Читать книгу Night Of The Living Dead: - Joe Kane - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

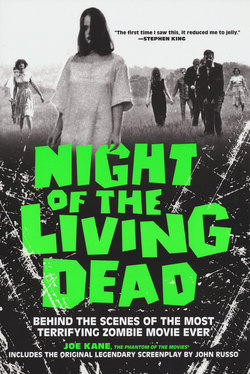

2 DUBIOUS COMFORTS: INTRODUCTION TO THE LIVING DEAD

ОглавлениеThey’re coming to get you, Barbara!

—Johnny (Russell Streiner) in Night of the Living Dead

It was a dark and stormy night, Halloween season, out in rocky Montauk Point, Long Island. We had just left a wedding reception and had driven several blind blocks, through a drenching rain, powered by gale-force winds. Finally finding shelter at the Memory Motel (earlier immortalized by the Stones song of the same name)—and already three sheets to the wind and counting—I wanted nothing more at that exhausted moment than to fall into bed for a solid eight.

First, though, from force of lifetime habit, I instinctively turned on the telly. And what grainy sight should greet my booze-befogged eyes? None other than Johnny and Barbara’s car just starting its doomed journey down that forlorn road to the old Evans City Cemetery, where the eternal, infernal nightmare would begin anew. As lightning and thunder thrashed outside, I obediently settled on the edge of the bed, instantly scared sober by that flickering tube. I dreaded every frame I knew I was about to reexperience, but I was powerless to resist.

That night time-warped me to Times Square, more than a quarter-century before. I had glimpsed Night of the Living Dead adorning Deuce marquees, circa 1969, but, despite that cool title, took it for just another fright flick, one I was always too busy to drop in and see. When Night resurfaced in June 1970, however, at the Museum of Modern Art, where I had a student membership, it seemed a sure sign that this black-and-white indie from the Steel City had been deemed something special. This time I surrendered, eagerly joining an anticipatory audience of art-house lovers and horror hounds in MoMA’s auditorium.

The film opened, natch, the same way it would on the Memory Motel TV, and as it had at several midnight shows I attended at New York City’s Waverly Theater during the ’70s, on VHS in the ’80s, DVD in the late ’90s, and during countless other broadcast airings and streaming video Internet showings: As soon as we sight that lonely vehicle, we sense we’re going on a journey and, given that title and bleak autumnal landscape, we’re pretty sure it won’t be a pretty one. As the car follows the gray brick road to the graveyard, we get the feeling we’re not in Pittsburgh anymore.

Next, we peek inside and pick up on a conversation in progress between impatient big brother Johnny (Russell Streiner) and his prim little sis Barbara (Judith O’Dea). The tedium of their long and, in Johnny’s eyes, pointless drive to pay a perfunctory graveside visit to their deceased dad has reduced the twentysomething siblings to regressive role playing, with Johnny’s teasing Barbara and Barbara chastising Johnny for his immature antics. Sans a single excess frame, the scene perfectly encapsulates both the pair’s longstanding relationship and present situation.

As with all of Night’s major characters, the viewer voluntarily fills in the rest of their backstories based on the few key clues provided. Johnny, we surmise from his suit, tie, and protruding pocket pens, is likely a low-rung white-collar worker. His acceptably longish hair, slightly stylish specs, and driving gloves indicate that the ’60s have encroached on him in a distant ’burb way. But he’s essentially a pretty straight dude, the type who would much prefer watching the Steelers on TV rather than visiting the grave of a father he claims to barely remember. Johnny is relentlessly, even deflatingly pragmatic, but also a bit of a joker.

Barbara, with her conservative coat and proper demeanor, is probably a secretary or similar office support person. We determine that she’s somewhat repressed, almost certainly single, and a virgin. Both siblings, it would appear, still live at home with mom. And, most crucially, neither is played by a recognizable Hollywood thespian; both look like people we see in real life. Already, the film has taken on a distinct documentary feel.

An almost subliminal hint of impending danger is subtly conveyed via a static-interrupted radio broadcast. Johnny, shrugging, switches it off, convinced that what he’s heard is merely a temporary technical glitch. While the siblings place a wreath at the gravesite, Johnny recalls a similar moment from their shared childhood, when his attempts to scare young Barbara aroused their granddad’s rage, provoking their elder to angrily predict, “Boy, you’ll be damned to hell!”

When Johnny senses Barbara’s growing anxiety, he reverts to the same puerile behavior, mischievously invoking Boris Karloff, lisp intact, and uttering Night’s signature line, “They’re coming to get you, Barbara!” If we hadn’t guessed already, we know we’re in deep nightmare territory when Boris himself, or an unreasonable facsimile thereof, suddenly materializes, as if by black magic, behind them.

At first, the film teases the viewer with that distant apparition: Is the figure important? Menacing? Or merely set decoration? We soon learn the answer when he clutches a vulnerable Barbara, stunning us with one of the primo shock moments in horror-film history. Johnny races to sis’s rescue, engaging the mysterious aggressor in a furious fight that seems all the more frightening for its raw, random choreography. This isn’t a Hollywood stunt show; this is an awkward, brutal battle to the death. When Johnny’s head hits a cement cemetery marker with an accompanying thud, the image chills with its abrupt finality. Barbara reacts just as instinctively, running to their car and, despite her terrified state, retaining enough composure to release the emergency brake and roll downhill, even as the single-minded killer shatters the window with a heavy rock.

Alas, Barbara’s escape attempt lasts but a few yards as she plows the car into a tree. There follows a frenzied flight, shown in a blur of multi-angle images further spiked by a panicky soundtrack, as Barbara zigzags down the graveyard road. She never pauses, not even once she’s outdistanced her erratically loping pursuer. In a standard horror film, her nearly three-minute sprint might well tax audience patience. But Night ingeniously ups the terror ante with each frantic footfall, hitting such a hyper pace that the opposite effect takes hold, forcing jangled viewers to share Barbara’s suffocating fear.

When she escapes into an appararently empty farmhouse, Barbara keeps cool enough to lock the door, dial the phone (it’s dead), and snatch a protective knife from a kitchen drawer. A frightened peek outside reveals that two additional fearful figures have joined her brother’s attacker. Shell shocked, Barbara decides to explore upstairs, only to be stopped dead in her tracks by the grotesquely grinning skull of a rotting corpse.

Draped over the banister, Barabara half-slips, half-slides down the stairs. Now she’s freaking out in earnest. She staggers to the front porch, where headlights freeze her, fawnlike, in their blinding glare. Without warning, a face pops up out of nowhere and into frame—a black face. Help or another threat? For the moment, Barbara doesn’t know—and neither do we. When the intruder hustles her back into the house, we realize he’s on her (and our) side. Still, trapped in the imperiled farmhouse with a black stranger while killers mill outside, Barbara’s mental meltdown accelerates.

The man identifies himself as Ben, but there’s no time for personal details or pleasantries. Ben quickly sizes up the situation and takes control, questioning, with little success, the now silent and useless Barbara. He also tries the phone, which emits a weird, faint electronic hum. He, too, discovers the corpse at the top of the stairs and mutters a stunned, “Jesus.” When he stumbles downstairs, Barbara briefly assumes a prayerful position as if responding to Ben’s religious “plea.” But it doesn’t look like any deus ex machina’s on the way to save these souls caught in a sudden living hell.

As Ben moves about the house, we also imbue him with a sketchy backstory never spelled out in the film. We can tell by his speech and comportment that he’s intelligent and highly competent, but his casual clothes suggest that, as a black man in 1968 America, he probably works a job that’s somewhat beneath his abilities. We also suspect, from the otherwise white (and, in the case of the attackers, downright pale) characters we’ve encountered thus far, he’s probably not native to the immediate area but just “passing through.”

While Ben scours the house for food, blood from the ceiling drips on Barbara’s hand. Seeking Ben’s solace, she locates him in the kitchen and absently fondles his tire iron. Her hysterical query—“What’s happening?”—could have gotten a laugh, given the jargon of the time, but it never did at any screening we attended. Ben doesn’t know the answer.

Outside, the zombie ranks continue to swell. The walking dead seem more focused now, hefting stones and systematically smashing Ben’s headlights. He takes his trusty tire iron to one of the creatures, then another, crushing their skulls (at this point, they’re out of frame, though the scene is accompanied by emphatic soundtrack thumps).

One zombie enters the house via the back door and creeps up on Barbara, but Ben swiftly intervenes, wrestling the crippled-looking fiend to the floor. This time the camera doesn’t cut away, and we see the gruesome results of Ben’s handiwork—a large, lethal hole in the zombie’s forehead. Ben dispatches another deader in the doorway. The first zombie’s eyes fly open. Ben commands Barbara, “Don’t look at it!” He drags the body outside and sets it on fire as the other zombies back away.

Stifling his impatience, Ben exhorts Barbara to help him find boards to block the windows and reinforce the doors, vulnerable points of entry the zombies appear determined to penetrate. Barbara is hypnotized instead by a tinkling music box, a genteel reminder of a recent, abruptly smashed past. Ben locates lumber conveniently stashed under the kitchen sink and, working alone, begins boarding up the house. Barbara lends an ineffectual hand in a slow, nearly wordless sequence that again could have bored audiences. By this time, however, most viewers with active pulses are too hooked to fidget; they’re thoroughly fixated on every move, no matter how slight, the screen protagonists make.

While dismantling a table, Ben relates the tale of carnage he’d witnessed at Beekman’s Diner: “I was alone. Fifty or sixty of those things were just standing there.” Once Ben completes his horrific monologue, Barbara begins to tell her story, albeit in the voice of a traumatized child. She trails off, complains of the house’s heat, tugs at her clothes, and again grows hysterical, irrationally insisting they leave and look for Johnny. When Ben opines that Johnny’s dead, Barbara slaps him. In another culturally trailblazing moment, black Ben delivers a solid punch to the white woman’s jaw. He gently places an unconscious Barbara on the couch, then clicks on the radio.

As Ben continues to seal up the house, a newscaster reports an “epidemic of mass murder by a virtual army of unidentified assassins” plaguing the “eastern third of the nation.” Spooky sci-fi theremin music nearly drowns out the announcer’s droning tones.

As people were wont to do concerning the ubiquitous, nerve-numbing news accounts of the latest Vietnam casualty stats, political assassinations, civil unrest, and other routine outrages of the era, Ben only half listens as he dutifully pursues more practical matters. Having discovered the fiends’ fear of fire, he pushes a chair out the door and sets it aflame; the zombies stiffly retreat.

In a hall closet, Ben finds a rifle—and a pair of women’s shoes. He bends down to put the shoes on an awake but frozen Barbara, a gesture that hints of both intimacy and servility; to Ben, the act is purely pragmatic, though we do sense his growing empathy for the terrified girl. The radio reveals that the hordes of unknown slayers are “eating the flesh of the people they kill.” Ben goes upstairs and drags the female corpse down the hallway.

Suddenly, the cellar door swings open. Two men burst forth. Barbara screams. Having assumed the job of Barbara’s protector, Ben rushes downstairs, ready to do battle. He angrily asks the men why they didn’t help them if they knew the two were on the floor above.

The older man, excitable, middle-aged Harry Cooper, responds with equal rancor. Their argument escalates immediately, reflecting the toxic generational discord of the 1960s (where families argued over issues ranging from racism to Vietnam politics to basic life values). Many viewers instantly peg quintessential square Harry, with his bulldozer approach to dissenting opinions, as a petty, bullying know-it-all dad and authority figure. Ben, on the other hand, is a defiant black man, standing in and up for the country’s alienated youth, segregated minorities, disenfranchised poor, and all the oppressed.

Then the Great Basement Debate commences. Should the survivors hole up in the cellar, isolated and blind, as Harry insists, or remain on the first floor, where the enemy’s movements can be monitored and dealt with directly? With Harry representing the Old Right and Ben the New Left, the argument flares with the same intensity that fueled the repetitive political arguments that marked those confrontational times.

The divisive squabble seems to drag on interminably, with each side loudly reiterating its position with no signs of compromise or progress, each more interested in proving its point than coping with a common problem. Tom, meanwhile, plays the role of the undecided youth who listens to both sides and gradually leans toward Ben. That heated discussion is abruptly interrupted by a classic jump scare when, as Ben brushes by, clutching zombie arms suddenly thrust through the boarded window gaps.

Ben and Tom hurriedly beat them back, and then Ben grabs his gun and fires through the window. Bullets, we see, are ineffective against a persistent zombie until Ben drills him through the head. Buoyed by his kill, Ben informs an unhelpful Harry: “You can be the boss down there. I’m boss up here.” Midnight-movie audiences often cheered that moment of underdog defiance.

When her beau summons her from the basement we next meet Tom’s fetching squeeze, Judy. (Like the late Johnny, the two have been lightly touched by slowly spreading ’60s styles, with Tom sporting modest sideburns and Judy bedecked in hip denim jacket and jeans.) As Harry prepares to descend the stairs of ignorance, Tom pleads: “If we work together, man, we can fix it up real good.” But, then as now, that’s not happening with Harry and his kind.

In the basement, we meet the rest of our cast—Harry’s frustrated wife, Helen, and their sick, supine daughter, Karen. When Harry apprises Helen of his unilateral decision to defend their underground Alamo at all costs, Helen spits out, “That’s important, isn’t it? To be right and everybody else to be wrong?” The disenchanted spouses struck many younger viewers as the types who’d likely married for the wrong reasons (sex for Harry, security for Helen) and now, in early middle age, are in too deep to go their separate ways. As soon as Helen hears about the upstairs radio, the basement debate rages anew in what’s becoming one of the most fractious films to surface since Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

Tom calls down that they also found a television. Judy agrees to take Helen’s place in the cellar and look after Karen. Helen thanks her with a heartfelt, “She’s all I have.” (Harry, understandably, doesn’t fit into her equation.) When Harry announces his intention to take Barbara downstairs, Ben grows more fiercely protective: “If you stay up here, you take orders from me—and that includes leaving that girl alone.”

TV reports, meanwhile, elaborate on the earlier radio bulletins about “creatures who feed on the flesh of their victims.” Viewers are strongly advised to burn their unburied dead—immediately: “The bereaved will have to forgo the dubious comforts a funeral service will give.” The locations of emergency rescue stations appear on screen, while speculation about a “Venus space vehicle” spreading radiation adds to the panic. We see a live remote from Washington, D.C., where waffling authorities can’t agree on the significance of those rumors while they’re trailed by a crew of desperate newsmen.

Inside the farmhouse, everyone is in momentary agreement that they should hie to the nearest rescue station. To accomplish that goal, they need to unlock a gas pump to fill Ben’s borrowed truck. The plan calls for scattering the cannibals by tossing Molotov cocktails into their midst. Ben and Tom volunteer to undertake the risky mission.

Before that happens, the film breaks for a rare mellow interlude, a sentimental dialogue between young lovers Tom and Judy. As their exchange unfolds, they calmly prepare the Molotov cocktails, not unlike contemporaneous real-life radicals, a parallel not lost on the movie’s midnight viewers.

Harry throws a few flammable jars from an upstairs window. One zombie catches fire, while the rest scatter. Ben and Tom make their move, with Tom hustling to the truck. Judy impulsively decides to join him, running out of the house amid the predatory dead. Not a good idea.

Ben attempts to hold the creatures off. When he shoots the lock off the pump, his torch is left burning on the ground. Tom clumsily swings the hose, spraying the torch and spreading the fire. Ben tries to tame the burgeoning blaze with a blanket as Tom and Judy scramble for the truck. Too late: The engine ignites. Tom manages to tumble out the door, but Judy’s jacket gets caught on the handle. When Tom dives back in to rescue her, the truck explodes and the lovers are consumed in an instant inferno.

Ben then back-steps his way to the house, wielding his torch for protection. At first, Harry refuses to open the door, then relents and aids Ben in boarding it up. More transgressive moments for the times: Black Ben proceeds to beat the tar out of white Harry, while the flesh-famished zombies—former friends, neighbors and just plain folks—enjoy an alfresco Tom and Judy barbeque, visually conveyed via unprecedented gut-munching close-ups. (While Florida exploiteer and gore movie co-inventor [with partner David F. Friedman] Herschell Gordon Lewis had been splattering the screen with more explicit grue since his 1963 breakthrough Blood Feast, his campy, borderline amateur films furnished none of the impact of Night’s terrifying tableaux.) The feast, meantime, can be—and, in midnight circles, often was—interpreted as a destructive society literally devouring its young.

Back in the house, order is temporarily restored. Ben, Helen, and Harry discuss the possibility of finding the Coopers’s abandoned car, a notion the battered Harry predictably dismisses out of hand. We also learn that little Karen has been bitten by one of the “things.” Further TV reports confirm Ben’s empirical findings that a “ghoul” can be destroyed by a bullet to the head (“Kill the brain and you kill the ghoul”). On screen, roving cops and posse members—who look like the types frequently seen beating up black and youthful protestors on nightly news segments—scour the countryside on a search-and-destroy mission.

Inside the farmhouse, the electricity goes out; the zombies take advantage by launching a fresh offensive. Helen holds the door shut, while Harry again hangs back. When Ben drops his rifle to help Helen, Harry grabs the gun and orders his wife down into the basement. Ben tackles him. A fierce struggle ensues. Ben gains control of the weapon and, drained of patience, shoots Harry in cold blood. Harry staggers down the cellar steps. In his dying act, he tries to touch daughter Karen.

Upstairs, Barbara snaps out of her trance and pushes herself against the door, enabling Helen to break free. Then we shock-cut to one of the reigning money shots in horror-film history: A zombified Karen chowing down on her dead dad’s severed arm. When Helen appears, Karen abruptly drops the hunk of raw father flesh and stalks mom, who falls during her disbelieving backward retreat. Karen retrieves a trowel and gets busy, stabbing mom to death as blood splashes the wall.

Then we shock-cut to one of the reigning money shots in horror-film history: A zombified Karen chowing down on her dead dad’s severed arm.

We’re down again to the original two, Ben and Barbara, trying to halt the zombie assault. Johnny makes his dramatic zombie entrance and reclaims sister Barbara, pulling her out the door into the cannibals’ midst; instinctively, she wraps her arms around her brother, half-resisting, half-succumbing.

Now Ben is the last of the farmhouse Mohicans. As the zombie from the opening-scene cemetery climbs through a window, Ben belatedly follows the late, hated Harry’s advice and barricades himself in the basement, though not before tossing little zombie Karen across the room.

Once downstairs, Ben wearily, warily surveys Harry and Helen’s bodies. Suddenly, Harry’s eyes pop open and Ben seizes the opportunity to kill him again, pumping three bullets into his brain. This time, the act carries no sense of triumph. Moments later, he’s forced to do the same for Helen. Upstairs, the thwarted dead mill aimlessly, sans purpose or direction.

Outside, the scene resembles a post-combat Vietnam morning; as a helicopter buzzes overhead, we can almost smell the napalm. We see an aerial view of Sheriff McClelland’s posse crossing the field on foot, guns at the ready. A newsman intercepts the sheriff for an on-the-spot interview, leading to the following deathless exchange:

NEWSMAN: Chief, if I were surrounded by six or eight of these things, would I stand a chance with them?

SHERIFF: Well, there’s no problem. If you had a gun, shoot ’em in the head, that’s a sure way to kill ’em. If you don’t, get yourself a club or a torch. Beat ’em or burn ’em, they go up pretty easy.

NEWSMAN: Are they slow-moving, Chief?

SHERIFF: Yeah, they’re dead. They’re…all messed up.

Cut briefly to Ben in the basement, then back to the posse and police systematically executing the retreating zombies, whose nocturnal uprising looks to have faded with the morning light as authorities easily quell the rebellion. Ben hears the activity and, with measured hope, climbs the stairs. When he peers out the window, a rifle shot from a posse member terminates his life. All that remains is the mop-up, as Ben is dragged, “another one for the fire,” to a mass funeral pyre in a crushing photo montage as the stark credits appear.

The zeitgeist had been captured in a low-budget film can. In the parlance of the day, Night of the Living Dead had crawled out of nowhere to liberate the horror movie. That is indeed The End for the devastated viewer. But how did this dark cinematic miracle begin?

SHERIFF: Well, there’s no problem. If you had a gun, shoot ’em in the head, that’s a sure way to kill ’em. If you don’t, get yourself a club or a torch. Beat ’em or burn ’em, they go up pretty easy.