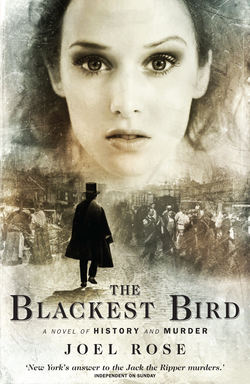

Читать книгу The Blackest Bird - Joel Rose - Страница 34

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление19

The Sister of the Pretty Hot Corn Girl

When Tommy Coleman married the Sister of the Pretty Hot Corn Girl, over a thousand members of the Five Points gangs attended the wedding, and there was much shouting and loud singing among these roughs, toughs, and bruisers of her anthem in chorus with the laughing, drunken Irish hordes tramping through the streets.

TOMMY COLEMAN had run into his future wife, the sister of his dead brother’s murdered wife, one night after not seeing her since his brother’s hanging. She came in off the street into Murderers’ Mansion, One-Lung Charlie Mudd’s bucket of blood on Little Water Street.

The last time Tommy had seen her she was being escorted through the Tombs’ front gate by sheriff ’s deputies to stand near the gibbet, close enough to touch the naked wood. She had come to Tommy’s brother’s hanging for one reason, and one reason only: she wanted to see the man who had murdered her sister pay the big price and swing for what he had done.

That night everybody in the Mansion knew her, knew who she was, what had happened, her and her family’s torment. The girls from the neighborhood admired her for her strength and wherewithal, and bravery, the way she wore her air of tragedy, and she was so pretty, just like her sister, they longed to be like her; and the men, in awe of her beauty, felt the stirrings of wanton lust if nothing else.

She was known by sight on the street and whispered about. Not only because she was the sister of the city’s most famous hot corn girl, but also because she stood squarely on her own two feet, and had aligned herself with none other than Ruby Pearl, the rough-and-tumble leader of the Bowery Butcher Boys, and she, it was gossiped, if not said out loud (certainly not to her face), was in way over her head.

Not only because she was Irish Catholic and Ruby Pearl Protestant, him a prideful, east-of-Bowery, native true-blue American, her a potato-eating Irish lass from “the P’ernts,” but also because she was only sixteen and he a hardened eleven years her senior, and Protestants didn’t come a-social-calling in that neighborhood from where she was from, especially right there in the heart of the Fourth Ward, and old Ruby Pearl, he could be a very bad fellow, if not the worst. Very rowdy he was, and tough on women of all ages, save maybe his own mother.

When she sashayed into Charlie Mudd’s and Tommy glanced up, he had been cavorting there with his boyos, Tweeter Toohey, Pugsy O’Pugh, Boffo the Skinned Knuckle, and the rest of their lot. Her face flushed, full of rage, her dressed in gingham, her hot corn bucket slung over her shoulder like a weapon, her breath coming fast, he saw her, her excitement and anger transmitted to every patron imbibing in the Mansion, everyone laughing and singing and carrying on, and Tommy knew right there and then in his heart of hearts, this bleak mort was destined to be his bleak mort, none other.

Tommy Coleman did not deceive himself. He had no self-delusions what he was getting into. He had heard the talk. He knew to whom she belonged, and what her feelings had to be toward him personal, given her deceased sister and his executed brother. There had never been love lost between them, even when things were going good with their respective siblings. He didn’t give a flying fig. He knew what he wanted, what he had to have. He knew no matter what had preceded, anything was possible in America.

So he sat there, biding his time at the knife-scarred table, having patience, waiting for something fateful to happen, biting his lip to blood as she stormed around Charlie Mudd’s emporium so angered and full of herself, beautiful and barefoot, the strap of her cedar bucket crossing her bosom.

There was a commotion and into the Mansion stalked Ruby Pearl himself, surveying the drunks for her. What she’d been waiting for, judging from the look on her face. She marched across the room, stood in front of him, rage sparking off her, and you better believe every citizen in One-Lung Mudd’s Mansion knew old Ruby, big as he was, strong as an ox, tough as a sheep shank, was in trouble.

Ruby Pearl was not known for an abundance of brains so he might not have known he was in dire straits yet, leastways that was the only way Tommy could ken it. Which, you have to figure, is why Butcher Pearl said so casually to her in front of all these citizens, “Why you make me follow you in here, you damn mort? Why you coming in here? Why you ain’t out working still?”

“Am I in?” she shot back without fear. She had that God-given ability, young as she was, that enables a woman to put an edge in her voice that sets a man off.

Ought to have made Ruby Pearl be more aware, but not knowing the whims and subtleties of the female gender, having worked the whole of his life in slaughterhouses and market butcher stalls, Ruby Pearl only heard what he thought—affront and disrespect—and he hauled off to strike her.

Tommy was on his feet, crossing the sawdusted floor fast, coming to her defense.

Except the Sister of the Pretty Hot Corn Girl didn’t need (or want) any strong-arm protection offered up by the likes of Tommy Coleman.

She despised Tommy Coleman.

She caught Ruby Pearl’s big arm in midair, before he could strike her, and she just sneered up at him like he was nothing, lower than a worm, a mesomorph, holding him fiercely, digging her fingers into the flesh and muscle and tendon in the seam of his thick wrist, the electric ganglionic nerve, smelling on him the overpowering smell of dead animals, her crazy smile, if you can call it that, a smile, God, could you believe it? In his cell Tommy grinned to himself as he remembered how beautiful she was!

Tommy was left to standing and staring. There was nothing for him to do, just look on and grin, Ruby Pearl dispatched just like that. Everything taken care of by this beautiful girl, neat as a pin.

Nevertheless, Tommy felt like he needed to make his presence known, and then he was of a mind to have a word with old Ruby. After all, he, Tommy, had got up and crossed the room this far, might as well go all the way.

Butcher Boy Ruby Pearl, wobbled from beer and oysters, toughest of the tough, roughest of the rough, whirled, rubbing his wrist where his bleak mort had pinched him, or whatever she’d done, and turned on Tommy, now focused in on this nemesis, glaring at him as a man glares at another when it is understood between them that their manhood is at stake.

Ruby Pearl knew Tommy Coleman, knew him all too well, knew how crazed and dangerous he was; loathed him. Loathed Tommy as Tommy loathed him.

“Pearl,” Tommy spoke.

“Step back, Coleman,” Ruby countered, “before I punch your parking railing through your face.”

“Don’t you know that’s no way to treat a lady, boyo?”

“I ain’t no b’hoyo of yours. Don’t call me no b’hoyo, b’hoyo! I’m Ruby Pearl, Bowery Butcher B’hoy. Mr. Pearl to the likes of you, Coleman.” And advancing on the Sister of the Pretty Hot Corn Girl, he growled mightily, “Go back to the street, you. Make money, and leave me to deal with the likes of this nickey. I don’t want you to see what I’m gonna do to him.”

“Mr. Ruby Pearl, you don’t belong down here in this part of the city,” Tommy Coleman said. “This ain’t your neighborhood, this ain’t your ward. I think you better go home, back to your Bowery ways. Before you can’t, boyo.”

“Meaning what?” Ruby Pearl was not a man to step down lightly. “I’m here to see my mort. On her invitation. This is a free nation if you know it or not, you little Irish runty pig.”

Ruby was over six feet two inches tall and weighed more than two hundred and twenty pounds, with the torso of a side of beef. He grew up on the street. But sometimes the biggest and the strongest, the slyest and the most adept, cannot win. Looking around him, Ruby knew when he was put down and could not persevere. Even against a straw-weight lad a foot inferior, a hundred pounds lighter than he.

Tommy’s gang, Tweeter, Pugsy, Boffo, a dozen others, their hands on their slungshots and daggers, surrounded him.

“You’ll get yours, Coleman,” Ruby growled, looking from one to the other. “I’ll be back one day to dispatch you to hell, or I’ll meet you on the streets and grind you into the paving stones then. You know that, don’t you, wee one, when you don’t got your life preservers around.”

“I’m not scared, mate,” Tommy told him.

“Neither am I,” retorted he.

All in attendance at Mudd’s Mansion that night, every single one, pressed forward one step to witness what was to transpire.

“One last thing, Mr. Pearl. From now on, stay away,” Tommy warned, spitting on the floor between Ruby’s feet for punctuation. “This here mort is not your mort no more.”

“Oh! Oh! Oh!” Pearl said. “Now you’re telling me stay away from what’s mine.”

“I don’t like no man who hits no woman.”

“No? Well, it ain’t no secret I don’t like you, Tommy b’hoyo. And I don’t much like no Irish pig runt rat telling me what to do.”

“Stay away, Ruby. Stay away if you don’t want to be took out.”

RUBY PEARL SWORE up and down the Bowery that vengeance would be his. He enlisted the other local native gangs to join his throng of Butcher Boys: the True-Blue Americans, the American Guard, every last stick and straw of the rest of the Bowery russers, making threat to march on Tommy Coleman’s wedding, the festivities of which were to be held in Paradise Square, and fillet Tommy on the spot in front of his new bride, making her a widow.

Armed guards, all emanating out of Eire, and all over six feet tall, were volunteered, primarily out of the ranks of the Plug Uglies and Kerryonians, to protect the nuptial celebration. These giants, in their reinforced stovepipe hats and hobnailed boots, were located strategically on the Five Points side streets and alleys and around the wrought iron fence that surrounded the square, as added deterrent, per Tommy’s orders, a rusted but workable cannon placed on Cross Street facing east.

But all was quiet and the wedding went off without incident.

Still, a small, festively wrapped box came, delivered by a toothless old woman in a yellow head rag. In it was the carcass of a dead white piglet, and a note that read: IT’S NOT OVER YET, with no signature, no nothing, but Tommy Coleman needed no signature to know the low style of a Bowery Butcher Boy.