Читать книгу Food of Jamaica - John DeMers - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

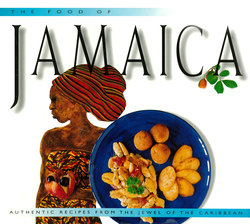

ОглавлениеA typical island breakfast of Run Down (recipe page 62), boiled green bananas and potatoes.

Part One: Food in Jamaica

Beneath misty mountain peaks lies a land of infinite complexity

Jamaica is a lush tropical place offering intense adventure amid one of the most tangled cultures on the face of the earth. It vibrates with the rhythms of reggae, is enlivened by the spices of pepperpot and jerk and shimmers with the bright colors of flowers and paint.

To think of Jamaica is to picture an island paradise of steep; cloud-bedecked mountains and jewel-like blue lagoons—a land of holidays and relaxation. But there is much more to this island.

Jamaica stands out among the islands of the Caribbean for several reasons, first for its sheer size: it is the third largest island in the Caribbean. With more than 4,000 square miles, Jamaica is one of the few Caribbean islands with agriculture, thus adding depth and variety to its cuisine while liberating its people from subsisting on imported foodstuffs.

The second reason for its uniqueness is the complex ethnic makeup of its people, who were brought or came to Jamaica because of its vast tracts of tillable soil.

Today’s Jamaicans are the descendants of the Amerindians, the European colonists, the African slaves, and those who came later—Germans, Irish, Indians, Chinese, Lebanese, Syrians and Arabs.

Jamaica’s cuisine is the product of this diverse cultural heritage, and its food tells the story of its people. The cuisine’s unique flavors include mixtures of tanginess and burning hot pepper, the rich complexity of slowly stewed brown sauces, the spice of intense curries and the cool sweetness of its many tropical fruits.

Some of the most authentic examples of the island’s food are found in the most humble roadside eateries. And some of its best new fusions can be discovered in the island’s hotels and restaurants, being prepared by chefs who are joining traditional flavors with new ingredients.

This book aims to unravel Jamaica’s many-faceted culture and make it come alive for you. Whether you have visited often or never, these pages will cast light onto the island’s history, culture and, most of all, its cuisine. The recipes offered here run the gamut of the island’s offerings—from the most humble, but tasty, fried bread to its spiciest jerk chicken.

Perhaps by reading in these pages about Jamaica’s history, landscape, people and food, you will begin to share the pleasures of this multilayered island paradise, which is as complicated as its stormy history and many cultures, as beautiful as its rare wildlife and flowers and as unforgettable as its easy yet knowing Caribbean smile.

Native Soil

An Eden-like land of fertile fields and sandy beaches

From its primal beginnings, Jamaica was ripe for harvest. “The fairest land ever eyes beheld,” scribbled an eager new arrival in his journal. “The mountains touch the sky.” This visitor was hardly the last to be awestruck by Jamaica’s beauty, but he was probably the first to write anything down. The year was 1494. The visitor was Christopher Columbus on his second voyage to the New World, and he had come to claim this “fairest land” for God, for himself, and for Spain.

Hardly a set of eyes has settled on these mountains, waterfalls and hills that roll and dive down to the palm-fringed sand, without the beholder thinking he was seeing the biblical Garden of Eden. It is important, however, to understand the interworkings of nature and man that have shaped Jamaica.

Known to Jamaica’s first residents, the Arawaks, as Xaymaca (land of wood and water), the island was just that before the arrival of Europeans. It featured the two elements in its name—both important to the Arawaks and anyone else hoping to settle here—but little else except a tangle of mangroves. For all the human suffering they brought, the Spanish and British also covered the island with colorful, edible vegetation. The tropical fruits and flowers of this beautiful island are transplants from places like India, China, and Malaysia. Still, nature has been bounteous, offering its many colonists fertile fields in addition to beauty and other resources. The colonizers visited many other Caribbean islands, leaving most of them as spits of sand dotted with a few palm fronds. But in Jamaica they stayed, shaping the island to their own image.

Collecting and counting bunches of bananas to fill the cargo holds of boats destined for North America. On the return trip the boats were filled with a very different sort of cargo—tourists escaping the bleak northern winter.

Located in the western Caribbean, Jamaica is larger than all but Cuba and Hispaniola. Millions of years ago the island was volcanic. The mountains that soar to nearly 7,500 feet are higher than any in the eastern half of North America. These peaks run all through the center of Jamaica. The island has a narrow coastal plain, no fewer than 160 rivers and a dramatic coastline of sand coves. Much of Jamaica is limestone, which explains the profusion of underground caves and offshore reefs—not to mention the safe and naturally filtered drinking water that first impressed the Arawaks. In the mountains of the east (the highest, Blue Mountain Peak, rises to 7,402 feet) misty pine forests and Northern Hemisphere flowers abound. Homes there actually have fireplaces, and sweaters are slipped on in the evenings. In places, the mountains plunge down to the coast creating dramatic cliffs.

The hotter, flatter southern coast can look like an African savanna or an Indian plain, with alternating black and white beaches and rich mineral springs. There are tropical rain forests next to peacefully rolling and brilliantly green countryside that, save for the occasional coconut palm, could be the south of England. It is surely one of history’s quirks: many parts of Jamaica (a small place by the world’s standards) resemble the larger countries from which so much of its population hails.

In the heyday of the British Empire, flowering and fruit trees were brought from Asia, the Pacific and Africa; evergreens came from Canada to turn the cool slopes green; and roses and nasturtiums came from England. The ackee, which is so popular for breakfast, came from West Africa on the slave ships. Breadfruit was first brought from Tahiti by no less a figure than Captain Bligh of the Bounty. Sugar cane, bananas and citrus fruits were introduced by the Europeans.

A late nineteenth-century print of Muirton House and Plantation, Morant Bay.

Jamaica did send out a few treasures. One of the island’s rare native fruits, the pineapple, was sent to a faraway cluster of islands known as Hawaii. Its mahogany was transplanted to Central America. There are varieties of orchids, bromeliads and ferns that are native only to Jamaica, not to mention the imported fruits like the Bombay mango that seem to flourish nowhere else in this hemisphere.

The island is clearly a paradise if you are a bird, simply based on the number of exotics that call it home. Native and migratory, these range from the tiny bee hummingbird to its long-tailed cousin the “doctor bird” to the mysterious solitaire with its mournful cry. Visitors to Jamaica’s north coast become acquainted with the shiny black Antillean grackle known as kling-kling, as it gracefully shares their breakfast toast. And those hiking through the high mountains can catch a glimpse of papillo homerus, one of the world’s largest butterflies. Unlike most of the population, animal or human, papillo homerus is a native.

You don’t have to rough it to see gorgeous views in the Blue Mountains. Spectacular scenery can he viewed from the roads that wind across the region.

A tropical climate prevails in Jamaica’s coastal lowlands, with an annual mean temperature of about 80 degrees Fahrenheit (26.7 degrees Celsius). Yet the heat and humidity are moderated by northeastern trade winds that hold the average to about 72 degrees Fahrenheit (22.2 degrees Celsius) at elevations of 2950 feet (900 meters). Rain amounts vary widely around the island, from a mere 32 inches annually in the vicinity of Kingston to more than 200 inches in the mountains in the northeast. The rainiest months are May, June, October and November with hurricane season hitting the island in the late summer and early autumn.

The Jamaican economy relies heavily on agriculture, though the island is blessed with mineral deposits of bauxite, gypsum, lead and salt—the bauxite constituting one of the largest deposits in the world. Despite its significant diversification into mining, manufacturing and tourism, the island continues to struggle against a budget deficit each year. Agriculture still employs more than 20 percent of the Jamaican population. While sugarcane is clearly the leading crop, other principal agricultural products include bananas, citrus fruits, tobacco, cacao, coffee, coconuts, corn, hay, peppers, ginger, mangoes, potatoes and arrowroot. The livestock population takes in some 300,000 cattle, 440,000 goats, and 250,000 pigs.

This is the lush backdrop to life on this Caribbean island. Of course, no profile of Jamaica would be complete without a description of its single most unforgettable resource: its people.

Out of Many, One Nation

Commerce and colonialization shape the face of a new nation

Listen closely in Jamaica and you will hear a thousand references from well beyond this Caribbean island. Jamaicans speak of places in England and in Israel—from Somerset to Siloah, High-gate to Horeb—except that these places are in Jamaica, too. And hopping aboard a bus, you will encounter Arawak place names like Liguanea, Spanish names like Oracabessa, and entirely Jamaican flips like Rest-and-Be-Thankful, Red Gal Ring and even Me-No-Sen You-No-Come.

These place names reveal the country’s many influences, and, indeed, Jamaica’s 2.3 million people form a spectrum of races that would give the most dedicated genealogist a migraine. Most people are black, or some shade of brown, but many have undertones of Chinese, East Indian, Middle Eastern (known on the island as Syrian, no matter their origin) and European. Five centuries after Columbus, the rainbow of natural colors in Jamaica’s landscape is still vibrant. And there is no better metaphor than this rainbow for the mix of Jamaica’s cultures. With its tension and its tolerance, this island is truly one of the globe’s most fascinating ethnic environments.

Devon House, an 1881 mansion, was built by George Stiebel, a black Jamaican who made his fortune in South America. It once housed the National Gallery and is open to the public.

The first of many peoples known to hit the beaches of Jamaica did so about a thousand years after the death of Christ. Amerindians paddled their canoes over from the Orinoco region of South America. Before that, there is the possibility that a more primitive group, the Ciboneys, spent some time here on their trek from Florida to other large Caribbean islands. The Arawaks, however, left their imprint on Jamaica.

When Christopher-Columbus stepped ashore in 1494, the island had already served as the Arawaks’ home for nearly five hundred years. They were, by all accounts, gentle folk. Their way of life included hunting, fishing, farming and dancing their way through a calendar of festivals. The Spanish, however, had other plans, forcing them into hard labor and killing the last of them within fifty years. Once they had Jamaica to themselves, the Spanish seemed to decide they didn’t really want it. Their searches of the interior turned up no quick-profit precious metals, so they let the land fester in poverty for 161 years. When five thousand British soldiers and sailors appeared in Kingston harbor in 1655, the Spanish simply fled.

This Rastafarian, selling Caribbean lobster near Buff Bay, grows a beard and dreadlocks to demonstrate his pact with Jah (God). The Rastafarian religious movement grew out of Jamaica’s slave society.

The next three centuries under English rule provided Jamaica with its genteel underpinnings and the rousing pirate tradition that enlivens this period of Caribbean history. British buccaneer Henry Morgan was close friends with Jamaica’s governor and enjoyed the protection of His Majesty’s government no matter what he chose to plunder.

The notorious Port Royal (known as the Wickedest City in Christendom) grew up on a spit of land across from present-day Kingston. Morgan and his brigands found a haven there where ships could be repaired and loot could be spent. Morgan enjoyed a prosperous life. He was actually knighted and appointed lieutenant governor of Jamaica before the age of thirty. Port Royal, however, did not fare so well. On June 7, 1692, an earthquake tipped most of the city into the sea, and a tidal wave wiped out whatever was left. Port Royal disappeared. Recently, divers have turned up some of the treasure, but most of it still waits in the murky depths.

The eighteenth century was prosperous for Jamaica’s sugar barons, who ruled as undisputed masters of their British plantations. The island became the largest sugar-producing colony on earth, mostly through the sweat of African slaves. Magnificent residences known as “great houses” rose above the cane fields. Fortunes built on sugar were the envy of even England’s king, giving rise to the expression “rich as a West Indian planter.”

Such words, of course, had little meaning for the 2 million slaves brought from Africa to Jamaica and Barbados. The slaves were cruelly used and were forbidden to speak their own languages or practice their own customs. Discipline was harsh, but the slave owners could never quite quell the spirit of rebellion that existed. Jamaica has a long history of slave uprisings and of slave violence against tyrannical planters.

For the slaves, there was also the ever-present inspiration of the Maroons, descendants of escaped slaves from Spanish days. Called cimarrones (runaways) by the Spaniards, these men and women lived in the mountains, defying and outwitting British troops at every turn. The Maroons drew other runaways and staged rebellions until a treaty in 1739 gave them a measure of autonomy that they retain to this day.

As it turns out, the planters proved almost as rebellious as their slaves. When the thirteen American colonies declared their independence from Britain, the Jamaica House of Assembly voted to join them. This declaration never quite took hold in world politics, but it was considered a daring gesture all the same. As with cotton in the American South, the entire sugar system proved less profitable when the slave trade was abolished in Jamaica in 1807 and slavery itself ended in 1838. The transition was peaceful compared to the Civil War that divided the United States. The planters’ initial plan was to hire former slaves who knew how to handle each job. But the English quickly discovered that most free men wanted nothing more to do with plantations. So a frenzied effort was launched to attract cheap labor from abroad, initiating Jamaica’s great age of immigration.

Workers came in ethnic waves over the decades. As each group rose from the lowest levels of the social system, another group had to be solicited to do the island’s dirty work. Small numbers of Germans and Irish came first, then workers from India and China followed in great numbers.

Schoolgirls during recess in Port Antonio. While these children may look relaxed, the education system in Jamaica is very competitive, with children having to take mandatory placement exams to win spots in schools, because there are not enough places for all the children.

A full 95 percent of Jamaica’s people trace their heritage to Africa, yet most have some link or distant relative tying them to Great Britain, the Middle East, China, Portugal, Germany, South America or another island in the Caribbean. In general, these groups live together peacefully—partially because they’ve had to over the years to survive and partially because there has been so much intermarriage.

By the mid 1900s, a “national identity” had supplanted a British one in the hearts and minds of Jamaicans. This new identity was given official recognition on August 6, 1962, when Jamaica became an independent nation with only loose ties to the Commonwealth. On that day, the Union Jack was lowered for the last time, and the new black, green and gold Jamaican flag was lifted up.

“Out of Many, One Nation” is the motto of Jamaica, though it struggles today with the same problems that plague so many Caribbean islands. Its unity can be heard in the language of its people, which carries both words and word patterns from West African languages. And when Jamaicans speak, even in dark moments, it is with a unique lilt that makes every sentence a song.

The Rastafarians

Reggae’s hypnotic beat carries Rasta’s message of protest and purity

By Norma Benghiat

The tremendous mingling of cultures in Jamaica has also led to a mingling of religions. The vast majority of Jamaicans consider themselves Christian, yet there are significant communities of Jews, Hindus, Moslems and other religions. But Rastafarianism is the religion that was born in Jamaica, and it commands a serious following on the island— along with the respect of even those Jamaicans who choose not to follow it.

Say the word “Rasta” and an image of marijuana-smoking reggae musicians comes to mind, for reggae is the most well known product of this religion, spread through the world as it has been by such famous reggae musicians as Bob Marley, who closely associated reggae with Rastafarianism.

The Rastafarian religion or movement is one of the most significant phenomenons to emerge out of Jamaica’s plantation slave society. It was born out of the need to counteract the denigration of people of African descent in a society that gave little recognition to the majority of its citizens. The Rastafarians withdrew from “Babylon” or Western society and created their own music, speech, beliefs, cooking, lifestyle, and attire.

The bright colors of these knit hats at a stand outside Ocho Rios incorporate the red and gold of the Ethiopian flag and reflect the tie that many Jamaicans feel to Africa.

Rastas believe in the deity of the late Ethiopian king, Haile Selassie, who is the messiah, Rastafari. They believe in repatriation to Ethiopia and consider themselves to be one of the tribes of Israel. Rastafarians believe that certain Old Testament chapters speak about Haile Selassie and Ethiopia. “Jah,” or God, is seen as a black man. The Rastas see themselves as the true Hebrews, chosen by “Jah.” Right-living Rastas are considered to be saints, and the others are called “brethren.”

The Rastafarian religion has a code against greed, dishonesty, and exploitation. Except for the sacramental smoking of ganja (marijuana, the possession, sale and use of which are illegal in Jamaica), true Rastas are law-abiding, have strong pride in black history, a positive self-image, and strive for self-sufficiency. The Rasta lifestyle reflects these beliefs.

Some of the orthodox Rastas resemble biblical figures, bearded and garbed in long robes, carrying staffs and covering their dreadlocks in turbans. Rastas quote Leviticus 21.5: “They shall not make baldness upon their head, neither shall they shave off the corners of their beard, nor make any cuttings in their flesh” as the reason for wearing dreadlocks, which are formed by leaving hair to grow naturally without combing. The longer the dreadlocks, the longer the Rasta’s devotion to the holy ways of living. Many Rastas wear dreadlocks wrapped neatly in turbans, and this is the only outward sign of their religion. They incorporate the colors of the Ethiopian flag, red, green and gold, into all kinds of clothing.

The Rastas’ diet, called I-tal (which means “natural” in the Rasta language), is essentially a strict vegetarian one. They believe that man should eat only that which grows from the soil. Food should not include the dead flesh of any living animal, and pork is strictly omitted. This diet also excludes manufactured food of any kind because it contains additives, which Rastas believe cause illnesses, such as cancer. In addition, the foods they eat are grown naturally, without the use of any artificial fertilizers.

I-tal cooking uses the produce of the land—peas, beans and a variety of other vegetables, starches and fruits that are locally available. While some Rastas will eat fish, chicken and I-tal food, others will eat only I-tal food in its raw state. Ganja is often included in cooked foods, and infusions are taken for medicinal purposes. Rastas abstain from hard liquor, beer and wine. Instead they drink fruit juices that are mixed to create nonalcoholic I-tal drinks.

Some Rastas do not use silverware or plates. Instead, they eat from coconut-shell bowls and calabash bowls with their fingers. This, they say, identifies them with their African roots. Some Rastas go so far as to refuse to drink processed water and instead collect rain water to use in the preparation of their food.

“Groundlings,” or gatherings, are held at specific times to celebrate the birthday of Haile Selassie or the Ethiopian Christmas and New Year. At these gatherings the niyabinga drums and Rastafarian music create an intense spiritual mood.

Ganja, which most likely came to Jamaica with the East Indians, plays an important role in the lives of the Rastas. Ganja is smoked in cone-shaped “spliffs” made from brown paper bags or newspaper, or in a bamboo chillum pipe that is passed around by members. The Rastas smoke the herb to inspire open conversation.

The Rastas have developed their own dialect by replacing the “me” in the Jamaican Creole language with “I and I,” in order to insert a positive notion of self into their speech. For example, “me have mi table” is changed to “I and I have mi table.”

Vibrant colors are the hallmark of Rastafarian art, and its influence can be seen in the works of traditional artists such as Parboosingh, as well as in ceramics, the theater and dance. The profound influence the Rastas have had on indigenous musical forms is well known, from ska to rock steady to the most significant phenomenon, reggae. The latter, with its hypnotic beat and protest lyrics, has created an artistic form that has taken on a life of its own and carried the spirit of Rastafarianism throughout the world.

From the Field to the Table

Exotic fruits and vegetables of every color and shape find their way into Jamaican cuisine

By Norma Benghiat

It might have been the climate and fertility that first brought the Amerindians to Jamaica, but it was the search for gold that brought the Europeans. When this search failed, they turned to the island’s other resources. There are crops that were brought to Jamaica from far away that have flourished here as in no other place.

In the days of the great plantations, many slaves were allowed to grow their own vegetables in tiny plots around their huts— though animal husbandry was, for the most part, forbidden them. There was a superstition that slaves allowed to eat red meat would develop a taste for their masters. Small-time agriculture, however, prospered in this way, producing a surplus the slaves were encouraged to sell among themselves. This produced the Jamaican tradition of Sunday as market day—a swirling scene in the center of a town, the air alive with shouts of higglers (street vendors) hawking their wares.

Jamaican markets were the social gathering place for the country folk to meet to gossip and exchange news. Both the buyers and the sellers came together to partake in this weekly event, which could be likened to a country fair.

On her way to the market near Port Antonio, this woman has stopped to show us her freshly picked mangoes. The traditional way to carry a bundle is on one’s head.

In those days, the country folk would set out very early in the morning, or often the day before, with their donkeys laden with produce. Drays drawn by mules would create a mighty traffic jam as they weaved through the throng of people.

Inside and outside the market there would be an abundance of colorful fresh fruits and vegetables—red tomatoes, mangoes and pawpaws; purple eggplants; a green abundance of chochos and callaloo; bunches of green and ripe bananas, breadfruits and plantains—all arranged to catch the eye of the passerby.

Part of the noise and bustle were the loud cries of the higglers, who, as Martha Beckwith wrote in Black Roadways, “had their own musical cry which rises and falls with a peculiar inflection.

“‘Buy yu’ white yam!, Buy yu’ yellow yam!, Buy yu’ green bananas!’

“‘Ripe pear fe breakfast—ripe pear!’”

Peddlers or higglers, like the one pictured, are usually female, a tradition that has predominated since it was brought over from West Africa during the colonial period.

Not many itinerant vendors are to be found in towns today. The higglers have established themselves in market stalls and now often sell on the roadsides, asking prices that are higher than those in the supermarket. The produce they carry, however, is usually of superior quality.

Today’s markets have changed with the times; very rarely are donkeys and carts used for transportation. The market people now arrive via bus, track or van. There are rarely live chickens for sale. Markets are not as vibrant as they were in the presupermarket days, but the market is still the place to find the widest selection of fresh produce.

Much of the vegetables and fruits in Jamaica are grown by small farmers. There are very few large fruit orchards. Instead small farmers mix their fruit trees with vegetables so that the standard Jamaican backyard is thickly planted with mangoes, limes, sweet and sour sops, ackees, sugar cane, bananas, avocados and whatever else the land will hold.

Vegetables are grown both in the cooler mountains and on the plains. The Santa Cruz area of St. Elizabeth is known as the breadbasket of Jamaica. The industrious farmers here manage to produce an abundance of food, in spite of a lack of irrigation, through heavy mulching, which helps the soil retain moisture. The largest quantities of scallions, thyme and onions are grown in this area. The mountain regions produce excellent lettuce, bok choy, cabbage, scallions and thyme.

Starches and root crops consisting of breadfruit, cassava (bitter and sweet), sweet and Irish potatoes, cocos, yams, plantains and bananas both ripe and green—the latter being eaten as a starch—are grown both in the mountains and on the plains.

The island is blessed with an astonishing variety of fruits—some indigenous, others introduced over the centuries. Summer is, of course, the most abundant season for fruits such as pineapples, mangoes, otaheiti apples, sweet and sour sops, plums, naseberries and so on.

Both dairy and beef cattle are raised in Jamaica. Beef cattle were usually bred by owners of large sugar estates and other landowners who had enough acreage of pangola grass to support the cattle. Pigs were introduced into Jamaica as early as the sixteenth century by the Spaniards and became wild in the mountains. They were notably hunted and barbecued, or “jerked,” by the Maroons, using a method that was uniquely their own. Originally, goats were reared by the peasantry strictly for their milk. However, with the influx of Indian immigrants, the demand for goat meat has escalated to such an extent that this meat is often more expensive than beef. Poultry was introduced in waves to the island by the Spaniards, the English, and the Africans. Many households also raise chickens on a small scale.

Fish and crustaceans were once abundant but have become scarce owing to overfishing. They now come mainly from the Pedro Banks to the south of the island, and commercially produced pond fish now fill the demand for wild fish.

The astonishing array of ingredients available on the island has been the source of inspiration for many a newcomer to Jamaica, who, eager to recreate recipes from home, has created new dishes that are at the root of today’s Jamaican cuisine.

Eating and Cooking

Goat feeds and wedding cakes—new traditions displace the old

By Norma Benghiat

Jamaica’s cuisine has changed over time, and new traditions have displaced some of the old. But eating customs and dishes exist there today that are both remnants of Jamaica’s colonial history and the result of its many immigrant contributions.

One cannot say enough about the influence of immigration on the food of Jamaica. Since the English had already acquired a craving for curry in India, Indians found a ready audience for their contributions to the great Jamaican cook pot. They brought from home the technique for blending fragrant curry powders and using them to showcase local meat and fish. When traditional lamb proved hard to find, they drafted the most convenient substitute. The dish curried goat was born, turning up now and again with a side of chow mein.

The Chinese and, in smaller numbers, the Syrians and Lebanese added tremendous complexity to Jamaica’s culture and cuisine. The island’s very old Jewish community was joined over time by migrant Arab traders from Palestine. These groups all prepared traditional dishes from their homes—curried goat and sweet and sour pork, to name a few of the many—that have become an integral part of Jamaica’s cuisine.

Plantains, which like bananas were brought to the island by the Spanish, are eaten by the locals in a variety of ways—green or ripe, salty or sweet, fried, baked or boiled. This stuffed plantain is one of the best variations.

Eating traditions hark back to the days of Britain’s control of the island. During the eighteenth century on the plantations meals were copious for the residents of the grand plantation houses. The day began with a cup of coffee, chocolate or an infusion of some local herb, all equally called “tea.” Breakfast was served later in the morning, a “second breakfast” was served at noon, and dinner was served in the late afternoon or evening. Both the breakfast and “second breakfast” were substantial meals, as was dinner.

Today’s Jamaican breakfast varies considerably depending on where one lives. Farmers, who rise early to tend their fields, start the day with a cup of “tea.” Late in the morning they may eat a substantial breakfast of callaloo and saltfish (salted cod), ackee and saltfish accompanied with yams, roasted breadfruit, dumplings or green bananas.

This festive Jamaican dinner brings together the Caribbean flavors of pineapple and pork.

Both country and town lunches consist of some of the favorite Jamaican dishes, such as stewed peas (which are what Jamaicans call beans); curried goat; oxtail; escoveitched fish (marinated in lime juice), brown stewed fish (pan-fried and then braised in a brown sauce seasoned with hot peppers and spices) or simply fried fish. These main dishes are usually served with rice, yams, green bananas or other starches. There might also be a satisfying soup of meats, vegetables, yams, cocos (taro, also called dasheen) and dumplings served as a one-pot meal. Dinner can include stewed beef, jerked meat, oxtail and beans, fish or fricasseed chicken.

The most important meal of every Jamaican household is the traditional Sunday dinner. This is usually eaten midafternoon after eating a bigger Sunday breakfast of ackee and saltfish or liver and onions with johnny cakes, green bananas and bammie (a flat cassava bread) and fruit.

Dinner (sometimes called late lunch as well) is the time when family and friends gather for a more relaxed meal. Rice and peas are de rigueur for Sundays, and often at least two meats—fricasseed chicken as well as a very spicy roast beef—will be served. Fried plantains, string beans, carrots and a salad might accompany the meats, followed by a pudding, cake or fruit salad. Beverages include soft drinks, lemonade, coconut water, beers and rum or rum punch.

Christmas is the most important holiday of the year for Jamaicans. This goes back to the days of slavery when there were four seasonal holidays— Christmas, Easter or Picanny Christmas, Crop over Harvest and the Yam Festival. The Yam Festival has since disappeared, but the other three holidays are still celebrated, and celebrated well.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Christmas consisted of three nonconsecutive days— Christmas, Boxing and New Year’s Days. During this time, a temporary metamorphosis occurred in the relationship between master and slaves: the slaves assumed names of prominent whites, richly dressed (most of their savings went into dressing), and addressed their masters as equals. Christmas celebrations began early in the morning when a chorus of slaves visited the great house, singing “good morning to your nightcap and health to the master and mistress.” After this, the slaves collected extra rations of salted meats for the three days of celebrations.

The great attraction on Boxing Day was the John Canoe Dance—which is slowly dying out—and on New Year’s Day, the great procession of the Blue and Red Set Girls. Each set gave a ball, and each was represented by a king and queen. The queen and her attendants wore lavish gowns that were kept secret until the day of their appearance.

For most Jamaicans today, the idea of Christmas conjures up cool days, shopping, social gatherings, and much eating and drinking. This is the time of year when the sorrel plant, used to make the traditional red Christmas drink, is in season along with the fresh gungo (pigeon) peas used to make Christmas rice and peas. A very rich plum pudding, made from dried fruits soaked for weeks in rum and port, is a must for Christmas dinner. It is usually served with a “hard” or brandy sauce.

Easter time reflects the passing of the cooler months and heralds the coming of summer. For strict Catholics, it means the abandoning of meats for fish. Even though the majority of the Jamaican population is not Catholic, more fish is eaten during Lent than at any other time of the year.

The eating of bun and cheese during Easter is a truly Jamaican innovation. Buns of every description are baked and eaten in large quantities—especially as a snack with a piece of cheese. Each bakery vies with the next to produce the best buns. But the buns of yesteryear, most of which were baked by small bakeries, were much tastier than today’s. Now the large bakeries make most of the buns, and at times the raisins and currants are hardly visible except as decorations.

Jamaican weddings today have become much like those in the United States. But of more interest were the old country weddings, celebrated grandly and often attended by the whole village. They were preceded by many nights of preparation, usually consisting of ring games. A feed was held the night before the wedding for the groom. This consisted of curried ram goat and sometimes “dip and fall back,” a dish of salted shad cooked in coconut milk and served with a lot of rum. It is said that the goat’s testicles were roasted and served to the groom. These days, mannish water, a stew made of a goat’s organs and head is served to grooms the night before the wedding to increase virility.

The day before the wedding a procession of young girls, all dressed in white, carried the wedding cakes on their heads to the bride’s house. The main cakes were in the form of pyramids, and each cake was covered with a white veil. The picturesque custom of young girls carrying the cakes on their heads has almost disappeared as transportation by cars is now used more often.

The wedding feast differed from village to village, but usually it consisted of a huge meal of roast pig, curried goat and traditional side dishes. The Sunday following the celebrations, the couple attended church with members of the wedding party.

While these traditions are slipping away, the flavors of the past are alive and well in Jamaica.

The Joys of Jerk

The island’s fiery food fetish has become a global addiction

Jerk—the fiery food that is now popular throughout the globe—is truly a part of Jamaica’s history. From M.G. Lewis in 1834 to Zora Neale Hurston in 1939, chroniclers of the West Indies tell us of their flavorful encounters with the Maroons—and even with the Maroons’ favorite food, a spice and pepper-encrusted slow-smoked pork called “jerk.” The Maroons, escaped slaves living in Jamaica’s jungle interior, developed many survival techniques—but none more impressive than the way they hunted wild pigs, cleaned them between run-ins with the law, covered them with a mysterious spice paste and cooked them over an aromatic wood fire.

Lewis gives us a vivid picture of a Maroon dinner of land tortoise and barbecued pig: “two of the best and richest dishes that I ever tasted, the latter in particular, which was dressed in the true Maroon fashion being placed on a barbecue, through whose interstices the steam can ascend, filled with peppers and spices of the highest flavor, wrapped in plantain leaves and then buried in a hole filled with hot stones by whose vapor it is baked, no particle of juice being thus suffered to evaporate.”

A cook serves up jerk at Faiths Pen—a lively collection of fastfood stalls along the highway that crosses the island between Ocho Rios and Kingston.

Even more exciting is Hurston’s description a century later of an actual hunting expedition with the Maroons. As an anthropologist, she was trained to discern cultural and ethnic truths. But in one extended passage, what she discovers is the unforgettable flavor of jerk pork.

“All of the bones were removed, seasoned and dried over the fire to cook. Towards morning we ate our fill of jerked pork. It is more delicious than our American barbecue. It is hard to imagine anything better than pork the way the Maroons jerk it. When we had eaten all that we could, the rest was packed up with the bones and we started the long trek back to Accompong.”

Thanks to Americans who have followed in Hurston’s footsteps, the jerk-scented “trek back to Accompong” has never ended. The Maroon method of cooking and preserving pork has become a Jamaican national treasure, inspiring commercial spice mixes, bottled marinades and the use of the word “jerk” around the world.

The word “jerk” itself, as with so many in Jamaica, is something of a mystery. Most Jamaicans offer the non-scholarly explanation that the word refers to the jerking motion either in turning the meat over the coals or in chopping off hunks for customers. Still, there is a more serious explanation.

“Jerk,” writes F. G. Cassidy (who penned the Dictionary of Jamaican English published in London in 1961), “is the English form of a Spanish word of Indian origin.” This process of linguistic absorption is so common in the Caribbean that it is persuasive here. Cassidy says that the original Indian word meant to prepare pork in the manner of the Quichua Indians of South America. Thus, jerking was learned from the Indians, either the Arawaks or others from across the Caribbean, and preserved by the Maroons. There’s also an undeniable link to the Dutch word gherken, meaning “to pickle or marinate.”

Until recently, jerk remained a dish made with pork, true to its roots. Now roadside pits and “jerk centers” dish up chicken, fish, shrimp—even lobster. Until recently, jerk was found only in parts of Jamaica with strong Maroon traditions, including the interior known as Cockpit Country and a tiny slice of Portland on the northeast coast at Boston Bay. Now jerk is sold everywhere, and its irresistible scent, which impressed Lewis and Hurston in their day, fills the air.

At this jerk stand in Port Antonio, near the mecca of jerk, Boston Bay, chicken is cooked over coals made from burning wood and pimento (allspice) branches. Jamaicans short on space often saw oil drums in half and build a fire on the bottom of the drum while cooking the meat on a grill above it.

Several of the best jerk purveyors are still on the beach at Boston Bay, somewhat off the tourist track and therefore frequented by Jamaicans. These eateries are little more than thatch-roofed huts built over low-lying, smoldering fires. On top of these fires you’ll often find sheets of tin, blown off some roof in a storm, that are used as griddles. The meat is cooked on these sheets, covered with plantain leaves.