Читать книгу L'Americain - John Launois - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

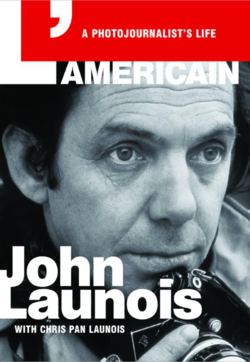

Civilian CIVILIAN VACUUM CLEANER SALES MAN, GAS STATION ATTENDANT SAN FERNANDO VALLEY, CA 1955

ОглавлениеDuring two years of active duty, I managed to buy a used Rolleiflex camera and new Leica, I had seen a new country, and had fallen in love. In a way, things were looking up. Yet it felt like time was running out: I was 26 and had no paying job in sight. I thought I’d better manage my anxiety quickly and get into action.

With another ex-soldier heading south, I walked out of Fort Ord. At a used car lot, my friend helped me find a car. We checked several vehicles by putting our fingers in the transmission to detect sawdust in the gears, as some dealers softened the noise of a bad transmission by filling it with sawdust. We also gunned accelerator pedals to the floor for several seconds to see if engines knocked and smoked.

For $50, I settled on a gray four-door 1940 Dodge, once probably white, and my friend shared the cost of gas to Santa Barbara. After dropping him off, I headed straight for the San Fernando Valley and drove to a cheap motel. Remembering the cherry pies I loved, I found a restaurant and had two helpings to cheer myself up. I was a civilian again. Accustomed to the Army’s free room and board, it took a while to adjust to my new freedom.

Looking for a job, I visited Major Douglas Parker at the 146th Fighter Group Air National Guard in Van Nuys. Always a generous man, he said, “Though your photo job was taken while you were away, there’s an opening in base operations.” I took the job immediately and started working from 5:00 p.m. to midnight as a flight planner, helping pilots with all weather, takeoff, and landing information needed for flights.

To earn enough for a trip to the east coast and the $400 boat fare to Japan, I needed more than one job. After looking around, I was hired as a Texaco gas station attendant and worked from six in the morning till noon. Then I noticed a want-ad for a door-to-door vacuum cleaner salesman; I applied and began working from noon till 4:30 in the afternoon.

Selling vacuum cleaners door-to-door was the hardest job I ever had, as it meant selling people machines they did not necessarily need. Though I hated to recite the virtues of my vacuum cleaners, I sold four machines in my first week. My manager was so impressed, he asked me to give a speech to his regular salesmen. He told me to “explain your methods to them,” but I had no methods. Perhaps I sold more because customers sensed I was not a salesman, and they felt sorry for me.

An executive from a major Hollywood studio bought two vacuum cleaners, one for his home and one for his summer house. He and his wife thought I was a student, but when I told them I was a photographer, he offered me a job as set photographer. I thanked him but explained my calling was strictly photojournalism.

Not all attempts at sales went so well. Our vacuums had a device to shampoo carpet, which often helped close a sale. On one occasion, as I demonstrated this feature, shampooing a stain on a worn-out Persian carpet, the polisher slowly dug a hole in the carpet before I could stop it. My potential customers looked at me in horror.

Holding three jobs meant I didn’t sleep much. I led a frugal life, saving as much as possible for New York and Japan.

Around that time, I came upon a Department of Defense ruling that allowed a reservist to transfer to another branch of service if an individual’s service was requested, so I asked Major Parker if he could help me transfer from the U.S. Army Reserve to the Air Force Reserve. I always loved being around planes, and since I had a five-year obligation to the Army Reserve, I thought if recalled, I’d rather be in the Air Force Reserve.

Major Parker made the request and I was transferred. To my surprise, I discovered my new status offered an unusual opportunity to reach New York in the copilot’s seat of F-80s flying on training missions.

All dispatchers, aware I wanted to go to New York, would inform me as soon as they knew of a two-seater fighter plane with a single pilot who could fly me to the east coast. I wrote Kurt Kornfeld at Black Star about my plans to show him, Ernest Mayer, and Howard Chapnick my two essays on Japan, and Kurt let me know they looked forward to seeing me again after nearly five years.

While waiting to hear of an available flight, I wrote to Keiko on weekends and would rest at every opportunity. With three jobs on weekdays, I slept an average of four hours a night.