was trying to impress the young lady sitting across the table, saying he was a great dog, he wasn’t scared of anything. One of the girls playing a zombie [Paula Richards] came around the corner; she had on a long white gown and black hair and zombie makeup on. That dog took one look at her and took off in the opposite direction!”

A Night to Remember: What the Living Dead Means to Me

by Allan Arkush

It always struck me as a movie that wasn’t made so much as found moldering in the cellar of an abandoned house. And I do mean that as a compliment. Yes, that’s how convincing I find the movie to be. It looks like it must have really happened!!!

In the early ’80s, when I was directing rock videos, I once met with Motley Crue and presented them with a concept for their next video. I wanted to recreate Night of the Living Dead with them playing the living dead. In the style of the movie, they would be chasing down hot video girls in scratchy 16mm black and white. Sadly, the only part they liked was chasing down hot video girls. Oh, well, a lost opportunity.

A graduate of the unofficial Roger Corman Filmmaking School, ALLAN ARKUSH earned his cult-movie stripes directing the 1979 fave Rock’n’Roll High School, which had its New York City premiere at Night ’s perennial venue, the Waverly Theater. He has since gone on to a prolific career in TV movies ( Elvis Meets Nixon ) and episodic television, executive producing and frequently directing the hit series Heroes.