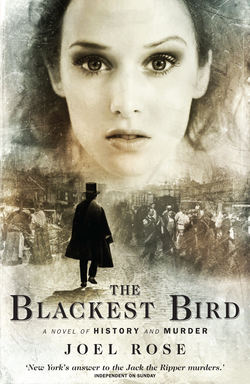

Читать книгу The Blackest Bird - Joel Rose - Страница 25

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление11

Aftermath to Murder

The idea for the Colt revolving handgun came to John Colt’s brother, Samuel Colt, while the latter sailed on board a transoceanic liner to England. Traveling in the company of middle-born brother James, second of the three Colt brothers, Sam, the eldest, had positioned himself on the bridge, where he became entranced with the spinning of the ship’s spoked wheel. He spent the rest of the voyage carving a wooden prototype of a gun barrel capable of a similar spinning action. Upon docking at Leeds, the brothers booked immediate return passage, steaming directly back across the Atlantic to New York and their fortune.

According to John’s written confession, later published in its entirety in a supplement edition of Bennett’s Herald, on the night of the Samuel Adams murder, his brother was booked at the City Hotel on Chatham Street near the southern edge of City Hall Park, but when he stole out of his Chambers Street office and hurried south across the park to see him, Sam was engaged in negotiations in the hotel’s reading room with two gentlemen, one a Brit, the other a Russian, and only a few words passed between the brothers.

“I sat patiently,” John wrote, “trying to wedge a word in edgewise in an attempt to communicate my dire peril to my sibling, but to no avail. Serious money was being discussed and the terms were complicated. My brother has never gotten along well with the British, and the Russians are a total enigma to him,” John explained.

“Exasperated by my brother’s indifference, I finally stood, made a noise in my throat, and exited the hotel, scarcely noticed. I then retired to nearby City Hall Park, where I walked a bit. A turn I enjoyed wholehearted, serving to clear my head, heart, and lungs. My thoughts, I confess, kept coming back to the horrors of the excitement that had only recently transpired, the possible trial, the public censure, the false and foul reports that would inevitably be raised.

“I knew full well there would be those who would wish to take advantage of the nature of my situation, making the deed appear worse than it really was for the sake of a paltry pittance.

“I knew I must somehow disengage myself from all circumstance. After wandering in the park for more than an hour, I settled on a course of action and returned to my room.

“A crate stood in the offices, and I succeeded in stuffing Adams inside, being careful to wrap the body in canvas in order to absorb the excessive amounts of blood which was still leaking. The head, knees, and feet were still a little out, but by reaching down to the bottom of the box and pulling the body a little towards me, I readily managed to push the head and feet inside. The knees still projected somewhat, and I had to stand on them to get them down.

“With this task accomplished, I then fit the cover to the box and nailed it shut using the same hammer/hatchet tool with which I had dealt Adams the death blow. A poetic conceit, I concede, not lost on me.

“I then removed all clothing from the corpse to prevent identification, because my plans now included shipping the body south to New Orleans in a steamer. I therefore took the bloodied clothes, shredded them, and took them to the backyard privy, where I threw them in, together with Mr. Adams’ keys, wallet, money, pencil case, and all other incidentals.

“Thereupon I returned to my room, cleaned up the last of the blood, took the water pail, carried it downstairs, and threw its murky contents in the street, following with several pails of fresh water from the pump opposite the outer door of the building in order to wash away the reddish brown stains.

“After rinsing the pail, I then carried it back upstairs, returning it clean and two-thirds full of water to the room, opened the shutters as usual, drew a chair to the door, and leaned the back against the inside of the door underneath the knob as I closed it. I then locked the door with the key and went at once to the Washington Bath House on Pearl Street near Broadway.

“On my way, quite by coincidence, I met, of all people, Edgar Poe, in the city from Philadelphia on what he said was business.

“The man is an acquaintance,” Colt wrote, “but somewhat more than that. He was peering into a tea shop window on Ann Street. I invited him to accompany me to the bathhouse as my guest.

“As we walked, I did my utmost to maintain my calm and hide my trepidation in light of what had only recently transpired, but eventually I did mention to my friend the claim of Adams that rumor was on the wind that he, Poe, had written the poems signed with my name, and the work, not to mention both of us, would soon be under public scrutiny.

“To his credit, Mr. Poe dismissed such notion as ridiculous. He instead offered me his best wishes for good luck for the book’s appearance. He mentioned to me a new poem of his own, at this point a mere sketch, but for which he seemed to have great hope.”

COLT WENT ON in his Herald confessional to claim Poe purportedly admitted the idea for the verse came directly from a line in Dickens’ Barnaby Rudge, one extolling an owl, Colt thought, which Poe had conjectured to him he might very well transform into a black bird, perhaps a crow, or raven.

Colt admitted he could not quite remember, and had not read Dickens’ book.

Once at the baths, Colt wrote, the two men fell back and spent the rest of the evening discussing the murder of Mary Rogers. Colt alleged they both knew this young woman from Anderson’s and shared remorse for her fate. According to Colt, Poe confessed to him that news of Mary’s death had distressed him greatly, more so than he might have thought.

At this point, Poe turned to him, confiding in a craving for opium. He asked if Colt knew of any person from whom such potion might be procured. Colt, invested in being immensely well-regarded among his fellows for his late night gallivants through the city’s darkest corners, what was known as “elephant hunting,” readily mentioned a retreat he knew, a place known as the Green Turtle’s, beneath the arch on Prince Street, warning Poe that the proprietress, a woman of enormous girth, was exceedingly dangerous.

Afterwards, the men bid good night and Colt went home. He reported he lived with his mistress, as he described her: his lady love, Miss Caroline Henshaw.

Upon his entrance into the bedchamber, Miss Henshaw awoke to ask where had he been. He said he told her he had been with a writer friend from Philadelphia, although he did not mention Poe’s name specifically.

Colt confessed he dared not tell Miss Henshaw what had transpired earlier in the day, and pretended instead to be inspired from his meeting with the unnamed poet. He retired to his desk to write, although he said he was not able to compose a word. Eventually she became quiet and slept, her breath regulating, and only then did he follow suit, slipping into bed and, after a long period staring sight-lessly into the dark, eventually falling asleep as well.

The next morning, having thought better of his predicament, he hired a burly man to carry the crate containing the body of Adams downstairs from the printing office. Refusing Colt’s assistance, the rough, powerful man hefted the makeshift coffin onto his back, muscling it down the stairs and into the street. Colt said he then paid the brute some twelve cents for his efforts and went off to Broadway, where he located a cartman, who would in fact be his undoing. When reward was offered for any knowledge of the whereabouts of Adams, this was the lout who came forward to tell the authorities how he had taken a suspicious oblong box from Colt’s granite building to a packet bound for New Orleans lying in the East River at the foot of Maiden Lane.

The boat had yet to sail, so the wooden crate was dug out from the hold, and sure enough, opening it, the captain and his mate found the printer, stinking, dead, stiff with rigor mortis, and in the most uncomfortable-appearing position.