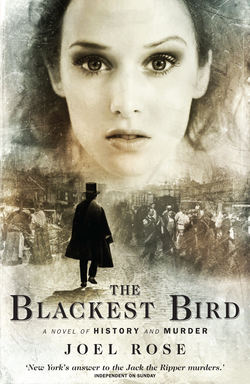

Читать книгу The Blackest Bird - Joel Rose - Страница 33

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление18

The Tombs

The Tombs is an unholy place. One drafty corridor links to another drafty corridor. One drafty cell abuts another drafty cell. The stink and unhealth of the swamp rises from beneath the foundation. The mortar is mildewed from moisture, foul from mold.

In the spring of 1842, the author Charles Dickens, on tour of the United States for a book he was writing, American Notes for General Circulation, requested specifically to visit the prison.

As High Constable Jacob Hays watched from his desk, the great man, the most popular writer in America despite him being an Englishman, was escorted through the Tombs’ corridors, at one point inquiring of his guide, a jailer named Trencher, “Pray, my good man, from where does the name Tombs derive?”

“Well, it’s the cant name,” came the reply from the blue-suited keeper, meaning the argot used by beggars and thieves.

“I know it is,” Hays heard the novelist snap, obviously impatient with those he perceived as simpletons. “But why?”

“S-some suicides happened here, when it was first built,” the beleaguered guard ventured. “I-I expect it come about from that.”

Hays rose from his desk then and came over to where the author stood.

“Forgive me, sir, for the interruption, but this is not from where the sobriquet comes. If you will, the House of Detention became known as the Tombs because a number of years ago the whole of this city was taken over with an Egyptology phenomenon.”

With Trencher looking on gratefully, Hays introduced himself and went on with his account.

A writer from Hoboken, he explained, H. L. Stevens, had set out for Arabia, returning with a manuscript entitled Stevens’ Travels, which became a sensation for the publishing house owned by Mr. George Palmer Putnam. The author made drawings to accompany his text, and one of these depicted an ancient mausoleum deep in the desert. The idea of this romantic crypt whetted the public’s collective imagination, the city fathers deciding in a moment of inspiration that the newly planned prison must be a replica of this Saharan vault.

THE FIRST MAN ever executed in the Tombs had been none other than Tommy Coleman’s brother, Edward Coleman. Hays saw him hanged in the prison courtyard on the morning of January 12, 1839, shortly after the building’s completion; his offense, the murder of his wife, a hot corn girl.

Hot corn girls walked the streets, selling their wares out of cedar-wood buckets hanging by a strap from around their necks. Barefoot, known for their striking beauty, dressed in calico dresses and plaid shawls, these young ladies and girls came out of the poorest neighborhoods, especially the Five Points, their song familiar in one version or another to every city dweller:

Corn! Hot corn!

Get your nice sweet hot corn!

Here’s your lily white hot sweet corn!

Your lily white hot corn!

Your nice hot sweet corn!

Smoking hot!

Smoking hot!

Smoking hot jist from the pot …

Sports, picturing themselves blades, trailed the hot corn girls on their routes, vying for their attention, entranced by their cry. Competition among the girls was intense—as it was among their admirers. More than one pitched battle erupted over the favors of a hot corn girl, more than one deadly duel.

Edward Coleman pursued, and eventually conquered, a girl so fetching, so beautiful, that she had come to be known above all others as “the Pretty Hot Corn Girl.”

Years earlier the city gnostics had undertaken to fill in the old freshwater Collect. Employing poor labor and public works, the brilliant ideapots ventured to have the surrounding hills shoveled down west of the pond near Broadway. After draining off the water, they planned to use the earth and bedrock from this excavation as a base foundation.

In addition a large open sewer was dug. Originating at Pearl Street, it ran through Centre Street to Canal and then followed an original streambed to the Hudson River on the west side. It was hoped this sewer would effectively keep dry the newly drained surrounding property, and thus appreciably add to the stock of usable acreage.

Local politicians congratulated themselves and anointed the project a success as multitudes of the rich clamored to build houses on the landfill, and for a time, everything was quite lovely. Hays had one single roundsman seeing to the security of the entire neighborhood, and at the southern end Paradise Square, on a balmy summer evening, was just that—paradise.

But then disaster struck. The underground springs that had once fed the Collect proved to be improperly capped, and the landfill had been mixed in large part with common garbage. The lovely new homes began to sink into the soft ground, springing doors and windows, and cracking façades. Water seeped into foundations and filled basements. Noxious vapors and fetid odors began to rise from below, cholera and yellow fever seeping upward.

All at once the rich moved out and the poor moved in, mostly penniless Irish immigrants of the lowest class and freed Negroes. The neighborhood came to be known as the Five Points, renowned as the worst slum in the world, according to what Dickens was saying, surpassing even London’s fabled Seven Dials for its misery.

Tommy Coleman’s brother, Edward Coleman, pictured himself a fierce, rough cove. His was the Forty Thieves, one of the first truly large criminal gangs to roam and terrorize New York’s streets. Under his clever leadership, the gang established themselves in and around Rosanna Peers’ greengrocery on Anthony Street, behind the Tombs, in the heart of the Five Points slum.

Outside Mrs. Peers’ grocery, on racks and in bins, were displayed piles of decaying vegetables. These were touched by no one, especially the tomatoes, which were regarded as poison.

Inside, in the back room, congregated Coleman’s ruffians: thugs, thieves, holdup artists, soaplocks, pickpockets, political sluggers, and no-gooders; one and all, at an instant, armed and ready to follow their leader’s command, to rise and roam, primed to terrorize the local streets, especially after indulging in the fiery liquor served up by Mrs. Peers at a price unequaled by the nearby, more established drinking emporiums, saloons, groggeries, and assorted buckets of blood.

To give him his due, vicious and intense, Edward Coleman’s acknowledged talent was indeed to lead and organize this hoary crew of cutthroats. In a city chockablock with rapscallions and street toughs, his was the first gang with designated leadership and disciplined members. In a weak moment, Old Hays might even have admitted to guarded admiration for the man’s skills. After all, under Coleman’s tutelage, his gang’s membership in general substantiated over time a more honorable lot than the average jaded politico or two-shilling heeler walking the city’s ward streets.

But as pretty as the Pretty Hot Corn Girl was, marriage to a man the likes of Tommy’s brother proved to be too great a hurdle for her to overcome. Three weeks after the ceremony at Our Lady of Contrition, in a fit of alcohol-fueled rage, Edward Coleman murdered his wife, and for this senseless act was sentenced to pay the big price.

Eager not only to witness the dramatic end of the Forty Thieves gangleader, but also to view the new Tombs penal facility for the first time, so many city dignitaries and men-about-town came out to attend the event, it took the condemned man more than twenty minutes to shake all the hands extended him by well-wishers.

Finally, he took his place beneath the gibbet and the hemp necklace was looped around his neck, the counterweight poised in position.

Outside the prison walls hordes of his base underlings, including his adoring fourteen-year-old brother Tommy, not admitted due to warden’s orders for fear of disruption or worse (jailbreak), cheered and shouted his name.

At a signal the weight dropped, the scientific intent being that the condemned would be jerked by the neck into the air, what had come to be known as “the jerk to Jesus,” there to dangle unto death.

But on this morning, in front of Old Hays’ eyes, the rope snapped with a frightening twang.

Loud voices rose from the crowd, “Will of God! Will of God!” as Edward Coleman, smiling broadly, stood stock-still, unfazed. The frayed rope still looped about his neck, he winked at Hays.

Vocal supporters gruffly began to shout, “The Almighty has intervened!” demanding that he be spared.

Refusing to hear anything of it, Monmouth Hart, warden of the Tombs and one of the most ardent admirers and customers of the murdered Pretty Hot Corn Girl, interceded, and with Hays standing at the gibbet edge watching, calmly instructed the hangman to restring the murderer and try again.

This time all went as planned to hip-hip-hoorays and loud hoorahs from the solid citizenry in attendance, Edward Coleman’s body swinging from the crossbeam in front of Old Hays for a full fifteen minutes before Coroner Archer came forth and gave the sign for it to be cut down.